Reading 3.2 Toby Miller, Geoffrey Lawrence, Jim Mckay and David

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

República Argentina - Poder Ejecutivo Nacional 2019 - Año De La Exportación

República Argentina - Poder Ejecutivo Nacional 2019 - Año de la Exportación Resolución Número: Referencia: EX-2018-29901019- -APN-DGD#MP - CONC. 1643 VISTO el Expediente N° EX-2018-29901019- -APN-DGD#MP, y CONSIDERANDO: Que, en las operaciones de concentración económica en las que intervengan empresas cuya envergadura determine que deban realizar la notificación prevista en el Artículo 9° de la Ley Nº 27.442, procede su presentación y tramitación por los obligados ante la ex COMISIÓN NACIONAL DE DEFENSA DE LA COMPETENCIA, organismo desconcentrado en el ámbito de la SECRETARÍA DE COMERCIO INTERIOR del MINISTERIO DE PRODUCCIÓN Y TRABAJO, en virtud de lo dispuesto y por la integración armónica de los Artículos 7° a 17 y 80 de dicha ley. Que la operación de concentración económica, se notificó el día 22 de junio de 2018, que se produce en el exterior generando efectos a nivel nacional, y consiste en la adquisición del control exclusivo de la firma AT&T INC., sobre la firma TIME WARNER INC., de acuerdo con el Contrato y el Plan de Fusión de fecha 22 de octubre de 2016. Que conforme a lo establecido en el Acuerdo de Fusión, la firma WEST MERGER SUB INC, una subsidiaria totalmente controlada por la firma AT&T INC., fue fusionada con y dentro de la firma TIME WARNER INC., siendo ésta última la empresa sobreviviente como una subsidiaria totalmente controlada por la firma AT&T INC. Que inmediatamente después, la firma TIME WARNER INC., se fusionó con y dentro de la firma WEST MERGER SUB II, LLC, y subsidiaria totalmente controlada por AT&T. -

The Commodification Process of Extreme Sports: The

THE COMMODIFICATION PROCESS OF uncertainty. He also defined the risk sports "as a variety of EXTREME SPORTS: THE DIFFUSION OF THE self-initiated activities that generally occur in natural X-GAMES BY ESPN environment settings and that, due to their always uncertain and potentially harmful nature, provide the opportunity for Chang Huh intense cognitive and affective involvement" (p. 53). The origin of using the word "extreme" in those activities goes Ph.D. Candidate in Park, Recreation, and Tourism back to the 1970s in France-when two Frenchmen referred Resources, Michigan State University, 172 Natural to their conquest of Chamonix couloirs as "ski extreme" Resources Building, East Lansing, MI 48824 (Youngblut, 1998). Youngblut described the word "extreme" as "far beyond the bounds of moderation; Byoung Kwan Lee exceeding what is considered reasonable; radical" (p. 24). Pedersen and Kelly (2000) contended that the term Ph.D. Candidate in Journalism and Communications, "extreme" was used in the context of sports to describe any University of Florida, 2096 Weimer Hall, Gainesville, FL sporting activity that was taken to "the edge." Then, they 32611 defined it as "a variety of sporting activities that have almost nothing in common except for high risk and an EuidongYoo appeal to females and males from the ages of 12_to_34" (p. 1). Synthesizing the definitions of Robinson and Pedersen Ph.D. Candidate in Physical Education, Florida State and Kelly, extreme sports are defined as a variety of University, Tallahassee, FL 32306 individual sporting activities that challenge against uncertain and harmful nature to achieve the enjoyment itself, especially, among the young generation. -

