Prairie Creek Redwoods State Park a History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Grizzly Creek Redwoods State Park 16949 Highway 36 Carlotta, CA 95528 (707) 777-3683

Our Mission The mission of California State Parks is Grizzly Creek to provide for the health, inspiration and hanks to lumberman education of the people of California by helping T to preserve the state’s extraordinary biological Redwoods diversity, protecting its most valued natural and Owen R. Cheatham, cultural resources, and creating opportunities State Park for high-quality outdoor recreation. these acres of redwoods were saved for all time—to inspire, dazzle and awe many California State Parks supports equal access. Prior to arrival, visitors with disabilities who future generations of need assistance should contact the park at (707) 777-3683. This publication is available park visitors. in alternate formats by contacting: CALIFORNIA STATE PARKS P.O. Box 942896 Sacramento, CA 94296-0001 For information call: (800) 777-0369. (916) 653-6995, outside the U.S. 711, TTY relay service www.parks.ca.gov Discover the many states of California.™ SaveTheRedwoods.org/csp Grizzly Creek Redwoods State Park 16949 Highway 36 Carlotta, CA 95528 (707) 777-3683 © 2011 California State Parks G rizzly Creek Redwoods State Park Hokan and Yukian. Though distinct from Rancheria, offers a sense of seclusion and intimacy one another, they still shared many cultural maintaining that has endeared it to generations of traits. Ethnographers have codified this cultural and visitors. Nearly 30 miles inland from the region as a Northern California culture area. ancestral coast, the lush, green, 393-acre park is Native groups traded with each other; local ties while an unspoiled gem. Towering ancient objects such as ceremonial blades and shell retaining and redwoods guard three separate parcels of beads have been identified as far away as practicing unspoiled riverfront. -

Ave Reg-Form 2014-V2

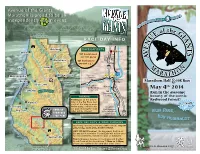

Avenue of the Giants Marathon is proud to be an independently green event. Portland 466 miles, 9 hours K RACE DAY INFO la m a th Orleans RACE DAY EXITS Redcrest Orick 101 Southbound 101 101 use exit 667A South North EXIT EXIT Redw Weitchpec 101 Northbound . 667A 667 use exit o 667 . o T d ri n Trinidad Cr Hupa i ty e Parking Head e R v k . STAGING 26.6 10k/13 & FINISH Willow Creek Albee Creek START START McKinleyville Campground R D LL C R E E K BU Dyerville Redding ek Arcata ll Cre Bridge 146 miles Bu Blue Lake 3 hours 6.5 Miles Humboldt 1st Marathon Weott Bay Turnaround EUREKA BOL 10K HUM DT Turnaround A V M E a 3.05 Miles O d PARKING F Burlington T H Campground E Ri Parking is on the gravel G I v A e flats of the Eel River just N r T Fortuna S north of the staging area. Ferndale Arrive early, vehicles that 19.6 Miles are parked along the road Half Marathon Rio Dell HUMBOLDT sides will be ticketed. & 2nd Marathon REDWOODS Turnaround STATE PARK S . F E RACE DAY EXITS & ROAD CLOSURES rk e . l On Sunday, all north south race traffic must use Hwy 101 E / e R exits 5 miles north of the START / FINISH. l R iv M e The Honeydew, South Fork T iv r HWY 101 Exit Closures: h a e e to r Eel and the Rockefeller Forest Exits will not be used L le o for race day traffic, but will be open on Saturday. -

