Dialectics of Protest and Resistance in Portland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download a PDF of the Toolkit Here

This toolkit was created through a collaboration with MediaJustice's Disinfo Defense League as a resource for people and organizations engaging in work to dismantle, defund, and abolish systems of policing and carceral punishment, while also navigating trials of police officers who murder people in our communities. Trials are not tools of abolition; rather, they are a (rarely) enforced consequence within the current system under the Prison Industrial Complex (PIC) for people who murder while working as police officers. Police are rarely charged when they commit these murders and even less so when the victim is Black. We at MPD150 are committed to the deconstruction of the PIC in its entirety and until this is accomplished, we also honor the need for people who are employed as police officers to be held to the same laws they weaponize against our communities. We began working on this project in March of 2021 as our city was bracing for the trial of Derek Chauvin, the white police officer who murdered George Floyd, a Black man, along with officers J. Alexander Kueng and Thomas Lane while Tou Thao stood guard on May 25th, 2020. During the uprising that followed, Chauvin was charged with, and on April 20th, 2021 ultimately found guilty of, second-degree unintentional murder, third-degree murder, and second-degree manslaughter. Municipalities will often use increased police presence in an attempt to assert control and further criminalize Black and brown bodies leading up to trials of police officers, and that is exactly what we experienced in Minneapolis. During the early days of the Chauvin trial, Daunte Wright, a 20-year-old Black man was murdered by Kim Potter, a white Brooklyn Center police officer, during a traffic stop on April 11th, 2021. -

February 12, 2021 Michael E. Horowitz United States Department

February 12, 2021 Michael E. Horowitz United States Department of Justice Office of the Inspector General 950 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW Washington, DC 20530-0001 Dear Mr. Horowitz, I write today to convey my deep concern regarding the disparate treatment of Black protesters in defense of Black lives and the white supremacist insurrectionists who stormed the Capitol Building. The attack on the U.S. Capitol on January 6th, in which a mob of insurrectionists illegally and violently stormed the halls of Congress, justifiably terrified our country. It was a shameful act that will forever stain this nation’s history. In the days since January 6th, it has become clear that this mob of insurrectionists barged through the U.S. Capitol to disrupt the peaceful transfer of power and suppress the votes of millions of Black, brown, and Indigenous people. Incited by former President Donald Trump, 800 insurrectionists breached the first security perimeter of the Capitol Building, some heavily armed and prepared to 1 carry out acts of violence. They stormed the U.S. Capitol, barreled past fences, barricades and walls, and climbed over protective barriers and through broken windows. They then made their way to the second-floor lobby and into the Senate Chamber. One woman was shot, and later pronounced dead, 2 and four other people died on Capitol grounds, including a U.S. Capitol Police officer. Police seized five guns.3 Of the 800 people who stormed the Capitol Building, 206 people have been arrested, and charged, 4 many of them charged with violating curfew laws. It has come to my attention that Eric Muchel, one of the insurrectionists who came prepared to hold Members of Congress hostage, was released on 1 Kaya Yurieff. -

Pdfblackmillennialmovement V Trump.Pdf

Case 3:20-cv-01464-YY Document 1 Filed 08/26/20 Page 1 of 61 Per A. Ramfjord, OSB No. 934024 [email protected] Jeremy D. Sacks, OSB No. 994262 [email protected] Crystal S. Chase, OSB No. 093104 [email protected] STOEL RIVES LLP 760 SW Ninth Ave, Suite 3000 Portland, OR 97205 Telephone: (503) 224-3380 Kelly K. Simon, OSB No. 154213 [email protected] ACLU FOUNDATION OF OREGON 506 SW 6th Ave, Suite 700 Portland, OR 97204 Telephone: (503) 227-3986 Attorneys for Plaintiffs Mark Pettibone, Fabiym Acuay (a.k.a. Mac Smiff), Andre Miller, Nichol Denison, Maureen Healy, Christopher David, Duston Obermeyer, James McNulty, Black Millennial Movement, and Rose City Justice, Inc. [Additional counsel for Plaintiffs listed on signature page] UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT DISTRICT OF OREGON PORTLAND DIVISION MARK PETTIBONE, an individual; Case No.: 3:20-cv-1464 FABIYM ACUAY (a.k.a., MAC SMIFF), an individual; COMPLAINT ANDRE MILLER, an individual; NICHOL DENISON, an individual; (28 U.S.C. § 1332) MAUREEN HEALY, an individual; CHRISTOPHER DAVID, an individual; DEMAND FOR JURY TRIAL DUSTON OBERMEYER, an individual; JAMES MCNULTY, an individual; BLACK MILLENNIAL MOVEMENT, an organization; and ROSE CITY JUSTICE, INC., an Oregon nonprofit corporation, Page 1 - COMPLAINT 107810438.1 0099880-01343 Case 3:20-cv-01464-YY Document 1 Filed 08/26/20 Page 2 of 61 Plaintiffs, v. DONALD J. TRUMP, in his official capacity; CHAD F. WOLF, in his individual and official capacity; GABRIEL RUSSELL, in his individual and official capacity; JOHN DOES 1-200, in their individual capacities; UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF HOMELAND SECURITY; and UNITED STATES MARSHALS SERVICE, Defendants. -

