STONE FREE by Tim Muldoon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Retrograde Ureteroscopic Management of Large Renal Calculi: a Single Institutional Experience and Concise Literature Review

JOURNAL OF ENDOUROLOGY Volume 32, Number 7, July 2018 ª Mary Ann Liebert, Inc. Pp. 603–607 DOI: 10.1089/end.2018.0069 Retrograde Ureteroscopic Management of Large Renal Calculi: A Single Institutional Experience and Concise Literature Review Kymora B. Scotland, MD, PhD,1 Benjamin Rudnick, MD,2 Kelly A. Healy, MD,3 Scott G. Hubosky, MD,2 and Demetrius H. Bagley, MD2 Abstract Introduction: Advances in flexible ureteroscope design and accessory instrumentation have allowed for more challenging cases to be treated ureteroscopically. Here, we evaluate our experience with ureteroscopy (URS) for the management of large renal calculi (‡2 cm) and provide a concise review of recent reports. Methods: A retrospective review was undertaken of all URS cases between 2004 and 2014 performed by the endourologic team at a single academic tertiary care institution. We identified patients with at least one stone ‡2 cm managed with retrograde URS. Stone size was defined as the largest linear diameter of the index stone. Small diameter flexible ureteroscopes were used primarily with holmium laser. Patient demographics, in- traoperative data, and postoperative outcomes were evaluated. Results: We evaluated 167 consecutive patients who underwent URS for large renal stones ‡2 cm. The initial reason for choosing URS included patient preference (29.5%), failure of other therapies (8.2%), anatomic con- siderations/body habitus (30.3%), and comorbidities (28.8%). Mean patient age was 55.5 years (22–84). The mean stone size was 2.75 cm with mean number of procedures per patient of 1.65 (1–6). The single session stone-free rate was 57.1%, two-stage procedure stone-free rate was 90.2% and three-stage stone-free rate was 94.0%. -

Jimi Hendrix Songs for Groovy Children: the Fillmore East Concerts

Jimi Hendrix Songs For Groovy Children: The Fillmore East Concerts (19075982772) Expansive CD & LP Box Sets Present All Four Historic Hendrix Band of Gypsys Performances At The Fillmore East Newly Mixed by Eddie Kramer Songs For Groovy Children includes more than two dozen previously unreleased tracks October 1, 2019-New York, NY-Experience Hendrix L.L.C. and Legacy Recordings, a division of Sony Music Entertainment, are proud to release Songs For Groovy Children: The Fillmore East Concerts by Jimi Hendrix, on CD and digital November 22, with a vinyl release to follow on December 13. This collection assembles all four historic debut concerts by the legendary guitarist in their original performance sequence. The 5 CD or 8 vinyl set boasts over two dozen tracks that have either never before been released commercially or have been newly pressed and newly remixed. Those who pre-order the digital version will instantly receive the previously unreleased track “Message To Love,” from the New Year’s Eve second set performance on the collection. Pre-order Songs For Groovy Children here: https://jimihendrix.lnk.to/groovy Watch Songs Of Groovy Children album trailer: https://jimihendrix.lnk.to/groovyvid Over the course of four extraordinary years, Jimi Hendrix placed his indelible stamp upon popular music with breathtaking velocity. Measured alongside his triumphs at Monterey Pop and Woodstock, Hendrix’s legendary Fillmore East concerts illustrated a critical turning point in a radiant career filled with indefinite possibilities. The revolutionary impact Jimi Hendrix, Billy Cox and Buddy Miles had upon the boundaries and definitions of rock, R&B, and funk can be traced to four concerts over the course of two captivating evenings. -