County Profile

FY 2020-21 PROPOSED BUDGET SECTION B:PROFILE GOVERNANCE Assessor County Counsel Auditor-Controller Human Resources Board of Supervisors Measure Z Clerk-Recorder Other Funds County Admin. Office Treasurer-Tax Collector Population County Comparison Education Infrastructure Employment DEMOGRAPHICS Geography Located on the far North Coast of California, 200 miles north of San Francisco and about 50 miles south of the southern Oregon border, Humboldt County is situated along the Pacific coast in Northern California’s rugged Coastal (Mountain) Ranges, bordered on the north SCENERY by Del Norte County, on the east by Siskiyou and Trinity counties, on the south by Mendocino County and on the west by the Pacific Ocean. The climate is ideal for growth The county encompasses 2.3 million acres, 80 percent of which is of the world’s tallest tree - the forestlands, protected redwoods and recreational areas. A densely coastal redwood. Though these forested, mountainous, rural county with about 110 miles of coastline, trees are found from southern more than any other county in the state, Humboldt contains over forty Oregon to the Big Sur area of percent of all remaining old growth Coast Redwood forests, the vast California, Humboldt County majority of which is protected or strictly conserved within dozens of contains the most impressive national, state, and local forests and parks, totaling approximately collection of Sequoia 680,000 acres (over 1,000 square miles). Humboldt’s highest point is sempervirens. The county is Salmon Mountain at 6,962 feet. Its lowest point is located in Samoa at home to Redwood National 20 feet. Humboldt Bay, California’s second largest natural bay, is the and State Parks, Humboldt only deep water port between San Francisco and Coos Bay, Oregon, Redwoods State Park (The and is located on the coast at the midpoint of the county. -

2021 Redwood National and State Parks Visitor Guide

Redwood National Park Redwood National and State Parks Jedediah Smith Redwoods State Park Del Norte Coast Redwoods State Park Prairie Creek Redwoods State Park Visitor Guide The offcial 2021 visitor guide of Redwood National and State Parks PHOTO / STEVE OLSON Park Map Big Trees Scenic Drives Change Discover the best way to navigate Redwood’s Learn about the three kinds of redwood trees The type of vehicle you drive will determine mosaic of habitats…pages 6-7 and the best places to see them…page 5 which roads are suitable for you…page 7 The Superintendents of Redwood National D a v i l s rai Cree oad o T st Man k R n o n Lo and State Parks welcome you to relax and R a s o d avi D k 101 To Bald Hills Road ee L r il o C a st enjoy one of the most peaceful places Elk Meadow Day Use Area r M ie T ir n a l a o n Creek Trai r is P v a Berry Glen Trail D on earth. These forests provide sanctuary Other trails 3 l l i m a i from the stresses of fast-paced modern l r e Picnic area T s f s r ll o a m Parking area F E l k k life, steadfast and appearing unchanged m u M illi Tr e Restrooms a d ow to over eons. But no place is untouched by LB J G Lady Bird Johnson B r e ov Grove Trail r e j ry ct. -

Request for Proposal for Redwoods Rising Forest & Road Restoration

Request for Proposal for Redwoods Rising Forest & Road Restoration Operations October 2019 INTRODUCTION In partnership with the National Park Service (NPS) and the California Department of Parks and Recreation (CDPR), Save the Redwoods League (the League) is seeking proposals for services to conduct ecological restoration activities including forest thinning, road improvement and removal, and stockpiling large pieces of wood to be installed in creeks as aquatic habitat structures within Redwood National and State Parks (RNSP). This project is expected to last for several years, and it is the partnership’s intent to develop a long-term relationship with a trusted operator to implement a complex suite of activities across multiple watersheds, forest types, and road conditions. Competitive proposals will assure high quality and timely work, transparency in practices and accounting, will employ local labor where possible, and demonstrated commitment to long-term stewardship. SECTION 1. PROJECT DESCRIPTIONS Overview RNSP includes Redwood National Park, Del Norte Coast Redwoods State Park, Jedediah Smith Redwoods State Park, and Prairie Creek Redwoods State Parks. The parks are home to 45 percent of the world’s remaining protected old-growth redwoods. However, alongside these remaining primeval redwood stands are large swaths of forest that bear the scars of logging, including eroding roads, degraded streams, and unnaturally dense forest stands. The park’s diverse landscape supports a wide variety of habitats and ecosystems (e.g., coastal dune/scrub, forests, woodlands, grasslands) and essential habitat for threatened, endangered, and special status species such as marbled murrelet, northern spotted owl, and salmonids such as coho salmon, chinook salmon, and steelhead trout. -

