Creating the Cult of 'Cousin Jack': Cornish Miners in Latin America

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Perspectives on Solar Energy, Mining and Agro-Food in Chile

Chapter 3 Transforming industries: Perspectives on solar energy, mining and agro-food in Chile The shifting global geopolitical and technological landscape coupled with changes in consumers’ preferences is opening up a window of opportunity for Chile. The country could transform its economy, enlarge its knowledge base and increase productivity by leveraging on its natural assets in new, more innovative ways. However, the world is moving fast and opportunities will not be permanently available. To tap into them, a strategic approach and a shared vision between government, business and society is needed. Chile has started to do so through strategic initiatives that identify future opportunities and clarify gaps to be addressed. This chapter presents the Chilean experience in solar energy, mining and agro-food; in each case it presents a snapshot of key trends and future scenarios, developed through multi-stakeholder consultations, it describes the current policy approach and it identifies reforms to move forward. PRODUCTION TRANSFORMATION POLICY REVIEW OF CHILE: REAPING THE BENEFITS OF NEW FRONTIERS © OECD AND UNITED NATIONS 2018 103 3. Transforming industries: Perspectives on solar energy, mining and agrO-food in Chile Unleashing the potential of solar energy in Chile This section presents a snapshot of the rise of solar energy in the country and summarises the results of public-private consultations on the opportunities presented by solar for Chile. It describes the current policy approach and it identifies reforms to move forward. Solar energy is gaining ground in Chile Solar energy is becoming globally competitive thanks to falling prices. Investment in the development of renewable energies globally is surpassing investment in fossil fuel technologies (OECD, 2018; IEA, 2016). -

View in Website Mode

25 bus time schedule & line map 25 Fowey - St Austell - Newquay View In Website Mode The 25 bus line (Fowey - St Austell - Newquay) has 5 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Fowey: 6:40 AM - 4:58 PM (2) Newquay: 5:55 AM - 3:55 PM (3) St Austell: 5:58 PM (4) St Austell: 5:55 PM (5) St Stephen: 4:55 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 25 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 25 bus arriving. Direction: Fowey 25 bus Time Schedule 94 stops Fowey Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 6:40 AM - 4:58 PM Bus Station, Newquay 16 Bank Street, Newquay Tuesday 6:40 AM - 4:58 PM East St. Post O∆ce, Newquay Wednesday 6:40 AM - 4:58 PM 40 East Street, Newquay Thursday 6:40 AM - 4:58 PM Great Western Hotel, Newquay Friday 6:40 AM - 4:58 PM 36&36A Cliff Road, Newquay Saturday 6:40 AM - 4:58 PM Tolcarne Beach, Newquay 12A - 14 Narrowcliff, Newquay Barrowƒeld Hotel, Newquay 25 bus Info Hilgrove Road, Trenance Direction: Fowey Stops: 94 Newquay Zoo, Trenance Trip Duration: 112 min Line Summary: Bus Station, Newquay, East St. Post The Bishops School, Treninnick O∆ce, Newquay, Great Western Hotel, Newquay, Tolcarne Beach, Newquay, Barrowƒeld Hotel, Kew Close, Treloggan Newquay, Hilgrove Road, Trenance, Newquay Zoo, Kew Close, Newquay Trenance, The Bishops School, Treninnick, Kew Close, Treloggan, Dale Road, Treloggan, Polwhele Road, Dale Road, Treloggan Treloggan, Near Morrisons Store, Treloggan, Carn Brae House, Lane, Hendra Terrace, Hendra Holiday Polwhele Road, Treloggan Park, Holiday -

An Historic Relationship by JACQUES ARNOLD Special Advisor for Latin America, FIRST

COLOMBIA An historic relationship BY JACQUES ARNOLD SPECIAL ADVISOR FOR LATIN AMERICA, FIRST his historic first-ever State Visit to the Centre for Peace, Memory and Reconciliation in United Kingdom by a President of the Bogotá, accompanied by the President and his First Republic of Colombia, carried out this Lady, when the Prince spoke to families of victims, of week by President Juan Manuel Santos, is his own experiences during the conflict in Northern yetT another milestone in the centuries-old relationship Ireland, and the “bewildering and soul-destroying between our two countries. A resident of London for anguish” he felt on learning of the death of his uncle nine years from 1972, he was a representative for the Lord Mountbatten, who died in an IRA bomb attack. National Confederation of Coffee Growers at the He continued, “It is an immense tragedy that violence International Coffee Organisation, itself based in has cast such a long shadow across the whole of this London, and previously he had studied for a Master’s remarkable country for the past five decades. Many JACQUES ARNOLD degree in Economics and Development at the London of you here today will have experienced unimaginable was Midland Bank’s School of Economics. He has many personal friends suffering, and our hearts go out to you as you struggle Deputy Representative in in London. to come to terms with all that has happened to you and Brazil, establishing their The State Visit follows the successful visit to your loved ones.” Following the successful conclusion Representative Office in Colombia in 2014 by the Prince of Wales and the of the Peace Accords, and a permanent ceasefire São Paulo in 1976. -