(Nueva) Guia Canales Cable Del Norte

Paquete Paquete Paquete Paquete Paquete Paquete Paquete Paquete Basico Premium Internac. Adultos XTIME HD Musicales PPV ●210‐Guatevision ●325‐NBC Sports ●1661‐History 2 HD Nacionales Variados ●211‐Senal Colombia ●330‐EuroSport Peliculas Educativos Pay Per View ●1671‐Sun Channel HD ●1‐TV Guia ●100‐Telemundo ●212‐Canal UNO ●331‐Baseball ●500‐HBO ●650‐Discovery ●800‐PPV Events ●2‐TeleAntillas ●101‐Telemundo ●213‐TeleCaribe ●332‐Basketball ●501‐HBO2 ●651‐Discovery Turbo ●810‐XTASY ●3‐Costa Norte ●103‐AzMundo ●214‐TRO ●333‐Golf TV ●502‐HBO LA ●652‐Discovery Science ●811‐Canal Adultos ●4‐CERTV ●104‐AzCorazon ●215‐Meridiano ●334‐Gol TV ●510‐CineMax ●653‐Civilization Disc. ●5‐Telemicro ●110‐Estrellas ●215‐Televen ●335‐NHL ●520‐Peliculas ●654‐Travel & Living High Definition ●6‐OLA TV ●111‐DTV ●216‐Tves ●336‐NFL ●530‐Peliculas ●655‐Home & Health ●1008‐El Mazo TV HD ●7‐Antena Latina ●112‐TV Novelas ●217‐Vive ●337‐Tennis Channel ●540‐Peliculas ●656‐Animal Planet ●1100‐Telemundo HD ●8‐El Mazo TV ●113‐Distrito Comedia ●218‐VTV ●338‐Horse Racing TV ●550‐Xtime ●657‐ID ●1103‐AzMundo HD ●9‐Color Vision ●114‐Antiestres TV ●220‐Globovision ●339‐F1 LA ●551‐Xtime 2 ●660‐History ●1104‐AzCorazon HD ●10‐GH TV ●115‐Ve Plus TV ●240‐Arirang TV ●552‐Xtime 3 ●661‐History 2 ●1129‐TeleXitos HD ●11‐Telesistema ●120‐Wapa Entretenimiento ●553‐Xtime Family ●665‐National Geo. ●1256‐NHK HD ●12‐JM TV ●121‐Wapa 2 Noticias ●400‐ABC ●554‐Xtime Comedy ●670‐Mas Chic ●1257‐France 24 HD ●13‐TeleCentro ●122‐Canal i ●250‐CNN ●401‐NBC ●555‐Xtime Action ●672‐Destinos TV ●1265‐RT ESP HD ●14‐OEPM TV ●123‐City TV ●251‐CNN (Es) ●402‐CBS ●556‐Xtime Horror ●673‐TV Agro ●1266‐RT USA HD ●15‐Digital 15 ●124‐PRTV ●252‐CNN Int. -

Challenging ESPN: How Fox Sports Can Play in ESPN's Arena

Challenging ESPN: How Fox Sports can play in ESPN’s Arena Kristopher M. Gundersen May 1, 2014 Professor Richard Linowes – Kogod School of Business University Honors Spring 2014 Gundersen 1 Abstract The purpose of this study is to explore the relationship ESPN has with the sports broadcasting industry. The study focuses on future prospects for the industry in relation to ESPN and its most prominent rival Fox Sports. It introduces significant players in the market aside from ESPN and Fox Sports and goes on to analyze the current industry conditions in the United States and abroad. To explore the future conditions for the market, the main method used was a SWOT analysis juxtaposing ESPN and Fox Sports. Ultimately, the study found that ESPN is primed to maintain its monopoly on the market for many years to come but Fox Sports is positioned well to compete with the industry behemoth down the road. In order to position itself alongside ESPN as a sports broadcasting power, Fox Sports needs to adjust its time horizon, improve its bids for broadcast rights, focus on the personalities of its shows, and partner with current popular athletes. Additionally, because Fox Sports has such a strong regional persona and presence outside of sports, it should leverage the relationship it has with those viewers to power its national network. Gundersen 2 Introduction The world of sports is a fast-paced and exciting one that attracts fanatics from all over. They are attracted to specific sports as a whole, teams within a sport, and traditions that go along with each sport. -

Sports Business Journal: Going Gray: Sports TV Viewers Skew Older Study: Nearly All Sports See Quick Rise in Average Age of TV

