Ceeb Ak Jën: Deconstructing Senegal's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Health Perspectives Among Senegalese Immigrants in Cincinnati, Ohio JASON HARTZ

STUDENT REPORTS Health Perspectives Among Senegalese Immigrants in Cincinnati, Ohio jASon hArtz over the past 30 years immi- diseases. Knowledge acquisition by gration from west Africa has way of the media, word of mouth, increased exponentially. For or lived experience has the ability to those migrating from Senegal to the alter personal decisions in relation United States, New York City was to health in diverse ways. For some the primary destination. From there immigrants the answer may be exer- communities have developed in cise, for others it may be through the other cities around the U.S., such as adoption of food avoidance strate- Cincinnati. The greater Cincinnati gies. For many of those Senegalese area, including the area of Kentucky in Cincinnati which I interviewed, just across the Ohio River, has seen it is apparent that an adherence to the development of a small, but shippers, and manufacturers, the a more “traditional” or “authentic” vibrant community of West Africans. owner of a small African market and Senegalese diet is the answer, no As a result of the influx of African the adjacent Senegalese restaurant, matter how global that diet may in migrants in the region, businesses who formerly worked for a global fact be. catering to their needs have also food distributer, has succeeded in developed. For the past decade in developing a business which caters Cincinnati, a small Africa-centric to the desires of not only the West food landscape has become visible. African community, but also Asian For the months of June and and Caribbean immigrant commu- July, 2011, I conducted research in nities. -

Field Anthropological Research for Context-Effective Risk Analysis Science in Traditional Cultures: the Case of Senegal

Frazzoli C. Field anthropological research for context-effective risk analysis science in traditional cultures: the case of Senegal. Journal of Global Health Reports. 2020;4:e2020043. doi:10.29392/001c.12922 Research Articles Field anthropological research for context-effective risk analysis science in traditional cultures: the case of Senegal Chiara Frazzoli 1 1 Department of Cardiovascular and Endocrine-Metabolic Diseases, and Ageing, Istituto Superiore di Sanità, Rome, Italy Keywords: senegal, ecology, toxicology, malnutrition, prevention, sub-sahara africa https://doi.org/10.29392/001c.12922 Journal of Global Health Reports Vol. 4, 2020 Background Nutritional homeostasis and health are increasingly affected by rapid nutrition transition, rapidly changing (food producing) environments and lifestyles, and increasing global formal and informal markets of consumer products. Toxicological risk factors are currently poorly focused in sub-Sahara Africa. Whereas important differences exist amongst countries, Senegal exemplifies the general trend. Focusing on Senegal, this orkw aims to build a translational framework for context-effective risk analysis science in traditional cultures by i) highlighting main aspects of eating and producing, with focus on savannah areas and pastoral systems, and analyzing their impact on socio-economic development, ii) analyzing people’s preparedness and proactivity, as well as channels and tools for prevention, and iii) discussing reasons of widespread demand of external education on diet and healthy foods. Methods Participant observation in field anthropological research ocusedf on food culture, consumer products and food systems in urban, semi-urban and rural settings. The system was stimulated with seminal messages on toxicological risk factors for healthy pregnancy and progeny’s healthy adulthood disseminated in counselling centres and women’s associations. -

Press Release

Press Release SOS SAHEL’s AFRICA DAYS CELEBRATE 40-YEARS OF ACHIEVEMENT & PREDICT A VIBRANT FUTURE FOR THE SAHELIAN REGION Dakar, Senegal, May 24, 2017……AS its 40th anniversary celebrations unfolded in Senegal this week , SOS Sahel was joined by a team of globally recognized experts in the international food security, nutrition and agricultural fields to deliver a powerful message of hope and opportunity to the region. While delivered in the country of its’ birth in 1976, SOS Sahel’s 40th birthday message was for Sahelian governments, farmers, communities, including importantly women and youth, as well as business leaders, across the region. Senegalese celebrities such as the King of New African Cuisine, Pierre Thiam, and renowned pianist, Cheick Tidiane Seck, backed the message of hope by demonstrating their magical gifts during SOS Sahel’s AFRICA DAYS (May 24-26). Since its’ creation by the visionary Senegalese President Léopold Sédar Senghor, as a response to the devastating droughts of the 1970s, SOS Sahel has delivered 450 projects and worked with over 1,000 Sahelian communities improving the lives, nutrition and livelihoods of millions of people across the region. SOS Sahel works with four million producers across the agricultural, livestock, fisheries and other productive sectors. Food Security & Nutrition Initiative 2025: SOS Sahel’s message of hope, captured under the banner of a four-year long “Food Security & Nutrition Initiative 2025”, is one of renewal and regeneration for the 11 countries of a region that will reach a population of 500 million by 2050. The newly launched SOS Sahel initiative, running from 2017-2020, aims to raise at least US4 million for SOS Sahel’s future work. -

