“Steeling the Gaze: Collaborative Curatorial Practices and Aboriginal Art” Zofia Krivdova a Thesis in the Department Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

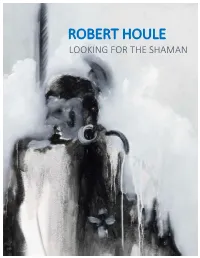

Aird Gallery Robert Houle

ROBERT HOULE LOOKING FOR THE SHAMAN CONTENTS INTRODUCTION by Carla Garnet ARTIST STATEMENT by Robert Houle ROBERT HOULE SELECTED WORKS A MOVEMENT TOWARDS SHAMAN by Elwood Jimmy INSTALL IMAGES PARTICIPANT BIOS LIST OF WORKS ABOUT THE JOHN B. AIRD GALLERY ROBERT HOULE CURRICULUM VITAE (LONG) PAMPHLET DESIGN BY ERIN STORUS INTRODUCTION BY CARLA GARNET The John B. Aird Gallery will present a reflects the artist's search for the shaman solo survey show of Robert Houle's within. The works included are united by artwork, titled Looking for the Shaman, their eXploration of the power of from June 12 to July 6, 2018. dreaming, a process by which the dreamer becomes familiar with their own Now in his seventh decade, Robert Houle symbolic unconscious terrain. Through is a seminal Canadian artist whose work these works, Houle explores the role that engages deeply with contemporary the shaman plays as healer and discourse, using strategies of interpreter of the spirit world. deconstruction and involving with the politics of recognition and disappearance The narrative of the Looking for the as a form of reframing. As a member of Shaman installation hinges not only upon Saulteaux First Nation, Houle has been an a lifetime of traversing a physical important champion for retaining and geography of streams, rivers, and lakes defining First Nations identity in Canada, that circumnavigate Canada’s northern with work exploring the role his language, coniferous and birch forests, marked by culture, and history play in defining his long, harsh winters and short, mosquito- response to cultural and institutional infested summers, but also upon histories. -

New Temporalities and Productive Tensions in Dana Claxton's Made to Be Ready a Review Essay

Survivance, Signs, and Media Art Histories: New Temporalities and Productive Tensions in Dana Claxton’s Made to Be Ready A Review Essay Julia Polyck-O’Neill Since our work documents records, and interprets decolonization, and is an expression of our cultures, our social relationships to the state and church, and our communities, what is the exchange with the viewer? One of pedagogy, understanding, truth, hope? Perhaps all and more. – Dana Claxton, “Re:Wind”1 arge-scale lightbox photographs and projections,2 reminiscent of Vancouver’s photo-conceptualistic narratives, dominate the darkened Simon Fraser University’s Audain Gallery. The eye Lmoves from static images to moving projections. The content of the images is visibly interconnected: the figure depicted in each appears to be the same woman; the punchy clarity, vivid palette, and the glossy, high definition and resolution as well as the contemporary aesthetic of the photographic images are also measurably consistent throughout. But although the works share an author, the theme, or intention, underlying them is challenging to discern. Although there are, ostensibly, referents available for issues of identity and remediation, they transcend the once traditional frameworks of conventional art historical categorization. The artist, Dana Claxton, is an artist-critic born in Yorkton, Saskatchewan, is of Hunkpapa Lakota descent, and is an associate professor in the University of British Columbia’s Art History, Visual Art, and Theory 1 Dana Claxton, “Re:Wind,” in Transference, Technology, Tradition: Native New Media, ed. Candice Hopkins, Melanie Townsend, Dana Claxton, Stephen Loft (Banff: Walter Phillips Gallery Editions, 2005), 16. 2 Claxton’s works are actually shown on LED fireboxes, a contemporary take on Jeff Wall and Ian Baxter’s fluorescent lightboxes of the late twentieth century. -

