THE LAKELAND of LANCASHIRE. No. III. the Two CONISTONS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

7. Industrial and Modern Resource

Chapter 7: Industrial Period Resource Assessment Chapter 7 The Industrial and Modern Period Resource Assessment by Robina McNeil and Richard Newman With contributions by Mark Brennand, Eleanor Casella, Bernard Champness, CBA North West Industrial Archaeology Panel, David Cranstone, Peter Davey, Chris Dunn, Andrew Fielding, David George, Elizabeth Huckerby, Christine Longworth, Ian Miller, Mike Morris, Michael Nevell, Caron Newman, North West Medieval Pottery Research Group, Sue Stallibrass, Ruth Hurst Vose, Kevin Wilde, Ian Whyte and Sarah Woodcock. Introduction Implicit in any archaeological study of this period is the need to balance the archaeological investigation The cultural developments of the 16th and 17th centu- of material culture with many other disciplines that ries laid the foundations for the radical changes to bear on our understanding of the recent past. The society and the environment that commenced in the wealth of archive and documentary sources available 18th century. The world’s first Industrial Revolution for constructing historical narratives in the Post- produced unprecedented social and environmental Medieval period offer rich opportunities for cross- change and North West England was at the epicentre disciplinary working. At the same time historical ar- of the resultant transformation. Foremost amongst chaeology is increasingly in the foreground of new these changes was a radical development of the com- theoretical approaches (Nevell 2006) that bring to- munications infrastructure, including wholly new gether economic and sociological analysis, anthropol- forms of transportation (Fig 7.1), the growth of exist- ogy and geography. ing manufacturing and trading towns and the crea- tion of new ones. The period saw the emergence of Environment Liverpool as an international port and trading me- tropolis, while Manchester grew as a powerhouse for The 18th to 20th centuries witnessed widespread innovation in production, manufacture and transpor- changes within the landscape of the North West, and tation. -

Colton Parish Plan 2003 Page 1 1.1

ColtonColton The results of a community consultation 2003 Parish Plan •Lakeside •Finsthwaite •Bouth •Oxen Park •Rusland •Nibthwaite ContentsContents 1. Foreword . .2 5. Summary of Survey Results . .28 - 30 by the Chairman of the Parish Council Analysis of the AHA report on the Questionnaire 2. Introduction and Policy . .3 6. Residents comments from questionnaire . .31 - 33 3. The Parish of Colton . .4 7. The Open Meetings Brief . .34 report on the three open meetings held and comments and points 4. Response from Organisations and Individuals . .5 raised at the meetings Information provided by various organisations Rusland & District W.I. .5 8. Action Plan . .35 - 37 Bouth W.I. .6 Young Farmers . .7-8 9. Vision for the Future . .38 Holy Trinity Parish Church Colton . .9 Saint Paul’s Parish Church, Rusland . .10 10. Colton Parish Councillors . .39 Tottlebank Baptist Church . .11 Rookhow Friends Meeting house in the Rusland Valley . .12 11. Appendix . .40 Finsthwaite Church . .13 Copy of the Parish Plan Questionnaire Response from Schools . .14 - 15 A Few of the Changes in Fifty Years of Farming . .16 - 17 National Park Authority owned properties in Colton Parish . .18 Response from the Lake District National Park Authority . .19 Response from Cumbria County Council . .19 South Lakeland District Council . .20 Rusland Valley Community Trust . .21 Forest Enterprise . .22 Hay Bridge Nature Reserve . .23 Lakeside & Finsthwaite Village Hall . .24 Rusland Reading Rooms . .25 Bouth Reading Rooms . .25 Oxen Park Reading Room . .25 Rusland Valley Horticultural Society . .26 - 27 Colton Parish Plan 2003 Page 1 1.1. ForewordForeword Colton Parish is one of the larger rural generally. -

