An Evaluation of the Athletic Program in the Junior High Schools of Tucson, Arizona

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hearts Beat Strong

Volume 88. Number 11$1.00 PROSPECTWEDNESDAY, MOUNT OCTOBER 4, 2017 ******CARRTLOT 0039A**C071 MT PROSPECT PUBLIC LIBRARY 10 SEMERSON ST STE 1 MT PROSPECT. IL 60056-3295 000005,11,1 JOU . Dist. 57 Approves Budget Schools Plan For Deficit, Wait & See On Referendum By RICHARD MAYER Associate Editor Mount Prospect Elementary School Dist. 57 board members Thursday adopted this year's budget that carries a $2 million deficit. As a result, the district is using reserves to ensure the budget remains balanced. According to Assistant Supt. of Finance and Operations Adam Parisi, Dist. 57 originally anticipated reserves falling to 31% of total expenditures by June 30, 2018. That figure has since been adjusted to34%, or around $9.1 million, which isstill above the district's policy of keeping fund bal- Hearts Beat Strong For 'Love' ances between 30%-50% of Participants in the "Pink Lemonade 5K" benefitting Mount Prospect -based nonprofit Lemons of Love take off from the starting line of Sun- total expenditures with a target day's event at Lions Park. See more photos on page 9A. (Shawn Clisham/The Journal) of 40%. District officials still must figure out what to do for next budget season beginning July INSIDE 1, 2018, if a tax increase refer - (Continued on page 2A) Village Will Bury Centennial Time Capsule Oct. 14Page 2A Prospect Unites For Natural Disaster Victims The Prospect High School community do-said the club's co-sponsors, Maritza Rivera and nated nearly 380 cases of bottled water FridayAlain Ramirez. to hurricane and earthquake victims in Puerto Members of Knights United said after they Rico and Mexico. -

Mount Prospect Jomal

INSIDE Video Gaming A Win Collins To Lead MP, An Extra Helping For Some Local Towns Wheeling Chambers Of Speak Out! CRLOT 0041A**C071 Page 3A Page 12A Pages 15A, 14B MT PROSPECT PUBLIC LIBRARY 10 S EMERSON ST STE 1 MT PROSPECT, IL 60056-3295 0000114 MOUNTPROSPECT JOMAL Vol. 89 No. 36 Journal & Toptcs Media Group I journal-topics.com I Wednesday, September 4, 2019 I $1 `Not 0.714;$hp "4'11/oiii What We Expected' Experts On Hand To Describe City Prairie Issues, But Turnout Light By MC F. ANDERSON Journal & Topics Reporter Prospect Heights residents were reassured by experts and the city's Natural Resources Commission (NRC) that a local prairie will not cause coyote attacks, bees aren't being killed by herbicide and that progress on the prairie is still being made despite setbacks, but some residents were still displeased. The special town hall held by Aid. Wendy Morgan -Adams (3rd) and the NRC on Thursday,Aug . 22 was expected to be jam-packed, so when less than 20 people showed Labor Day Dip up, organizers were surprised. Local residents had one more chance to swim on a steamy Labor Day, Monday, Sept. 2, at Woodland Trails Pool in MountProspect. The "It's not what we expected," annual River Trails Park District Old Fashioned Family Picnic included many activities throughout the day including a pieeating contest and said NRC's Dana Sievertson to the rubber duck race. See more photos in next week's Journal. (Shawn Clisham/Journal photo) Journal in regard to the low turnout even with the experts brought in. -