Ayapaahipiihk Naahkouhk

ILAJ YEARS/ANS parkscanada.gc.ca / parcscanada.gc.ca AYAPAAHIPIIHK NAAHKOUHK RESILIENCE RESISTANCE LU PORTRAY DU MICHIF MÉTIS ART l880 - 2011 Parks Parcs Canada Canada Canada RESILIENCE / RESISTANCE MÉTIS ART, 1880 - 2011 kc adams • jason baerg • maria beacham and eleanor beacham folster • christi belcourt bob boyer • marie grant breland • scott duffee - rosalie favell -Julie flett - Stephen foster david garneau • danis goulet • david hannan • rosalie laplante laroque - jim logan Caroline monnet • tannis nielsen • adeline pelletier dit racette • edward poitras • rick rivet BATOCHE NATIONAL HISTORIC SITE PARKS CANADA June 21 - September 15, 2011 Curated by: Sherry Farrell Racette BOB BOYER Dance of Life, Dance of Death, 1992 oil and acrylic on blanket, rawhide permanent collection of the Saskatchewan Arts Board RESILIENCE / RESISTANCE: METIS ART, 1880-2011 TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword 4 Aypaashpiihk, Naashkouhk: Lii Portray dii Michif 1880 - 2011 5 Curator's Statement 7 kcadams 8 jason baerg 9 maria beacham and eleanor beacham folster 10 christi belcourt 11 bob boyer 12 marie grant breland 13 scott duffee 14 rosaliefavell 15 Julie flett 16 Stephen foster 17 david garneau 18 danis goulet 19 david hannan 20 rosalie laplante laroque 21 jim logan 22 Caroline monnet 23 tannis nielsen 24 adeline pelletier dit racette 25 edward poitras 26 rick rivet 27 Notes 28 Works in the Exhibition 30 Credits 32 3 Resilience/Resistance gallery installation shot FOREWORD Batoche National Historic Site of Canada is proud to host RESILIENCE / RESISTANCE: MÉTIS ART, 1880-2011, the first Metis- specific exhibition since 1985. Funded by the Government of Canada, this is one of eighteen projects designed to help Métis com munities preserve and celebrate their history and culture as well as present their rich heritage to all Canadians. -

On Nature and Its Representation in Canadian Short Film and Video)

ON NATURE AND ITS REPRESENTATION IN CANADIAN SHORT FILM AND VIDEO) By JOSEPHINE M. MASSARELLA Integrated Studies Final Project Essay (MAIS 700) submitted to DR. MICHAEL GISMONDI in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts – Integrated Studies Athabasca, Alberta APRIL, 2015 ABSTRACT This essay examines representations of nature in a selection of short Canadian film and digital video. It discusses ontologically problematic (Hessing, “Fall” 288) aspects of nature, drawing largely on ecocinema and eco-aesthetics, as well as cinema studies, ecology, ecocriticism, ecoaesthetics, and (post)colonialism. Through these disciplines, it also explores the materiality of visual media and the impact of these media on the environment. Many of the difficulties such a project poses are exacerbated by the incipience of ecocinema, of which numerous and often contradictory interpretations exist. While such heterogeneity raises challenges for scholars wishing to isolate meaning, it provides a degree of versatility in the analysis of film and video. In this paper, several interpretations are brought to bear on a selection of short Canadian films, variously examined from within different critical paradigms. Keywords: interdisciplinary, ecophilosophy, systems of human domination, visual media On Nature and Its Representation 1 On Nature and its Representation in Canadian Short Independent Film and Digital Cinema The communicative power of moving images has long excited my creativity and fueled my professional life as a Canadian independent filmmaker. With this power I have conveyed personal perspectives that would otherwise remain silent and cultivated new ones that bring light to otherwise dusky regions of my mind. These perspectives often point towards nature, and look upon it with feelings of humility, reverence, and respect. -

