Wired 11.05: MATRIX2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Matrix As an Introduction to Mathematics

St. John Fisher College Fisher Digital Publications Mathematical and Computing Sciences Faculty/Staff Publications Mathematical and Computing Sciences 2012 What's in a Name? The Matrix as an Introduction to Mathematics Kris H. Green St. John Fisher College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://fisherpub.sjfc.edu/math_facpub Part of the Mathematics Commons How has open access to Fisher Digital Publications benefited ou?y Publication Information Green, Kris H. (2012). "What's in a Name? The Matrix as an Introduction to Mathematics." Mathematics in Popular Culture: Essays on Appearances in Film, Fiction, Games, Television and Other Media , 44-54. Please note that the Publication Information provides general citation information and may not be appropriate for your discipline. To receive help in creating a citation based on your discipline, please visit http://libguides.sjfc.edu/citations. This document is posted at https://fisherpub.sjfc.edu/math_facpub/18 and is brought to you for free and open access by Fisher Digital Publications at St. John Fisher College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. What's in a Name? The Matrix as an Introduction to Mathematics Abstract In my classes on the nature of scientific thought, I have often used the movie The Matrix (1999) to illustrate how evidence shapes the reality we perceive (or think we perceive). As a mathematician and self-confessed science fiction fan, I usually field questionselated r to the movie whenever the subject of linear algebra arises, since this field is the study of matrices and their properties. So it is natural to ask, why does the movie title reference a mathematical object? Of course, there are many possible explanations for this, each of which probably contributed a little to the naming decision. -

3.2 Bullet Time and the Mediation of Post-Cinematic Temporality

3.2 Bullet Time and the Mediation of Post-Cinematic Temporality BY ANDREAS SUDMANN I’ve watched you, Neo. You do not use a computer like a tool. You use it like it was part of yourself. —Morpheus in The Matrix Digital computers, these universal machines, are everywhere; virtually ubiquitous, they surround us, and they do so all the time. They are even inside our bodies. They have become so familiar and so deeply connected to us that we no longer seem to be aware of their presence (apart from moments of interruption, dysfunction—or, in short, events). Without a doubt, computers have become crucial actants in determining our situation. But even when we pay conscious attention to them, we necessarily overlook the procedural (and temporal) operations most central to computation, as these take place at speeds we cannot cognitively capture. How, then, can we describe the affective and temporal experience of digital media, whose algorithmic processes elude conscious thought and yet form the (im)material conditions of much of our life today? In order to address this question, this chapter examines several examples of digital media works (films, games) that can serve as central mediators of the shift to a properly post-cinematic regime, focusing particularly on the aesthetic dimensions of the popular and transmedial “bullet time” effect. Looking primarily at the first Matrix film | 1 3.2 Bullet Time and the Mediation of Post-Cinematic Temporality (1999), as well as digital games like the Max Payne series (2001; 2003; 2012), I seek to explore how the use of bullet time serves to highlight the medial transformation of temporality and affect that takes place with the advent of the digital—how it establishes an alternative configuration of perception and agency, perhaps unprecedented in the cinematic age that was dominated by what Deleuze has called the “movement-image.”[1] 1. -

CEO & Co-Founder, Pinscreen, Inc. Distinguished Fellow, University Of

HaoLi CEO & Co-Founder, Pinscreen, Inc. Distinguished Fellow, University of California, Berkeley Pinscreen, Inc. Email [email protected] 11766 Wilshire Blvd, Suite 1150 Home page http://www.hao-li.com/ Los Angeles, CA 90025, USA Facebook http://www.facebook.com/li.hao/ PROFILE Date of birth 17/01/1981 Place of birth Saarbrücken, Germany Citizenship German Languages German, French, English, and Mandarin Chinese (all fluent and no accents) BIO I am CEO and Co-Founder of Pinscreen, an LA-based Startup that builds the world’s most advanced AI-driven virtual avatars, as well as a Distinguished Fellow of the Computer Vision Group at the University of California, Berkeley. Before that, I was an Associate Professor (with tenure) in Computer Science at the University of Southern California, as well as the director of the Vision & Graphics Lab at the USC Institute for Creative Technologies. I work at the intersection between Computer Graphics, Computer Vision, and AI, with focus on photorealistic human digitization using deep learning and data-driven techniques. I’m known for my work on dynamic geometry processing, virtual avatar creation, facial performance capture, AI-driven 3D shape digitization, and deep fakes. My research has led to the Animoji technology in Apple’s iPhone X, I worked on the digital reenactment of Paul Walker in the movie Furious 7, and my algorithms on deformable shape alignment have improved the radiation treatment for cancer patients all over the world. I have been keynote speaker at numerous major events, conferences, festivals, and universities, including the World Economic Forum (WEF) in Davos 2020 and Web Summit 2020. -