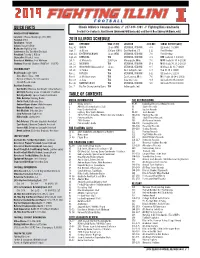

2019 Illinois Schedule Quick Facts Table of Contents

FOOTBALL QUICK FACTS Illinois Athletics Communication // 217-333-1391 // FightingIllini.com/media Football Co-Contacts: Kent Brown ([email protected]) and Derek Neal ([email protected]) UNIVERSITY INFORMATION Location: Urbana-Champaign (135,000) Founded: 1867 2019 ILLINOIS SCHEDULE Enrollment: 49,339 DATE OPPONENT TIME CT (TV) LOCATION 2018 REC SERIES HISTORY (LAST) Colors: Orange & Blue Aug. 31 AKRON 11 am (BTN) MEMORIAL STADIUM 4-8 ILL leads 1-0 (1996) Nickname: Fighting Illini Conference: Big Ten (West Division) Sept. 7 at UConn 2:30 pm (CBSS) East Hartford, CT 1-11 First Meeting President: Timothy L. Killeen Sept. 14 EASTERN MICHIGAN 11 am (BTN) MEMORIAL STADIUM 7-6 First Meeting Chancellor: Robert J. Jones Sept. 21 NEBRASKA TBA MEMORIAL STADIUM 4-8 NEB leads 12-3-1 (2018) Director of Athletics: Josh Whitman Oct. 5 at Minnesota 2:30/3 pm Minneapolis, Minn. 7-6 MINN leads 38-30-3 (2018) Stadium: Memorial Stadium (FieldTurf – 60,670) Oct. 12 MICHIGAN TBA MEMORIAL STADIUM 10-3 MICH leads 70-23-2 (2016) Oct. 19 WISCONSIN (Homecoming) 11 am MEMORIAL STADIUM 8-5 WIS leads 42-36-7 (2018) COACHING STAFF Oct. 26 at Purdue TBA West Lafayette, Ind. 6-7 Tied 44-44-6 (2018) Head Coach: Lovie Smith Nov. 2 RUTGERS TBA MEMORIAL STADIUM 1-11 ILL leads 3-2 (2018) Alma Mater: Tulsa, 1980 Nov. 9 at Michigan State TBA East Lansing, Mich. 7-6 MSU leads 26-18-2 (2016) Record at Illinois: 9-27 (3 seasons) Nov. 23 at Iowa TBA Iowa City, Iowa 9-4 ILL leads 38-34-2 (2018) Overall Record: same Nov. -

2005 FB Player Bios

TheThe PlayersPlayers Northern Illinois TB Garrett Wolfe (1) / Maxwell Award watch list (2005) 30 HuskiesHuskies AtAt AA GlanceGlance Northern Illinois University 2005 Football Overview The Basics The Personnel The Schedule (TV Games) Offense: One Back Team Captains (4): Sept. 3 at Michigan, 3:30 p.m. Defense: Attack Four-Three A.J. Harris, TB (6-1, 221, Sr.)-### (ABC Regional) Lettermen Returning: 36 Javan Lee, LB (6-2, 222, Sr.)-### Sept. 10 at Northwestern, 3 p.m. (Offense: 17 / Defense: 17 / Special Teams: 2) Ray Smith, SS (6-2, 185, Sr.)-### (ESPN Classic) Starters Returning: 15 Brian Van Acker, C (6-4, 287, Sr.)-## Sept. 17 Tennessee Tech, 3:05 p.m. (Offense: 7 / Defense: 6 / Special Teams: 2) (Comcast SportsNet Chicago) Lettermen Lost: 22 Returning Starters (15): Sept. 24 at Akron, 6 p.m.-% (Offense: 11 / Defense: 10 / Special Teams: 1) Offense (7): Oct. 5 Miami (OH), 6:35 p.m.-% Starters Lost: 11 Sam Hurd, SE (6-2, 187, Sr.)-###@ (ESPN2) (Offense: 5 / Defense: 5 / Starters: 1) Jake Nordin, TE (6-4, 253, Jr.)-# Oct. 15 Eastern Michigan, 3:05 p.m.-% Doug Free, OT (6-6, 290, Jr.)-##@ (Comcast SportsNet Chicago) Ben Lueck, OG (6-4, 310, Sr.)-## Oct. 22 at Kent State, 1 p.m.-% The Staff Brian Van Acker, C (6-4, 287, Sr.)-## Oct. 29 Ball State, 3:05 p.m.-% Head Coach: Garrett Wolfe, TB (5-7, 174, Jr.)-# (Comcast SportsNet Chicago) Joe Novak A.J. Harris, TB (6-1, 221, Sr.)-### Nov. 5at Central Michigan, 1 p.m.-% (Miami, OH, 1967) Nov. -