42 Page Pdf Review Edition

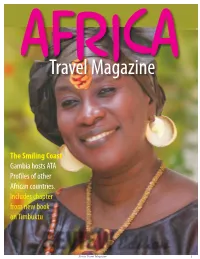

africa Travel Magazine The Smiling Coast Gambia hosts ATA Pro les of other African countries. Includes chapter from new book on Timbuktu Africa Travel Magazine 1 Photo by Karen Hoffman ATA IN REVIEW by Jerry W. Bird, Editor and Publisher This Yearbook Edition starts in Ban- jul, The Gambia at the Africa Travel Association 35th Annual Congress, where a new ATA President, Hon. Fatou Mass Jobe-Njie, (above) WDNHVRI¿FHDQGFRQFOXGHVZLWKD chapter from “To Timbuktu for a Haircut” by Rick Antonson. As Rick relates his present day journey through West Africa, he recalls the WULDOVDQGWULEXODWLRQVRI¿YHH[SORU- ers who came here between 1795 and 1855. The map on the opposite page traces the routes taken by Mungo Park, Robet Adams, Gordon Laing, Rene Caillie and Heinrich Barth. 2XUÀLJKWIURP-).,QWHUQDWLRQDO Airport in New York was a joy - thanks to Arik Airlines who treated our ATA media group with tender loving care. A special thanks to our host Bob Brunner, Arik’s North American manager. During an over- night stop in Lagos, Nigeria, we visited Arik headquarters and were (1) Editor at James Island, near Banjul, a remnant of the West African slave treated to dinner and an overnight trade. (2) New ATA President, Hon. Fatou Mass Jobe-Njie, The Gambia Minister VWD\DWWKH3URWHD+RWHO,NHMD of Tourism and Culture with Edward Bergman, ATA Executive Director. Gambia proved to be a gracious host. $7$GHOHJDWHVHQMR\HGUHOD[LQJ .LQWH'HOHJDWH cruises on the great river from and media group which the country’s name is and guest activi- derived. This brought to mind ties also included an initial goal of our two travel a trip to President magazines - the combination of -DPPHK¶VKRPH Air and Marine Tourism. -