RED WOMAN WHITE CUBE: FIRST NATIONS ART and Raclallzed SPACE

RED WOMAN WHITE CUBE: FIRST NATIONS ART AND RAClALlZED SPACE by Dana Lee Claxton PROJECT SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN LIBERAL STUDIES In the Liberal Studies Program of the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences O Dana Lee Claxton 2007 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Spring 2007 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author Approval Name: Dana Claxton Degree: Master of Liberal Studies Title of Project: Red Woman White Cube: First Nations Art and Racialized Space Examining Committee: Chair: Dr. Michael Fellman Senior Supervisor Professor of Liberal Studies Director. Graduate Liberal Studies Dr. Denise Oleksijczuk Supervisor Professor of Art School for Contemporary Arts Dr. Michelle LaFlamme External Examiner University of British Columbia English Department Date DefendedIApproved: +"+ SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY~ %?!%&@ ibra ry DECLARATION OF PARTIAL COPYRIGHT LICENCE The author, whose copyright is declared on the title page of this work, has granted to Simon Fraser University the right to lend this thesis, project or extended essay to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. The author has further granted permission to Simon Fraser University to keep or make a digital copy for use in its circulating collection (currently available to the public at the "Institutional Repository" link of the SFU Library website <www.lib.sfu.ca> at: ~http:llir.lib.sfu.calhandlell8921112~)and, without changing the content, to translate the thesislproject or extended essays, if technically possible, to any medium or format for the purpose of preservation of the digital work. -

Stop(The)G Ap: International Indigenous Art in Motion

Stop(the)Gap: International Indigenous art in motion Stop(the)Gap: International Indigenous art in motion Education Resource Acknowledgements Education Resource written by John neylon, art writer, curator and art museum/education consultant. The writer acknowledges the particular contribution of Brenda L Croft, Erica Green and Emma Epstein, and that of the Samstag Museum of Art staff, the participating artists and advisory curators. Published by the Anne & Gordon Samstag Museum of Art University of South Australia GPo Box 47, Adelaide SA 500 T 08 8300870 E [email protected] W unisa.edu.au/samstagmuseum Copyright © the author, artists, and University of South Australia All rights reserved. The publisher grants permission for this Education Resource to be reproduced and/or stored for twelve months in a retrieval system, transmitted by means electronic, mechanical, photocopying and/or recording only for education purposes and strictly in relation to the exhibition Stop(the)Gap: International Indigenous art in motion, at the Samstag Museum of Art. ISBn 978-0-980775-5-6 Samstag Museum of Art Director: Erica Green Curator: Exhibitions and Collections: Emma Epstein/Stephen Rainbird Coordinator: Scholarships and Communication: Rachael Elliott Samstag Administrator: Jane Wicks Helpmann Academy Intern: Lara Merrington Graphic Design: Sandra Elms Design Cover image: Warwick THORNTON, Stranded (detail), 0 film still, commissioned by Adelaide Film Festival Investment Fund 011, © the artist Stop(the)Gap: International Indigenous art in motion -

Renegotiating Identities, Cultures and Histories

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School January 2012 Renegotiating Identities, Cultures and Histories: Oppositional Looking in Shelley Niro's "This Land is Mime Land" Jennifer Danielle Mccall University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons, and the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Scholar Commons Citation Mccall, Jennifer Danielle, "Renegotiating Identities, Cultures and Histories: Oppositional Looking in Shelley Niro's "This Land is Mime Land"" (2012). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/4149 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Renegotiating Identities, Cultures and Histories: Oppositional Looking in Shelley Niro’s This Land is Mime Land By Jennifer McCall A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts School of Art and Art History College of the Arts University of South Florida Major Professor: Riccardo Marchi, Ph.D. Elisabeth Fraser, Ph.D. Sara Crawley, Ph.D. Date of Approval: February 28, 2012 Keywords: Contemporary art, Canada, photography, feminist, Native American Copyright © 2012, Jennifer McCall ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Dr. Riccardo Marchi, Dr. Elisabeth Fraser and Dr. Sara Crawley for all of their support and guidance over the past few years. Their knowledge inspired this project and their encouragement enabled me to carry it out. -

Indigenous Issues Have Come a Long Way on Campus— but There’S Still Much More to Do Held Back by Limited Resources, Dal Does What It Can