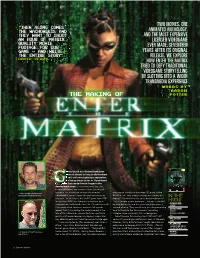

The Making of Enter the Matrix

TWO MOVIES. ONE “THEN ALONG COMES THE WACHOWSKIS AND ANIMATED ANTHOLOGY. THEY WANT TO SHOOT AND THE MOST EXPENSIVE AN HOUR OF MATRIX LICENSED VIDEOGAME QUALITY MOVIE FOOTAGE FOR OUR EVER MADE. SEVENTEEN GAME – AND WRITE YEARS AFTER ITS ORIGINAL THE ENTIRE STORY” RELEASE, WE EXPLORE DAVID PERRY HOW ENTER THE MATRIX TRIED TO DEFY TRADITIONAL VIDEOGAME STORYTELLING BY SLOTTING INTO A WIDER TRANSMEDIA EXPERIENCE Words by Aaron THE MAKING OF Potter ames based on a licence have been around almost as long as the medium itself, with most gaining a reputation for being cheap tie-ins or ill-produced cash grabs that needed much longer in the development oven. It’s an unfortunate fact that, in most instances, the creative teams tasked with » Shiny Entertainment founder and making a fun, interactive version of a beloved working on a really cutting-edge 3D game called former game director David Perry. Hollywood IP weren’t given the time necessary to Sacrifice, so I very embarrassingly passed on the IN THE succeed – to the extent that the ET game from 1982 project.” David chalks this up as being high on his for the Atari 2600 was famously rushed out by a “list of terrible career decisions”, though it wouldn’t KNOW single person and helped cause the US industry crash. be long before he and his team would be given a PUBLISHER: ATARI After every crash, however, comes a full system second chance. They could even use this pioneering DEVELOPER : reboot. And it was during the world’s reboot at the tech to translate the Wachowskis’ sprawling SHINY turn of the millennium, around the time a particular universe more accurately into a videogame. -

Instructables.Com/Id/How-To-Enter-The-Ghetto-Matrix-DIY-Bullet-Time/ License: Public Domain Dedication (Pd)

Home Sign Up! Explore Community Submit All Art Craft Food Games Green Home Kids Life Music Offbeat Outdoors Pets Photo Ride Science Tech How to Enter the Ghetto Matrix (DIY Bullet Time) by fi5e on December 19, 2007 Table of Contents License: Public Domain Dedication (pd) . 2 Intro: How to Enter the Ghetto Matrix (DIY Bullet Time) . 2 step 1: Tools & Materials . 4 step 2: Dimension . 8 step 3: Cut Wood . 9 step 4: Drill Holes . 10 step 5: Stand Connections . 11 step 6: Shutter Cable Hack . 13 step 7: the Control Box . 15 step 8: Setting Up the Rig . 20 step 9: Connecting All the Cameras . 22 step 10: Pick Your Spot! . 23 step 11: Ghetto Matrix Operations Quick-Start Guide . 24 step 12: Act a Fool Son! . 30 step 13: Post Production . 40 step 14: Fin . 42 Related Instructables . 43 Advertisements . 43 Comments . 43 http://www.instructables.com/id/How-to-Enter-the-Ghetto-Matrix-DIY-Bullet-Time/ License: Public Domain Dedication (pd) Intro: How to Enter the Ghetto Matrix (DIY Bullet Time) The following is a tutorial on how to build your own cheap, portable and hood-style bullet time camera rig on the cheap and the fly. This rig was designed by the Graffiti Research Lab and director Dan the Man to use in a hip-hop music video for underground rappers Styles P , AZ and the legendary Large Professor (spinning below). Just another chapter in the GRL's continuing mission to make open source the sixth element of hip-hop. Peep the vid at the resolution of the proletariat (below): Or see how the higher-res live here . -