Negotiating Motherhood and Intersecting Inequalities: a Qualitative Study of African American Mothers and the Socialization of A

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Doctoral Dissertations University of Connecticut Graduate School 12-15-2017 Negotiating Motherhood and Intersecting Inequalities: A Qualitative Study of African American Mothers and the Socialization of Adolescent Daughters Brandyn-Dior McKinley University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation McKinley, Brandyn-Dior, "Negotiating Motherhood and Intersecting Inequalities: A Qualitative Study of African American Mothers and the Socialization of Adolescent Daughters" (2017). Doctoral Dissertations. 1665. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations/1665 Negotiating Motherhood and Intersecting Inequalities: A Qualitative Study of African American Mothers and the Socialization of Adolescent Daughters Brandyn-Dior McKinley, PhD University of Connecticut, 2017 African American middle-class mothers have been understudied in gender and family studies research. To address this gap in the literature, this dissertation uses an intersectional framework to document the raced, classed, and gendered experiences of African American middle-class mothers raising adolescent daughters. Data collected from thirty-six interviews indicated that mothers try to reconcile cultural definitions of motherhood with their present-day social and economic realities. Due to persistent race and class segregation in the United States, mothers and their families spend a considerable amount of time in predominantly white settings. Because mothers do not assume their class status will shield their children from racial bias, mothers engaged in different types of care work to promote their daughters’ educational, emotional, and social development. This included monitoring their daughters’ school environments, helping their daughters develop resistance strategies to combat the effects of discrimination, and constructing culturally affirming support networks. -

BLACK LIVES MATTER (BLM)Poetry

BLACK LIVES MATTER (BLM)Poetry: By : Janaya Cooper Dr.Saundra Collins, Independent Studies Advisor, Black Psychology and Black Sociology Research Project for Black Psychology and Black Sociology of Black Lives Matter Dr.Zoe Burkholder, Internship Coordinator, MSU Human Rights Education Internship MSU Human Rights Education Internship, Black Lives Matter Movement December 20,2016 Dear Emmett Till I hear it was the whistling towards a white woman, that got you killed, face beaten in like a castrated mummy. They stopped you because they did not want to take the blame. Oh! how they killed you because they hated themselves, used a lie to send you to your grave in the most horrible way. Blood stains the Coliseum doors. Now history repeats, everyone getting killed like Till. Dead Black bodies dropping down on the streets. Shout all of their names 3 times! They were innocent Black people, but 5-0 thought otherwise. Police took away precious black lives of men, women, and children. I know I’m guilty of it too, but not like them. Stop the killing! Stop the racism! Freeze! Black people are no longer enslaved, We no longer wear those chains just to be painted gold. Now once upon a time not too long ago, A nigga like myself had to strong arm a hoe. Hold your golden-black crown high Black woman Black woman What do you see when you look in the mirror? Do you see the strength and heart of the warrior Afrekete? Is your head held up high, for a crown to rest? And be dubbed black queen, mother of life, educator of black intelligence Do you see your dark skin as it dances and befriends the night, kisses the sun and absorbs black power day in and day out? Do you see those wide hips, big bust, big butt and big lips? Never will you say that those precious gifts from descendant Saartjie Baartman are a curse. -

Talking Book Topics September-October 2019

Talking Book Topics September–October 2019 Volume 85, Number 5 Need help? Your local cooperating library is always the place to start. For general information and to order books, call 1-888-NLS-READ (1-888-657-7323) to be connected to your local cooperating library. To find your library, visit www.loc.gov/nls and select “Find Your Library.” To change your Talking Book Topics subscription, contact your local cooperating library. Get books fast from BARD Most books and magazines listed in Talking Book Topics are available to eligible readers for download on the NLS Braille and Audio Reading Download (BARD) site. To use BARD, contact your local cooperating library or visit nlsbard.loc.gov for more information. The free BARD Mobile app is available from the App Store, Google Play, and Amazon’s Appstore. About Talking Book Topics Talking Book Topics, published in audio, large print, and online, is distributed free to people unable to read regular print and is available in an abridged form in braille. Talking Book Topics lists titles recently added to the NLS collection. The entire collection, with hundreds of thousands of titles, is available at www.loc.gov/nls. Select “Catalog Search” to view the collection. Talking Book Topics is also online at www.loc.gov/nls/tbt and in downloadable audio files from BARD. Overseas Service American citizens living abroad may enroll and request delivery to foreign addresses by contacting the NLS Overseas Librarian by phone at (202) 707-9261 or by email at [email protected]. Page 1 of 84 Music scores and instructional materials NLS music patrons can receive braille and large-print music scores and instructional recordings through the NLS Music Section. -

