Saber and Scroll Journal Volume V Issue III Special Issue Cowpens National Battlefield October 2016 Saber and Scroll Historical

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vol. 3 No. 1.1 ______January 2006

Vol. 3 No. 1.1 _____ ________________________________ _ __ January 2006 th Return to the Cow Pens! 225 Backyard Archaeology – ARCHH Up! The Archaeological Reconnaissance and Computerization of Hobkirk’s Hill (ARCHH) project has begun initial field operations on this built-over, urban battlefield in Camden, South Carolina. We are using the professional-amateur cooperative archaeology model, loosely based upon the successful BRAVO organization of New Jersey. We have identified an initial survey area and will only test properties within this initial survey area until we demonstrate artifact recoveries to any boundary. Metal detectorist director John Allison believes that this is at least two years' work. Since the battlefield is in well-landscaped yards and there are dozens of homeowners, we are only surveying areas with landowner permission and we will not be able to cover 100% of the land in the survey area. We have a neighborhood meeting planned to explain the archaeological survey project to the landowners. SCAR will provide project handouts and offer a walking battlefield tour for William T. Ranney’s masterpiece, painted in 1845, showing Hobkirk Hill neighbors and anyone else who wants to attend on the final cavalry hand-to-hand combat at Cowpens, hangs Sunday, January 29, 2006 at 3 pm. [Continued on p. 17.] in the South Carolina State House lobby. Most modern living historians believe that Ranney depicted the uniforms quite inaccurately. Lt. Col. Banastre Tarleton’s British Legion cavalry is thought to have been clothed in green tunics and Lt. Col. William Washington’s cavalry in white. The story of Washington’s trumpeter or waiter [Ball, Collin, Collins] shooting a legionnaire just in time as Washington’s sword broke is also not well substantiated or that he was a black youth as depicted. -

South Carolina Loyalists in the American Revolution South Carolina in 1776 (Adapted by R

South Carolina Loyalists in the American Revolution South Carolina in 1776 (adapted by R. S. Lambert from James Cook, 1773) Note: Broken lines, combined with natural features (e.g. rivers) delineate boundaries of judicial districts. Robert Stansbury Lambert Second Edition Works produced at Clemson University by the Center for Electronic and Digital Publishing, including Th e South Carolina Review and its themed series “Virginia Woolf International,” “Ireland in the Arts and Humanities,” and “James Dickey Revisited” may be found at our Web site: http://www.clemson.edu/caah/cedp. Contact the director at 864-656-5399 for information. Copyright 2010 by Clemson University ISBN 978-0-9842598-8-5 Second Edition CLEMSON UNIVERSITY DIGITAL PRESS Published by Clemson University Digital Press at the Center for Electronic and Digital Publishing, Clemson University, Clemson, South Carolina. Editorial Assistants: Christina Cook, Ashley Dannelly, Steve Johnson, Carrie Kolb Cover Design: Christina Cook Produced with the Adobe Creative Suite CS5 and Microsoft Word. Th is book is set in Adobe Garamond Pro and was printed by University Printing Services, Offi ce of Publica- tions and Promotional Services, Clemson University. To order copies, contact the Center for Electronic and Digital Publishing, Strode Tower, Box 340522, Clemson University, Clemson, South Carolina 29634-0522. To Edythe and Anne Contents Preface .......................................................................................................... viii Abbreviations and Acronyms ....................................................................... -