Bronzeville Neighborhood Guide

Bronzeville Neighborhood Guide 3 Quick eats 8 7 4 1 Ain't She Sweet Cafe 7 J J Fish & Chicken 13 Union Submarine Shop 2920, 526 E 43rd St, 201 E 43rd St, 110 E 51st St, 27th Chicago, IL 60653 Chicago, IL 60653 Chicago, IL 60615 17 Sandwich & dessert shop Chicken wings & gyros 8 Checkers 16 11 2 Southtown Sub 5451 S Wentworth Ave, 14 Simply Soup 240 E 35th St, Chicago, IL 60609 Salad & Sandwiches Chicago, IL 60653 Burgers, fries & shakes 9 7 635 E 47th St, 15 Chicago/Pakistani sandwiches 6 9 Shore’s Xpress Chicago, IL 60653 2 35-Bronzeville-IIT 3851 S Michigan Ave, Fast and fresh food Sox-35th 3 3 Maggie Gyros & Chicken 3 10 1 2 349 E 47th St, Chicago, IL 60653 15 Culver’s Chicago, IL 60653 Fast food classics 3355 S Martin Luther King Dr, 10 Colossal Crab & Miller Chicago, IL 60616 4 4 Uncle J’s BBQ 1 1 9 502 E 47th St, Pizza Chicago ButterBurgers & Frozen Custard 5 Chicago, IL 60615 17 W 35th St, Chicago, IL 60616 Indiana Caribbean style BBQ Hand tossed pizzas 16 Ferro’s 1 200 W 31st St, 2 11 Chicago, IL 60616 12 2 5 5 Some Like It Black Creative Pier 31 1 43rd 6 Arts Bar 3101 S Lake Shore Dr, Beef, burgers, subs 810 E 43rd St, Chicago, IL 60616 Lake-front food & cocktails Chicago, IL 60653 17 Dim Dim dimsum and bakery 5 Organic restaurant 6 3 4 7 2820 S Wentworth Ave, 47th 4 14 12 Nicky's Gyros 47th 6 The Cajun Connoisseur Chicago, IL 60616 3 4240 S Wentworth Ave, 4317 S Cottage Grove Ave, Dim sum & baked goods Chicago, IL 60609 Chicago, IL 60653 Gyros and comfort food Cajun cuisine 13 8 2 1 Dining Bars Grocery stores Coffee 1 Pearl’s -

African Cuisine in Sidney?

Sidney-Shelby Economic Partnership presents... ISSUE 17 - WINTER 2016 Inside this Issue African Cuisine in Sidney? WORKFORCE MOBILE LAB On the road to provide workforce curricula to all the county schools... PAGE 2 NEW YOGA In 2015, Ousmane Wade opened most everything on the menu is grilled.” STUDIO Sene-Store at 549 North Vandemark Ousmane says that he likes to offer dishes OPENS IN Road in Sidney. Having spent the previous native to Senegal Africa along with others SIDNEY ten years working in Cincinnati at the more recognizable by Shelby County Classes available restaurant of his brother-in-law, Ousmane diners so in addition to Yassa and Maffe, for beginners to wanted to open a unique business of his guests can enjoy African fusion selections advanced own. The original concept for Sene-Store such as chicken wings, egg rolls, and students... was to offer grocery products common in quesadillas each prepared with the flavorful West Africa as the primary business and seasonings of Senegal. Those with a taste PAGE 2 feature African style cuisine as a secondary for spicy can have that too. Ousmane says focus. Ousmane understood that there he’s happy to season each order to the was a population of West African people taste preferences of his customers. A wide residing in Sidney and with they as his variety of domestic and import teas, juices, customer base, he could grow his business and soft drinks are also offered including REDSKIN from there. Kinkeliba and Bouye made fresh daily at PARK Over time the popularity of his UNDERWAY Senegalese/American fusion cuisine grew the restaurant. -

His Cover's Blown

2CHICAGO READER | DECEMBER 9,2005 | SECTION TWO The Business [email protected] His Cover’s Blown A Chicago cop’s prizewinning essay puts him in a league with Nobel and Pulitzer types. By Deanna Isaacs out,” he says. “But when the pain got worse, I decided it was appendicitis. I went to Saint Francis Hospital in the middle of the night and woke up ten days later.” It turned out that Calandra had a rare intestinal infection, complicated by blood clots—“The same thing Alan Alda had,” he says. “By my third sur- gery my chances for survival had shrunk to 10 percent.” Doctors removed 60 percent of his small intes- tine, which had atrophied, and he spent six weeks at Saint Francis, then two more weeks at Northwestern University’s Rehabilitation Institute. During that time members of the Chicago theater community and other friends rallied to his side, raising enough money to keep him going for six months without having to worry about finances. “Everybody put their hand on my back and helped push me up the mountain to get well again,” he says. “That white-light energy sur- rounded me, and I slowly started coming back.” By the following TIZ February, when the touring company . OR of Hairspray held Chicago auditions, Dale Calandra as Edna in Hairspray OS J Calandra was healthy enough to try CARL out. He joined the company in August Miscellany Martin Preib 2004, and “the rest is history,” he says. “I went from laying in a hospital bed You can’t get no Respect at the istrict 24 cop Martin Preib small-town newspaper near Detroit, Reincarnated as to—a year later—singing and dancing Chicago Center for the Performing says he’d rather his writing life a college English and classics major, across the country in a big red dress.” Arts anymore, but no one’s saying D stayed out of the spotlight. -