Hendrix Hits London Educator Gallery Guide

Table of Contents: Background Information Education Goals Exhibition Walkthrough Extension Resources Background Information Hear My Train a Comin’: Hendrix Hits London The purpose of this guide is to present questions and offer information that help lead students through the exhibition and instigate a conversation about the dynamic themes highlighted therein. Hear My Train a Comin’: Hendrix Hits London delves deep into one of the most important and formative time periods in Jimi Hendrix’s career. During a nine-month period beginning in September 1966, Hendrix released three hit singles, an iconic debut album, and transformed into one of the most popular performers in the British popular music scene. In June 1967 he returned to America a superstar. This new exhibition furthers EMP Museum’s ongoing efforts to explore, interpret, and illuminate the life, career, and legacy of Jimi Hendrix. Before its installation in Seattle, Hear My Train a Comin’: Hendrix Hits London debuted at the Hospital Club, a creative exhibition facility and private club located in the heart of London. The show was on view in the UK for two months before returning to the US. While the overall theme remains the same, EMP sought to convey the look and feel of swinging London with the addition of richly patterned wall fabrics evocative of the era, interactive elements, and a chronological large-scale concert map. Hendrix: Biographical Information Students may benefit from a discussion of Hendrix’s personal history prior to the period covered in the exhibition. Born -

Jimi Hendrix Moonbeams & Fairytales Disc 19-22 Jimi Hendrix

Naughty Dog Jimi Hendrix Moonbeams & Fairytales Disc 19-22 T rade Freely. Not ForSale. rade Freely. Jimi Hendrix Moonbeams & Fairytales Disc 19-22 Disc Fairytales & Moonbeams Hendrix Jimi Naughty Dog Naughty Jimi Hendrix Moonbeams & Fairytales Disc 19-22 Jimi Hendrix Moonbeams And Fairytales Jimi Hendrix Moonbeams & Fairytales Disc 19-22 Naughty Dog Disc 19-22 Naughty Dog DISC 19 DISC TIME 71:31 DISC 20 DISC TIME 69:02 1967 1. 25 Oct [S026] (3) Little Wing (official, mono) 3:03 “Musicorama”, L’Olympia, Paris 2. 25 Oct [S026] (1) Little Wing (official stereo) 3:01 1. 09 Oct [L1582] (19) Hey Joe (inc. intro) 4:07 3. 25 Oct Little Wing (fake mix of (1) - Living Reels B528) 3:26 2. 09 Oct [L1542](14) Experiencing The Blues (Catfish Blues) 5:26 4. 25 Oct [S026] (2) Little Wing (“Backtrack” mix) 1:48 3. 09 Oct [L1583](95) Fire *†† 3:29 5. 25 Oct [S1540] (16) Little Wing (alternate instrumental take) 1:48 4. 09 Oct [L1581] (33) Stone Free *†† 3:41 5. 09 Oct [L521] (12) Foxy Lady 5:47 Olympic Sound Studios, 117 Church Road, Barnes, London SW13 6. 09 Oct [L522] (10) The Wind Cries Mary 4:14 6. 26 Oct [S024] (3) Wait until Tomorrow (official, mono) 1:48 7. 09 Oct [L523] (5) Rock Me Baby 4:54 7. 26 Oct [S024] (1) Wait until Tomorrow (official) 1:52 8. 09 Oct [L524] (9) Red House 7:30 8. 26 Oct [S1105] (2) Wait until Tomorrow (alt. mix, longer) 1:47 9. 09 Oct [L525] (20) Purple Haze 8:26 9. -

Dionysian Symbolism in the Music and Performance Practices of Jimi Hendrix

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Dissertations and Theses City College of New York 2013 Dionysian Symbolism in the Music and Performance practices of Jimi Hendrix Christian Botta CUNY City College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/cc_etds_theses/205 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Dionysian Symbolism in the Music and Performance Practice of Jimi Hendrix Christian Botta Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in Musicology At the City College of the City University of New York May 2013 Table of Contents Introduction 1 Chapter One – Hendrix at the Monterey Pop and Woodstock Festivals 12 Chapter Two – ‘The Hendrix Chord’ 26 Chapter Three – “Machine Gun” 51 Conclusion 77 Bibliography 81 i Dionysian Symbolism in the Music and Performance Practice of Jimi Hendrix Introduction Jimi Hendrix is considered by many to be the most innovative and influential electric guitarist in history. As a performer and musician, his resume is so complete that there is a tendency to sit back and marvel at it: virtuoso player, sonic innovator, hit songwriter, wild stage performer, outrageous dresser, sex symbol, and even sensitive guy. But there is also a tendency, possibly because of his overwhelming image, to fail to dig deeper into the music, as Rob Van der Bliek has pointed out.1 In this study, we will look at Hendrix’s music, his performance practice, and its relationship to the mythology that has grown up around him. -