NATIONAL HISTORIC\LANDMARKS Network

NATIONAL HISTORIC\LANDMARKS Network Volume III, No. National Park Service, National Historic Landmarks Program Summer zooo Angel Island Immigration Station: Major Steps for Preserving a National Treasure Stewards by Daniel Quan by Mary L. Leach ROM 1910 TO 1940, ANGEL ISLAND Station was designated a National Historic Immigration Station, located in the Landmark in 1997. HE NATIONAL HISTORIC FSan Francisco Bay, was the primary The immigration station is part of Angel Landmark Stewards Association if entry for immigrants arriving on Island State Park, a unit of the California T (NHLSA) has taken the first the West Coast. Its most significant role Department of Parks and Recreation. The major steps in becoming a national organi was as a detainment center for Chinese movement to preserve and restore it has zation. Its Articles of Incorporation and its immigrants, who were subject to exclusion been led by the Angel Island Immigration Bylaws were recently filed in the ary immigration laws from 1882 until Station Foundation, a volunteer group that Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. In addi 1943. While detained, many Chinese successfully lobbied for $250,000 in state tion, its 501(c)(3) application for recogni immigrants carved poignant, emotional funds for initial stabilization of the deten tion as a charitable organization is being poems into the walls of the detention bar tion barracks, thereby allowing the building finalized for submission to the Internal racks. Over 100 poems have been docu to be opened to the public. Since then, no Revenue Service. In the meantime, the mented, many of which are still visible other public or private funds have been University of Maryland Foundation has today. -

National Register of Historic Places Continuation Sheet COLBURN HOUSE STATE HISTORIC SITE KENNEBEC COUNTY

rr r * { ' \ NPS Form 10-900 jv OMB No. 10024-0018 (Oct. 1990) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructionsTrts£tow to Complete/the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking VSn^he apj>ro0riate box or by entering the information requested. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable^" Fgf functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. PlacxNfdditional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property historic name Colburn House State Historic Site other names/site number 2. Location street & number Arnold Road. Old Route 27(.1 mi. south of northern intersection with Rt. 27) N/A not for publication city or town.............Pittston... N/A vicinity state Maine__________ code ME county Kennebec____ code 011___ zip code 04435 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this E nomination D request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In rny opinion, the property B meets Ddoes not meet the National Register criteria. -

Download Mapping the Battle of Cowpens Webquest

Tech For Intro Task Process Resources Eval Concl Support Teachers Introduction If I wasn’t for the Battle of Cowpens, we would probably all still be British citizens. Unfortunately, many Americans don’t know much about this battle that happened right in our back yard. They will likely never have a chance to visit and walk on the battlefield that was nothing more than a cattle pasture before January 17, 1781. But we all know that Gen. Daniel Morgan led the Patriots in this battle that was a turning point in the Revolution. Tech For Intro Task Process Resources Eval Concl Support Teachers Task You have been hired by the National Park Service to create an interactive map of the Battle of Cowpens. This map will show where all of the Patriot troops were lined up for the battle, who all of the different types of troops were, and who the leaders of each group were. The NPS has asked you to create this map to help Americans who will never get to come to Cowpens to have an idea of what happened in this key battle. Tech For Intro Task Process Resources Eval Concl Support Teachers Process 0 Step One – Research 0 Learn about the actual battle. Be sure to pay attention to how the different types of troops worked together. 0 Learn about the different troops – militia, Continentals, and dragoons or cavalry. How were they all different? 0 Learn about the leaders of each group 0 Gen. Daniel Morgan – commander of all troops 0 Andrew Pickens – commander of the militia 0 John Eager Howard – commander of the Continentals 0 William Washington – commander of the dragoons 0 Step Two – Create an interactive map 0 Be sure to include information about the different troops and their leaders where they lined up on the battlefield. -

