Cornelius J. Jaenen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aalseth Aaron Aarup Aasen Aasheim Abair Abanatha Abandschon Abarca Abarr Abate Abba Abbas Abbate Abbe Abbett Abbey Abbott Abbs

BUSCAPRONTA www.buscapronta.com ARQUIVO 35 DE PESQUISAS GENEALÓGICAS 306 PÁGINAS – MÉDIA DE 98.500 SOBRENOMES/OCORRÊNCIA Para pesquisar, utilize a ferramenta EDITAR/LOCALIZAR do WORD. A cada vez que você clicar ENTER e aparecer o sobrenome pesquisado GRIFADO (FUNDO PRETO) corresponderá um endereço Internet correspondente que foi pesquisado por nossa equipe. Ao solicitar seus endereços de acesso Internet, informe o SOBRENOME PESQUISADO, o número do ARQUIVO BUSCAPRONTA DIV ou BUSCAPRONTA GEN correspondente e o número de vezes em que encontrou o SOBRENOME PESQUISADO. Número eventualmente existente à direita do sobrenome (e na mesma linha) indica número de pessoas com aquele sobrenome cujas informações genealógicas são apresentadas. O valor de cada endereço Internet solicitado está em nosso site www.buscapronta.com . Para dados especificamente de registros gerais pesquise nos arquivos BUSCAPRONTA DIV. ATENÇÃO: Quando pesquisar em nossos arquivos, ao digitar o sobrenome procurado, faça- o, sempre que julgar necessário, COM E SEM os acentos agudo, grave, circunflexo, crase, til e trema. Sobrenomes com (ç) cedilha, digite também somente com (c) ou com dois esses (ss). Sobrenomes com dois esses (ss), digite com somente um esse (s) e com (ç). (ZZ) digite, também (Z) e vice-versa. (LL) digite, também (L) e vice-versa. Van Wolfgang – pesquise Wolfgang (faça o mesmo com outros complementos: Van der, De la etc) Sobrenomes compostos ( Mendes Caldeira) pesquise separadamente: MENDES e depois CALDEIRA. Tendo dificuldade com caracter Ø HAMMERSHØY – pesquise HAMMERSH HØJBJERG – pesquise JBJERG BUSCAPRONTA não reproduz dados genealógicos das pessoas, sendo necessário acessar os documentos Internet correspondentes para obter tais dados e informações. DESEJAMOS PLENO SUCESSO EM SUA PESQUISA. -

Balancing Leisure, Community Ani) Cultural Traditions

BALANCING LEISURE, COMMUNITY ANI) CULTURAL TRADITIONS: SOUTH ASIAN ADOLESCENTS IN CANADA BY SUSAN CLAUDIA TIRONE A thesis presented to the University of Waterloo in fulfillment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Recreation and Leisure S tudies Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, 1997 @ Susan Claudia Tirone 1997 National Library Bibliothèque nationale I*l of canada du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographie Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395. nie Wellington MtawaON KIAON4 Wwa ON K1A ON4 Canada Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant a la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loau, distribute or sell reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/nlm, de reproduction sur papier ou sur foxmat électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fiom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or othemise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. The University of Waterloo requires the signatures of al1 persons using or photocopying this thesis. Please sign below. and give address and date. ... III Balancing Leisure, Community and Cultural Traditions: South Asian Adolescents in Canada As young people enter their teen years, attitudes and behaviors are shaped by the variety and complexity of their daily lives. -

