Maine Law Review Tilt

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Doyle F. Brunson (Conceived September 9, 1933) Is a US Registered Poker Musician That Tried Properly for Longer Than Fifty Years

Doyle F. Brunson (conceived September 9, 1933) is a US registered poker musician that tried properly for longer than fifty years. She's a two-time Wsop Top Level winner, a Gaming Hall of Fame member, along with author of numerous magazines on gaming. SEC investigation Brunson is pair On-line poker fists called after him. One pay, a 8 and a a couple of any fit, needs his name while he snagged the No Reduce Harbor 'Em time over the Economy Series of Poker a couple of years one after with them (1976 and 1977), in the two caser making a a stuffed house. Inside 1976 and 1977, he had been an underdog the actual final <Blank>. Another pay known as the "Doyle Brunson," specifically in Tx, are the star and princess of every businessman since, because he affirms on page 519 of Super/System, he "rarely works this arm." He changes his phrasing in Super/System 2, still, remembering that she "efforts to rarely meet this handheld." Hamilton moved to City, when the rest teamed up and traveled around completely, wagering on gaming, golf and, in Doyle's term, "pretty much everything." They pooled their for wagering and after four decades, they made their earliest important visit to City and puzzled everyone of it, a six- figure extent. They thought I would stop being as couples though remain friends. Now well into his time of life, Brunson is just as populated <Blank> ever and, by his money, even earning additional than he squanders. From humble root to just one pretty important drives in gambling proper, Brunson means it when he claims, "A dude with funds are no match against a man for a journey." Brunson had begun playing gaming before his problem, performing five-card change and uncovering it "effective." He played further often Since we have been hurt with his profits invite his payments. -

03/26/04 Chip / Token Tracking Time: 04:45 PM Sorted by City - Approved Chips

Date: 03/26/04 Chip / Token Tracking Time: 04:45 PM Sorted by City - Approved Chips Licensee ----- Sample ----- Chip/ City Approved Disapv'd Token Denom. Description LONGSTREET INN & CASINO 09/21/95 00/00/00 CHIP 5.00 OLD MAN WITH HAT AND CANE. AMARGOSA LONGSTREET INN & CASINO 09/21/95 00/00/00 CHIP 25.00 AMARGOSA OPERA HOUSE AMARGOSA LONGSTREET INN & CASINO 09/21/95 00/00/00 CHIP 100.00 TONOPAM AND TIDEWATER CO. AMARGOSA LONGSTREET INN & CASINO 01/12/96 00/00/00 TOKEN 1.00 JACK LONGSTREET AMARGOSA LONGSTREET INN & CASINO 06/19/97 00/00/00 CHIP NCV, HOT STAMP, 3 COLORS AMARGOSA AMARGOSA VALLEY BAR 11/22/95 00/00/00 TOKEN 1.00 GATEWAY TO DEATH VALLEY AMARGOSA VALLEY STATELINE SALOON 06/18/96 00/00/00 CHIP 5.00 JULY 4, 1996! AMARGOSA VALLEY STATELINE SALOON 06/18/96 00/00/00 CHIP 5.00 HALLOWEEN 1996! AMARGOSA VALLEY STATELINE SALOON 06/18/96 00/00/00 CHIP 5.00 THANKSGIVING 1996! AMARGOSA VALLEY STATELINE SALOON 06/18/96 00/00/00 CHIP 5.00 MERRY CHRISTMAS 1996! AMARGOSA VALLEY STATELINE SALOON 06/18/96 00/00/00 CHIP 5.00 HAPPY NEW YEARS 1997! AMARGOSA VALLEY STATELINE SALOON 06/18/96 00/00/00 CHIP 5.00 HAPPY EASTER 1997! AMARGOSA VALLEY STATELINE SALOON 06/21/96 00/00/00 CHIP 0.25 DORIS JACKSON, FIRST WOMAN OF GAMING AMARGOSA VALLEY STATELINE SALOON 06/21/96 00/00/00 CHIP 0.50 DORIS JACKSON, FIRST WOMAN OF GAMING AMARGOSA VALLEY STATELINE SALOON 06/21/96 00/00/00 CHIP 1.00 DORIS JACKSON, FIRST WOMAN OF GAMING AMARGOSA VALLEY STATELINE SALOON 06/21/96 00/00/00 CHIP 2.50 DORIS JACKSON, FIRST WOMAN OF GAMING AMARGOSA VALLEY STATELINE SALOON -

