Stearic / Lauric Acid Mixtures As Phase Change Materials

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stearic Acid Acceptance Criteria: 194–212 Portions of This Monograph That Are National USP Text, and • C

Stage 6 Harmonization Official May 1, 2016 Stearic 1 L . = molecular weight of potassium hydroxide, Mr 56.11LNF34 Stearic Acid Acceptance criteria: 194±212 Portions of this monograph that are national USP text, and • C. The retention times of the major peaks of the Sample are not part of the harmonized text, are marked with solution correspond to those of the Standard solution, as N symbols ( .N) to specify this fact. obtained in the Assay. Octadecanoic acid; ASSAY Stearic acid [57-11-4]. • PROCEDURE DEFINITION Boron trifluoride±methanol solution: 140 g/L of bo- ron trifluoride in methanol Sample solution: Dissolve 100 mg of Stearic Acid in a Change to read: small conical flask fitted with a suitable reflux attach- ment with 5 mL of Boron trifluoride±methanol solution. Mixture consisting of stearic (octadecanoic) acid (C18H36O2; Boil under reflux for 10 min. Add 4.0 mL of heptane Mr, 284.5) and palmitic (hexadecanoic) acid (C16H32O2; through the condenser, and boil again under reflux for Mr, 256.4) obtained from fats or oils of vegetable or 10 min. Allow to cool. Add 20 mL of a saturated solu- animal origin. tion of sodium chloride. Shake, and allow the layers to Content: separate. Remove about 2 mL of the organic layer, and dry it over 0.2 g of anhydrous sodium sulfate. Dilute 1.0 mL of this solution with heptane to 10.0 mL. Stearic acid: 40.0%±60.0%. Sum of the Standard solution: Prepare as directed in the Sample contents of stearic acid and palmitic acids: solution using 50 mg of USP Stearic Acid RS and 50 mg Stearic acid 50 NLT 90.0%. -

Effects of Butter Oil Blends with Increased Concentrations of Stearic, Oleic and Linolenic Acid on Blood Lipids in Young Adults

European Journal of Clinical Nutrition (1999) 53, 535±541 ß 1999 Stockton Press. All rights reserved 0954±3007/98 $12.00 http://www.stockton-press.co.uk/ejcn Effects of butter oil blends with increased concentrations of stearic, oleic and linolenic acid on blood lipids in young adults CC Becker1, P Lund1, G Hùlmer1*, H Jensen2 and B SandstroÈm2 1Department of Biochemistry and Nutrition, Center for Food Research, Technical University of Denmark, Denmark; and 2Research Department of Human Nutrition, Center for Food Research, The Royal Veterinary and Agricultural University, Frederiksberg, Denmark Objective: The aim of this present project was to evaluate a more satisfactory effect on plasma lipoprotein pro®le of spreads based on dairy fat. Design: This study was designed as a randomised cross-over experiment with a three-week treatment separated by a three-week wash-out period. Sixty ®ve grams of the fat content of the habitual diets was replaced by either butter=grapeseed oil (90 : 10) (BG); butter oil and low erucic rapeseed oil (65 : 35) (BR) or butter blended in a 1 : 1 ratio with a interesteri®ed mixture of rapeseed oil and fully hydrogenated rapeseed oil (70 : 30) (BS). Subjects: Thirteen healthy free-living young men (age 21±26 y) ful®lled the study. Interventions: At the beginning and end of each diet period two venous blood samples were collected. Triacylglycerol and cholesterol concentrations in total plasma and VLDL, LDL, IDL and HDL fractions were measured, as were apo A-1 and apo B concentrations. Fatty acid composition of plasma phospholipids, plasma cholesterol ester and platelets was also determined. -

Oleochemicals Series

OLEOCHEMICALS FATTY ACIDS This section will concentrate on Fatty Acids produced from natural fats and oils (i.e. not those derived from petroleum products). Firstly though, we will recap briefly on Nomenclature. We spent some time clarifying the structure of oleochemicals and we saw how carbon atoms link together to form carbon chains of varying length (usually even numbered in nature, although animal fats from ruminant animals can have odd-numbered chains). A fatty acid has at least one carboxyl group (a carbon attached to two oxygens (-O) and a hydrogen (-H), usually represented as -COOH in shorthand) appended to the carbon chain (the last carbon in the chain being the one that the oxygen and hydrogen inhabit). We will only be talking about chains with one carboxyl group attached (generally called “monocarboxylic acids”). The acids can be named in many ways, which can be confusing, so we will try and keep it as simple as possible. The table opposite shows the acid designations as either the “length of the carbon chain” or the “common name”. While it is interesting to know the common name for a particular acid, we will try to use the chainlength in any discussion so you do not have to translate. Finally, it is usual to speak about unsaturated acids using their chainlength suffixed with an indication of the number of double bonds present. Thus, C16=1 is the C16 acid with one double bond; C18=2 is the C18 acid with two double bonds and so on. SELECTING RAW MATERIALS FOR FATTY ACID PRODUCTION In principle, fatty acids can be produced from any oil or fat by hydrolytic or lipolytic splitting (reaction with water using high pressure and temperature or enzymes). -