1995 Hall of Fame Inductees

2016 - 2017 Hall of Fame Inductees Chad Isaacson Class of 1992 All WSC Football Team – 1991 Ranked One of Top 50 Football Players in Illinois – 1991 Led DGN to 2nd Place in State in IHSA Football – 1991 Ranked One of Top 50 Baseball Players in Illinois – 1992 Led DGN Baseball Team to Regional Championship – 1991 Four Year Letter Winner at Southern Illinois in Baseball Coached DGN Baseball Team to IHSA Regional Championships – 2000, 2004, 2007, 2013, 2015 DuPage Area Baseball Coach of the Year - 2000 Coached DGN Baseball to IHSA Sectional Championship - 2004 Doug Rybar Class of 2009 Illinois Senior Gymnast of the Year - 2009 IHSA State Gymnastics All-Around Champion – 2009 IHSA State Gymnastics Ring Champion – 2009 Second in IHSA State Meet in Horizontal Bars – 2009 Second in IHSA State Meet in Pommel Horse – 2009 Third in IHSA State Meet in Horizontal Bars – 2007 Earned 16 IHSA medals at State Meets 2006-2009 Led DGN to WSC Conference Championship – 2009 WSC All – Around Champion – 2009 Earned 28 WSC Medals, 2006-2009 Earned 27 IHSA Sectional Medals 2006-2009 2016 Hall of Fame Inductees Garrett Edwards Class of 2006 First Team All- State Team – 2004 & 2005 All WSC Football Team – 2004 & 2005 Led the 2004 North Football Team to IHSA State Championship Rushed for over 1300 yards in 2004 & 2005 All WSC Basketball Team – 2005 & 2006 3 year letter winner in Football University of Illinois Second Team All – Big 10 Football – 2009 Defensive captain at University of Illinois – 2009 Member of the 2008 Rose Bowl Football Team at University of Illinois Tommy Edwards Class of 2004 First team All-State Football Team - 2003 All WSC Football Team – 2002 & 2003 Rushed for over 1000 yards in 2002 & 2003 Lead North Football Team to the WSC- Silver Conference Championship – 2003 DGN Football Team to the IHSA Final Four - 2003 All WSC Basketball Team – 2002 & 2003 All WSC Baseball Team – 2004 2016 Hall of Fame Inductees Burke Sims Class of 2009 IHSA State Swim Champion - 500 yd. -

Matters of Pride

LYONS TOWNSHIP HIGH SCHOOL MATTERS OF PRIDE 2020-2021 Congressional Debate Students took to Zoom and participated in six virtual tournaments. There was plenty of concern about Zoom fatigue with both practices and tournaments being virtual, but students used the technology to engage with teammates and students across the state in many important social, economic, and political issues of today. By February, the team was practicing in person and on Zoom, which propelled us to one of our best finishes ever at state; six of the LT competitors advanced ACADEMICS to the semifinal rounds (or 10% of all semifinalists). By year’s end, we had received 13 speaking awards and seven presiding officer awards. • Thirty-five National Merit Commended Students Cyberpatriots • Despite operating in full remote throughout a • Ten National Merit Semifinalists significantly modified season, CyberPatriots fielded two • Ten National Merit Finalists competition squads. In the equivalent of this year’s • One hundred ninety-eight LT seniors State Round, the Platinum Tier-qualifying team posted a were named Illinois State Scholars for 5th place finish, while the Gold Tier-qualifiers managed outstanding academic a 14th place finish among Illinois high schools. achievement. • Two team members were named Scholars in the 2021 National Cyber Scholarship Competition. They were each awarded a $2,500 scholarship for a college of their choice and free access to this summer’s Cyber Art Foundations Academy. • Four student-artists captured honors in the annual Chicago Area 4 X 5 Art Exhibit, with one 1st place winner and three Honorable Mentions. Family, Career & Community • Thirty-eight pieces of artwork created by student- Leaders of America artists were recognized in the Scholastic Art Awards Although the regional competition did not take competition. -

History of the West Suburban Conference

HISTORY OF THE WEST SUBURBAN CONFERENCE The West Suburban Conference is one of the strongest and most successful organizations of secondary schools in the state of Illinois in both the academic and athletic arenas. From its inception in 1924, the league has maintained a high degree of respect from its opponents because of its outstanding competitive nature. The West Suburban Conference is the fourth oldest Illinois League that is in existence today. Its roots go far beyond the period of formation of the original high school leagues at the turn of the century. The start of the conference is listed as January, 1924, with six charter members competing on only two conference-sponsored sports during that initial year. Back in the early 1910's, the precursor to the conference had early ties to what was known as the Cook County League. The last of their many re-organizational periods took place during this time, with the league reaching a total of twenty- three members; most being from the city of Chicago. At the end of the 1912-1913 school year, the league disbanded and many schools went to an independent status. The Suburban League was formed in September of 1913 with current WSC members Lyons Township, Morton, Oak Park-River Forest and Proviso being four of the original nine members. As these changes were taking place inside Cook Country, The Du Page County Athletic Association underwent its own re-alignment over the next ten years, The original league split into two new conferences in 1922; the Little Seven Conference and the Du Page Valley League. -