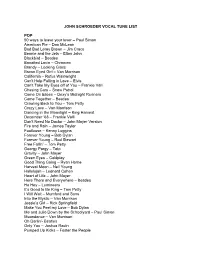

John Schroeder Vocal Tune List

JOHN SCHROEDER VOCAL TUNE LIST POP 50 ways to leave your lover – Paul Simon American Pie – Don McLean Bad Bad Leroy Brown – Jim Croce Bennie and the Jets – Elton John Blackbird – Beatles Bonafied Lovin – Chromeo Brandy – Looking Glass Brown Eyed Girl – Van Morrison California – Rufus Wainwright Can't Help Falling in Love – Elvis Can’t Take My Eyes off of You – Frankie Valli Chasing Cars – Snow Patrol Come On Eileen – Dexy’s Midnight Runners Come Together – Beatles Crawling Back to You – Tom Petty Crazy Love – Van Morrison Dancing in the Moonlight – King Harvest December ‘63 – Frankie Valli Don’t Need No Doctor – John Mayer Version Fire and Rain – James Taylor Footloose – Kenny Loggins Forever Young – Bob Dylan Forever Young – Rod Stewart Free Fallin’ – Tom Petty Georgy Porgy – Toto Gravity – John Mayer Green Eyes – Coldplay Good Thing Going – Ryan Horne Harvest Moon – Neil Young Hallelujah – Leonard Cohen Heart of Life – John Mayer Here There and Everywhere – Beatles Ho Hey – Lumineers It’s Good to Be King – Tom Petty I Will Wait – Mumford and Sons Into the Mystic – Van Morrison Jessie’s Girl – Rick Springfield Make You Feel my Love – Bob Dylan Me and Julio Down by the Schoolyard – Paul Simon Moondance – Van Morrison Oh Darlin’- Beatles Only You – Joshua Radin Pumped Up Kicks – Foster the People Rapid Roy – Jim Croce Riptide – Vance Joy Saw Her Standing There – Beatles Shut Up and Dance – Walk the Moon Somebody I Used to Know - Gotye Somebody’s Baby – Jackson Browne Steal Away – Bobby Dupree Stuck in the Middle With You – Stealers Wheel -

WCXR 2004 Songs, 6 Days, 11.93 GB

Page 1 of 58 WCXR 2004 songs, 6 days, 11.93 GB Artist Name Time Album Year AC/DC Hells Bells 5:13 Back In Black 1980 AC/DC Back In Black 4:17 Back In Black 1980 AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long 3:30 Back In Black 1980 AC/DC Have a Drink on Me 3:59 Back In Black 1980 AC/DC Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap 4:12 Dirty Deeds Done Dirt… 1976 AC/DC Squealer 5:14 Dirty Deeds Done Dirt… 1976 AC/DC Big Balls 2:38 Dirty Deeds Done Dirt… 1976 AC/DC For Those About to Rock (We Salute You) 5:44 For Those About to R… 1981 AC/DC Highway to Hell 3:28 Highway to Hell 1979 AC/DC Girls Got Rhythm 3:24 Highway to Hell 1979 AC/DC Beating Around the Bush 3:56 Highway to Hell 1979 AC/DC Let There Be Rock 6:07 Let There Be Rock 1977 AC/DC Whole Lotta Rosie 5:23 Let There Be Rock 1977 Ace Frehley New York Groove 3:04 Ace Frehley 1978 Aerosmith Make It 3:41 Aerosmith 1973 Aerosmith Somebody 3:46 Aerosmith 1973 Aerosmith Dream On 4:28 Aerosmith 1973 Aerosmith One-Way Street 7:02 Aerosmith 1973 Aerosmith Mama Kin 4:29 Aerosmith 1973 Aerosmith Rattkesnake Shake (live) 10:28 Aerosmith 1971 Aerosmith Critical Mass 4:52 Draw the Line 1977 Aerosmith Draw The Line 3:23 Draw the Line 1977 Aerosmith Milk Cow Blues 4:11 Draw the Line 1977 Aerosmith Livin' on the Edge 6:21 Get a Grip 1993 Aerosmith Same Old Song and Dance 3:54 Get Your Wings 1974 Aerosmith Lord Of The Thighs 4:15 Get Your Wings 1974 Aerosmith Woman of the World 5:50 Get Your Wings 1974 Aerosmith Train Kept a Rollin 5:33 Get Your Wings 1974 Aerosmith Seasons Of Wither 4:57 Get Your Wings 1974 Aerosmith Lightning Strikes 4:27 Rock in a Hard Place 1982 Aerosmith Last Child 3:28 Rocks 1976 Aerosmith Back In The Saddle 4:41 Rocks 1976 WCXR Page 2 of 58 Artist Name Time Album Year Aerosmith Come Together 3:47 Sgt. -