Fatty Acids: Structures and Introductory Article Properties Article Contents

Fatty Acids: Structures and Introductory article Properties Article Contents . Introduction Arild C Rustan, University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway . Overview of Fatty Acid Structure . Major Fatty Acids Christian A Drevon, University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway . Metabolism of Fatty Acids . Properties of Fatty Acids Fatty acids play a key role in metabolism: as a metabolic fuel, as a necessary component of . Requirements for and Uses of Fatty Acids in Human all membranes, and as a gene regulator. In addition, fatty acids have a number of industrial Nutrition uses. Uses of Fatty Acids in the Pharmaceutical/Personal Hygiene Industries Introduction doi: 10.1038/npg.els.0003894 Fatty acids, both free and as part of complex lipids, play a number of key roles in metabolism – major metabolic fuel (storage and transport of energy), as essential components subsequent one the b carbon. The letter n is also often used of all membranes, and as gene regulators (Table 1). In ad- instead of the Greek o to indicate the position of the double dition, dietary lipids provide polyunsaturated fatty acids bond closest to the methyl end. The systematic nomencla- (PUFAs) that are precursors of powerful locally acting ture for fatty acids may also indicate the location of double metabolites, i.e. the eicosanoids. As part of complex lipids, bonds with reference to the carboxyl group (D). Figure 2 fatty acids are also important for thermal and electrical outlines the structures of different types of naturally insulation, and for mechanical protection. Moreover, free occurring fatty acids. fatty acids and their salts may function as detergents and soaps owing to their amphipathic properties and the for- Saturated fatty acids mation of micelles. -

April 9, 2020 Replacement of Primex Brand Hydrogenated Vegetable

April 9, 2020 Replacement of Primex Brand Hydrogenated Vegetable Shortening In June of 2018 the FDA banned the use of trans fats in human foods. Due to the ban, Envigo was no longer able to source Primex brand hydrogenated vegetable oil (HVO) containing trans fats. Beginning on April 11th of 2018, Primex was replaced with an USP grade HVO made to a food-grade standard that has a similar texture and fatty acid profile (see table). Manufacturing tests revealed no appreciable differences in physical qualities of finished diets. Although diet numbers did not change, you may have noticed an updated diet title and ingredient description on the diet datasheet. Depending on your research goals and desire for relevance to human diets, you may wish to use a source of HVO without trans fats such as Crisco. Crisco is a proprietary HVO with minimal trans fats (see table). Envigo also offers several popular obesity inducing diets with alternate fat sources like lard or milkfat that may be suitable for your research. Contact a nutritionist to discuss alternate options. Comparison of the fatty acid profile of Primex, Envigo Teklad’s Replacement HVO and Crisco. Fatty Acids, % Primex HVO1 Replacement HVO2 Crisco3 Trans fatty acids 23.9 - 36.1 26 - 35.6 0.6 Saturated fatty acids 25.3 - 27.1 22.6 - 29.3 25.8 Monounsaturated fatty acids 25.3 - 33.3 24.8 - 32.6 18.7 Polyunsaturated fatty acids 5.6 - 9.0 7.1 - 9.4 49.5 16:0 palmitic acid 14.0 - 17.4 11.0 - 14.8 16.9 18:0 stearic acid 9.1 - 11.5 10.7 - 14.2 9.6 18:1 n9T elaidic acid 22.2 - 34.7 24.4 - 32.6 0 18:1 n9C oleic acid 16.6 - 26.5 17.2 - 25.7 18.1 18:1 n7C vaccenic acid 2.2 - 2.4 2.0 - 2.2 1.2 18:1 other cis isomers 6.3 - 7.8 6.1 - 6.7 0 18:2 n6 linoleic acid 5.8 - 9.1 7.0 - 9.2 44.8 18:2 other trans isomers 3.2 - 4.0 3.5 - 5.0 0.5 18:3 n3 linolenic acid 0.3 - 0.5 0.1 - 0.3 6.1 19:0 nonadecanoic acid 0.6 - 0.7 0.4 - 0.7 0 20:0 arachidic acid 0.3 - 0.4 0.4 0.4 1Range for Primex HVO represents the average ± 1 standard deviation (soybean and cottonseed or palm oil; n = 4). -