Note Abstract

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 382 427 RC 020 085 RUTH(:.: Candline, Mary TITLE Stages of Learning: Building a Native Curriculum. Teachers' Guide, Student Activities--Part I, Research Unit--Part II. INSTITUTION Manitoba Dept. of Education and Training, Winnipeg. Literacy Office. PUB DATE [92] NOTE I38p. PUB TYPE Guides - Classroom Use - Instructional Materials (For Learner) (051) -- Guides - Classroom Use Teaching Guides (For Teacher) (052) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC06 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *American Indian Education; Biographies; *Canada Natives; Canadian Studies; *Civics; Curriculum; Elementary Secondary Education; Federal Indian Relationship; Foreign Countries; Instructional Materials; Interviews; Language Arts; Learning Activities; *Library Skills; Politics; Public Officials; Reading Materials; Research Papers (Students); *Research Skills; Research Tools; Sculpture; Student Research; Teaching Guides; Vocabulary Development; Writing Assignments IDENTIFIERS Crazy Horse; *Manitoba ABSTRACT This language arts curriculum developed for Native American students in Manitoba (Canada) consists of a teachers' guide, a student guide, and a research unit. The curriculum includes reading selections and learning activities appropriate for the different reading levels of both upper elementary and secondary students. The purpose of the unit is for students to develop skills in brainstorming, biography writing, letter writing, note taking, researching, interviewing, spelling, and vocabulary. Reading selections focus on Elijah Harper, an Ojibway Cree Indian who helped defeat the Meech Lake Accord, an amendment to Canada's Constitution proposed in 1987. The Meech Lake Accord would have transferred power from the federal government to provincial governments and would have failed to take into account the interests of Natives, women, and minorities. The curriculum also includes reading selections on the creation of the Aboriginal Justice Inquiry and on Crazy Horse. -

Canada Politics: Deception and Betrayal in the Conservative Party

Canada Politics: Deception and Betrayal in the Conservative Party The Global Research News Hour By Marjaleena Repo and Michael Welch Region: Canada Global Research, June 08, 2013 Theme: GLOBAL RESEARCH NEWS HOUR, History “This creature, the so-called Conservative Party, if it goes forward will be an illegitimate creation conceived in deception and born in betrayal.” [1]Progressive Conservative leadership candidate David Orchard, October 17, 2003 “They would do all kinds of things…Organizing meetings that didn’t happen or people would go to a delegate selection meeting and the address was a pawn shop in Regina so people stood at the street corner waiting for something and nobody came…There was a kind of planned confusion…by people who really wanted us to stay out, and I think these people were people who wanted the party to be taken over.” Orchard campaign manager and political advisor Marjaleena Repo — — LISTEN TO THE SHOW Length (59:31) Click to download the audio (MP3 format) This week’s programme looks back ten years to the Progressive Conservative Party of Canada’s leadership race of 2003 which turned out to be the party’s last before it merged with the rival Canadian Alliance, led by leader Stephen Harper. The current Conservative Party has been racked with accusations of scandal and corruption. At least three Canadian Senators, hand-picked by the Prime Minister, are having their housing and living expenses reviewed, two Conservative Members of Parliament are being taken to task for improper accounting of their election expenses, and a court case recently determined that “there was an orchestrated effort to suppress votes during the 2011 election campaign by a person with access to the CIMS database” which is “maintained and controlled by the CPC (Conservative Party of Canada)”. -

The Political Culture of Canada

CHAPTER 2 The Political Culture of Canada LEARNING OBJECTIVES By the end of this chapter you should be able to • Define the terms political culture, ideology, and cleavages. • Describe the main principles of each of the major ideologies in Canada. • Describe the ideological orientation of the main political parties in Canada. • Describe the major cleavages in Canadian politics. Introduction Canadian politics, like politics in other societies, is a public conflict over different conceptions of the good life. Canadians agree on some important matters (e.g., Canadians are overwhelmingly committed to the rule of law, democracy, equality, individual rights, and respect for minorities) and disagree on others. That Canadians share certain values represents a substantial consensus about how the political system should work. While Canadians generally agree on the rules of the game, they dis- agree—sometimes very strongly—on what laws and policies the government should adopt. Should governments spend more or less? Should taxes be lower or higher? Should governments build more prisons or more hospitals? Should we build more pipelines or fight climate change? Fortunately for students of politics, different conceptions of the good life are not random. The different views on what laws and policies are appropriate to realize the ideologies Specific bundles of good life coalesce into a few distinct groupings of ideas known as ideologies. These ideas about politics and the good ideologies have names that are familiar to you, such as liberalism, conservatism, and life, such as liberalism, conserva- (democratic) socialism, which are the principal ideologies in Canadian politics. More tism, and socialism. Ideologies radical ideologies, such as Marxism, communism, and fascism, are at best only mar- help people explain political ginally present in Canada. -