Japanese Cinema at the Digital Turn Laura Lee, Florida State University

1 Between Frames: Japanese Cinema at the Digital Turn Laura Lee, Florida State University Abstract: This article explores how the appearance of composite media arrangements and the prominence of the cinematic mechanism in Japanese film are connected to a nostalgic preoccupation with the materiality of the filmic image, and to a new critical function for film-based cinema in the digital age. Many popular Japanese films from the early 2000s layer perceptually distinct media forms within the image. Manipulation of the interval between film frames—for example with stop-motion, slow-motion and time-lapse techniques—often overlays the insisted-upon interval between separate media forms at these sites of media layering. Exploiting cinema’s temporal interval in this way not only foregrounds the filmic mechanism, but it in effect stages the cinematic apparatus, displaying it at a medial remove as a spectacular site of difference. In other words, cinema itself becomes refracted through these hybrid media combinations, which paradoxically facilitate a renewed encounter with cinema by reawakening a sensuous attachment to it at the very instant that it appears to be under threat. This particular response to developments in digital technologies suggests how we might more generally conceive of cinema finding itself anew in the contemporary media landscape. The advent of digital media and the perceived danger it has implied for the status of cinema have resulted in an inevitable nostalgia for the unique properties of the latter. In many Japanese films at the digital turn this manifests itself as a staging of the cinematic apparatus, in 1 which cinema is refracted through composite media arrangements. -

Matrix : from Representation to Simulation and Beyond

Lakehead University Knowledge Commons,http://knowledgecommons.lakeheadu.ca Electronic Theses and Dissertations Retrospective theses 2006 Matrix : from representation to simulation and beyond Bryx, Adam http://knowledgecommons.lakeheadu.ca/handle/2453/3345 Downloaded from Lakehead University, KnowledgeCommons The Matrix: From Representation to Simulation and Beyond A thesis submitted to the Department of English Lakehead University, Thunder Bay, Ontario in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in English By Adam Bryx May 2006 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Library and Bibliothèque et 1 ^1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l'édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-21530-2 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-21530-2 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce,Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve,sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l'Internet, prêter, telecommunication or on the Internet,distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, électronique commercial purposes, in microform,et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriété du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protège cette thèse. -

BEFORE the PHILOSOPHY There Are Several Ways That We Might Explain the Location of the Matrix

ONE BEFORE THE 7 PHILOSOPHY UNDERSTANDING THE FILMS BEFORE THE PHILOSOPHY I’m really struggling here. I’m trying to keep up, but I’m losing the plot. There is way too much weird shit going on around here and nothing is going the way it is supposed to go. I mean, doors that go nowhere and everywhere, programs acting like humans, multiplying agents . Oh when, when will it end? – SparksE The Matrix films often left audiences more confused than they had bargained for. Some say that their confusion began with the very first film, and was compounded with each sequel. Others understood the big picture, but found themselves a bit perplexed concerning the details. It’s safe to say that no one understands the films completely – there are always deeper levels to consider. So before we explore the more philosophical aspects of the films, I hope to clarify some of the common points of confusion. But first, I strongly encourage you to watch all three films. There are spoilers ahead. The Matrix Dreamworld You mean this isn’t real? – Neo† The Matrix is essentially a computer-generated dreamworld. It is the illusion of a world that no longer exists – a world of human technology and culture as it was at the end of the twentieth century. This illusion is pumped into the brains of millions of people who, in reality, are lying fast asleep in slime-filled cocoons. To them this virtual world seems like real life. They go to work, watch their televisions, and pay their taxes, fully believing that they are physically doing these things, when in fact they are doing them “virtually” – within their own minds. -

Bullet Time As Microgenre Author(S): Bob Rehak Source: Film Criticism, Vol

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Works The Migration of Forms: Bullet Time as Microgenre Author(s): Bob Rehak Source: Film Criticism, Vol. 32, No. 1, Special Issue on Digital Visual Effects and Popular Cinema (Fall, 2007), pp. 26-48 Published by: Allegheny College Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/24777382 Accessed: 08-05-2019 16:36 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms Allegheny College is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Film Criticism This content downloaded from 130.58.107.157 on Wed, 08 May 2019 16:36:11 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms The Migration of Forms: Bullet Time as Microgenre Bob Rehak Only minutes into The Matrix (Lany and Andy Wachowski, 1999), the movie unveils its money shot, as though aware the audience is impatient for it. Trinity (Carrie-Anne Moss), clad in skintight black leather, punctuates a brief, violent hotel room fight by spreading her arms, rising into the air, and lashing out in a kick that sends one of her policeman attackers flying. She moves with an impossible fluid weightlessness, as does the camera, which revolves around her while the hapless cops remain frozen. -