Pownalbo Rough Court House the Lincoln County Cultural And

Form 10-300 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR STATE: (July 1969) NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Maine COUNTY: NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES Lincoln INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM FOR NPS USE ONLY ENTRY NUMBER (Type all entries — complete applicable sections) COMMON: /-^ . Pownalbo rough Courtt HoHouse AND/OR HISTORIC: STREET AND NUMBER: Cedar Grove Road CITY OR TOWN: Dresden COUNTY: X Maine 1 Lincoln CATEGORY ACCESS.BLE OWNERSH.P STATUS (Check One) TO THE PUBLIC D District |£] Building D P^lic Public Acquisition: H occupied seasonal [53 Restricted D Site Q] Structure S Private CD In Process D Unoccupied i — .n - • CD Unrestricted D Object D Both [ | Being Considered Lj Preservation work in progress n NO PRESENT USE (Check One or More as Appropriate) \ | Agricultural | | Government [~~1 Park CD Transportation | | Commercial 1 1 Industrial [~] Private Residence n Other (Specify) JC] Educational 1 1 Mi itary Q Religious I | Entertainment CD Museum J£] Scientific OWNER'S NAME: The Lincoln County Cultural and Historical Society STREET AND NUMBER: Federal Street Cl TY OR TOWN: CODE Wise as set Maine -T8- COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC: Lincoln County Courthouse Lincoln OUNTY: STREET AND NUMBER: CITY OR TOWN: Wiscasset Maine 1 8 TitI-E OF SURVEY: Historic American Buildings Survey DATE OF SURVEY: S Federal CD State | | County | | Loca DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS: Library of Congress STREET AND NUMBER: CITY OR TOWN: STATE: Washington D. C. 08 (Check One) [jjj| Excellent 1 Good CU Fair [~j Deteriorated a Ruins n Unexposed CONDITION (Check One) (Check One) D Altered E Unaltered D Moved [X) Original Site DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (if known) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The Plymouth Company Proprietors on April 13th, 1?61, voted to build, within the parade of Fort Shirley, a house forty-five feet long and foipty-four feet wide and three stories high, and that one room on the second story forty-five feet long and twenty feet wide be fitted with boxes and benches needful for holding courts. -

Hclassification

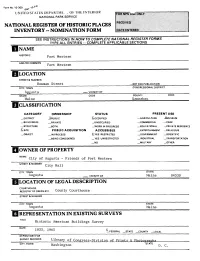

Form No. 10-300 ^ \0'1 ^ UNITED STATES DEPARTML. OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS______ I NAME HISTORIC Fort Western AND/OR COMMON Fort Western LOCATION STREET & NUMBER Bowman Street _NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Augusta VICINITY OF STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Maine Kennebec HCLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _D I STRICT -XPUBLIC ^.OCCUPIED _ AGRICULTURE _XMUSEUM _BUILDING(S) _PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE X_SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _IN PROCESS X.YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED — YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _NO —MILITARY —OTHER: OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME City of Augusta - Friends of Fort Western STREET* NUMBER CITY. TOWN STATE Augusta VICINITY OF Maine 04330 LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDS.ETC. County Courthouse STREET & NUMBER CITY, TOWN STATE Augusta Maine 1 REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Historic American Buildings Survey DATE 1933, 1965 X^-FEDERAL —STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Library of Congress-Division of Prints & Photographs CITY, TOWN Washington STATE D. C, DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED ^.ORIGINAL SITE X.GOOD _RUINS FALTERED _MOVED DATE. _FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBETHE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE As built in 1754, Fort Western was comprised of an oblonged-shaped log stockade about 160 by 62 feet with two two-story log blockhouses located at opposite corners of the palisade, with a large two-and-one-half story log Main Building located within its walls. -

The British Surrender Their Armies to General Washington After Their Defeat at Your Town in Virginia, Octorber 1781