The Requisites of Leadership in the Modern House of Commons 1

Number 4 November 2001 CANADIAN STUDY OF PARLIAMENT GROUP HE EQUISITES OF EADERSHIP THE REQUISITES OF LEADERSHIP IN THE MODERN HOUSE OF COMMONS Paper by: Cristine de Clercy Department of Political Studies University of Saskatchewan Canadian Members of the Study of Parliament Executive Committee Group 2000-2001 The Canadian Study of President Parliament Group (CSPG) was created Leo Doyle with the object of bringing together all those with an interest in parliamentary Vice-President institutions and the legislative F. Leslie Seidle process, to promote understanding and to contribute to their reform and Past President improvement. Judy Cedar-Wilson The constitution of the Canadian Treasurer Study of Parliament Group makes Antonine Campbell provision for various activities, including the organization of conferences and Secretary seminars in Ottawa and elsewhere in James R. Robertson Canada, the preparation of articles and various publications, the Counsellors establishment of workshops, the Dianne Brydon promotion and organization of public William Cross discussions on parliamentary affairs, David Docherty participation in public affairs programs Jeff Heynen on radio and television, and the Tranquillo Marrocco sponsorship of other educational Louis Massicotte activities. Charles Robert Jennifer Smith Membership is open to all those interested in Canadian legislative institutions. Applications for membership and additional information concerning the Group should be addressed to the Secretariat, Canadian Study of Parliament Group, Box 660, West Block, Ottawa, Ontario, K1A 0A6. Tel: (613) 943-1228, Fax: (613) 995- 5357. INTRODUCTION This is the fourth paper in the Canadian Study of Parliament Groups Parliamentary Perspectives. First launched in 1998, the perspective series is intended as a vehicle for distributing both studies prepared by academics and the reflections of others who have a particular interest in these themes. -

A THREAT to LEADERSHIP: C.A.Dunning and Mackenzie King

S. Peter Regenstreif A THREAT TO LEADERSHIP: C.A.Dunning and Mackenzie King BY Now mE STORY of the Progressive revolt and its impact on the Canadian national party system during the 1920's is well documented and known. Various studies, from the pioneering effort of W. L. Morton1 over a decade ago to the second volume of the Mackenzie King official biography2 which has recently appeared, have dealt intensively with the social and economic bases of the movement, the attitudes of its leaders to the institutions and practices of national politics, and the behaviour of its representatives once they arrived in Ottawa. Particularly in biographical analyses, 3 a great deal of attention has also been given to the response of the established leaders and parties to this disrupting influence. It is clearly accepted that the roots of the subsequent multi-party situation in Canada can be traced directly to a specific strain of thought and action underlying the Progressivism of that era. At another level, however, the abatement of the Pro~ gressive tide and the manner of its dispersal by the end of the twenties form the basis for an important piece of Canadian political lore: it is the conventional wisdom that, in his masterful handling of the Progressives, Mackenzie King knew exactly where he was going and that, at all times, matters were under his complete control, much as if the other actors in the play were mere marionettes with King the manipu lator. His official biographers have demonstrated just how illusory this conception is and there is little to be added to their efforts on this score. -