Where Excellence Is Tradition

Issue #6 | DECEMBER 2019 GLENBARD SOUTH Where Excellence Is Tradition 23W200 Butterfield Rd. Glen Ellyn, IL. 60137 Phone: (630)469-6500 Sharing and Caring Issue Visit our Website UPCOMING EVENTS December 4th : Holiday Concert December 7th: Breakfast with Santa December 11th: Band Holiday Concert December 18th-20th : Final Exams December 20 - End of 1st Semester December 23rd - January 5th: No School Winter Recess January 6: No School Institute Day Principal's Message We are just three weeks away from the end of the 1st semester. This is an important time to speak with your student(s) about finishing strong. Students and their parents should check our online gradebook, PowerSchool, to review current grades and any assignments that can still be accepted for credit. Additionally, Glenbard South offers a variety of student supports that students should take advantage of as they prepare for Final Exams. As 2019 comes to a close, we have an opportunity to reflect upon the strength and reputation of Glenbard South. More and more students consistently demonstrate their academic excellence on state and national levels through their hard work and commitment both in the classroom and through extracurricular competitions. On December 2nd at the Board of Education Academic Excellence Ceremony, we will have the pleasure to celebrate the academic achievements of the following students: National Merit Semifinalist: Michaela Reif National Merit Commended Students: William Coleman, Madeline Field, Ella McLaren and Tyler Meeks The Glenbard South administration and staff wish everyone a safe and happy winter break. We want to encourage our young drivers to use caution when driving, as more people will be traveling on roads. -

Table of Contents INTRODUCTION Table of Contents

Lyons Township High School District 204 2021-2022 Academic Program Guide Table of Contents INTRODUCTION Table of Contents .....................................................................................................................................................i-ii 2021-2022 Calendar .................................................................................................................................................. iii Mission Statement ......................................................................................................................................................iv LTHS District 204 Information ................................................................................................................................iv Four Year Academic Plan & Course Request Forms ........................................................................................v-xii DIRECTORIES District 204 Board of Education and Administrative Directory ..........................................................................1 Division/Department Chair Directories ..................................................................................................................2 Counselor and Social Worker Directories ...............................................................................................................3 TIMELINES 2021-2022 Course Registration Timelines ..............................................................................................................4 GENERAL INFORMATION Academic -

Student Handbook Includes All Glenbard West Rules and Guidelines As Well As School Policies and Procedures

2021 - 2022 CASTLE KEYS GLENBARD WEST HIGH SCHOOL Glenbard West High School Glenbard District Office 670 Crescent Blvd. 596 Crescent Blvd. Glen Ellyn, IL 60137 Glen Ellyn, IL 60137 Telephone (630) 469-8600 Telephone (630) 469-9100 Fax (630) 469-8615 Fax (630) 469-9107 www.glenbardwesths.org www.glenbard87.org SCHOOL ADMINISTRATION Dr. Peter Monaghan Principal Mr. Christopher Mitchell Assistant Principal, Student Services Ms. Stacy Scumaci Assistant Principal, Operations Dr. Rebecca Sulaver Assistant Principal, Instruction Mr. Joe Kain Assistant Principal, Athletics Mr. Jordan Poll Dean of Students Mr. Peter Baker Dean of Students Ms. Celeste Rodriguez Dean of Students BOARD OF EDUCATION Ms. Judith Weinstock, President Ms. Margaret DeLaRosa, Vice President Mr. Robert Friend, Parliamentarian Mr. Kermit Eby Mr. John Kenwood Ms. Martha Mueller Ms.Mireya Vera Dr. David Larson, Superintendent Table of Contents ATHLETICS A-42 Coaching Staff A-42 Interscholastic A-42 ATTENDANCE A-35 CONDUCT AND DISCIPLINE A-37 Behavior Intervention Assignment (B.I.A.) A-41 Bullying/Harassment/Intimidation A-38 Bus Conduct A-38 Detention A-41 Disciplinary Consequences A-40 Dress Code A-22 Extended Day Detention (E.D.D.) A-41 Electronic Devices A-31 Out of School Suspension A-41 Restorative Intervention Alternative (R.I.A.) A-41 Search & Seizure A-42 DISTRICT 87 INFORMATION AND BOARD A - 51 POLICIES SCHOOL COUNSELING SERVICES A-27 Counselor Assignments A-27 STUDENT ACTIVITIES A-43 HEALTH CENTER A-28 P.E. Medicals A-28 LIBRARY MEDIA DEPARTMENT A-29 Elliott Library -