Facing the Absurd Existentialism for Humans and Programs

TWELVE 150 FACING THE ABSURD EXISTENTIALISM FOR HUMANS AND PROGRAMS The Matrix cannot tell you who you are. – Trinity†† Man is nothing else but what he makes of himself. Such is the first principle of existentialism. – Jean-Paul Sartre FACING THE ABSURD Of Gods and Architects Søren Kierkegaard, whose existentialist philosophy of faith was discussed in the previous chapter, requested that just two words be engraved on his tombstone at his death: THE INDIVIDUAL. This gesture nicely summarizes the main thrust of the existentialist movement in philosophy – which both begins and ends with the individual. Existentialism focuses on the issues that arise for us as separate and distinct persons who are, in a very profound sense, alone in the world. Its emphasis is on personal responsibility – on taking responsibility for who you are, what you do, and the meanings that you give to the world around you. While Kierkegaard’s existentialism was largely inspired by his religious commit- ments, atheism was the guiding assumption for many existentialist writers, includ- ing Martin Heidegger, Albert Camus, and Jean-Paul Sartre. In Existentialism as a Humanism, the French existentialist Jean-Paul Sartre explained how his philo- sophy was intimately tied to his atheism through the example of a paper-cutter. [H]ere is an object which has been made by an artisan whose inspiration came from a concept. He referred to the concept of what a paper-cutter is and likewise to a known method of production, which is part of the concept, something which by and large is a routine. Thus, the paper-cutter is at once an object produced in a certain way and, on the other hand, one having a specific use . -

The Matrix Trilogy's Postmodern Movie Messiah

Journal of Religion & Film Volume 9 Issue 2 October 2005 Article 7 October 2005 He is the One: The Matrix Trilogy's Postmodern Movie Messiah Mark D. Stucky [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf Recommended Citation Stucky, Mark D. (2005) "He is the One: The Matrix Trilogy's Postmodern Movie Messiah," Journal of Religion & Film: Vol. 9 : Iss. 2 , Article 7. Available at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf/vol9/iss2/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Religion & Film by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. He is the One: The Matrix Trilogy's Postmodern Movie Messiah Abstract Many films have used Christ figures to enrich their stories. In The Matrix trilogy, however, the Christ figure motif goes beyond superficial plot enhancements and forms the fundamental core of the three-part story. Neo's messianic growth (in self-awareness and power) and his eventual bringing of peace and salvation to humanity form the essential plot of the trilogy. Without the messianic imagery, there could still be a story about the human struggle in the Matrix, of course, but it would be a radically different story than that presented on the screen. This article is available in Journal of Religion & Film: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf/vol9/iss2/7 Stucky: He is the One Introduction The Matrix1 was a firepower-fueled film that spin-kicked filmmaking and popular culture. -

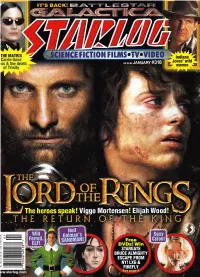

Starlog Magazine

THE MATRIX SCIENCE FICTION FILMS*TV*VIDEO Indiana Carrie-Anne 4 Jones' wild iss & the death JANUARY #318 r women * of Trinity Exploit terrain to gain tactical advantages. 'Welcome to Middle-earth* The journey begins this fall. OFFICIAL GAME BASED OS ''HE I.l'l't'.RAKY WORKS Of J.R.R. 'I'OI.KIKN www.lordoftherings.com * f> Sunita ft* NUMBER 318 • JANUARY 2004 THE SCIENCE FICTION UNIVERSE ^^^^ INSIDEiRicinE THISti 111* ISSUEicri ir 23 NEIL CAIMAN'S DREAMS The fantasist weaves new tales of endless nights 28 RICHARD DONNER SPEAKS i v iu tuuay jfck--- 32 FLIGHT OF THE FIREFLY Creator is \ 1 *-^J^ Joss Whedon glad to see his saga out on DVD 36 INDY'S WOMEN L/UUUy ICLdll IMC dLLIUII 40 GALACTICA 2.0 Ron Moore defends his plans for the brand-new Battlestar 46 THE WARRIOR KING Heroic Viggo Mortensen fights to save Middle-Earth 50 FRODO LIVES Atop Mount Doom, Elijah Wood faces a final test 54 OF GOOD FELLOWSHIP Merry turns grim as Dominic Monaghan joins the Riders 58 THAT SEXY CYLON! Tricia Heifer is the model of mocmodern mini-series menace 62 LANDniun OFAC THETUE BEARDEAD Disney's new animated film is a Native-American fantasy 66 BEING & ELFISHNESS Launch into space As a young man, Will Ferrell warfare with the was raised by Elves—no, SCI Fl Channel's new really Battlestar Galactica (see page 40 & 58). 71 KEYMAKER UNLOCKED! Does Randall Duk Kim hold the key to the Matrix mysteries? 74 78 PAINTING CYBERWORLDS Production designer Paterson STARLOC: The Science Fiction Universe is published monthly by STARLOG GROUP, INC., Owen 475 Park Avenue South, New York, NY 10016.