From Next Best to World Class: the People and Events That Have

FROM NEXT BEST TO WORLD CLASS The People and Events That Have Shaped the Canada Deposit Insurance Corporation 1967–2017 C. Ian Kyer FROM NEXT BEST TO WORLD CLASS CDIC—Next Best to World Class.indb 1 02/10/2017 3:08:10 PM Other Historical Books by This Author A Thirty Years’ War: The Failed Public Private Partnership that Spurred the Creation of the Toronto Transit Commission, 1891–1921 (Osgoode Society and Irwin Law, Toronto, 2015) Lawyers, Families, and Businesses: A Social History of a Bay Street Law Firm, Faskens 1863–1963 (Osgoode Society and Irwin Law, Toronto, 2013) Damaging Winds: Rumours That Salieri Murdered Mozart Swirl in the Vienna of Beethoven and Schubert (historical novel published as an ebook through the National Arts Centre and the Canadian Opera Company, 2013) The Fiercest Debate: Cecil Wright, the Benchers, and Legal Education in Ontario, 1923–1957 (Osgoode Society and University of Toronto Press, Toronto, 1987) with Jerome Bickenbach CDIC—Next Best to World Class.indb 2 02/10/2017 3:08:10 PM FROM NEXT BEST TO WORLD CLASS The People and Events That Have Shaped the Canada Deposit Insurance Corporation 1967–2017 C. Ian Kyer CDIC—Next Best to World Class.indb 3 02/10/2017 3:08:10 PM Next Best to World Class: The People and Events That Have Shaped the Canada Deposit Insurance Corporation, 1967–2017 © Canada Deposit Insurance Corporation (CDIC), 2017 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior written permission of the publisher. -

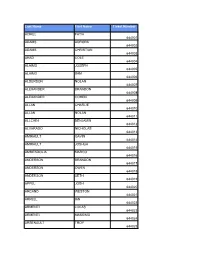

Last Name First Name Ticket Number ACIKEL FATIH 644001 ADAMS

Last Name First Name Ticket Number ACIKEL FATIH 644001 ADAMS AURORA 644002 ADAMS CHRISTIAN 644003 AHAD COLE 644004 ALAIMO JOSEPH 644005 ALAIMO SAM 644006 ALDERSON NOLAN 644007 ALEXANDER BRANDON 644008 ALEXANDER COHEN 644009 ALLAN CHARLIE 644010 ALLAN NOLAN 644011 ALLCHIN BENJAMIN 644012 ALVARADO NICHOLAS 644013 AMIRAULT GAVIN 644014 AMIRAULT JOSHUA 644015 AMMENDOLIA MARCO 644016 ANDERSON BRANDON 644017 ANDERSON OWEN 644018 ANDERSON SETH 644019 APPEL JOSH 644020 ARCAND WESTON 644021 ARKELL IAN 644022 ARMENTI LUCAS 644023 ARMENTI MASSIMO 644024 ARSENAULT TROY 644025 ASIS GRAYSON 644026 ASSELIN WYATT 644027 ATHERTON DATON 644028 AZEM SIMMONS BLAZE 644029 AZEM SIMMONS JADE 644030 AZEM SIMMONS KYLEN 644031 BACH AYDEN 644032 BAIOCCO MARIO 644033 BAIRD EVAN 644034 BAIRD LIAM 644035 BAIRD OWEN 644036 BAKER BENNETT 644037 BALL DANIEL 644038 BALL MATTHEW 644039 BANDERS LEO 644040 BANNISTER DYLAN 644041 BANNISTER LANDEN 644042 BARCHIESI BRYNN 644043 BARCHIESI SLOAN 644044 BARCLAY LONDON 644045 BARKER CHARLIE 644046 BARLOW HOLDEN 644047 BARNHARDT JAMES 644048 BARNHARDT WILLIAM 644049 BARRINGTON DYLAN 644050 BARRON LUCAS 644051 BARRY KELDON 644052 BARRY NOLAN 644053 BARRY TYSEN 644054 BARTON BROGAN 644055 BARTON NOLAN 644056 BASS-MELDRUM CALEB 644057 BAUGHMAN BRICE 644058 BAUGHMAN BRODY 644059 BEAMISH LEVI 644060 BEAMISH ZACK 644061 BEAUVAIS NOAH 644062 BEAVER BENJAMIN 644063 BEAVER JOSHUA 644064 BECK ERIC 644065 BELANGER BEAU 644066 BELANGER ETHAN 644067 BELFORD LINCOLN 644068 BENNETT COOPER 644069 BENSON JACK 644070 BERECZ MAX 644071 BERGEN CONNELL -