20172018 HC Student Handbook.Pdf

DAILY SCHEDULE 8:00 a.m. – 8:50 a.m. Period 1 8:55 a.m. – 9:45 a.m. Period 2 9:50 a.m. – 10:40 a.m. Period 3 10:45 a.m. – 11:10 a.m. Period 4 Lunch 11:15 a.m. – 11:40 a.m. Period 5 Lunch 11:45 a.m. – 12:10 a.m. Period 6 Lunch 12:15 p.m. – 12:40 p.m. Period 7 Lunch 12:45 p.m. – 1:10 p.m. Period 8 Lunch 1:15 p.m. – 2:05 p.m. Period 9 2:10 p.m. – 3:00 p.m. Period 10 MONDAY LATE START SCHEDULE 8:50 a.m. – 9:30 a.m. Period 1 9:35 a.m. – 10:15 a.m. Period 2 10:20 a.m. – 11:00 a.m. Period 3 11:05 a.m. – 11:30 a.m. Period 4 Lunch 11:35 a.m. – 12:00 p.m. Period 5 Lunch 12:05 p.m. – 12:30 p.m. Period 6 Lunch 12:35 p.m. – 1:00 p.m. Period 7 Lunch 1:05 p.m. – 1:30 p.m. Period 8 Lunch 1:35 p.m. – 2:15 p.m. Period 9 2:20 p.m. – 3:00 p.m. Period 10 EARLY RELEASE SCHEDULE 8:00 a.m. - 8:25 a.m. Period 1 8:30 a.m. - 9:00 a.m. Period 2 9:05 a.m. - 9:30 a.m. Period 3 Periods 4 & 5 9:35 a.m. - 10:00 a.m. -

The Fighting Illini

THE FIGHTING ILLINI THE FIGHTING ILLINI 14 // FIGHTING ILLINI BASEBALL // FIGHTINGILLINI.COM // @ILLINIBASEBALL // #ILLINI THE FIGHTING ILLINI 2019 ROSTER NUMERICAL No. Name Pos. B/T Yr. Ht. Wt. Hometown Last School 2 Jimmy Burnette LHP L/L So. 6-1 195 Chicago, Ill. St. Laurence 3 Jack Yalowitz OF L/L Sr. 5-11 180 Chicago, Ill. Loyola Academy 4 Ben Troike SS R/R Jr. 5-10 170 Tinley Park, Ill. Lincoln-Way North 6 Michael Massey 2B L/R Jr. 6-0 190 Palos Park, Ill. Brother Rice 7 Ty Weber RHP R/R Jr. 6-4 215 Menomonee Falls, Wis. Menomonee Falls 8 Ryan Haff 1B/DH R/R R-Sr. 5-11 195 Oakbrook, Ill. Hinsdale Central 9 Jacob Campbell C R/R Fr. 6-0 205 Janesville, Wis. Janesville Craig 10 Josh Garner RHP R/R Jr. 6-2 210 Plainfield, Ill. Parkland College 12 Michael Michalak 1B/3B/OF R/R Sr. 6-3 180 Rochester, Minn. Des Moines Area CC 13 Ryan Schmitt RHP R/R Jr. 5-9 205 Hartland, Wis. Arrowhead 15 David Craan C R/R Sr. 6-0 180 Chicago, Ill. Whitney Young 16 Caleb Larson RHP R/R Fr. 6-3 180 Wheaton, Ill. Wheaton-Warrenville South 18 Kellen Sarver C/1B L/R R-Fr. 6-2 200 Champaign, Ill. Centennial 19 Ryan Kutt RHP R/R So. 6-3 195 Orland Park, Ill. Brother Rice 20 Branden Comia INF S/R Fr. 5-10 195 Orland Park, Ill. Carl Sandburg 21 Zak Devermann LHP L/L Sr.