Sports Business Journal: Going gray: Sports TV viewers skew older Study: Nearly all sports see quick rise in average age of TV viewers as younger fans shift to digital platforms By John Lombardo & David Broughton, Staff Writers | Published June 5, 2017, Page 1 According to a striking study of Nielsen television viewership data of 25 sports, all but one have seen the median age of their TV viewers increase during the past decade. How top properties stack up Avg. age of Change TV viewers since Property in 2016 2006 PGA Tour 64 +5 ATP 61 +5 NASCAR 58 +9 MLB 57 +4 WTA 55 -8 NFL 50 +4 NHL 49 +7 NBA 42 +2 MLS 40 +1 Source: Magna Global The study, conducted exclusively for Sports Business Journal by Magna Global, looked at live, regular-season game coverage of major sports across both broadcast and cable television in 2000, 2006 and 2016. It showed that while the median age of viewers of most sports, except the WTA, NBA and MLS, is aging faster than the overall U.S. population, it is doing so at a slower pace than prime-time TV. The trends show the challenges facing leagues as they try to attract a younger audience and ensure long-term viability, and they reflect the changes in consumption patterns as young people shift their attention to digital platforms. “There is an increased interest in short-term things, like stats and quick highlights,” said Brian Hughes, senior vice president of audience intelligence and strategy at Magna Global. “That availability of information has naturally funneled some younger viewers away from TV.” Jeramie McPeek, former longtime digital media executive for the Phoenix Suns who now runs Jeramie McPeek Communications, a social media consultancy, also cited the movement of younger consumers to digital platforms. -

LED TV Installation Manual

LED TV Installation manual Thank you for purchasing Samsung product. To receive more service, please register your product at www.samsung.com/register Model Serial No. Figures and illustrations in this User Manual are provided for reference only and may differ from actual product appearance. Product design and specifications may be changed without notice. Introduction This TV B2B (Business to Business) model is designed for hotels or the other hospitality businesses, supports a variety of special functions, and lets you limit some user (guest) controls. Operational Modes This TV has two modes: Interactive and Stand-alone mode. y Interactive mode: In this mode, the TV communicates with and is fully or partially controlled by a connected Set Back Box (SBB) or Set Top Box (STB) provided by a hospitality SI (System Integration) vendor. When the TV is initially plugged in, it sends a command that attempts to identify the SSB or STB connected to it. If the TV identifies the SBB or STB and the SBB or STB identifies the TV, the TV gives full control to the SBB or STB. y Stand-alone mode: In this mode, this TV works alone without an external SBB or the STB. The TV has a Hotel (Hospitality) Menu that lets you easily set its various hospitality functions. Please see pages 26 to 30. The Menu also lets you activate or de-activate some TV and hospitality functions so you can create your optimal hospitality configuration. Still image warning Avoid displaying still images (such as jpeg picture files) or still image elements (such as TV channel logos, panorama or 4:3 format images, stock or news bars or crawls) on the screen. -