Ancient Redwood Forest Redwood Ancient

Avenue2011Brochure.qxd:Avenue2006.qxd 5/19/11 2:06 AM Page 1 UC EEEC A SLCTDISD O ORCONVENIENCE YOUR FOR INSIDE LOCATED IS MAP REFERENCE QUICK A (707) (707) Near Fortuna riverbarfarm.com 9272 768 Massage by Peter by Massage Fri & Sat—Live Music Sat—Live & Fri Dr., Redway 1055 (707) 923-2748 Redway MASSAGE Persimmons Persimmons Garden Gallery & Wine Tasting Wine & Gallery Garden - 5 - New and used items, antiques, clothing. Open Tue. - Sat., 11 Sat., - Tue. Open clothing. antiques, items, used and New guests, it is our gift to the traveling public. traveling the to gift our is it guests, PM AM treesofmystery.net (707) (707) Ave, Wildwood 117 one of the finest private collections in the world. Free to our to Free world. the in collections private finest the of one 499-1654 Dell Rio redwood facts. Our End of the Trail Native American Museum is Museum American Native Trail the of End Our facts. redwood Second Chance Second trees and unique formations with interpretive signs and little-known and signs interpretive with formations unique and trees Buy, sell, trade, appraisals, restorations, gifts and gab. and gifts restorations, appraisals, trade, sell, Buy, Trees of Mystery Forest Experience trails to see many noteworthy many see to trails Experience Forest Mystery of Trees Upstairs—Jacob Garber Square, Square, Garber Upstairs—Jacob 986-7747 Garberville (707) glides you silently through the forest canopy. Hike or stroll the stroll or Hike canopy. forest the through silently you glides Lost Coast Vintage Guitars Vintage Coast Lost gondola SkyTrail a as redwoods the of view bird’s-eye a Enjoy ™ 16 miles south of Crescent City on Hwy 101 101 Hwy on City Crescent of south miles 16 800-638-3389 800-638-3389 ATTRACTIONS & GIFT SHOPS GIFT & ATTRACTIONS Trees of Mystery of Trees ™ Victorian Inn: Victorian VictorianVillageInn.com see our beautiful glasswork. -

Spring 2017 Humboldt Redwoods Interpretive Association

NEWSLETTER Spring 2017 Humboldt Redwoods Interpretive Association Vice President’s Report: Alan Aitken Welcome to summer. The Visitor Center is open and visitors have arrived. Sunday, June 19th was a record day for people from across the country and around the world coming through our door at Humboldt Redwoods State Park. Our most dedicated volunteer, June Patton, with more than 19,000 hours serving HRIA for over 30 years, has entered retirement at the age of 96. She has transitioned to an assisted care facility where by all accounts she is having a great time. Everyone at HRIA will miss her. Thank you, June, seems so inadequate. At the May board meeting HRIA decided to enter into an agreement with the Discover Nature Co. to create an application that our visitors can download to receive trail maps, information on the park, an interactive children's challenge, and once downloaded will be able to tell you your location within the park using our phones GPS function. Life member of HRIA, Jarl DeBoer, will be donating his postcard collection of the Redwood Highway to the HRIA library. Jarl has been collecting postcards for over 45 years and there are over 1,600 postcards in this collection. There will be a reception and presentation of the collection on Saturday, July 15th at 2pm at the Humboldt Redwoods State Park Visitor Center. Hoping your summer is relaxing. The Visitor Centers will be very busy. Time to relax will come in the fall. Alan Ait ken Photo by Allan Weigman 1 BOARD OF DIRECTORS Officers Alan Aitken – Vice President ONGOING EVENTS! Carla Thomas – Secretary Maralyn Renner – Treasurer Cathy Mathena –MAU Board Members Dana Johnston Dave Stockton David Pritchard Co-op. -