Black Lives Matter: Eliminating Racial Inequity in the Criminal Justice

BLACK LIVES MATTER: ELIMINATING RACIAL INEQUITY IN THE CRIMINAL JUSTICE SYSTEM For more information, contact: This report was written by Nazgol Ghandnoosh, Ph.D., Research Analyst at The Sentencing Project. The report draws on a 2014 publication The Sentencing Project of The Sentencing Project, Incorporating Racial Equity into Criminal 1705 DeSales Street NW Justice Reform. 8th Floor Washington, D.C. 20036 Cover photo by Brendan Smialowski of Getty Images showing Congressional staff during a walkout at the Capitol in December 2014. (202) 628-0871 The Sentencing Project is a national non-profit organization engaged sentencingproject.org in research and advocacy on criminal justice issues. Our work is twitter.com/sentencingproj supported by many individual donors and contributions from the facebook.com/thesentencingproject following: Atlantic Philanthropies Morton K. and Jane Blaustein Foundation craigslist Charitable Fund Ford Foundation Bernard F. and Alva B. Gimbel Foundation General Board of Global Ministries of the United Methodist Church JK Irwin Foundation Open Society Foundations Overbrook Foundation Public Welfare Foundation Rail Down Charitable Trust David Rockefeller Fund Elizabeth B. and Arthur E. Roswell Foundation Tikva Grassroots Empowerment Fund of Tides Foundation Wallace Global Fund Working Assets/CREDO Copyright © 2015 by The Sentencing Project. Reproduction of this document in full or in part, and in print or electronic format, only by permission of The Sentencing Project. TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary 3 I. Uneven Policing in Ferguson and New York City 6 II. A Cascade of Racial Disparities Throughout the Criminal Justice System 10 III. Causes of Disparities 13 A. Differential crime rates 13 B. Four key sources of unwarranted racial disparities in criminal justice outcomes 15 IV. -

What Is Police Violence? Plain Language Toolkit

What is Police Violence? A plain language booklet about anti-Black racism, police violence, and what you can do to stop it 1 Introduction We are writing this booklet in June of 2020. Right now, there are protests all over the country about racism and police violence. We wrote this booklet in plain language so as many people as possible can understand the protests. There is a lot to know about racism and police violence. We can’t talk about everything in this short booklet. We will tell you where to learn more. And, we will work on more resources. This booklet is just to get you started. Racism is when people are treated unfairly because of their race. Anti-Black racism is when Black people are treated unfairly because they are Black. People can do racist things. For example: Byron is Black. He wants to rent a house. Tyler is white. He owns a house, and wants to rent it out. Byron comes to see Tyler’s house. Tyler lies to Byron because Byron is Black. Tyler tells Byron that the house is not up for rent. Tyler only wants to rent his house to white people. Tyler was being racist when he lied to Byron. Society does racist things. For example: There are many times where a Black person and a white person do the same crime. Usually, the Black person will go to jail for longer. The white person might not even go to jail! The way our society deals with crime is racist. It is set up to hurt Black people. -

In Light of the Murder of George Floyd and Subsequent Police Violence

In light of the murder of George Floyd and subsequent police violence against protestors, the Public Interest Law Organization expresses solidarity with the Black Law Students Association and the Black Lives Matter movement at large. As future lawyers, judges, advocates, and professionals, we recognize our responsibility to be actively anti-racist in order to change a system that has been broken for too long. While the officers responsible for Floyd’s death were charged and arrested, oppression against people of color runs much deeper than any single act of violence. Floyd is just one of many black individuals who have been victims of racial injustice, police brutality, and social inequity. A few of the names we should not forget include Tony McDade, Breonna Taylor, Michael Ramos, and Ahmaud Arbery. In standing with the BLM movement, we also mourn these tragic losses of life. As an organization of students passionate about pursuing public interest through the law, we recognize that our justice system is founded on racial inequalities that have persisted for decades. To all persons of color within the UHLC community, please let us know how we can support you during this time. We pledge to work on our own biases, to educate others and learn how we can better fight for change, and to listen to our communities of color. In Solidarity, PILO at UH Law Katherine Powell, President Jennifer Ren, Vice-President of On-Campus Affairs Monica Wadleigh, Vice-President of Off-Campus Outreach Samantha Casas, Secretary Emory Powers, Treasurer . -