Historical Background of the Contact Between Celtic Languages and English

Historical background of the contact between Celtic languages and English Dominković, Mario Master's thesis / Diplomski rad 2016 Degree Grantor / Ustanova koja je dodijelila akademski / stručni stupanj: Josip Juraj Strossmayer University of Osijek, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences / Sveučilište Josipa Jurja Strossmayera u Osijeku, Filozofski fakultet Permanent link / Trajna poveznica: https://urn.nsk.hr/urn:nbn:hr:142:149845 Rights / Prava: In copyright Download date / Datum preuzimanja: 2021-09-27 Repository / Repozitorij: FFOS-repository - Repository of the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Osijek Sveučilište J. J. Strossmayera u Osijeku Filozofski fakultet Osijek Diplomski studij engleskog jezika i književnosti – nastavnički smjer i mađarskog jezika i književnosti – nastavnički smjer Mario Dominković Povijesna pozadina kontakta između keltskih jezika i engleskog Diplomski rad Mentor: izv. prof. dr. sc. Tanja Gradečak – Erdeljić Osijek, 2016. Sveučilište J. J. Strossmayera u Osijeku Filozofski fakultet Odsjek za engleski jezik i književnost Diplomski studij engleskog jezika i književnosti – nastavnički smjer i mađarskog jezika i književnosti – nastavnički smjer Mario Dominković Povijesna pozadina kontakta između keltskih jezika i engleskog Diplomski rad Znanstveno područje: humanističke znanosti Znanstveno polje: filologija Znanstvena grana: anglistika Mentor: izv. prof. dr. sc. Tanja Gradečak – Erdeljić Osijek, 2016. J.J. Strossmayer University in Osijek Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Teaching English as -

Cornwall. Pub 1445

TRADES DIRECTORY.] CORNWALL. PUB 1445 . Barley Sheaf, Mrs. Mary Hawken, Lower Bore st. Bodmin Commercial hotel,John Wills,Dowugate,Linkiuhorne,Liskrd Barley Sheaf, Mrs. Elizabeth Hill, Church street, Liskeard Commercial hotel & posting house, Abraham Bond, Gunnis~ Barley Sheaf inn, Fred Liddicoat, Union square, St. Columb lake, Tavistock Major R.S.O Commercial hotel & posting establishment (Herbert Henry Barley Sheaf hotel, Mrs. Elizh. E. Reed, Old Bridge st. Truro Hoare, proprietor), Grampound Road Barley Sheaf, William Richards, Gorran, St. Austell Commercial hotel, family, commercial & posting house, Basset Arms, William Laity, Basset road, Camborne William Alfred Holloway, Porthleven, Helston Basset Arms, Solomon Rogers, Pool, Carn Brea R.S. 0 Commercial hotel, family, commercial & posting, Richard Basset Arms, Charles Wills, Portreath, Redruth Lobb. South quay, Padstow R.S.O Bay Tree, Mrs. Elizabeth Rowland, Stratton R.S.O Cornish Arms, Thomas Butler, Crockwell street, Bodmin .Bennett's Arms, Charles Barriball, Lawhitton, Launceston Cornish Arms, Jarues Collins, Wadebridge R.S.O Bell inn, William Ca·rne, Meneage street, Helston Cornish Arms, Mrs. Elizh. Eddy, Market Jew st. Penzance Bell inn, Daniel Marshall, Tower street, Launceston Cornish Arms, Jakeh Glasson, Trelyon, St. Ives R.S.O Bell commercial hotel & posting house, Mrs. Elizabeth Cornish Arms, Nicholas Hawken, Pendoggett, St. Kew, Sargent, Church street, Li.skeard Wadebridge R.S.O Bideford inn, Lewis Butler, l:ltratton R.S. 0 Cornish Arms, William LObb, St. Tudy R.S.O Black Horse, Richard Andrew, Kenwyn street, Truro CornishArms,Mrs.M.A. Lucas,St. Dominick,St. MellionR. S. 0 BliBland inn, Mrs. R. Williams, Church town,Blislaud,Bodmin Cornish Arms, Rd. -