Initial Study Mitigated Negative Declaration

DRAFT INITIAL STUDY MITIGATED NEGATIVE DECLARATION Fox Camp Prairie Restoration Project Humboldt Redwoods State Park April 2012 State of California DEPARTMENT OF PARKS AND RECREATION DRAFT INITIAL STUDY MITIGATED NEGATIVE DECLARATION Fox Camp Prairie Restoration Project Humboldt Redwoods State Park April 2012 State of California DEPARTMENT OF PARKS AND RECREATION MITIGATED NEGATIVE DECLARATION PROJECT: Fox Camp Prairie Restoration Project LEAD AGENCY: California Department of Parks and Recreation AVAILABILITY OF DOCUMENTS: This Initial Study/Mitigated Negative Declaration is available for review at: California Department of Parks and Recreation Northern Service Center One Capitol Mall – Suite 410 Sacramento, CA 95814 California Department of Parks and Recreation North Coast Redwoods District 3431 Fort Avenue Eureka, CA 95503 Humboldt Redwoods State Park 17119 Avenue of the Giants Weott, CA 95571 Humboldt County Public Library 1313 Third Street Eureka, CA 95501 California Department of Parks and Recreation Internet Website. http://parks.ca.gov/default.asp?page_id=980 Fox Camp Prairie Restoration Project IS/MND Calif. Dept. of Parks and Recreation i PROJECT DESCRIPTION: California State Parks (CSP) proposes to restore prairie habitat by removing trees on up to 35 acres of closed canopy forests and adjacent small clumps of trees within a 102- acre project area. Active fire suppression and a lack of fire ignitions – historically ignited by Native Americans – has allowed trees to colonize these prairies and convert them into closed canopy forests. The encroaching trees are primarily Douglas-firs. Trees will either be removed by heavy equipment or will be felled with a chainsaw. An excavator or other piece of heavy equipment will be used to push over trees so that the root wads stay attached. -

Redwood Highway/Save the Redwoods Movement Susie Van Kirk

Humboldt State University Digital Commons @ Humboldt State University Susie Van Kirk Papers Special Collections 12-2015 Redwood Highway/Save the Redwoods Movement Susie Van Kirk Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.humboldt.edu/svk Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Van Kirk, Susie, "Redwood Highway/Save the Redwoods Movement" (2015). Susie Van Kirk Papers. 25. https://digitalcommons.humboldt.edu/svk/25 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Special Collections at Digital Commons @ Humboldt State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Susie Van Kirk Papers by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Humboldt State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REDWOOD HIGHWAY/SAVE THE REDWOODS MOVEMENT Research for State Parks project August 2013-April 2014 Engbeck, Joseph H., Jr., State Parks of California. 1980. Graphic Arts Center Publishing Co., Portland. Chapter 4. Save the Redwoods! Naturalists had explored the forests of the north coast region and some, including John Mur, were especially impressed by the extraordinary stand of redwoods alongside the South Fork of the Eel River at bull Creek and the nearby Dyerville Flat. These experts agreed that the coast redwood forest was at its magnificent best far to the north of San Francisco. Some authorities went so far as to say that the Bull Creek and Dyerville Flat area supported the most impressive and spectacular forest in the whole world…. In 1916 and 1917 several developments took place that would eventually have a profound impact on the north coast redwood region in general and the Bull Creek-Dyerville Flat area in particular. -

2009 Annual Report Welcome Pete Dangermond and Ruskin K

2009 Annual Report Welcome Pete Dangermond and Ruskin K. Hartley Dear Friends, This year, Save the Redwoods League adopted a mission statement to succinctly communicate what we do: “Save the Redwoods League protects and restores redwood forests and connects people with their peace and beauty so these wonders of the natural world flourish.” We continued to carry out this mission as we have since 1918, despite the challenging economic climate. With our members’ and partners’ generous support in fiscal year 2008-9, we protected more than 1,100 acres of key redwood forestlands valued at $8 million, and transferred 831 acres to state or national parks or reserves. This work brought the total number of acres the League has protected to more than 181,000. Our work continued as a world leader in two important endeavors: accelerating restoration of the logged Mill Creek forest to a majestic state, and developing a strategy to help redwoods survive rapid climate change. To sustain our work in the future, we continued to grow future redwoods stewards by awarding 37 grants that helped 63,000 children and adults experience and want to protect redwoods. These accomplishments would not have been possible without the generosity of our members and partners. We extend our sincere thanks, and we look forward to your steadfast support to help save redwoods—sources of peace and beauty for people today and in centuries to come. Pete Dangermond Ruskin K. Hartley Board President Executive Director and Secretary Photo: Erin Derkatz Save the Redwoods League 2009 Annual Report Welcome Pete Dangermond and Ruskin K. -

