Perspectives on Retail and Consumer Goods

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Slovenia Before the Elections

PERSPECTIVE Realignment of the party system – Slovenia before the elections ALEŠ MAVER AND UROŠ URBAS November 2011 The coalition government under Social Democrat Prime make people redundant. Nevertheless, the unemploy- Minister Borut Pahor lost the support it needed in Parlia- ment rate increased by 75 per cent to 107,000 over three ment and early elections had to be called for 4 Decem- years. This policy was financed by loans of 8 billion eu- ber, one year before completing its term of office. What ros, which doubled the public deficit. are the reasons for this development? Which parties are now seeking votes in the »political marketplace«? What However, Prime Minister Pahor overestimated his popu- coalitions are possible after 4 December? And what chal- larity in a situation in which everybody hoped that the lenges will the new government face? economic crisis would soon be over. The governing par- ties had completely different priorities: they were seek- ing economic rents; they could not resist the pressure of Why did the government of lobbies and made concessions; and they were too preoc- Prime Minister Borut Pahor fail? cupied with scandals and other affairs emerging from the ranks of the governing coalition. Although the governing coalition was homogeneously left-wing, it could not work together and registered no significant achievements. The next government will thus Electoral history and development be compelled to achieve something. Due to the deterio- of the party system rating economic situation – for 2012 1 per cent GDP growth, 1.3 per cent inflation, 8.4 per cent unemploy- Since the re-introduction of the multi-party system Slo- ment and a 5.3 per cent budget deficit are predicted – venia has held general elections in 1990, 1992, 1996, the goals will be economic. -

Rastislav Kulich Resume Dec 2010

RASTO KULICH, V Tunich 3, 120 00 Prague, Czech Republic, [email protected]; cell: +420 724 684 127 experience 2006- MCKINSEY & COMPANY PRAGUE, CZECH REPUBLIC (CR) present Senior engagement manager (Associate till Nov ‘08) Consistent top 20% performance rating Primary focus on strategic due diligences in consumer goods for private equity and strategic investors - 11 projects • Pet-food target in Netherlands, Germany and CEE, spirits in Turkey, food target in Ireland, FMCG target in Tanzania and Kenya, certification/testing target in France, frozen-food distribution in Poland and Czech, beverage target in Germany and Russia, online portal in Czech, due diligence guide for beverage client in UK, Internal Due Diligence Guide in Consumer Goods for McKinsey Europe Secondary focus sales & marketing – 10 projects including major pricing, commercial-excellence, lean and route-to- market projects in consumer-goods in Switzerland, South Africa, Czech, Poland, Russia • Created value estimated at $20 million via new route-to-market strategy for leading beverage client in Poland • Co-delivered profit increase of $25 million on European-wide pricing project for leading beverage client • Increased sales force productivity by 40% via commercial excellence project for pharmaceutical client in CR • Reduced number of calls in call center by 35% via addressing root cause in a lean project for energy company in CR 2006 - 2007 ERGONI.COM BOSTON, USA/MUMBAI, INDIA Co-founder • Co-founded internet startup built on mass-customization concept for luxury shirts -

2017 Food Retail Sectoral Report Retail Foods Philippines

THIS REPORT CONTAINS ASSESSMENTS OF COMMODITY AND TRADE ISSUES MADE BY USDA STAFF AND NOT NECESSARILY STATEMENTS OF OFFICIAL U.S. GOVERNMENT POLICY Required Report - public distribution Date: GAIN Report Number: 1724 Philippines Retail Foods 2017 Food Retail Sectoral Report Approved By: Ralph Bean Prepared By: Joycelyn Claridades-Rubio Report Highlights: The growing expansion and increase in sales of food retailers in the Philippines creates opportunities for more exports of U.S. high-value, consumer-oriented food and beverage products. Driven by a growing population, strong domestic consumption, and a buoyant economy, the food retail sector reached a growth of $45.3B in sales in 2016, a 4% increase from $43.5 in 2015. Post: Manila General Information: I. Overview of the Philippine Market The Philippines is the largest market in Southeast Asia for U.S. consumer-oriented food and beverage (f&b) products and one of the fastest growing markets in the world, importing $923.4 billion in U.S. f&b products in 2016. A mature market with growing demand for consumer-oriented products, the United States remains the Philippines’ largest supplier for food, beverage and ingredient products. Ranked as the 11th largest export market for U.S. high-value, consumer-oriented products, the Philippines imported $716.1 million from January through September 2017. Based on the chart below, the United States remains the largest supplier with fifteen percent (15%) market share, followed by China (9%), Indonesia and New Zealand (10%), and Thailand (8%). Total imports of consumer-oriented food grew annually by an average of 10%. Chart 1 – Market Share of Consumer-Oriented Products in the Philippines Per Country The Philippines has a strong preference for U.S. -