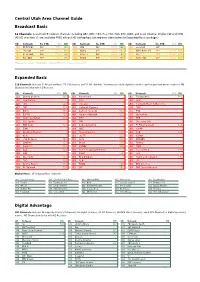

Central Utah Area Channel Guide Broadcast Basic

Central Utah Area Channel Guide Broadcast Basic 12 Channels: Local Utah Broadcast channels including ABC, NBC, CBS, Fox, PBS, PAX, BYU, KJZZ, and Local Channel 10 plus CW and UEN. (All HD channels {} are available FREE without HD set top box, but requires subscription to Expanded Basic package.) SD Network No STB DTV HD SD Network No STB DTV HD SD Network No STB DTV HD 102 KUTV CBS 02* {77-1} 502 106 ION 06* {81-13} 506 110 Local 10 10* 103 The CW 03* {81-3} 503 107 KUED 07* {80-3} 507 111 KMTI-Retro TV 11* {106-1} 511 104 KTVX ABC 04* {77-11} 504 108 BYU-TV 08* {106-2} 508 112 KJZZ 12* {79-13} 512 105 KSL NBC 05* {78-3} 505 109 KUEN 09* {80-13} 509 113 KSTU FOX 13* {79-3} 513 *Broadcast Basic customer without digital set-top box (STB) must use analog channels 02-13. Expanded Basic 120 Channels: Includes 12 Broadcast Basic, 55 SD Channels and 52 HD channels. You may also add a digital receiver to get the premium movie channels. HD Channels included with HD Receiver. SD Network DTV HD SD Network DTV HD SD Network DTV HD 114 Disney Channel 515 135 Paramount 162 Fox Business 562 115 New Nation 136 CMT 163 INSP 116 TBS 516 140 TV Land 164 Hallmark Movie & Mysteries 117 TNT 517 141 Hallmark Channel 170 FXM 118 ESPN 518 142 Cartoon Network 554 171 RFD 119 ESPN2 519 143 Outdoor Network 557 172 Sportsman 120 AT&T SportsNet 520 144 MTV 185 TBN 121 CBS Sports 145 VH1 186 Discovery Life 122 FOX News 522 146 Comedy Central 187 E! Entertainment 587 123 CNN 149 QVC 188 ESPNU 124 Weather Channel 150 Travel Channel 550 189 Golf 598 125 Nick 151 tru TV 551 190 CSPAN 126 USA Network 526 152 SyFy 552 191 OXYGEN 127 Lifetime 527 153 Bravo 553 192 History 128 Freeform 528 154 MSNBC 555 193 OWN 129 A&E 529 155 Home Shopping Network 194 Fox Sports 1 589 130 AMC 156 CNBC 556 195 FXX 131 Discovery 531 158 NFL Network 196 National Geographic 595 132 TLC 532 159 HLN 197 I.D. -

Nombre Señal Nueva Frecuencia

NOMBRE SEÑAL NUEVA FRECUENCIA On Demand 1 Canal de la Ciudad 7 Metro 8 América 9 Telefe 10 Tv Pública 11 El Trece 12 Canal 9 13 Todo Noticias 14 A 24 15 C5N 16 Crónica TV 17 26 TV 18 La Nación TV 19 Ciudad Magazine 20 NET TV 21 Encuentro 22 KZO 30 Diputados TV 36 Canal 90 - TyC Max - Senado TV 90 Deportv 100 T y C Sports 101 ESPN 102 ESPN 2 103 ESPN 3 104 ESPN + 105 Fox Sports 106 Fox Sports 2 107 Fox Sports 3 108 El Garage 109 The Golf Channel 110 NBA - Tv 111 Discovery Turbo 112 America Sports 115 Fox Sports Premium 123 TNT Sports 124 Paka Paka 200 Disney Channel 201 Nickelodeon 202 Cartoon Network 203 Disney XD 204 Discovery Kids 205 Boomerang 206 Disney Jr 207 Baby TV 208 Tooncast 209 Nick Jr 210 Natgeo Kids 211 HBO Este 250 HBO 2 251 HBO Plus Este 252 HBO Plus Oeste 253 Max Este 254 Max Up 255 Max Prime Este 256 Max Prime Oeste 257 HBO Family Este 258 HBO Signature 259 Fox Movies 260 Fox Series Este 261 Fox Series Oeste 262 Fox Action 263 Fox Family 264 Fox Comedy 265 Fox Cinema 266 Fox Classics 267 Incaa TV 300 Cinemax 301 FX Movies 302 Volver 303 Space 304 Cinecanal Este 305 TNT 306 TNT Series 307 FX 308 Fox 309 Sony 310 Warner Channel 311 Universal Channel 312 AXN 313 Studio Universal 314 A & E Mundo 315 Europa Europa 316 TBS 317 TCM 318 AMC 319 I-Sat 320 Atres Series 321 Syfy 322 Fox Life 323 Eurochannel 324 ID Investigacion Discovery 325 Comedy Central 326 Paramount 327 Pasiones 330 Telemundo 331 Lifetime 400 Gourmet.com 401 Food Network 403 E! Entertainment Television 404 Discovery Home & Health 405 Maschic 406 TLC 407 Hola TV 409 Glitz 410 INTI 411 Canal Rural 420 Viajar 421 Sun Channel 422 Telemax 423 Señal María (24 hs) 424 Nueva Imagen 425 EWTN 426 Canal 21 427 Wobi 428 Juegos APTIV 429 Juegos APTIV 430 National Geographic 450 Discovery Channel 451 Animal Planet 452 Discovery Theatre 453 The History Channel 454 TRU TV 455 Canal a 456 Film & Arts 457 History 2 458 Natgeo Wild 459 Discovery World 460 Discovery Civilization 461 Discovery Science 462 MTV 500 Quiero.. -