About Trans Fat and Partially Hydrogenated Oils Q. What Is Trans

About Trans Fat and Partially Hydrogenated Oils Q. What is trans fat? A. Most trans fat is a monounsaturated (one double bond) fatty acid. The shape of trans-fat molecules is more like cholesterol-raising saturated fat than a typical monounsaturated fatty acid. Perhaps for that reason, it increases cholesterol levels in blood and increases the risk of heart disease. Q. Where does trans fat come from? A. According to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), in 1994-96 we consumed about 5.6 grams of trans fat per day. Most of that trans fat comes from the 40,000-plus foods that contain partially hydrogenated vegetable oil. Those include many stick margarines, biscuits, pastries, cookies, crackers, icings, and deep-fried foods at restaurants. Because Frito-Lay, margarine producers, and some other companies recently stopped using (or cut back on the use of) partially hydrogenated oils, we now are consuming a little less trans fat. About one-fifth (1.2 g) of the trans fat came from natural sources, especially beef and milk products (bacteria in cattle produce trans fat that gets into meat and milk). A little more occurs naturally in vegetable oils and forms when vegetable oils are purified. Q. How is partially hydrogenated oil made? A. To convert soybean, cottonseed, or other liquid oil into a solid shortening, the oil is heated in the presence of hydrogen and a catalyst. That hydrogenation process converts some polyunsaturated fatty acids to monounsaturated and saturated fatty acids. It also converts some monounsaturated fatty acids to saturated fatty acids. Thus, a healthful oil is converted into a harmful one. -

Phase Diagrams of Fatty Acids As Biosourced Phase Change Materials for Thermal Energy Storage

applied sciences Article Phase Diagrams of Fatty Acids as Biosourced Phase Change Materials for Thermal Energy Storage Clément Mailhé 1,*, Marie Duquesne 2 , Elena Palomo del Barrio 3, Mejdi Azaiez 2 and Fouzia Achchaq 1 1 Université de Bordeaux, CNRS, I2M Bordeaux, Esplanade des Arts et Métiers, F-33405 Talence CEDEX, France; [email protected] 2 Bordeaux INP, CNRS, I2M Bordeaux, Esplanade des Arts et Métiers, F-33405 Talence CEDEX, France; [email protected] (M.D.); [email protected] (M.A.) 3 CIC EnergiGUNE, Parque Tecnológico de Álava, Albert Einstein, 48. Edificio CIC, 01510 Miñano, Álava, Spain; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 15 February 2019; Accepted: 6 March 2019; Published: 14 March 2019 Featured Application: A potential application of this work consists of accelerating the screening step required for the study and selection of promising binary systems of phase change materials for thermal energy storage at medium temperature. Abstract: Thermal energy storage is known as a key element to optimize the use of renewable energies and to improve building performances. Phase change materials (PCMs) derived from wastes or by-products of plant or animal oil origins are low-cost biosourced PCMs and are composed of more than 75% of fatty acids. They present paraffin-like storage properties and melting temperatures ranging from −23 ◦C to 78 ◦C. Therefore, they could be appropriate for latent heat storage technologies for building applications. Although already studied, a more detailed exploration of this class of PCMs is still required. In this frame, a screening of fatty acids and of their related binary systems must be performed. -

Omega-3, Omega-6 and Omega-9 Fatty Acids

Johnson and Bradford, J Glycomics Lipidomics 2014, 4:4 DOI: 0.4172/2153-0637.1000123 Journal of Glycomics & Lipidomics Review Article Open Access Omega-3, Omega-6 and Omega-9 Fatty Acids: Implications for Cardiovascular and Other Diseases Melissa Johnson1* and Chastity Bradford2 1College of Agriculture, Environment and Nutrition Sciences, Tuskegee University, Tuskegee, Alabama, USA 2Department of Biology, Tuskegee University, Tuskegee, Alabama, USA Abstract The relationship between diet and disease has long been established, with epidemiological and clinical evidence affirming the role of certain dietary fatty acid classes in disease pathogenesis. Within the same class, different fatty acids may exhibit beneficial or deleterious effects, with implications on disease progression or prevention. In conjunction with other fatty acids and lipids, the omega-3, -6 and -9 fatty acids make up the lipidome, and with the conversion and storage of excess carbohydrates into fats, transcendence of the glycome into the lipidome occurs. The essential omega-3 fatty acids are typically associated with initiating anti-inflammatory responses, while omega-6 fatty acids are associated with pro-inflammatory responses. Non-essential, omega-9 fatty acids serve as necessary components for other metabolic pathways, which may affect disease risk. These fatty acids which act as independent, yet synergistic lipid moieties that interact with other biomolecules within the cellular ecosystem epitomize the critical role of these fatty acids in homeostasis and overall health. This review focuses on the functional roles and potential mechanisms of omega-3, omega-6 and omega-9 fatty acids in regard to inflammation and disease pathogenesis. A particular emphasis is placed on cardiovascular disease, the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in the United States. -