Library of Congress Figure 1: The British surrender their Armies to General Washington after their defeat at Your Town in Virginia, Octorber 1781. 48 ARLINGTON 1-IISTORICA L MAGAZINE The Arlington House Engravings of the British Surrender at Yorktown: Too Often Overlooked? BY DEAN A. DEROSA In the morning room and in the second-floor hall ofArlington House, The Robert E. Lee Memorial (the US National Park Service historical site on the grounds ofArlington National Cemetery), hang two framed engravings, entitled "The British Surrendering their Arms to Gen. Washington after their Defeat at Yorktown in Virginia, October 1781." The two art pieces, first published in 1819, are drawn by John Francis Renault and engraved by Tanner, Vallance, Kearny & Co. The morning room engraving is in color, while the second floor engraving is inscribed in black ink (Figure 1). The caption at the base of the two engravings reads, "To the defenders of American independence, this print is most respectfully inscribed by their fellow citizen, Jn. Fcis. Renault, assistant secretary to the Count de Grass, and engineer to the French Army, at the siege of York." Thus, the twin engravings are drawn by a participant in the Siege of Yorktown, if not also a witness to the historic British surrender and subsequent surrender ceremony, which for all intents and purposes ended major hostilities during the American Revolution. The allegorical background of the engravings depicts not only the field upon which the British, Continental, and French armies stood during the sur render ceremony, but also a number of classical images and symbols of human discord, victory, and liberty, described in an 1804 prospectus apparently in reference to an early, circa 1810-1815 version of the Renault drawing (Figure 2) upon which the published engraving would eventually be based, that are largely lost upon us today. -

American Revolution Museum at Yorktown Grand Opening Celebration

AMERICAN REVOLUTION MUSEUM AT YORKTOWN GRAND OPENING CELEBRATION MARCH 23-APRIL 4, 2017, TO SALUTE 13 ORIGINAL STATES, FEATURE MUSEUM DEDICATION, PATRIOTIC CEREMONIES & MILITARY MUSIC YORKTOWN, Va., March 7, 2017 — Artillery salutes and flag-raising ceremonies. Fifes and drums and military dragoons. Brass bands and color guards. Historians, military veterans, re-enactors, entertainers and enthusiasts reveling in the Revolution will come together March 23 to April 4 to present 13 days of festivities showcasing the new American Revolution Museum at Yorktown. The Grand Opening Celebration of the American Revolution Museum at Yorktown will feature a patriotic salute to America’s 13 original states, a dedication ceremony on April 1, tours of expansive gallery exhibits, and military music and 18th-century interpretive experiences in the newly expanded Continental Army encampment and Revolution-era farm. The Grand Opening culminates the museum’s 10-year transformation from the Yorktown Victory Center. Through immersive indoor gallery exhibits with nearly 500 period artifacts, experiential films and interpretive living-history experiences, the American Revolution Museum at Yorktown presents a renewed national perspective on the meaning and impact of the Revolution. Ceremonies honoring the legacy of the first 13 states in the United States of America will take place each day in the order that they ratified the Constitution – Delaware, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Georgia, Connecticut, Massachusetts, Maryland, South Carolina, New Hampshire, Virginia, New York, North Carolina and Rhode Island. A dedication April 1 will officially launch the American Revolution Museum at Yorktown. Daily programs recognizing each state will begin midday with ceremonial welcoming remarks and presentation of the state flag, followed by an Honor Guard procession along the Grand Corridor to the outdoor re-created Continental Army encampment’s artillery amphitheater for a flag-raising ceremony and artillery salute. -

Banastre Tarleton QUICK FACTS

REVOLUTIONARYREVOLUTIONARY NEIGHBORSNEIGHBORS Banastre Tarleton QUICK FACTS • Member of the Regiment of Dragoon Guards (England’s finest calvary regiments) • Volunteered to fight in the American Revolutionary war under Lieutenant General Charles Lord Cornwallis • Engaged rebels near Ft. Lee, New Jersey • Captured Continental Army General Charles Lee in Basking Ridge, New Jersey • Was known for his brutal • Was defeated at the Battle of Cowpens in South Carolina • Authored a book about his experiences in the American Revolutionary War • Was made a Baronet in 1816 Banastre Tarleton • Died on January 16, 1833 1754-1833 Loyalist British Military Officer Author Visit us online today! www.revolutionarynj.org PAGE 1 REVOLUTIONARY NEIGHBORS Banastre Tarleton BIOGRAPHY I am perhaps the most feared and controversial few Sentrys down and saw their Position…We then British cavalry commander of the American retreated without any Loss or Wound except one Revolution. I am known for an important event Horses Ear.” Within the week, Tarleton would be that occurred here in New Jersey in the dark days of led over the Passaic River by local Loyalist Robert 1776. Drummond. I was born on August 21, 1754 in Liverpool, While Cornwallis, Harcourt and Tarleton England My father served as the Mayor of Liverpool were on Washington’s heels in his retreat across but also was a merchant, ship owner and slave trader. the state, 3,000 Continental troops under Major My family was wealthy and provided me many General Charles Lee crossed over from Westchester opportunities. I attended University College, Oxford on 2 December 1776, and were taking a more University, in London when my father passed away I southwesterly course, both avoiding the British and gained his inheritance but quickly spent it foolishly seemingly in little hurry to join Washington. -