Save the Redwoods League, National Park Service and California State Parks Unite to Bring Back Ancient Redwood Forest on the North Coast of California

PRESS RELEASE FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE April 16, 2018 Media Contacts: Save the Redwoods League: Ashley Boarman, Landis Communications, Inc. Phone: (415) 359-2312 | Email: [email protected] National Park Service: Leonel Arguello Phone: (707) 465-7780 | Email: [email protected] California State Parks: Gloria Sandoval Phone: (916) 651-7661 | Email: [email protected] Save the Redwoods League, National Park Service and California State Parks Unite to Bring Back Ancient Redwood Forest on the North Coast of California New initiative, Redwoods Rising, fast-tracks the growth of healthy redwood forests on 80,000 acres of parklands — providing clean air and water, storing carbon and fighting climate change San Francisco (April 16, 2018) – Save the Redwoods League (League), the National Park Service (NPS) and California State Parks (State Parks) today announced a new commitment to heal previously-harvested redwood forests through a collaboration known as Redwoods Rising. One of the goals in the coming decades is to bring back stands of towering coast redwoods (Sequoia sempervirens) on 80,000 acres of public lands in Redwood National and State Parks (RNSP). Redwoods Rising creates an unprecedented level of collaboration between these three organizations to restore the redwood forests and ensure the parks’ entire 120,000 acres exist as a connected forest ecosystem and a thriving landscape that supports and protects the natural and cultural treasures found there. “If our greatest responsibility is to leave the world better than we found it, then healing the redwood forest represents an opportunity of a lifetime. We can actually restore and grow the old-growth forests of the future,” said Sam Hodder, president and CEO of Save the Redwoods League. -

Save the Redwoods League, National Park Service, and California State Parks Launch Historic Forest Restoration Program, “Redwoods Rising,” on Fri, April 27

Contact: David Cumpston, Landis Communications Inc. (415) 359-2316 [email protected] www.landispr.com ** MEDIA ADVISORY ** SAVE THE REDWOODS LEAGUE, NATIONAL PARK SERVICE, AND CALIFORNIA STATE PARKS LAUNCH HISTORIC FOREST RESTORATION PROGRAM, “REDWOODS RISING,” ON FRI, APRIL 27 Event at Prairie Creek Redwoods State Park in Orick, Calif. Celebrates Unprecedented Collaboration to Bring Back Forests of Giant Coast Redwoods on 80,000 Acres of Public Lands PHOTO AND VIDEO OPP: FRI, APRIL 27 (11:30 PM – 2 PM) SAN FRANCISCO (ApriL 24, 2018) — Save the Redwoods LeaGue, the National Park Service and California State Parks today announced the kickoff of Redwoods RisinG, a collaborative effort to restore the historically loGGed redwood forest within Redwood National and State Parks. Executives representinG the three orGanizations will siGn a Memorandum of UnderstandinG (MOU) on Friday, April 27 at Prairie Creek Redwoods State Park in Orick outlining the proGram commitments and its benefits. State Senator Mike McGuire and Assemblymember Jim Wood will speak about the importance of the north coast redwood forests and local communities to California. WHAT: • Redwoods RisinG creates an unprecedented level of collaboration and efficiency between these three orGanizations. Their collective Goal is to restore the redwood forests while coordinatinG on efforts to increase public enGaGement and sustainable financial support for restoration. • To fast-track the regrowth of healthy redwood forest ecosystems in this reGion, Redwoods RisinG will utilize scientifically verified methods of restoration tree thinninG, removal of old loGGinG roads and invasive species, and restoration of waterways and watersheds. • For more information, please visit RedwoodsRisinG.orG. WHEN: • Friday, April 27, 2018 from 11:30 am to 2 pm Two panoramic photos comparing conditions in an old growth forest (top) and a neighboring Event Timeline: second growth forest (bottom) in Prairie Creek o 11:30 am - BBQ lunch Redwoods State Park.