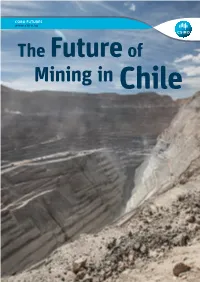

The Future of Mining in Chile

CSIRO FUTURES www.csiro.au The Future of Mining in Chile i Cover image: CODELCO’s Chuquicamata open pit copper mine near Calama, Chile AUTHORS Meredith Simpson (CSIRO Futures) Enrique Aravena (CSIRO Chile) James Deverell (CSIRO Futures) COPYriGHT AND DiscLAIMER © 2014 CSIRO. To the extent permitted by law, all rights are reserved and no part of this publication covered by copyright may be reproduced or copied in any form or by any means except with the written permission of CSIRO. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS In the course of developing this report, CSIRO engaged with and received valuable input from a number of stakeholders. We are especially grateful for the time and input provided by the following stakeholders: AngloAmerican Chile Antofagasta Minerals Antofagasta Regional Government BHP Billiton Chile CICITEM (El Centro de Investigación Científico Tecnológico Para la Minería) COCHILCO (Comisión Chilena del Cobre) Consejo Minero CORFO (Corporación de Fomento de la Producción de Chile) Fundación Chile INAPI (Instituto Nacional de Propiedad Industrial) Komatsu Chile Ministerio de Economía, Fomento y Turismo de Chile Ministerio de Energía de Chile Ministerio de Minería de Chile SERNAGEOMIN (Servicio Nacional de Geología y Minería) Universidad Católica del Norte Universidad de Antofagasta Universidad de Chile ii The Future of Mining in Chile Prólogo Prologue Este trabajo es el fruto del esfuerzo conjunto entre This work is the result of a joint effort between the el Centro de Excelencia en Minería y Procesamiento CSIRO Chile Centre for Excellence in Mining and Mineral Mineral de CSIRO Chile y CSIRO Futures, el brazo de Processing and CSIRO Futures, the strategic foresighting análisis estratégico prospectivo de CSIRO. -

Health and Adult Social Care Overview and Scrutiny Committee

Health and Adult Social Care Overview and Scrutiny Committee Rob Rotchell (Chairman) 2 Green Meadows Camelford Cornwall PL32 9UD 07828 980157 [email protected] Mike Eathorne-Gibbons (Vice-Chairman) 27 Lemon Street Truro Cornwall TR1 2LS 01872 275007 07979 864555 [email protected] Candy Atherton Top Deck Berkeley Path Falmouth Cornwall TR11 2XA 07587 890588 [email protected] John Bastin Eglos Cot Churchtown Budock Falmouth 01326 368455 [email protected] Nicky Chopak The Post House Tresmeer Launceston PL15 8QU 07810 302061 [email protected] Dominic Fairman South Penquite Farm Blisland Bodmin PL30 4LH 07939 122303 [email protected] Mario Fonk 25 Penarwyn Crescent, Heamoor, Penzance, TR18 3JU 01736 332720 [email protected] Loveday Jenkin Tremayne Farm Cottage Tremayne Praze an Beeble Camborne TR14 9PH 01209 831517 [email protected] Phil Martin Roseladden Mill Farm Sithney Helston Cornwall TR13 0RL 01326 569923 07533 827268 [email protected] Andrew Mitchell 36 Parc-An-Creet St Ives Cornwall TR26 2ES 01736 797538 07592 608390 [email protected] Karen McHugh C/O County Hall Treyew Road Truro Cornwall TR1 3AY 07977564422 [email protected] Sue Nicholas Brigstock, 8 Bampfylde Way Perran Downs, Goldsithney Penzance Cornwall TR20 9JJ 01736 711090 [email protected] David Parsons 56 Valley Road Bude Cornwall EX23 8ES 01288 354939 [email protected] John Thomas Gwel-An-Eglos, Church Row Lanner Redruth Cornwall TR16 6ET 01209 215162 07503 547852 [email protected] -