Preventing Fraud and Deficit Through the Optimization of Health Insurance in Indonesia

Sys Rev Pharm 2020;11(7):228-231 A multifaceted review journal in the field of pharmacy Preventing Fraud and Deficit Through The Optimization of Health Insurance In Indonesia Sri Sunarti1, MT Ghozali2, Fahni Haris3,4, Ferry Fadzlul Rahman1,4*, Rofi Aulia Rahman5, Ghozali1 1 Department of Public Health, Universitas Muhammadiyah Kalimantan Timur; Indonesia 2 School of Pharmacy, Universitas Muhammadiyah Yogyakarta; Indonesia 3School of Nursing, Universitas Muhammadiyah Yogyakarta; Indonesia 4Department Healthcare Administration Asia University; Taiwan 5Department of Financial and Economic Law, Asia University; Taiwan *Corresponding Author: Ferry Fadzlul Rahman, Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT BPJS Kesehatan (Indonesian Health Insurance System) has been experiencing Keywords: BPJS Kesehatan, Fraud and Deficit, Healthcare System, a severe problem for many years that BPJS Kesehatan has been suffering a Supervisory System huge deficit. That situation is getting worse and taking a negative impact on hospitals, medical practitioners, and patients itself. The more severe problem Correspondence: felt by a patient who needs special treatment and medication. Due to the Ferry Fadzlul Rahman deficit of the BPJS Kesehatan budget, some hospitals owe some money to the 1 Department of Public Health, Universitas Muhammadiyah Kalimantan pharmaceutical company to buy some medicines. However, they cannot buy Timur; Indonesia the medication because they have no budget. This study is to explain and Email: [email protected] compare with the National Health Insurance System in Taiwan to resolve the problems within BPJS Kesehatan in Indonesia, notably on the supervisory system between 2 (two) countries. The method used in this study is the Systematic Literature Review (SLR) method with qualitative approval from secondary data in approving, reviewing, evaluating, and research supporting all available research in 2015-2020. -

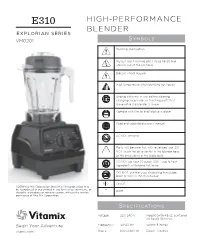

HIGH-PERFORMANCE BLENDER EXPLORIAN SERIES VM0201 S Y M B O L S

E310 HIGH-PERFORMANCE BLENDER EXPLORIAN SERIES VM0201 S YMBOL S Warning and Caution NEVER touch moving parts. Keep hands and utensils out of the container. Electric Shock Hazard High temperature when blending hot liquids Unplug while not in use, before cleaning, changing accessories or touching parts that move while the blender is in use Operate with the lid and lid plug in place Read and understand owner’s manual DO NOT immerse Parts will become hot with extended use. DO NOT touch the drive socket in the blender base or the drive spline in the blade base DO NOT use your 20 ounce (0.6 L) cup to heat ingredients or to blend hot liquids DO NOT use the cups (including the blade base or lids) in the microwave I O On/Off ©2018 Vita-Mix Corporation. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, or pulse stored in a database or retrieval system, without the written permission of Vita-Mix Corporation. S PECIFICATION S Voltage: 220-240 V Height (with 48 oz. container on base): 18 inches Begin Your Adventure Frequency: 50-60 Hz Width: 8 inches vitamix.com Watts: 1000-1200 W Depth: 11 inches I M P O R TA N T I N STRUCTION S FOR S AFE U S E WARNING: to avoid the risk of serious injury when using your Vitamix® blender, basic safety precau- tions should be followed, including the following. READ ALL INSTRUCTIONS, SAFEGUARDS AND WARNINGS BEFORE OPERATING BLENDER. 1. Read all instructions. -

CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION 1.1 Research Object Overview 1.1.1.1

CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION 1.1 Research Object Overview 1.1.1.1 An overview of PT Sumber Alfaria Trijaya Tbk Founded in 1989 by Djoko Susanto and family, PT Sumber Alfaria Trijaya Tbk (Alfamart/Company) started business in the field of trade and distribution. In 1999, it expanded the business to minimarket. Exponential expansion began in 2002 with the acquisition of 141 Alfa Minimart outlets and a new name ‘Alfamart’ (PT Sumber Alafaria Trijaya Tbk Annual Report, 2013). Currently, Alfamart is at the forefront of the retail business, serving more than 2.7 million customers each day in more than 8,500 stores across Indonesia. Supported by more than 90,000 employees, Alfamart is currently one of the largest job providers in Indonesia (PT Sumber Alafaria Trijaya Tbk Annual Report, 2013). Alfamart carries out its vision, mission and philosophy to be a community store. Therefore, in addition to trying to meet the needs and convenience of the customer by providing basic needs at affordable prices, convenient shopping place as well as an easily accessible location (PT Sumber Alafaria Trijaya Tbk Annual Report, 2013). The Company is also seeks to improving the community welfare through Corporate Social Responsibility programs based on 6 pillars: Alfamart Care, Alfamart Smart, Alfamart Sport, Alfamart Clean and Green, Alfamart SME’s and Alfamart Vaganza. In addition, Alfamart also empowers local people and institutions through franchising schemes that give rise to new entrepreneurs and new jobs (PT Sumber Alafaria Trijaya Tbk Annual Report, 2013). Alfamart committed to fostering a service culture at each organizational level and for every stakeholder. -

Holiday Turkey

Holiday Turkey You can buy different types of turkeys to cook. Read the label on the turkey carefully. Fresh Turkey Frozen Stuffed Frozen Turkey without Stuffing Look for a best-before date on the Turkey Take the turkey out of the freezer package. You must cook the turkey You can also buy a and thaw in the refrigerator. before this date. frozen turkey that Leave the turkey in its original wrapping. What if there is no date on the has stuffing inside. Put it in a large pan. Put it in the coldest package? You can keep the turkey You do not thaw part of the refrigerator. in the refrigerator for 1 - 2 days this turkey - cook it It will take about 10 hours per kilogram before you cook it. from frozen! Follow (about 5 hours per pound) to thaw. For It takes longer to cook a fresh the directions on example, it could take 2 days for a small turkey. Add 5 minutes per kilogram the label. turkey and 4 days for a large turkey. (3 minutes per pound) to the times You must cook a thawed turkey in the cooking chart. within 24 hours. 1 Prepare the turkey 2 Cook turkey at 425°F for Preheat the oven to 425°F. the first 30 minutes Take the plastic off the turkey. Then turn the oven down to 325°F. Continue roasting for: Take out the neck and bag of giblets. Don’t leave them inside the turkey. 4.5 kg (10 lb) 2 1/4 – 2 1/2 hours You can cook the neck alongside the turkey or you 7 kg (15 lb) 2 1/2 – 3 hours can use the neck, heart and gizzard to make stock 9 kg (20 lb) 3 1/2 – 4 hours or gravy. -

Venturist™ Series S Y M B O L S

Venturist™ Series S YMBOL S V1200I AND V1500I HIGH-PERFORMANCE BLENDERS Warning and Caution VM0195E NEVER touch moving parts. Keep hands and utensils out of Your Adventure Awaits the container Electric Shock Hazard High temperature when blending hot liquids Unplug while not in use, before cleaning, changing accessories or touching parts that move while the blender is in use Operate with the lid and lid plug in place Read and understand owner’s manual DO NOT immerse Parts will become hot with extended use. DO NOT touch the drive socket in the blender base or the drive spline in the blade base DO NOT use your 20 oz. (0.6 L) cup or 8 oz. (240 ml) bowl to heat ingredients or to blend hot liquids. Standby (Model V1500i) I/O On/Off I Start/Stop Pulse S PECIFICATION S Model V1500i Program Symbols (correspond to Vitamix Recipes) - Voltage: 220/240 V Height (with 64 oz. (2 L) container on blender Note: V1200i does not include programs base): 17 inches Smoothies Frequency: 50 - 60 Hz Width: 8 inches Watts 1200-1400 W Depth: 11 inches Frozen Desserts • This device complies with part 15 of the FCC Rules. Operation is subject to the following two conditions: (1) This device may not cause harmful interference, and (2) this device must accept any interference received, including interference that Soups may cause undesired operation. • This device complies with Industry Canada licence-exempt RSS standard(s). Operation is subject to the following two conditions: (1) this device may not Self-Cleaning cause interference, and (2) this device must accept any interference, including interference that may cause undesired operation of the device. -