3 Editor’s note October 6–19, 2017 ISSUE 150–03 11 Dealing with your racist Uncle at Thanks- giving dinner 14 Indigenous art Indigenous issues have come a long way on campus— but there’s still much more to do Held back by limited resources, Dal does what it can ALEX ROSE, NEWS EDITOR Geri Musqua-LeBlanc has been an Elder-in-Residence at Dalhousie for less than two years, but already she has seen many changes for the better at the university. “Just from the faculty alone, their willingness to understand what reconcil- iation means and what they can do, how they can Indigenize their curriculum, their program,” she said, “to me, it’s positive.” The Elder-in-Residence program caters to the spiritual and emotional needs of Indigenous students. “However, we welcome students of all nations if they wish to come speak to an Elder,” Musqua-LeBlanc said. “Or a grandma, or a grandpa. Because grandmas and grandpas in Indigenous culture are very, very important. That’s where the young people get a lot of their support and encouragement.” CONT’D PG. 5 NORTH AMERICA’S OLDEST CAMPUS NEWSPAPER, EST. 1868 Letter from the editor Kaila Jefferd-Moore, editor-in-chief [email protected] The Gazette office is cozy with six people sitting in it staring at the chalkboard wall. Alex Rose, news editor Staff meetings often start this way: we spend a lot of time staring at our chalkboard— [email protected] it’s the blueprint of The Dalhousie Gazette sketched across our wall. Matt Stickland, opinions editor [email protected] Dates and random keywords we’ll use for SEO later, guide us through each meeting, Jessica Briand, arts & lifestyle editor helping plan out stories weeks in advance. -

Ontario Arts Foundation Annual Report 2019–2020

BUILDING A FOUNDATION FOR THE ARTS Ontario Arts Foundation Annual Report 2019–2020 2019–2020 From the Executive Director At the end of 2019, we felt strong. $3.3 million in The spring of 2020 also saw a heightened focus on contributions to new and existing funds had been social issues, with mass protests across the globe calling received. The Foundation assets grew to a record high for an end to systemic anti-Black racism that has created $87.8 million. One-year investment returns were a barriers and held people back from fully participating in strong 15%. Arts awards recognized some of Canada’s all parts of society. The Ontario Arts Foundation values finest artists and organizations benefited from the the contributions that Black, Indigenous and People of philanthropy of individual donors. What could go Colour make to the arts in Ontario. We are seeing more wrong? Little did we know that the world was about artists in leadership roles from diverse backgrounds in to change so dramatically with the advent of the many of Ontario’s arts organizations. We are grateful for COVID-19 pandemic. their perspective and new direction. Arts organizations have been particularly impacted, In all that has challenged the world in the last several with most having to cancel all programming for 2020, months, it is heartening to see that philanthropy is and the path is still unclear for 2021. Yet imagination still a core value of many Ontarians. We have seen and creativity are key to adapting to a new normal. the establishment of new funds that recognize the Artistic Directors are using these skills as they react contributions of past artistic leaders and look to create to the pandemic impact on arts programming and new opportunities for more diversified revenue streams. -

Two-Spirited People of Manitoba, Inc. College of Nursing

College of Nursing Two-Spirited People of Manitoba, Inc. • Social Determinants of Health are a group of social and • Societal stigma, colonized attitudes, and prejudice directed towards economic factors related to people’s place in society1. For some Two Indigenous people and sexual minorities. This may result in a lifetime Spirit people, they include ongoing effects of colonization; of harassment, discrimination and victimization4, 5. displacement from native lands, native lands, segregation in Indian • Isolation, exclusion and rejection by families, communities and Residential Schools, inadequate housing, the 60’s Scoop, and society prevents access to relevant health and social services. subsequent loss of family connections, language and culture. Homophobia and fear of violence pushes some Two-Spirit people • Two-Spirit people’s sources of strength namely their culture, away from their home communities6. languages, land rights, and opportunities for self-determination are • In the city environment, Two Spirit people may experience poverty, 2 compromised . homelessness, societal homophobia, racism from society and the • Resurgence of Two-Spirit identities, histories, and pride is a positive LGBTQ+ community8, 9, 15. 2 social determinant of health . • Overrepresentation of Two Spirit youth as street involved, homeless; • Two-Spirit people view health holistically; this considers physical, and having experienced childhood trauma10. psychological, social, and spiritual factors3. • Suicide rates of Two-Spirit people are hard to obtain. • Two-Spirit people may be part of the LGBTQ+ community but relate • 18.4% of Indigenous peoples have seriously considered suicide18. more to cultural identity within their Indigenous community. These increased suicide rates reflect a national crisis. • Some LGBTQ+ groups and Indigenous Nations may hold perceptions • First Nations youth are at risk for suicide, five to seven times higher where Two-Spirit people aren’t fully accepted in either group11. -