Cornwall Council Altarnun Parish Council

CORNWALL COUNCIL THURSDAY, 4 MAY 2017 The following is a statement as to the persons nominated for election as Councillor for the ALTARNUN PARISH COUNCIL STATEMENT AS TO PERSONS NOMINATED The following persons have been nominated: Decision of the Surname Other Names Home Address Description (if any) Returning Officer Baker-Pannell Lisa Olwen Sun Briar Treween Altarnun Launceston PL15 7RD Bloomfield Chris Ipc Altarnun Launceston Cornwall PL15 7SA Branch Debra Ann 3 Penpont View Fivelanes Launceston Cornwall PL15 7RY Dowler Craig Nicholas Rivendale Altarnun Launceston PL15 7SA Hoskin Tom The Bungalow Trewint Marsh Launceston Cornwall PL15 7TF Jasper Ronald Neil Kernyk Park Car Mechanic Tredaule Altarnun Launceston Cornwall PL15 7RW KATE KENNALLY Dated: Wednesday, 05 April, 2017 RETURNING OFFICER Printed and Published by the RETURNING OFFICER, CORNWALL COUNCIL, COUNCIL OFFICES, 39 PENWINNICK ROAD, ST AUSTELL, PL25 5DR CORNWALL COUNCIL THURSDAY, 4 MAY 2017 The following is a statement as to the persons nominated for election as Councillor for the ALTARNUN PARISH COUNCIL STATEMENT AS TO PERSONS NOMINATED The following persons have been nominated: Decision of the Surname Other Names Home Address Description (if any) Returning Officer Kendall Jason John Harrowbridge Hill Farm Commonmoor Liskeard PL14 6SD May Rosalyn 39 Penpont View Labour Party Five Lanes Altarnun Launceston Cornwall PL15 7RY McCallum Marion St Nonna's View St Nonna's Close Altarnun PL15 7RT Richards Catherine Mary Penpont House Altarnun Launceston Cornwall PL15 7SJ Smith Wes Laskeys Caravan Farmer Trewint Launceston Cornwall PL15 7TG The persons opposite whose names no entry is made in the last column have been and stand validly nominated. -

Zoomcast with Jennifer Hayward, Jessie Reeder & Michelle Prain Brice

Zoomcast with Michelle Prain Brice, Jennifer Hayward, and Jessie Reeder Speakers: Michelle Prain Brice (guest), Jennifer Hayward (guest), Jessie Reeder (guest) Ryan Fong (host) Date: February 25, 2021 Length: 35:39 Zoomcast Series: Beyond the Literary Rights: Undisciplining the Victorian Classroom, CC BY 4.0 Citation: “Zoomcast with Michelle Prain Brice, Jennifer Hayward, and Jessie Reeder.” Hosted by Ryan Fong. Undisciplining the Victorian Classroom, 2021, https://undiscipliningvc.org/html/zoomcasts/ brice-hayward-reeder.html. - So hello and welcome everyone. I'm Ryan Fong, and I'm one of the co-founders and organizers of Undisciplining the Victorian Classroom. And as one of the forms of content that we're generating for this site, these Zoomcasts are meant to be a mechanism that will allow us to stage different conversations where we can think together about our classroom practices and about our processes of learning and unlearning as teachers. How can we grow together as a community of scholars and learn from one another? Especially in moving beyond the boundaries of our field and training is one of the key questions that we'll be asking in these Zoom casts and that I hope to explore today with these fine folks. So this is the second in a cluster of Zoomcasts that I'm leading on moving beyond the strict and traditional confines of what we consider to be the literary and how and why this is so important to the work of undisciplining Victorian studies and building anti-racist and anti-colonial practices in our classroom spaces. Today, I'm joined by the three organizers of the Anglophone Chile Project, Jennifer Hayward, who is professor of English at Worcester College, Michelle Prain Brice, a professor at Universidad Adolfo Ibañez and Pontificia Universidad Catolica de Valparaíso and Jessie Reader, assistant professor of English at Binghamton university. -