The Cavalry at Cowpens: Thinking Inside the Box by Daniel Murphy

The Cavalry at Cowpens: Thinking Inside the Box By Daniel Murphy Recently I was asked to be the cavalry coordinator for the 225th anniversary reenactment of the Battle of Cowpens. I considered this an honor as for years Cowpens had always held a special significance for me; it was a turning point in the American Revolution, and one that was heavily influenced by the actions of the cavalry. And while I was thinking about how my fellow reenactors and I might carry out the mounted scenario, I began to see a number of wrinkles in the different theories regarding Lieutenant-Colonel William Washington and how he led the American cavalry. No reenactment can ever duplicate the exact movements of a battle and that was never my intent. But there were so many conflicting cavalry assesments in the otherwise excellent works on the battle that I started pouring over primary accounts of veterans, attempting to think “inside the box” and come up with a better understanding of what happened. Now before we go any further let me state right here that I do not hold a candle to the horsemen that took that field 225 years ago! They lived and fought from the saddle 24/7 where I’m lucky to just ride once or twice a week and make an occasional fox hunt or reenactment. Beyond fencing classes I have no formal arms training whatsoever. I personally have never seen modern combat and, like other reenanctors, the only thing I really know about 18th century warfare I either read in a book, heard around a campfire or attempted to recreate at an event. -

Confederate Wooden Gunboat Construction

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ScholarShip Confederate Wooden Gunboat Construction: Logistical Nightmare By Adam C. Edmonds May, 2011 Director of Thesis: Lawrence E. Babits, Ph.D. History Department The Confederate States Navy built wooden gunboats throughout the American Civil War. Within Civil War literature, more research and detailed analysis of Confederate States Navy construction focuses on building of ironclad vessels. Wooden gunboat construction is largely ignored. This thesis examines wooden gunboat construction in two different areas of the Confederacy: northeastern North Carolina in Washington and Elizabeth City, and the Mars Bluff Navy Yard in South Carolina. Before presenting two Confederate wooden gunboat construction case studies, a look at Confederate industrial, manufacturing, and transportation infrastructure, from the national perspective, brings into focus the logistical limitations station commanders faced in northeastern North Carolina and at Mars Bluff more clearly. Scattered, yet interdependent, marine manufacturing and ordnance facilities, connected by a suspect transportation network, created a logistical nightmare. Historical investigation into wooden gunboat construction in Washington, Elizabeth City, and Mars Bluff, examines an overlooked Confederate States Navy building program. CONFEDERATE WOODEN GUNBOAT CONSTRUCTION: LOGISTICAL NIGHTMARE A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History East Carolina University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Masters of Arts in History By Adam C. Edmonds May 2011 © Adam Edmonds, 2011 CONFEDERATE WOODEN GUNBOAT CONSTRUCTION: LOGISTICAL NIGHTMARE By Adam C. Edmonds APPROVED BY: DIRECTOR OF THESIS _________________________________________________ Lawrence E. Babits, Ph.D. COMMITTEE MEMBER _________________________________________________ Wade G. Dudley, Ph.D.