1 Bulletin 77 – Summer 2018

Bulletin 77 – Summer 2018 Yanwath Hall, Eamont Bridge, Penrith © Mike Turner CVBG Chairman’s Chat – Peter Roebuck 2 CLHF Members News - Holme and District LHS, Cumbria Railways 3 Association Other News from Member Groups 7 Cumbria Archive News 9 Help Requested 11 Welcome to new CLHF Committee Member 13 CLHF Museum Visits 14 Cumbria County History Trust 16 Proposed New CLHF Consitution 18 Funding for Local History Societies 19 General Data Protection Regulations 20 Useful Websites 20 Events 21 Final Thoughts 24 1 www.clhf.org.uk Chairman’s Chat. The recent spell of glorious weather prompts thoughts about the impact of climate on history. The great threat to local communities before modern times was harvest failure. Crisis mortality rates were often the result, not just of outbreaks of deadly disease; and the two sometimes combined. Cattle droving was fundamentally affected by climate, only getting underway sometime from mid-April once grass growth removed the need to use hay as fodder. Bees have rarely had such a good start as this year to their foraging season, reminding us of the significance of honey as the major sweetener before sugar became widely used. Cane sugar was first grown by the Portuguese in Brazil during the 16th century but entered the British market from the Caribbean only from 1650. Not until well beyond 1700 was it cheap enough to rival honey. The numerous bee boles and other shelters for straw skeps (hives) in Cumbria pay tribute to the care with which bees were kept. Beekeeping was no mere pastime but an activity of considerable economic significance. -

Hydrological Data UK 1982

lii Hydrological data UK 1982 YEARBOOK INSTITUTE OF HYDROLOGY • BRITISH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY á 1 HYDROLOGICAL DATA UNITED KINGDOM 1982 YEARBOOK á HYDROLOGICAL DATA UNITED KINGDOM 1982 YEARBOOK An account of rainfall, river flows and groundwater levels January to December 1982 Institute of Hydrology British Geological Survey @ 1985 Natural Environment ResearchCouncil Published by the Institute of Hydrology, Wallingford, Oxon OX 10 8BB ISBN 0 948540 02 8 A note for buyers of the looseleafversion: So that this Yearbook can stand alone as a separatevolume, it has been necessaryto repeatmuch of the background information which has alreadyappeared in the 1981volume. Readersmay wish to savespace in the binder by discarding someof the repeatedpages e.g. 121to 142.Future editions will be planned to make this a simpler operation. Cover: Demonstrating the measurementof dischargeby the moving boat method on the River Exe during the IAHS Assembly at Exeter, July 1982. Photograph: M. Lowing HYDROLOGICAL DATA: 1982 FOREWORD In April 1982, care of the United Kingdom national archive of surface water data passed from the Department of the Environ- ment's Water Data Unit (which was disbanded) to the Institute of Hydrology (IH). In a similar move, the Institute of Geological Sciences, subsequently renamed the British Geological Survey (BGS), took over the national groundwater archive. Both IH and BGS are component bodies of the Natural Environment Research Council (NERC). The BGS hydrogeologists are located with at Wallingford and close cooperation between the two groups has led, among other things, to the decision to publish a single series of yearbooks and reports dealing with nationally archived surface and groundwater data and the use made of them. -

Index to Volume 10

INDEX TO VOLUME 10 VOLUME NUMBERS, PAGES AND DATES OF PUBLICATION For those who do not have Cumbrian Railways bound the page numbers for each issue of Volume 10 are as follows: Vol. Ser. Pages Date Vol. Ser. Pages Date No. No. No. No. 1 133 1-36 February 2010 7 139 201-236 August 2011 2 134 37-68 May 2010 8 140 237-272 October 2011 3 135 69-100 August 2010 9 141 273-308 February 2012 4 136 101-132 October 2010 10 142 309-348 May 2012 5 137 133-164 February 2011 11 143 349-388 August 2012 6 138 165-200 May 2011 12 144 389-436 October 2012 Accidents Mar - May 2010 95 Haverthwaite 187 Jun - Jul 2010 127 Furness, on the - Morning Chronicle, 1 Dec 1851 294 Aug - nov 2010 161 Penrith, Accident at, December 1903 286 Dec 2010 - Feb 2011 196 Gunpowder Van, haverthwaite 186 Mar - May 2011 230 Accommodation on the Ratty 306 Jun - Jul 2011 266 Advertisment - sandwith Quarries 293 Aug - oct 2011 296 Appleby east Nov 2011 - Feb 2012 342 BR station (ex-neR) 394 Mar - Apr 2012 383 NER station 395 Jun - Jul 2012 420 Appreciation, An Award for Barrow 155 Andrews, Michael 163 Background to building s&CR 36 Duff, Percy – MBE 282 Banktop station, Darlington 356 Machell, steven 67 Barrow Central Workings 129 Robinson, John 2 Barrow trip Workings 129 Sewell, John 67 Bart the engine no 92017 at Carlisle 66 Archive, note from Bashers, Gadgets and Mourners (skellon) (Book Review) 291 Letter from sir Wilfred Lawson 290 Belah Viaduct (Poem & Photo) 381 Arnside Viaduct opening Ceremony - FLAG newsletter 294 Big Locos on Cumbrian Coast Line 129 Around the Cumbrian -