Productivity in the Chilean Copper Mining Industry

PRODUCTIVITY IN THE CHILEAN COPPER MINING INDUSTRY EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 Executive Summary Importance of Mining in Chile Mining, specifically copper mining is the most significant economic activity in Chile. Copper mining represents over 10% of GDP, more than 50% of exports, and is the leading recipient of foreign direct investment: accounting for one in every three dollars entering the country. The sector has grown steadily in the past 60 years: it tripled between 1960 and 1990; and trebled again during 1990-2016, reaching 5.5 million tons in 2016 causing Chile to be the world's leading producer, accounting for 30% of total production. The country also boasts a third of the known world reserves, the largest at a global level. Copper opens a window of opportunity to expand our development, and thus achieve economic and social progress. Given the sharp price increase during 2004-2014, Chile raised not only its copper production but also its value. Exports grew from an average of US$1.4 billion1 between 1960 and 1990 to US$5.5 billion between 1990 and 2003 and then US$34 billion during the so-called "super-cycle" (2004-2014). The value exported in 2016 was of US$28 billion. Between 1994 and 2003, mining accounted for approximately 6% of fiscal revenues, a contribution that tripled between 2004 and 2014, reaching an annual average of 20%. Including state enterprises (Codelco and Enami), copper contributed US$96 billion to the treasury in 2004-2014, ten times more than the previous decade (US$9 billion). This allowed the accumulation of more than US$20 billion in Sovereign Wealth Funds2. -

Gardens Guide

Gardens of Cornwall map inside 2015 & 2016 Cornwall gardens guide www.visitcornwall.com Gardens Of Cornwall Antony Woodland Garden Eden Project Guide dogs only. Approximately 100 acres of woodland Described as the Eighth Wonder of the World, the garden adjoining the Lynher Estuary. National Eden Project is a spectacular global garden with collection of camellia japonica, numerous wild over a million plants from around the World in flowers and birds in a glorious setting. two climatic Biomes, featuring the largest rainforest Woodland Garden Office, Antony Estate, Torpoint PL11 3AB in captivity and stunning outdoor gardens. Enquiries 01752 814355 Bodelva, St Austell PL24 2SG Email [email protected] Enquiries 01726 811911 Web www.antonywoodlandgarden.com Email [email protected] Open 1 Mar–31 Oct, Tue-Thurs, Sat & Sun, 11am-5.30pm Web www.edenproject.com Admissions Adults: £5, Children under 5: free, Children under Open All year, closed Christmas Day and Mon/Tues 5 Jan-3 Feb 16: free, Pre-Arranged Groups: £5pp, Season Ticket: £25 2015 (inclusive). Please see website for details. Admission Adults: £23.50, Seniors: £18.50, Children under 5: free, Children 6-16: £13.50, Family Ticket: £68, Pre-Arranged Groups: £14.50 (adult). Up to 15% off when you book online at 1 H5 7 E5 www.edenproject.com Boconnoc Enys Gardens Restaurant - pre-book only coach parking by arrangement only Picturesque landscape with 20 acres of Within the 30 acre gardens lie the open meadow, woodland garden with pinetum and collection Parc Lye, where the Spring show of bluebells is of magnolias surrounded by magnificent trees. -

Tremayne Family History

TREMAYNE FAMILY HISTORY 1 First Generation 1 Peter/Perys de Tremayne (Knight Templar?) b abt 1240 Cornwall marr unknown abt 1273.They had the following children. i. John Tremayne b abt 1275 Cornwall ii. Peter Tremayne b abt 1276 Cornwall Peter/Perys de Tremayne was Lord of the Manor of Tremayne in St Martin in Meneage, Cornwall • Meneage in Cornish……Land of the Monks. Peter named in De Banco Roll lEDWl no 3 (1273) SOME FEUDAL COATS of ARMS by Joseph Foster Perys/Peter Tremayne. El (1272-1307). Bore, gules, three dexter arms conjoined and flexed in triangle or, hands clenched proper. THE CARTULARY OF ST. MICHAELS MOUNT. The Cartulary of St Michaels Mount contains a charter whereby Robert, Count of Mortain who became Earl of Cornwall about 1075 conferred on the monks at St Michaels Mount 3 acres in Manech (Meneage) namely Treboe, Lesneage, Tregevas and Carvallack. This charter is confirmed in substance by a note in the custumal of Otterton Priory that the church had by gift of Count Robert 2 plough lands in TREMAINE 3 in Traboe 3 in Lesneage 2 in Tregevas and 2 in Carvallack besides pasture for all their beasts ( i.e. on Goonhilly) CORNISH MANORS. It was usual also upon Cornish Manors to pay a heriot (a fine) of the best beast upon the death of a tenant; and there was a custom that if a stranger passing through the County chanced to die, a heriot of his best beast was paid, or his best jewel, or failing that his best garments to the Lord of the Manor.