Jimi Hendrix

JIMI HENDRIX BIOGRAFIA Jimi Hendrix não foi um músico excepcional no sentido exacto da palavra. Autodidata e canhoto, tocava de maneira completamente estranha uma guitarra Fender Stratocaster para destros, com as cordas invertidas. Revolucionou a maneira de tocar guitarra, desenvolvendo o uso da alavanca e principalmente dos pedais conhecidos como wha-wha. Mais do que isso colocou a figura do guitarrista como principal personagem nas bandas de rock. Seus solos e riffs foram uma das principais raízes para o nascimento do heavy metal. Johnny Allen Hendrix nasceu em Seattle, Washington, em 1942. O seu nome foi posteriormente alterado pelo pai ainda durante a infância para James Marshall Hendrix. Aos 16 anos começou a tocar violão, participando num grupo chamado Velvetones. Aos 17 recebeu do pai uma guitarra eléctrica e entrou para o grupo Rocking Kings que mais tarde mudaria de nome para Thomas & The Tomcats. Jimi resolveu abandonar a escola e entrar para um batalhão de pára-quedismo do exército, de onde foi logo desligado em virtude de uma fractura no joelho. Sem a escola e não podendo mais seguir carreira no exército decidiu dedicar-se exclusivamente à música, tocando em bares e clubes com o amigo Billy Cox em numa banda chamada King Kasuals. Em 1963 Mudaram-se para Nova York, onde actuou também como músicos de estúdio, gravando e tocando com os Isley Brothers, Jackie Wilson e Sam Cooke. Em 1965, numa de muitas apresentações ao vivo como acompanhante de bandas diversas, Jimi chamou a atenção de Little Richard, grande astro e pioneiro do rock and roll dos anos 50. -

Voodoo Child

the most impactful periods of Hendrix’s career. Fans have called out for their induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. Just this year, the group with inducted into the Rhythm and Blues Hall of Fame. And authors Corey Washington and Nelson George have VOODOO written volumes on how the group has impacted generations of predominately black-oriented audiences and musicians alike. So it with great fanfare that Experience Hendrix has compiled the four shows in the new box set, being released as both a 5-CD and 8- LP package, Songs for Groovy Children. The name of the album comes from a remark Hendrix made right before they break into CHILD “Power of Soul” in their final show. The package comes complete with the band’s story told by Billy Cox, along with an essay by Nelson George demonstrating the impact it had on him and black JIMI HENDRIX INFORMATION MANAGEMENT INSTITUTE audiences. [email protected] Over the years, bits and pieces of these concerts have been www.facebook.com/groups/251427364936379/ released, this being the first comprehensive, albeit still incomplete, package of the four iconic concerts. There are 13 new, never before ISSUE 112 FALL 2019 commercially released songs, as well as two songs which have never appeared either commercially or through collector unauthorized This may be one of the most exciting, and the most frustrating editions. Overall, there are over two dozen tracks “that have either periods for Jimi Hendrix fans. On one hand, Experience Hendrix has never before been released commercially or have been newly pressed announced the release of the Band of Gypsys concerts at the Fillmore and newly remixed,” according to the project press release. -