Number in Series 10

THE JOURNAL OF THE Fell and Rock Climbing Club OF THE ENGLISH LAKE DISTRICT. VOL. 4. NOVEMBER, 1916. No. 1. LIST OF OFFICERS. President: W. P. HASKETT-SMITH. Vice-President: H. B. LYON. Honorary Editor of Journal : WILLIAM T. PALMER, Beechwood, Kendal. Honorary Treasurer : ALAN CRAIG, B.A.I., Monkmoors, Eskmeals, R.S.O., Cumberland. Hon. Assistant Treasurer : (To whom all Subscriptions should be paid) WILSON BUTLER, Glebelands, Broughton-in-Furness. Honorary Secretary : DARWIN LEIGHTON, Cliff Terrace, Kendal. Honorary Librarian: J. P. ROGERS. Members of the Committee : H. F. HUNTLEY. L. HARDY. J. COULTON. W. ALLSUP. G. H. CHARTER. DR. J. MASON. H. P. CAIN. Honorary Members t WILLIAM CECIL SLINGSBY, F.R.G.S. W. P. HASKETT-SMITH, M.A. CHARLES PILKINGTON, J.P. PROF. J. NORMAN COLLIE, PH.D., F.R.S. GEOFFREY HASTINGS. PROF. L. R. WILBERFORCE, M.A. GEORGE D. ABRAHAM. CANON H. D. RAWNSLEY, M.A. GEORGE B. BRYANT. REV. J. NELSON BURROWS, M.A. GODFREY A. SOLLY. HERMANN WOOLLEY, F.R.G.S. RULES. l.—The Club shall b* called " THE TELL AND ROCK CLIMBING CLUB OF THE BHGLISH LAKE DMTRICT," and its objects shall be to encourage rock-climbing and fell-walking in the Lake District, to serve as a bond of union for all lovers of mountain-climbing, to enable its members to meet together in order to participate in these forms of sport, to arrange for meetings, to provide books, maps, etc., at the various centres, and to give information and advice on matters pertaining to local mountaineering and rock-climbing. -

Supplemental Statement Washington, DC 20530 Pursuant to the Foreign Agents Registration Act of 1938, As Amended

Received by NSD/FARA Registration Unit 07/17/2013 12:53:25 PM OMB NO. 1124-0002; Expires February 28, 2014 «JJ.S. Department of Justice Supplemental Statement Washington, DC 20530 Pursuant to the Foreign Agents Registration Act of 1938, as amended For Six Month Period Ending 06/30/2013 (Insert date) I - REGISTRANT 1. (a) Name of Registrant (b) Registration No. Pakistan Tehreek e Insaf 5975 (c) Business Address(es) of Registrant 315 Maple street Richardson TX, 75081 Has there been a change in the information previously furnished in connection with the following? (a) If an individual: (1) Residence address(es) Yes Q No D (2) Citizenship Yes Q No Q (3) Occupation Yes • No D (b) If an organization: (1) Name Yes Q No H (2) Ownership or control Yes • No |x] - (3) Branch offices Yes D No 0 (c) Explain fully all changes, if any, indicated in Items (a) and (b) above. IF THE REGISTRANT IS AN INDIVIDUAL, OMIT RESPONSE TO ITEMS 3,4, AND 5(a). 3. If you have previously filed Exhibit C1, state whether any changes therein have occurred during this 6 month reporting period. Yes D No H If yes, have you filed an amendment to the Exhibit C? Yes • No D If no, please attach the required amendment. I The Exhibit C, for which no printed form is provided, consists of a true copy of the charter, articles of incorporation, association, and by laws of a registrant that is an organization. (A waiver of the requirement to file an Exhibit C may be obtained for good cause upon written application to the Assistant Attorney General, National Security Division, U.S. -