Longtime Gaming Executive Bobby Baldwin to Leave MGM Resorts International

NEWS RELEASE Longtime Gaming Executive Bobby Baldwin To Leave MGM Resorts International 10/4/2018 LAS VEGAS, Oct. 4, 2018 /PRNewswire/ -- MGM Resorts International (NYSE: MGM) ("MGM Resorts") today announced that Robert Baldwin, Chief Customer Development Officer of MGM Resorts and CEO and President of CityCenter, will be leaving his positions at both companies later this year. Few have played a more central role in the growth and transformation of the gaming industry than Bobby, and his contributions over more than three decades are immeasurable. MGM Resorts thanks Bobby for all he has done for the company and all he has meant to this industry and wishes him the best for the future. ABOUT MGM RESORTS INTERNATIONAL MGM Resorts International (NYSE: MGM) is an S&P 500® global entertainment company with national and international locations featuring best-in-class hotels and casinos, state-of-the-art meetings and conference spaces, incredible live and theatrical entertainment experiences, and an extensive array of restaurant, nightlife and retail offerings. MGM Resorts creates immersive, iconic experiences through its suite of Las Vegas-inspired brands. The MGM Resorts portfolio encompasses 28 unique hotel offerings including some of the most recognizable resort brands in the industry. Expanding throughout the U.S. and around the world, the company in 2018 opened MGM Springfield in Massachusetts, MGM COTAI in Macau, and the first Bellagio-branded hotel in Shanghai. The 81,000 global employees of MGM Resorts are proud of their company for being recognized as one of FORTUNE® Magazine's World's Most Admired Companies®. For more information visit us at www.mgmresorts.com. -

In Business Q and A

In Business Q and A Jim Murren, President and COO of MGM Mirage Interviewed by Richard Velotta / Staff Writer Jim Murren's promotion to president and chief operating officer of MGM Mirage didn't get much attention when it occurred last summer. That's because, at the time, the company was in the midst of so much other news that overshadowed the announcement: A deal with Dubai World that places half of the ownership of Project CityCenter in the hands of a foreign investor; another with Sol Kerzner, whose spectacular Atlantis project in the Bahamas is considered one of the premier resorts in the world, to design a Jim Murren is president and project with MGM Mirage on a site at Las Vegas Boulevard and chief operating officer of MGM Sahara Avenue; and the opening of a new casino resort in Mirage. Detroit. Photo by Steve Marcus And Murren, who joined the company in 1998, has been involved in all of them. He started with the company as executive vice president and chief financial officer after a 14-year Wall Street career. In 1999, he was named president and chief financial officer, and he is a member of MGM Mirage's board of directors and its executive committee. A strong believer in philanthropy, Murren and his wife, Heather, founded the Nevada Cancer Institute, a nonprofit institution dedicated to providing a cancer center for the state. He also serves as a trustee for foundations at the University of Nevada, Reno, and UNLV. Murren talked with In Business Las Vegas about several of his company's recent deals, progress at CityCenter and why he's frustrated with some of the community's problems — and the people who feel gaming taxes should be raised to solve them. -