10026 S Ubje Ct to a P P Ro V

DELHI CHARTER TOWNSHIP MINUTES OF REGULAR MEETING HELD ON AUGUST 8, 2018 Delhi Charter Township Board of Trustees met in a regular meeting on Wednesday, August 8, 2018 in the Multipurpose Room at the Community Services Center, 2074 Aurelius Road, Holt, Michigan. Supervisor Hayhoe called the meeting to order at 7:00 p.m. PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE ROLL CALL Members Present: Supervisor John Hayhoe, Clerk Evan Hope, Treasurer Roy Sweet, Trustees Stuart Goodrich, Tom Lenard, DiAnne Warfield Members Absent: Trustee Pat Brown COMMENTS FROM THE PUBLIC – None SET/ADJUST AGENDA Hope moved, Goodrich supported, to add Late Agenda Item F under Consent Agenda – Holt Community Arts Council’s Request to Serve Alcohol in Veterans Memorial Gardens. A Voice Poll Vote was recorded as follows: All Ayes Absent: Brown MOTION CARRIED CONSENT AGENDA SUBJECT TO APPROVAL A. Approval of Minutes – Committee Meeting of July 17, 2018 B. Approval of Minutes – Regular Meeting of July 18, 2018 C. Approval of Claims – July 18, 2018 (ATTACHMENT I) D. Approval of Claims – July 31, 2018 (ATTACHMENT II) E. Approval of Payroll – July 26, 2018 (ATTACHMENT III) F. Holt Community Arts Council’s Request to Serve Alcohol in Veterans Memorial Gardens (ATTACHMENT IV) Warfield moved, Goodrich supported, to approve the Consent Agenda as presented. A Voice Poll was recorded as follows: Ayes: Warfield, Goodrich, Hayhoe, Hope, Lenard, Sweet Absent: Brown MOTION CARRIED 10026 DELHI CHARTER TOWNSHIP MINUTES OF REGULAR MEETING HELD ON AUGUST 8, 2018 NEW BUSINESS SPECIAL USE PERMIT NO. 18-286 – 1795 CEDAR STREET - FAIRYTALES DAYCARE – TAX PARCEL #33-25-05-23-251-022 – CHILD CARE CENTER The Board reviewed a memorandum dated July 31, 2018 from Tracy Miller, Director of Community Development (ATTACHMENT V). -

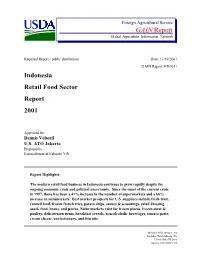

GAIN Report Global Agriculture Information Network

Foreign Agricultural Service GAIN Report Global Agriculture Information Network Required Report - public distribution Date: 11/19/2001 GAIN Report #ID1031 Indonesia Retail Food Sector Report 2001 Approved by: Dennis Voboril U.S. ATO Jakarta Prepared by: Kussusilowati & Fahwani Y.R. Report Highlights: The modern retail food business in Indonesia continues to grow rapidly despite the ongoing economic crisis and political uncertainty. Since the onset of the current crisis in 1997, there has been a 41% increase in the number of supermarkets and a 66% increase in minimarkets. Best market prospects for U.S. suppliers include fresh fruit, canned food, frozen french fries, potato chips, sauces & seasonings, salad dressing, snack food, beans, and pastas. Niche markets exist for frozen pizzas, frozen meat & poultry, delicatessen items, breakfast cereals, non-alcoholic beverages, tomato paste, cream cheese, confectionary, and biscuits. Includes PSD changes: No Includes Trade Matrix: No Unscheduled Report Jakarta ATO [ID2], ID GAIN Report #ID1031 Page 1 of 13 RETAIL FOOD SECTOR REPORT: INDONESIA SECTION I. MARKET SUMMARY Retail System The traditional sector still dominates the retail food business in Indonesia, but the data shown below indicates a growing trend towards the supermarket and other modern retail outlets. In 2001, an A.C. Nielsen study indicates that there were 1,903,602 retail food outlets in Indonesia. Of these outlets, 814 were supermarkets (up 41 percent since Retail Outlet Share of Market 1997), 3,051 were mini-markets (up 99 percent) 59,055 were large provision shops (no change), Warung 599,489 were small provision shops (up 66 (65.2%) Traditional Small percent), and 1,241,193 were warung provision Traditional Large shops (up 18 percent).1 Other (Supermkt & Minimkt) (0.2%) (3.1%) It is currently estimated by trade sources that 25 percent of retail food sales in Jakarta take place in supermarkets and other modern retail outlets. -