History of Holy Trinity, Colton

- HOLY TRINITY CHURCH COLTON NOTES ON ITS HISTORY AND ENVIRONS The parish of Colton lies in that part of Cumbria which was known as High Furness (now South Lakeland) and though it is not generally thought of as being part of the English Lake District, it is yet near enough to that enchanting region to share some of the magic of its renowned beauty. The sterner and wilder aspects of Nature - high mountains, difficult passes, deep lakes, raging and tumultuous water falls are not here; these lie farther North. A glimpse, however, of what we may expect there is suggested if from Colton we look across the beautiful valley of the Crake coming from Coniston Water, to that noble group of mountains which includes the Old Man, Dow Crag and Wetherlam. Though this scene is less majestic and awe-inspiring than the more famous Cumbrian views, yet its loveliness delights the eye and seems to link our Colton panorama with the beginning of the true Lake District. We have around us, in this parish of Colton, scenery of a charm and variety which provides perpetual wonder and joy. There are fine stretches of fell country across which streams and becks innumerable make their picturesque courses to the rivers Leven and Crake, adding 'the beauty born of murmuring sound' to their visual attractions. The scenery is far more diversified than that of Low Furness and it has a varied and irregular surface of cheerful valleys, rocky but modest acclivities and hanging woods everywhere, clothing their sides, almost to their summits. Colton Church is set in a scene of such wonderful beauty that anyone approaching it for the first time might be forgiven if he compared the apparent insignificance of man's handiwork with the striking loveliness of surrounding Nature. -

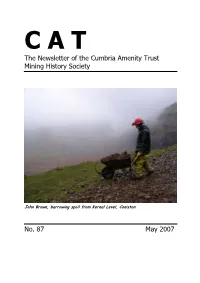

NEWSLETTER 087 May 2007

C A T The Newsletter of the Cumbria Amenity Trust Mining History Society John Brown, barrowing spoil from Kernal Level, Coniston No. 87 May 2007 Cumbria Amenity Trust Mining History Society Newsletter No 87, May 2007. Contents: Membership Page 2 News Editorial Page 2 Menbership Page 2 Obituary , Dr Ian Goodall Page 2 Newland Furnace Page 2 Library & Archive Page 3 CATMHS Journal Number Seven Page 3 Coniston Trail Guide Project Page 3 Mines Forum meeting, 2nd March 07 Page 4 Paddy End Survey Page 7 Purchase of GPS Survey equipment Page 7 OAN survey training Page 7 News from NAMHO Page 8 Mandall’s Office Page 11 Meets Greenside, 25th March Page 12 Kernal Level, Coniston Page 13 Small Artefact Competition Page 16 Middlecleugh second diary report Page 17 Articles Old photographs of Coniston copper mines Page 19 Old Man Days Page 20 The Gold Mines of Thames Page 22 Minutes CAT minutes, Page 37 Mystery picture – A response Inside back cover Society Officers and Committee Members Back cover Editorial These plans have been used by I’ve been complaining about the lack ourselves and our contractors as the of reporting of CAT meets and field starting point for all of the drawings activities, so I was delighted to receive required for our work since that date. twenty pages of reports for the last newsletter, which gave me problems Ian was well known and respected for fitting it all in! Well done everyone, his work on many historical Lake keep it up please. District buildings including Sizergh Castle, near Kendal. -