Media Guide World Series of Poker Main Event Final Table November 10-11, 2014

*JACOBSON*LARRABE*NEWHOUSE*PAPPACONSTANTINOU*POLITANO*SINDELAR*STEPHENSEN*TONKING*VAN HOOF* Media Guide World Series of Poker Main Event Final Table November 10-11, 2014 Live on ESPN2 at 5 pm PT Monday Live on ESPN at 6 pm PT Tuesday Penn & Teller Theater Rio® All-Suite Hotel & Casino *JACOBSON*LARRABE*NEWHOUSE*PAPPACONSTANTINOU*POLITANO*SINDELAR*STEPHENSEN*TONKING*VAN HOOF* 1 2014 WSOP NOVEMBER NINE Media Guide Documents: Cover Page……………………………………………………………………………………………………1 Table of Contents……………………………………………………………………………………………..2 Important Notes for Media……………………………………………………………………………………3 FINAL TABLE INFORMATION Where We Are and Where We Left Off……………………………………………………………………….4 Schedule of Events……………………………………………………………………………………………5-6 Final Table Odds Sheet………………………………………………………………………………………..7 Final Table Fact Sheet…………………………………………………………………………………………8 ESPN TV Schedule……………………………………………………………………………………………9 November Nine Chip Counts by Day…………………………………………………………………………10 Final Table Seating Chart……………………………………………………………………………………...11 Updated Payouts………………………………………………………………………………………………12 All You Need is a Chip and a Pair……………………………………………………………………………..13 MEET THE NOVEMBER NINE Seat 1: Billy Pappaconstantinou………………………………………………………………………………..14 Seat 2: Felix Stephensen……………………………………………………………………………………......15 Seat 3: Jorryt van Hoof…………………………………………………………………………………………16 Seat 4: Mark Newhouse………………………………………………………………………………………...17 Seat 5: Andoni Larrabe………………………………………………………………………………………....18 Seat 6: William Tonking………………………………………………………………………………………..19 Seat 7: Dan -

Deposit Bonuses to Get Started

DEPOSIT BONUSES TO GET STARTED FullTiltPoker (100% Deposit Bonus up to $600) Play Online Poker CakePoker (110% Deposit Bonus up to $600) WilliamHill (100% Deposit Bonus & $120,000 RakeRace) PrestigeCasino ($1,500 in FREE Spins No Deposit Needed) PokerStrategy ($50usd Starting Capital FREE No Deposit Needed) WilliamHill Bingo ($40usd FREE To Start Playing No Deposit Required) 1 Play poker online at Doyles Poker Room TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE • For eward 3 • Pr eface 6 • I ntroduction 8 • M y Story 12 • T he History of No Limit 37 • O nline Poker 46 • E xclusive Super/System 2 66 • Speci alize or learn 101 • L imit Hold'em Poker 130 • O maha Eight or Better 164 • Seven Card Stud High Low 223 • Pot Limit Omaha High 262 • T riple Draw Poker 296 • T ournament Overview 331 • N o Limit Hold'em 336 • Wor ld Poker Tour 430 • Poker Glossary 241 2 FOREWORD by Avery Cardoza Super/System 2 gathers together the greatest poker players and theoreticians today. This book is not meant to replace the original Super/System, but to be an extension of that great work, with more games, new authors, and most importantly, more professional secrets from the best in the business. Doyle’s expert collaborators have won millions upon millions of dollars in cash games—that’s each one of them. You’ll be learning expert strategies from a pool of talent that includes three world champions—Doyle Brunson, Bobby Baldwin, and Johnny Chan (Doyle and Johnny being two-time consecutive winners). Add to that an all-star team of contributors with so many World Series of Poker bracelets among them, you could fill a bucket with their gold. -

Championship No-Limit & Pot-Limit Hold'em (On the the Road to The

Championship No-Limit & Pot-Limit Hold'em (On the the Road to the World Series of Poker) by T.J. Cloutier and Tom McEvoy Copyright 1997 by T.J. Cloutier, Tom McEvoy and Dana Smith All rights reserved First printing: 1997 Second printing: 1999 Third printing: 2001 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 97-67348 ISBN 1884466311 Editorial Consultant: Dana Smith Cover Design: Jo Vogelsang Cover Photo of T.J. Cloutier at the 1996 World Series of Poker courtesy of Larry Grossman, author of You Can Bet On It! Title page photo: T.J. Cloutier and Tom McEvoy, winner and runner-up at Foxwoods Casino pot-limit hold'em tournament Cardsmith Publishing 4535 W.Sahara #105 Las Vegas, NV 89102 www.poker books, com TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword, by Mansour Matloubi................................4 World Series of Poker Champion, 1990 Introduction, by Tom McEvoy....................................7 World Series of Poker Champion, 1983 A Conversation with T. J., by Dana Smith.................9 Chapter One Getting to Know Your Opponents......................... 28 Chapter Two Pot-Limit Hold'em Strategy................................. 40 Chapter Three How to Win Pot-Limit Hold'em Tournaments....... 84 Chapter Four How to Win No-Limit Hold'em Tournaments...... 104 Chapter Five No-Limit Hold'em Practice Hands.......................172 Chapter Six Tales From T. J................................................... 194 Cardsmith Publishing........................................ 210 FOREWORD by Mansour Matloubi, 1990 Champion, World Series of Poker T. J. Cloutier and Tom McEvoy have written a book that is very much needed by poker players. They may be giving too much away in Championship No-Limit Hold'em and Pot- Limit Ho Id'em .. -