Value Chain 2- Onions

Senegal Value Chain Study: Onions Prepared for: RVO Netherlands Enterprise Agency Michiel Arnoldus Kerry Kyd Pierre Chapusette Floris van der Pol Barry Clausen Value Chain 2- Onions Senegal Value Chain Study 2 Preface A promising future in agriculture Senegal is expanding its food production with great ambition to serve consumers and increase rural welfare. Products of farmers in Senegal find their way to the local shops and soukhs and to export markets in the region and Europe. Some Dutch growers discovered Senegal long ago as the best place to make nutritious food of high quality with skilled and motivated farmers. The vicinity of Europe and the entry to the Sahel region makes this country an interesting shore to land. Agriculture in Senegal also has some challenges that need to be handled well, like water scarcity and soil salinity, quality improvement and post-harvest handling. Here Dutch expertise can help to improve the overall performance and sustainability of production and marketing by using modern technologies that make agriculture also fascinating for young professionals such as the use of quality seeds, precision agriculture, storage and packaging. This scoping study has analyzed those value chains of Senegalese agriculture where Dutch expertise and technology can have the most added value for better performance and solid positions in the consumer markets. It has also developed some tangible business cases for Dutch and Senegalese partners to cooperate and jointly make successful businesses. I thank the consultants of Sense for their excellent work. For more information or advice you can contact our agricultural experts through DAK- [email protected] The Agricultural Counselor of The Netherlands to Senegal Mr Niek Schelling Senegal Value Chain Study 3 Executive Summary Onion is a cornerstone of Senegalese cuisine. -

Manual Chapter - Cuisine (5 January 1993) H

•· I Manual Chapter - Cuisine (5 January 1993) H. cuisine cuisine is used to describe the culinary derivation of a food. H.1 Definition cuisine is characterized by dietary staples and foods typically consumed; specific ingredients in mixed dishes; types of fats, oils, seasonings, and sauces used; food preparation techniques and cooking methods; and dietary patterns. The culinary characteristics of population groups have developed and continue to develop over time. Cuisines have traditional names based primarily on geographic origin. A few cuisine names reflect ethnicity or other factors. Cuisines with several or multiple influences are listed in the hierarchy according to their major influence. Descriptors from this factor should be used primarily for prepared food products (e.g., entrees, desserts, cheeses, breads, sausages, and wines). Descriptors for cuisine should only be used if the cuisine can be easily determined from external evidence such as: the food name; a cuisine indication on a food label; the culinary identification of a restaurant, recipe, or cookbook; or the country of origin of the food, unless another cuisine is indicated. The indexer is not required to make a judgement about cuisine, nor is the indexer required to examine a food to determine its cuisine. Note that some food names have geographic descriptors that do not always identify a cuisine (e.g., Swiss cheese, Brussels sprouts). If in doubt, refer to the foods already indexed to determine whether the food name indicates a specific cuisine. The cuisine of foods may be important in establishing relationships of diet to health and disease. Cuisine provides information about a food from a cultural viewpoint and may assist in assist in more clearly identifying a food. -