114363171.23.Pdf

ABs, l. 74. 'b\‘) UWBOto accompaiiy HAF BLACK’S PICTURES QBE GBIDE ENGLISH LAKES. BLACK’S TRAVELLING JVIAPS. REDUCED ORDNANCE MAP OF SCOTLAND. SCALE—TWO MILES TO THE INCH. 1. Edinburgh District (North Berwick to Stirling, and Kirkcaldy to Peebles). 2. Glasgow District (Coatbridge to Ardrishaig, and Lochgoilhead to Irvine). 3. Loch Lomond and Trossachs District (Dollar to Loch Long, and Loch Earn to Glasgow). 4. Central Perthshire District (Perth to Tyndrum, and Loch Tummel to Dunblane). 5. Perth and Dundee District (Glen Shee to Kinross, and Montrose to Pitlochry). 6. Aberdeen District (Aberdeen to Braemar, and Tomintoul to Brechin). 7. Upper Spey and Braemar District (Braemar to Glen Roy, and Nethy Bridge to Killiecrankie). 8. Caithness District (whole of Caithness and east portion of Sutherland). 9. Oban and Loch Awe District (Moor of Rannoch to Tober- mory, and Loch Eil to Arrochar). 10. Arran and Lower Clyde District (Ayr to Mull of Cantyre, and Millport to Girvan). 11. Peterhead and Banff District (Peterhead to Fochabers, and the Coast to Kintore). 12. Inverness and Nairn District (Fochabers to Strathpeffer, and Dornoch Firth to Grantown). In cloth case, 2s. 6d., or mounted on cloth, ^s. 6d. each. LARGE MAP OF SCOTLAND, IN 12 SHEETS. SCALE—FOUR MILES TO THE INCH. A complete set Mounted on Cloth, in box-case . .£180 Do. On Mahogany Boilers, Varnished . 2 2 0 Separate Sheets in case, 2s. 6d., or mounted on cloth, y. 6d. each. EDINBURGH : ADAM AND CHARLES BLACK. 5. aldy tod -och jch and J to % - I of re, id ol iUi'T-'I fe^0 it '■ 1M j lt 1 S i lii 1 Uni <■ qp-HV3. -

Colton Church Parish Newsletter, April 2020

PASTORAL LETTER 10 Bobbin Mill Spark Bridge ULVERSTON LA12 8 BS April 2020 Dear friends How do you want to be remembered? This thought was prompted by a report I saw in a newspaper. A woman had been murdered and the only thing the journalist could use to illustrate the woman’s life, her legacy as it were, was, ‘she had trained Princess Anne’s dogs’. I would like to think there were other glorious achievein so we can oiffer our thankments of her life more worthy of mention in that three-inch column report. Above the head of Jesus on the cross on Good Friday was a board on which was written ‘King of the Jews’. This epitaph was ordered by Pontius Pilate, not as a declaration but rather an insult to those who had brought Jesus before him for sentencing. As Jesus died on the cross He uttered a sentence which showed the depth of His Love for us and the depth of our need for that Love. He said, “Forgive them Father for they do not know what they are doing”. His subsequent Resurrection revealed the power of such God-given forgiveness. However, the Lord’s word from on the cross is not His last word. His last word has yet to be spoken: His judgement upon the earth and all who have lived thereon has yet to come. When He Jesus returns, at a time appointed but yet to be fulfilled, there will be a gathering of all who are living and have lived and died on earth. -

RCTS Library Book List

RCTS Library Book List Archive and Library Library Book List Column Descriptions Number RCTS Book Number Other Number Previous Library Number Title 1 Main Title of the Book Title 2 Subsiduary Title of the Book Author 1 First named author (Surname first) Author 2 Second named author (Surname first) Author 3 Third named author (Surname first) Publisher Publisher of the book Edition Number of the edition Year Year of Publication ISBN ISBN Number CLASS Classification - see next Tabs for deails of the classification system RCTS_Book_List_Website_09-12-20.xlsx 1 of 199 09/12/2020 RCTS Library Book List Number Title 1 Title 2 Author 1 Author 2 Author 3 Publisher Edition Year ISBN CLASS 351 Locomotive Stock of Main Line Companies of Great Britain as at 31 December 1934 Railway Obs Eds RCTS 1935 L18 353 Locomotive Stock of Main Line Companies of Great Britain as at 31 December 1935 Pollock D R Smith C White D E RCTS 1936 L18 355 Locomotive Stock of Main Line Companies of GB & Ireland as at 31 December 1936 Pollock D R Smith C & White D E Prentice K R RCTS 1937 L18 357 Locomotive Stock Book Appendix 1938 Pollock D R Smith C & White D E Prentice K R RCTS 1938 L18 359 Locomotive Stock Book 1939 Pollock D R Smith C & White D E Prentice K R RCTS 1938 L18 361 Locomotive Stock Alterations 1939-42 RO Editors RCTS 1943 L18 363 Locomotive Stock Book 1946 Pollock D R Smith C & White D E Proud Peter RCTS 1946 L18 365 Locomotive Stock Book Appendix 1947 Stock changes only.