Canal Institucional *Hq Co | Canal Trece *Hd Co

CO | CABLE NOTICIAS *HD CL | CANAL 13 *FHD | Directo AR | AMERICA TV *HD | op2 AR | SENADO *HD CO | CANAL CAPITAL *HD CL | CANAL 13 CABLE *HD AR | C5N *HD AR | TELEFE *FHD CO | CANAL INSTITUCIONAL *HQ CL | CANAL 13 AR | C5N *HD | op2 AR | TELEFE *HD CO | CANAL TRECE *HD INTERNACIONACIONAL *HD AR | CANAL 21 *HD AR | TELEFE *HD CO | CANAL UNO *HD CL | CHV *HQ AR | CANAL 26 *HD AR | TELEMAX *HD CO | CANTINAZO *HD CL | CHV *HD AR | CANAL 26 NOTICIAS *HD AR | TELESUR *HD CO | CARACOL *HQ CL | CHV *FHD AR | CANAL 26 NOTICIAS *HD AR | TN *HD CO | CARACOL *HD CL | CHV *FHD | Directo AR | CANAL DE LA CIUDAD *HD AR | TV PUBLICA *FHD CO | CARACOL *FHD CL | LA RED *HQ AR | CANAL DE LA MUSICA AR | TV PUBLICA *HD CO | CARACOL 2 *FHD CL | LA RED *HD *HD AR | CINE AR *HD AR | AR | TV PUBLICA *HD | op2 CO | CARACOL INTERNACIONAL *HD CL | LA RED *FHD CINE AR *HD AR | TV5 *HD CO | CITY TV *HD CL | LA RED *FHD | Directo AR | CIUDAD MAGAZINE *HD AR | TVE *HD CO | COSMOVISION *HD CL | MEGA *HQ AR | CN23 *HD AR | VOLVER *HD CO | EL TIEMPO *HD CL | MEGA *HD AR | CN23 *HD AR | TELEFE INTERNACIONAL CO | LA KALLE *HD CL | MEGA *FHD AR | CONEXION *HD *HD A&E *FHD CO | NTN24 *HD CL | MEGA *HD | Op2 AR | CONSTRUIR *HD A3 SERIES *FHD CO | RCN *HQ CL | MEGA *FHD | Directo AR | CRONICA *HD AMC *FHD CO | RCN *HD CL | MEGA PLUS *FHD AR | CRONICA *HD ANTENA 3 *FHD CO | RCN *FHD CL | TVN *HQ AR | DEPORTV *HD AXN *FHD CO | RCN 2 *FHD CL | TVN *HD AR | EL NUEVE *HD CINECANAL *FHD CO | RCN NOVELAS *HD CL | TVN *FHD AR | EL NUEVE *FHD CINEMAX *FHD CO | RCN INTERNACIONAL CL | -

Optik TV Channel Listing Guide 2020

Optik TV ® Channel Guide Essentials Fort Grande Medicine Vancouver/ Kelowna/ Prince Dawson Victoria/ Campbell Essential Channels Call Sign Edmonton Lloydminster Red Deer Calgary Lethbridge Kamloops Quesnel Cranbrook McMurray Prairie Hat Whistler Vernon George Creek Nanaimo River ABC Seattle KOMODT 131 131 131 131 131 131 131 131 131 131 131 131 131 131 131 131 131 Alberta Assembly TV ABLEG 843 843 843 843 843 843 843 843 ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● AMI-audio* AMIPAUDIO 889 889 889 889 889 889 889 889 889 889 889 889 889 889 889 889 889 AMI-télé* AMITL 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 AMI-tv* AMIW 888 888 888 888 888 888 888 888 888 888 888 888 888 888 888 888 888 APTN (West)* ATPNP 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 — APTN HD* APTNHD 125 125 125 125 125 125 125 125 125 125 125 125 125 125 125 125 — BC Legislative TV* BCLEG — — — — — — — — 843 843 843 843 843 843 843 843 843 CBC Calgary* CBRTDT ● ● ● ● ● 100 100 100 ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● CBC Edmonton* CBXTDT 100 100 100 100 100 ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● CBC News Network CBNEWHD 800 800 800 800 800 800 800 800 800 800 800 800 800 800 800 800 800 CBC Vancouver* CBUTDT ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 CBS Seattle KIRODT 133 133 133 133 133 133 133 133 133 133 133 133 133 133 133 133 133 CHEK* CHEKDT — — — — — — — — 121 121 121 121 121 121 121 121 121 Citytv Calgary* CKALDT ● ● ● ● ● 106 106 106 ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● — Citytv Edmonton* CKEMDT 106 106 106 106 106 ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● — Citytv Vancouver* -