The Africa Report, October 2015

72 DOSSIER AGRIBUSINESS Senegal gets Fertile and politically stable, hen Jean-Marie ded value. They really loved the Goudiaby stood product,” he says of the company Senegal is beginning to compete in a Waitrose that now distributes his onions. with Egypt and South Africa to supermarket in “It was new and original.” export fresh fruit and vegetables Britain in 2009 Goudiaby is part of a move- Wand sawhis test-runorganic sweet ment that is beginning to sweep to European markets. The onions for sale for £1 ($1.50) each, Senegal. Companies are position- government is also developing a it confirmed that his dream of ing themselves to be suppliers of becoming an exporter of high- fruit and vegetables to European major rice production centre quality niche vegetables from his markets. Ranging from small- around the Senegal River nativeSenegalcould become real- scale farms such as Goudiaby’s ity. “£1 is the price of one kilo of 50ha to the French-owned 300ha the same onions in Senegal,” he Grands Domaines du Sénégal By Rose Skelton in Saint-Louis says. “When you are exporting to farm, Senegal’s fertile land, good the European Union, the product climate, abundant reserves of wa- has to be innovative and have ad- ter and its proximity to Europe are THE AFRICA REPORT • N° 74 • OCTOBER 2015 Red onion producers in the Senegal River valley bag up their goods s growing ROSE SKELTON FOR TAR making it an economical and at- Goudiaby,whose sister Yolande across the flat landscape, Yolande tractive alternative to agriculture- does the manual work on part of and her sole helper digtrenches in exportingcountries such as Egypt, their 50ha parcel in the sandy thesandsothatwaterpumpedfrom Kenya and South Africa. -

Food Safety Programs and Academic Evidence in Senegal Food Safety Programs and Academic Evidence in Senegal October 2020

FEED THE FUTURE INNOVATION LAB FOR FOOD SAFETY (FSIL) Food Safety Programs and Academic Evidence in Senegal Food Safety Programs and Academic Evidence in Senegal October 2020 This report for the Feed the Future Innovation Lab for Food Safety is made possible by the generous support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The contents are the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government. Program activities are funded by USAID under Cooperative Agreement No. 7200AA19LE00003. Authors: Yurani Arias-Granada - Graduate Research Assistant, Department of Agricultural Economics, Purdue University Jonathan Bauchet - Associate Professor, Division of Consumer Science, Department of Hospitality and Tourism Management, Purdue University Jacob Ricker-Gilbert - Associate Professor, Department of Agricultural Economics, Purdue University Zachary Neuhofer - Graduate Research Assistant, Department of Agricultural Economics, Purdue University Table of Contents Acronyms 3 Executive Summary 4 1. Problem Statement 6 2. Review of the landscape of projects, interventions, and approaches currently taking place in Senegal to improve food safety 8 2.1. United States Agency for International Development (USAID)– Projects other than Innovation Labs 8 2.1.1. Senegal Dekkal Geej 9 2.1.2. Feed the Future Senegal Cultivating Nutrition (Kawolor) 9 2.1.3. Feed the Future Senegal Commercializing Horticulture (Nafoore Warsaaji) 9 2.1.4. Feed the Future Senegal Youth in Agriculture 9 2.1.5. Business Drivers for Food Safety 9 2.1.6. Other USAID engagements 10 2.2 USAID Feed the Future Innovation Labs 10 2.2.1. Feed the Future Innovation Lab for Food Processing and Post-Harvest Handling 10 2.2.2. -

Vol. 3: Senegal Sub-Saharan Report

Marubeni Research Institute 2016/09/02 Sub -Saharan Report Sub-Saharan Africa is one of the focal regions of Global Challenge 2015. These reports are by Mr. Kenshi Tsunemine, an expatriate employee working in Johannesburg with a view across the region. Vol. 3: Senegal September 10, 2014 Hello, everyone. In West Africa, the Ebola virus is spreading like wildfire and has become a tremendous concern. This time, as part of my Sub-Saharan Report series, I am going to introduce Senegal, which is located on the west end of the African continent. Many people may be more familiar with the name of the capital city Dakar than the name of the country because of the famous international motor sport rally raid (off- road race) which was formally called the Paris-Dakar (now The Dakar). The west side of Senegal faces the Atlantic Ocean and Dakar is located in Cape Verde, the westernmost point of Africa. Senegal has a diverse climate. The north side faces the Sahara Desert and has a dry climate. The middle of the country has a savanna-type climate with dry periods, while the southern part of the country has a tropical climate. When I visited Dakar this past July, it was the beginning of the rainy season and so it was not so humid (pictures 1 and 2). Pictures 1 and 2: The Atlantic Ocean from Cape Verde French is the official language of Senegal. Presently, about 95% of its citizens profess the Islamic faith, which spread there in the 11th century. From a religious sense, Senegal is not so strict; tourists can drink alcohol in hotels and restaurants, and women dress without necessarily having to be covered.