Jimi Hendrix Stone Free

Stone Free Jimi Hendrix Everyday in the week I'm in a different city If I stay too long people try to pull me down They talk about me like a dog Talkin' about the clothes I wear But they don't realize they're the ones who's square Yeah! And that's why You can't hold me down I don't want to be tide down I gotta move Hey I said Stone free do what I please Stone free to ride the breeze Stone free, baby I can't stay I got to got to got to get away Yeah Listen here baby A woman here a woman there try to keep me in a plastic cage But they don't realize it's so easy to break Yeah but a sometimes I get a ha Feel my heart kind a gettin' hot That's when I got to move before I get caught So dig this And the is why, listen to me baby, you can't hold me down I don't want to be tied down I gotta move on I said Stone free do what I please Stone free to ride the breeze Stone free I can't stay Got to got to got to get away Yeah Tear me loose baby Hey Yeah! I said Stone free to ride on the breeze Stone free do what I please Stone free I can't stay Stone free I got to I got to get away Hey Stone free go on down the highway Stone free don't try to hold me back baby Stone free stone free Stone free got to baby Stone free got get on Tištěno z pisnicky-akordy.cz Sponzor: www.srovnavac.cz - vyberte si pojištění online! Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org). -

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT of STONES: Tions Appear at the End of the Article

1 Approved by the AUA Board of Directors April American Urological Association (AUA) 2016 Authors’ disclosure of po- Endourological Society Guideline tential conflicts of interest and author/staff contribu- SURGICAL MANAGEMENT OF STONES: tions appear at the end of the article. AMERICAN UROLOGICAL ASSOCIATION/ © 2016 by the American ENDOUROLOGICAL SOCIETY GUIDELINE Urological Association Dean Assimos, MD; Amy Krambeck, MD; Nicole L. Miller, MD; Manoj Monga, MD; M. Hassan Murad, MD, MPH; Caleb P. Nelson, MD, MPH; Kenneth T. Pace, MD; Vernon M. Pais Jr., MD; Margaret S. Pearle, MD, Ph.D; Glenn M. Preminger, MD; Hassan Razvi, MD; Ojas Shah, MD; Brian R. Matlaga, MD, MPH Purpose The purpose of this Guideline is to provide a clinical framework for the surgical management of patients with kidney and/or ureteral stones. Methods A systematic review of the literature using the Medline In-Process & Other Non- Indexed Citations, MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, and Scopus databases (search dates 1/1/1985 to 5/31/15) was conducted to identify peer-reviewed studies relevant to the surgical management of stones. The review yielded an evidence base of 1,911 articles after application of inclusion/exclusion criteria. These publications were used to create the guideline statements. If sufficient evidence existed, then the body of evidence for a particular treatment was assigned a strength rating of A (high quality evidence; high certainty), B (moderate quality evidence; moderate certainty), or C (low quality evidence; low certainty). Evidence-based statements of Strong, Moderate, or Conditional Recommendation, which can be supported by any body of evidence strength, were developed based on benefits and risks/burdens to patients. -

Jimi Hendrix

Jimi Hendrix This article is about the guitarist. For the band, see the began.”[2] Jimi Hendrix Experience. For other uses of Hendrix, Hendrix was the recipient of several music awards dur- see Hendrix (disambiguation). ing his lifetime and posthumously. In 1967, readers of Melody Maker voted him the Pop Musician of the Year, James Marshall "Jimi" Hendrix (born Johnny Allen and in 1968, Billboard named him the Artist of the Year Hendrix; November 27, 1942 – September 18, 1970) and Rolling Stone declared him the Performer of the Year. was an American guitarist, singer, and songwriter. Al- Disc and Music Echo honored him with the World Top though his mainstream career spanned only four years, he Musician of 1969 and in 1970, Guitar Player named him is widely regarded as one of the most influential electric the Rock Guitarist of the Year. The Jimi Hendrix Ex- guitarists in the history of popular music, and one of the perience was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of most celebrated musicians of the 20th century. The Rock Fame in 1992 and the UK Music Hall of Fame in 2005. and Roll Hall of Fame describes him as “arguably the Rolling Stone ranked the band’s three studio albums, Are greatest instrumentalist in the history of rock music”.[1] You Experienced, Axis: Bold as Love, and Electric La- Born in Seattle, Washington, Hendrix began playing gui- dyland, among the 100 greatest albums of all time, and tar at the age of 15. In 1961, he enlisted in the US Army; they ranked Hendrix as the greatest guitarist and the sixth he was granted an honorable discharge the following year.