Steidl WWP SS18.Pdf

Steidl Spring/Summer 2018 3 Index Contents Artists/Editors Titles Adams, Shelby Lee 63 1968 99 Paris Reconnaissance 113 3 Editorial 81 Orhan Pamuk Balkon Adams, Bryan 93 200 m 123 Paris, Novembre 95 4 Index 85 Christer Strömholm Lido Adolph, Jörg 14-15 42nd Street, 1979 61 Park/Sleep 49 5 Contents 87 Guido MocaficoLeopold & Rudolf Blaschka, The Bailey, David 103-109 8 Minutes 107 Partida 51 6 How to contact us Marine Invertebrates Baltz, Lewis 159 Abandoned Moments 133 Pictures that Mark Can Do 105 Press enquiries 89 Timm Rautert Germans in Uniform Bolofo, Koto 135-139 Abstrakt 75 Pilgrim 121 How to contact our imprint partners 91 Sory Sanlé Volta Photo Burkhard, Balthasar 71 Andreas Gursky 69 Poolscapes 131 93 Bryan Adams Homeless Callahan, Harry 151 Asia Highway 167 Printing 137 95 Sze Tsung, Nicolás Leong Paris, Novembre Clay, Langdon 61 B, drawings of abstract forms 25 Proving Ground 169 DISTRIBUTION 97 Shelley Niro Cole, Ernest 157 Bailey’s Democracy 104 Reconstruction. Shibuya, 2014–2017 19 99 Robert Lebeck 1968 7 Germany, Austria, Switzerland Collins, Hannah 149 Bailey’s East End 108 Regard 127 101 Andy Summers The Bones of Chuang Tzu 8 USA and Canada Davidson, Bruce 165 Bailey’s Naga Hills 109 Seeing the Unseen 153 103 David Bailey’s 80th Birthday 9 France Devlin, Lucinda 147 Balkon 81 Shelley Niro 97 104 David Bailey Bailey’s Democracy All other territories Dine, Jim 113 Ballet 145 Stories 5–7, Soweto—Dukathole—Johannesburg David Bailey Havana Edgerton, Harold 153 Balthasar Burkhard 71 129 105 David Bailey NY JS DB 62 11 Steidl Bookshops Eggleston, William 37-41 Binding 139 Structures of Dominion and Democracy 73 David Bailey Pictures that Mark Can Do 13 Book Awards 2017 Elgort, Arthur 145 Bones of Chuang Tzu, The 101 Synchrony and Diachrony, Photographs of the 106 David Bailey Is That So Kid Fougeron, Martine 119 Book of Life, The 63 J. -

Shelley Niro 7 Pm

february . march 2006 611 main street winnipeg manitoba canada r3b 1e1 204.949-9490 [email protected] www.mawa.ca mawa international womens day lecturer shelley niro 7 pm . march 8 . cinematheque . 100 arthur st Lecture SHELLEY NIRO is a member of the Six Nations Reserve, an exhibit re-looking at the works of the Group of Mohawk, Turtle Clan. Niro graduated from the Seven; The Journey, a solo exhibition at the CN Ontario College of Art and received her MFA from the Gorman Museum, University of California, Davis; a two University of Western Ontario. Her art practice includes person exhibit, Affinities, with artist Rebecca Belmore, at painting, photography, filmmaking and beadwork. the MacKenzie Art Gallery, Regina, Saskatchewan. Recent exhibitions include a group show at the Niro has just finished producing a 60-minute film, Cambridge Library and Art Gallery titled G7 Revisited, Suite: Indian. register for studio visits Inspired by what is around her, Shelley Niro usually mawa studio visits works form a domestic point of view. The Grand thursday march 9 River is a source for her work, as well as cultural For further information or to register contact MAWA history, personal history. She is stimulated by the at 949-9490 , 2004. Photo courtesy of the artist. energy that surges through her when she focuses urban shaman gallery on these elements. studio visits Ghosts Shelley Niro will visit your studio to discuss your friday march 10 work with you. There is no fee for this program but For further information or to register contact early registration is recommended.