Moneymaker Effect the Inside Story of the Tournament That Forever Changed Poker

The Moneymaker Effect The Inside Story of the Tournament That Forever Changed Poker Eric Raskin HUNTINGTON PRESS Las Vegas, Nevada The Moneymaker Effect The Inside Story of the Tournament That Forever Changed Poker Published by Huntington Press 3665 Procyon Street Las Vegas, Nevada 89103 Phone: (702) 252-0655 email: [email protected] Copyright ©2014, Eric Raskin eBook ISBN: 978-1-935396-11-6 Print ISBN: 978-1-935396-56-7 Cover Design: Will Tims Production & Design: Laurie Cabot Portions of this book were originally published by Grantland.com and are used with permission. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be translated, repro- duced, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechani- cal, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without the express written permission of the copy- right owner. Contents Foreword ..................................................................................... 1 Introduction ............................................................................... 3 Cast of Characters...................................................................11 1. Buildup to the Boom .............................................................19 2. ESPN Antes Up .........................................................................35 3. The Chris Moneymaker Story .............................................63 4. Day One .....................................................................................77 5. Day Two .....................................................................................93 -

World Series of Poker (Wsop)

OFFICIAL MEDIA GUIDE 42nd ANNUAL WORLD SERIES OF POKER May 31 - July 19, 2011 Rio All-Suite Hotel & Casino, Las Vegas November Nine – November 5-7 www.WSOP.com 1 2011 Media Guide Documents: COVER PAGE ................................................................................................................................................................................................1 TABLE OF CONTENTS............................................................................................................................................................................. 2-3 WSOP COMMUNICATIONS TEAM ............................................................................................................................................................4 2011 WSOP INFORMATION: DAILY TIME SCHEDULE ...................................................................................................................................................................... 6-10 ABOUT THE WSOP.....................................................................................................................................................................................11 FACT SHEET – 2011 WSOP........................................................................................................................................................................12 2011 ESPN TV SCHEDULE.........................................................................................................................................................................13 -

GOING ALL-IN on the AMERICAN DREAM: MYTH, RHETORIC, and the POKERIZATION of AMERICA Aaron M

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Communication Studies Theses, Dissertations, and Communication Studies, Department of Student Research 4-20-2011 GOING ALL-IN ON THE AMERICAN DREAM: MYTH, RHETORIC, AND THE POKERIZATION OF AMERICA Aaron M. Duncan University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Duncan, Aaron M., "GOING ALL-IN ON THE AMERICAN DREAM: MYTH, RHETORIC, AND THE POKERIZATION OF AMERICA" (2011). Communication Studies Theses, Dissertations, and Student Research. Paper 8. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/commstuddiss/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Communication Studies, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Communication Studies Theses, Dissertations, and Student Research by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GOING ALL-IN ON THE AMERICAN DREAM: MYTH, RHETORIC, AND THE POKERIZATION OF AMERICA by Aaron Michael Duncan A DISSERTATION Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Major: Communication Studies Under the Supervision of Professor Ronald Lee Lincoln, Nebraska May, 2011 GOING ALL IN ON THE AMERICAN DREAM: REHTORIC, MYTH, AND THE POKERIZATION OF AMERICA Aaron Michael Duncan, Ph.D. University of Nebraska, 2011 Adviser: Ronald Lee This dissertation takes a rhetorical approach in exploring the rise of gambling in America, and in particular the growth of the game of poker, as a means to explore larger changes to America‘s collective consciousness. I argue that the collective American conscious has undergone dramatic changes in recent years and an increased acceptance of gambling is reflective of these changes. -