Unlocking the Smarter Remote Production Opportunity

A CONCISE GUIDE TO… UNLOCKING THE SMARTER REMOTE PRODUCTION OPPORTUNITY ive TV events, especially sports, create an unrivalledL buzz, anticipation and excitement among viewers the world over, but there are three major trends that the live production sector needs to recognize and address to ensure continued success. The rise in popularity of Subscription Video on Demand (SVOD) services is the first, underlining that consumers want more content – and more choice. The second is a greater focus on improved sustainability and employees’ wellbeing. Traditional live production set-ups require huge amounts of equipment and a large crew to be transported to the live location – not to mention several days’ worth of set up and take-down time. Finally, consumers are prepared to pay for fresh content, principally live sports. The trouble when it comes to live content – particularly sports – is that, as the cost of producing more live coverage is driven up by surging demand, it is not being met by the price that consumers are willing to pay. When you add in the rising outlay for hotly contested rights, the pressure is on broadcasters to find ways to produce more content more affordably – without compromising on quality. 1 GOING GLOBAL But all is not doom and gloom. The globalization of TV and rising viewer demand for more choices has unlocked huge potential, growing audiences and prospective revenues in new territories. For example, over the 2018/19 season, around 40 million viewers in North America watched English Premier League soccer (football in the rest of the world), within a global audience of 600 million people across 200 countries. -

06 SM 5/4 (TV Guide)

Page 6 THE NORTON TELEGRAM Tuesday, May 4, 2004 Monday Evening May 10, 2004 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 KHGI/ABC AWrinkle In Time Local Local Local Local KBSH/CBS Yes Dear Standing Raymond 2 1/2 Men CSI: Miami Local Late Show Late Late KSNK/NBC Fear Factor Las Vegas The Restaurant Local Local Local FOX The Swan Local Local Local Local Local Local Cable Channels A&E Biography Family Plots Airline Airline Third Watch Biography AMC The Breakfast Club Urban Cowboy ANIM World Gone Wild Cell Dogs Animal Precinct World Gone Wild Cell Dogs CNN Paula Zahn Now Larry King Live Newsnight Lou Dobbs Larry King Norton TV DISC Monster House Monster Garage American Chopper Monster House Monster Garage DISN Heavyweights Sis,Sis Boy Meets Kim Poss Proud Fa Evn Stvns Sis,Sis E! THS: Goldie & Kate E!ES Howard Stern Celebrities Uncensore ESPN NHL Semifinals Baseball T Sportscenter Outside Baseball T ESPN2 NHL Semifinals Baseball Fastbreak K Derby FAM Romy & Michele's High School Reunion Whose Lin Whose Lin The 700 Club Funniest Funniest FX Predator Cops Cops Predator HGTV Sm Desig Decor Ce Organize Dsgn Chal Dsgn Dim Dsgn Dme To Go Ground Sm Desig Decor Ce HIST Mail Call ColorOfW Band of Brothers Investigating History Cain & Able Mail Call ColorOfW LIFE Caught In The Act Caught in the Act Nanny Nanny MTV Primetime Players RW/RR Challenge Punk'D Pimp Ride Viva Video Clash Listings: NICK Dora Sabrina Full Hous Full Hous Cosby Cosby Roseanne Roseanne Cosby Cosby SCI Srargate SG-1 SPIKE Star Trek: TNG WWE Raw WWE Raw Zone 10 Things Every