Orchard to Run for Tory Leadership

Orchard to run for Tory leadership By ALLISON DUNFIELD Globe and Mail Update Friday, January 17 – Online Edition, Posted at 4:52 PM EST Saskatchewan farmer and long-time Tory David Orchard Friday announced his intention to join the upcoming Progressive Conservative leadership race. Mr. Orchard, who had been expected to enter the race for some time, will officially announce his candidacy on Tuesday at a press conferences in Ottawa and Montreal. His bid raises the number of candidates to three. Of those, Tory MP Peter MacKay is the most well-known and is considered the front-runner. Mr. MacKay announced Thursday that he would run. Calgary lawyer Jim Prentice also launched his bid Thursday. A statement from Mr. Orchard's office says Mr. Orchard's campaign will focus on his commitment to the "historic principles of the Progressive Conservative Party and about how the renewal of national government based on those principles is essential to the preservation of our country and the values upon which it is based." Mr. Orchard, a free-trade opponent, came second to outgoing Progressive Conservative Leader Joe Clark at the 1998 leadership convention. At his early morning news conference in Nova Scotia Thursday, Mr. MacKay promised tax cuts and a political comeback to Tory party faithful. Both he and Mr. Prentice spoke of the need to bring more co-operation to Canada's right-wing parties, but Mr. Prentice said his intention is to first build the Tories and then do what he can to push forward notions of co-operation. The Progressive Conservatives had hoped to snag several high-profile candidates early on, including New Brunswick Premier Bernard Lord and Ontario businessman John Tory. -

Doing Business in Canada 2019

Doing Business in Canada A disciplined, team-driven approach focused squarely on the success of your business. Lawyers in offices across Canada, the United States, Europe and China — Toronto, Calgary, Vancouver, Montréal, Ottawa, New York, London and Beijing. Among the world’s most respected corporate law firms, with expertise in virtually every area of business law. When it comes to dealmaking, Blakes Means Business. Blakes Guide to Doing Business in Canada Doing Business in Canada is intended as an introductory summary. Specific advice should be sought in connection with particular transactions. If you have any questions with respect to Doing Business in Canada, please contact our Firm Chair, Brock Gibson by email at [email protected]. Blake, Cassels & Graydon LLP produces regular reports and special publications on Canadian legal developments. For further information about these reports and publications, please contact the Blakes Client Relations & Marketing Department at [email protected]. Contents I. Introduction ............................................................................................................... 1 II. Government and Legal System ............................................................................... 2 1. Brief Canadian History ............................................................................................. 2 2. Federal Government ................................................................................................. 3 3. Provincial and Territorial Governments -

Annual Report 2003 La De Annuel Rapport Rapport Annueldela 2003 Banque Ducanada

BANK OF CANADA OF CANADA BANK ANNUAL REPORT 2003 ANNUAL REPORT BANK OF CANADA ANNUAL REPORT 2003 2003 2003 BANQUE DU CANADA DU CANADA BANQUE BANQUE DU CANADA DU BANQUE LA DE ANNUEL RAPPORT RAPPORT ANNUEL DE LA RAPPORT Bank of Canada — 234 Wellington Street, Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0G9 5211 — CN ISSN 0067-3587 ISSN CN — 5211 0G9 K1A Ontario Ottawa, Street, Wellington 234 — Canada of Bank his many volunteer activities. His warm wit and generous spirit will be sorely missed. sorely be will spirit generous and wit warm His activities. volunteer many his Gerry Bouey and neither will his community to which he contributed to the very end through end very the to contributed he which to community his will neither and Bouey Gerry Those who worked with him over the course of his long and remarkable career will never forget never will career remarkable and long his of course the over him with worked who Those Achievement Award. In 1987, he was made a Companion of the Order of Canada. of Order the of Companion a made was he 1987, In Award. Achievement of Laws from Queen’s University. In 1983, he was presented with the Outstanding Public Service Public Outstanding the with presented was he 1983, In University. Queen’s from Laws of In 1981, he was made an Officer of the Order of Canada and also received an Honorary Doctor Honorary an received also and Canada of Order the of Officer an made was he 1981, In economic development and to the Bank’s growing international reputation.