33 04 Web.Pdf

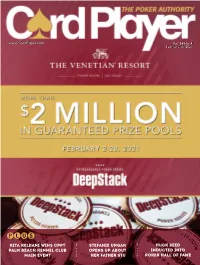

www.CardPlayer.com Vol. 34/No. 4 February 10, 2021 Rita Keldani Wins CPPT Stefanie Ungar Huck Seed Palm Beach Kennel Club Opens Up About Inducted Into Main Event Her Father Stu Poker Hall Of Fame PLAYER_35_4B_Cover.indd 1 1/21/21 8:09 AM PLAYER_04_GlobalPoker_DT.indd 2 1/19/21 10:54 AM PLAYER_04_GlobalPoker_DT.indd 3 1/19/21 10:54 AM Masthead - Card Player Vol. 34/No. 4 PUBLISHERS Barry Shulman | Jeff Shulman Editorial Corporate Office EDITORIAL DIRECTOR Julio Rodriguez 6940 O’Bannon Drive TOURNAMENT CONTENT MANAGER Erik Fast Las Vegas, Nevada 89117 ONLINE CONTENT MANAGER Steve Schult (702) 871-1720 Art [email protected] ART DIRECTOR Wendy McIntosh Subscriptions/Renewals 1-866-LVPOKER Website And Internet Services (1-866-587-6537) CHIEF TECHNOLOGY OFFICER Jaran Hardman PO Box 434 DATA COORDINATOR Morgan Young Congers, NY 10920-0434 Sales [email protected] ADVERTISING MANAGER Mary Hurbi Advertising Information NATIONAL SALES MANAGER Barbara Rogers [email protected] LAS VEGAS AND COLORADO SALES REPRESENTATIVE (702) 856-2206 Rich Korbin Distribution Information cardplayer Media LLC [email protected] CHAIRMAN AND CEO Barry Shulman PRESIDENT AND COO Jeff Shulman Results GENERAL COUNSEL Allyn Jaffrey Shulman [email protected] VP INTL. BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT Dominik Karelus CONTROLLER Mary Hurbi Schedules FACILITIES MANAGER Jody Ivener [email protected] Follow us www.facebook.com/cardplayer @CardPlayerMedia Card Player (ISSN 1089-2044) is published biweekly by Card Player Media LLC, 6940 O’Bannon Drive, Las Vegas, NV 89117. Annual subscriptions are $39.95 U.S. ($59.95 U.S. for two years), $59.95 Canada, and $75.95 International. -

Ebook Cowboys, Gamblers & Hustlers: the True Adventures of A

Ebook Cowboys, Gamblers & Hustlers: The True Adventures Of A Rodeo Champion & Poker Legend Freeware This inside looks at the early glory days of hold'em, playing in smoky backrooms with legends such as Titanic Thompson and Doyle Brunson. Get a look at vintage Las Vegas when Cowboy's friend, Benny Binion ruled Glitter Gulch and ride along with the road gamblers as they faded the white line from Dallas to Shreveport to Houston in the 1960s in search of games. Read fascinating yarns about life on the rough and tumble, and colorful adventures as a road gambler; feel the fear and frustration of being hijacked, getting arrested for playing poker, and having to outwit card sharps and scam artists. Wolford survived it all to win a gold bracelet at the World Series playing with poker greats Amarillo Slim Preston, Johnny Moss and 1978 World Champion, Bobby Baldwin. Wolford also won 30 rodeo belt buckles. Baldwin says, Cowboy is probably the best gambling story teller in the world. Paperback: 304 pages Publisher: Cardoza; 1st Cardoza Ed edition (September 27, 2005) Language: English ISBN-10: 1580420834 ISBN-13: 978-1580420839 Product Dimensions: 5.5 x 0.8 x 8.5 inches Shipping Weight: 11.2 ounces (View shipping rates and policies) Average Customer Review: 4.6 out of 5 stars 6 customer reviews Best Sellers Rank: #976,332 in Books (See Top 100 in Books) #49 in Books > Sports & Outdoors > Rodeos #452 in Books > Humor & Entertainment > Puzzles & Games > Poker #1051 in Books > Sports & Outdoors > Individual Sports > Horses Cowboy Wolford is one of the all-time characters I've ever met.