Horticultural Producers and Supermarket Development in Indonesia

38543 Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Report No. 38543-ID HORTICULTURAL PRODUCERS AND SUPERMARKET DEVELOPMENT IN INDONESIA REPUBLIC OF INDONESIA THE WORLD BANK OFFICE JAKARTA Jakarta Stock Exchange Building Tower II/12th Fl. Jl. Jend. Sudirman Kav. 52-53 Jakarta 12910 Tel: (6221) 5299-3000 Fax: (6221) 5299-3111 Website: http://www.worldbank.org/id THE WORLD BANK 1818 H Street N.W. Washington, D.C. 20433, U.S.A. Tel: (202) 458-1876 Fax: (202) 522-1557/1560 Email: [email protected] Website: http://www.worldbank.org East Asia and Pacific Region Rural Development, Natural Resources and Environment Sector Unit Sustainable Development Department Website: http://www.worldbank.org/eaprural Printed in June 2007 This volume is a product of staff of the World Bank. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed herein do not necessarily reflect the views of the Board of Executive Directors of the World Bank or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of the World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement of acceptance of such boundaries. HORTICULTURAL PRODUCERS AND SUPERMARKET DEVELOPMENT IN INDONESIA ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS AARD Agency for Agricultural Research and Development ACIAR Australian Centre for International Agricultural -

Farabi Kazakh National University MECHANICS and MATHEMATICS FACULTY MAGISTRASY

The Ministry of Education and Science of the Republic of Kazakhstan Al - Farabi kazakh national university MECHANICS AND MATHEMATICS FACULTY MAGISTRASY Department of mathematical and computer modeling MASTER'S DISSERTATION Methods of producing the synthetic detergents by mathematical modeling Creator ____________ Arpan G. «___» _________________2018 / signature / Norm controller ____________ Karibaeva M.«___» _______________ 2018 / signature / Supervisor ___________________ Issakhov A. «___»_______________2018 PhD, professor / signature / Approved for protection: Head of department ____________ Issakhov A. «___»_______________2018 PhD / signature / ALMATY 2018 ТҮЙІНДЕМЕ Диссертациялық жұмыс 64 бет, 38 сурет, 18 әдебиеттер тізімінен тұрады. Кілттік сөздер: синтетикалық жуғыш заттар, натрий гексафосфат, ысыту, Навье-Стокс теңдеуі, уақыт. Жұмыстың мақсаты - синтетикалық жуғыш заттарды алу кезіндегі натрий гексафосфатты ысыту жүйелерін модельдеу. Тақырып өзектілігі - Тұрмыста пайдаланылатын химиялық заттар – қазіргі уақытта дамыған өндірістің өніміне айналып отыр. Үйдегі тазалық жұмыстарында оларды пайдаланбау мүмкін емес. Ең алғашқы синтетикалық жуғыш құрал 1916 жылы пайда болған. Неміс химигі Фринц Понтердің тапқан өнертабысы тек өнеркәсіптік қолдануға арналған болатын. Тұрмыстық СЖЗ 1935 жылдан бастап шығарыла бастады, сол кезден бастап олардың қол терісіне зияндылығы азайды. Өндірістік орындар үшін аз уақыт ішінде, аз энергияны пайдалану арқылы синтетикалық жуғыш заттарды алу өте тиымды. Зерттеу жұмысының нысаны- синтетикалық жуғыш заттар