Download the Letter

This letter is embargoed until Friday, June 5, 10:00am (EST) To Members of the United Nations Human Rights Council Re: Request for the Convening of a Special Session on the Escalating Situation of Police Violence and Repression of Protests in the United States Excellencies, The undersigned family members of victims of police killings and civil society organizations from around the world, call on member states of the U.N. Human Rights Council to urgently convene a Special Session on the situation of human rights in the United States in order to respond to the unfolding grave human rights crisis born out of the repression of nationwide protests. The recent protests erupted on May 26 in response to the police murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis, Minnesota, which was only one of a recent string of unlawful killings of unarmed Black people by police and armed white vigilantes. We are deeply concerned about the escalation in violent police responses to largely peaceful protests in the United States, which included the use of rubber bullets, tear gas, pepper spray and in some cases live ammunition, in violation of international standards on the use of force and management of assemblies including recent U.N. Guidance on Less Lethal Weapons. Additionally, we are greatly concerned that rather than using his position to serve as a force for calm and unity, President Trump has chosen to weaponize the tensions through his rhetoric, evidenced by his promise to seize authority from Governors who fail to take the most extreme tactics against protestors and to deploy federal armed forces against protestors (an action which would be of questionable legality). -

Cornerstones of Community: Building of Portland's African American History

Portland State University PDXScholar Black Studies Faculty Publications and Presentations Black Studies 8-1995 Cornerstones of Community: Buildings of Portland's African American History Darrell Millner Portland State University, [email protected] Carl Abbott Portland State University, [email protected] Cathy Galbraith The Bosco-Milligan Foundation Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/black_studies_fac Part of the United States History Commons, and the Urban Studies and Planning Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Citation Details Millner, Darrell; Abbott, Carl; and Galbraith, Cathy, "Cornerstones of Community: Buildings of Portland's African American History" (1995). Black Studies Faculty Publications and Presentations. 60. https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/black_studies_fac/60 This Report is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Black Studies Faculty Publications and Presentations by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. ( CORNERSTONES OF COMMUNITY: BUILDINGS OF PORTLAND'S AFRICAN AMERICAN HISTORY Rutherford Home (1920) 833 NE Shaver Bosco-Milligan Foundation PO Box 14157 Portland, Oregon 97214 August 1995 CORNERSTONES OF COMMUNITY: BUILDINGS OF PORTLAND'S AFRICAN AMERICAN HISTORY Dedication This publication is dedicated to the Portland Chapter ofthe NMCP, and to the men and women whose individual histories make up the collective history ofPortland's -

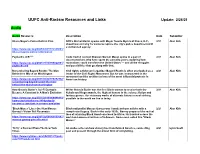

UUFC Anti-Racism Resources and Links Update: 2/28/21

UUFC Anti-Racism Resources and Links Update: 2/28/21 Audio Audio Resource Description Date Submitter Ithaca Mayor's Police Reform Plan NPR's Michel Martin speaks with Mayor Svante Myrick of Ithaca, N.Y., 2/21 Alan Kirk about how and why he wants to replace the city's police department with a civilian-led agency. https://www.npr.org/2021/02/27/972145001/ ithaca-mayors-police-reform-plan Payback's A B**** Code Switch co-host Shereen Marisol Meraji spoke to a pair of 2/21 Alan Kirk documentarians who have spent the past two years exploring how https://www.npr.org/2021/01/14/956822681/ reparations could transform the United States — and all the struggles paybacks-a-b and possibilities that go along with that. Remembering Bayard Rustin: The Man Civil rights activist and organizer Bayard Rustin is often overlooked as a 2/21 Alan Kirk Behind the March on Washington leader of the Civil Rights Movement. But he was instrumental in the movement and the architect of one of the most influential protests in https://www.npr.org/2021/02/22/970292302/ American history. remembering-bayard-rustin-the-man- behind-the-march-on-washington How Octavia Butler's Sci-Fi Dystopia Writer Octavia Butler was the first Black woman to receive both the 2/21 Alan Kirk Became A Constant In A Man's Evolution Nebula and Hugo awards, the highest honors in the science fiction and fantasy genres. Her visionary works of alternate futures reveal striking https://www.npr.org/2021/02/16/968498810/ parallels to the world we live in today.