Page 1 of 12Journal Name RSC Advances Dynamic Article Links ►

RSC Advances This is an Accepted Manuscript, which has been through the Royal Society of Chemistry peer review process and has been accepted for publication. Accepted Manuscripts are published online shortly after acceptance, before technical editing, formatting and proof reading. Using this free service, authors can make their results available to the community, in citable form, before we publish the edited article. This Accepted Manuscript will be replaced by the edited, formatted and paginated article as soon as this is available. You can find more information about Accepted Manuscripts in the Information for Authors. Please note that technical editing may introduce minor changes to the text and/or graphics, which may alter content. The journal’s standard Terms & Conditions and the Ethical guidelines still apply. In no event shall the Royal Society of Chemistry be held responsible for any errors or omissions in this Accepted Manuscript or any consequences arising from the use of any information it contains. www.rsc.org/advances Page 1 of 12Journal Name RSC Advances Dynamic Article Links ► Cite this: DOI: 10.1039/c0xx00000x www.rsc.org/xxxxxx ARTICLE TYPE Trends and demands in solid-liquid equilibrium of lipidic mixtures Guilherme J. Maximo, a,c Mariana C. Costa, b João A. P. Coutinho, c and Antonio J. A. Meirelles a Received (in XXX, XXX) Xth XXXXXXXXX 20XX, Accepted Xth XXXXXXXXX 20XX DOI: 10.1039/b000000x 5 The production of fats and oils presents a remarkable impact in the economy, in particular in developing countries. In order to deal with the upcoming demands of the oil chemistry industry, the study of the solid-liquid equilibrium of fats and oils is highly relevant as it may support the development of new processes and products, as well as improve those already existent. -

Physico-Chemical Analysis of Eight Samples of Elaeis Oleifera Oil Obtained from Different Nifor Oil Palm Fields

Research Journal of Food Science and Quality Control Vol. 3 No.1, 2017 ISSN 2504-6145 www.iiardpub.org Physico-Chemical Analysis of Eight Samples of Elaeis Oleifera Oil Obtained from Different Nifor Oil Palm Fields Dr. Winifred C. Udeh Medical Biochemistry Department, University of Port Harcourt, Port Harcourt [email protected] Dr. Jude Obibuzor Biochemistry Division, Nigerian institute for Oil palm Research Benin ABSTRACT Eight samples of Elaeis oleifera palm oil milled from fresh fruit bunches harvested from different NIFOR oil palm fields were analyzed to determine their physical and chemical properties in comparison to the properties of the normal palm oil Elaeis guineensis mainly milled by the institute. Analyses conducted included palatability test, determination of the free fatty acid values of the samples, determination of their peroxide values and their moisture contents. Results obtained showed evidences of disparity in chemical properties and slight physical differences between the two species of palm. The average free fatty acid value of the samples was 0.76% as against 0.85% of the normal Elaeis guineensis. Also, the average peroxide value of the samples was 3.83% meg/kg as against that of E. guineensis which was 4.26meg/kg while the average % moisture content of the samples was 0.47% and that of E. guineesis 0.51%. The iodine value (wijs) of the samples was 88.50 and that of E. guineensis 60.80. Beta-ketoacyl ACP synthase II enzyme activity were also determined in the sample and was 7.51 as against 2.15 in E. guineensis. The E. -

Cocoa Butter Equivalent (CBE) 29

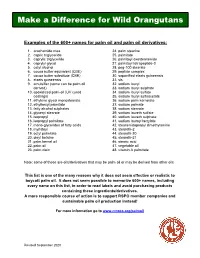

Make a Difference for Wild Orangutans Examples of the 600+ names for palm oil and palm oil derivatives: 1. arachamide mea 24. palm stearine 2. capric triglyceride 25. palmitate 3. caprylic triglyceride 26. palmitoyl oxostearamide 4. caprylyl glycol 27. palmitoyl tetrapeptide-3 5. cetyl alcohol 28. peg-100 stearate 6. cocoa butter equivalent (CBE) 29. peptide complex 7. cocoa butter substitute (CBE) 30. saponified elaeis guineensis 8. elaeis guineensis 31. sls 9. emulsifier (some can be palm oil 32. sodium lauryl derived) 33. sodium lauryl sulphate 10. epoxidized palm oil (UV cured 34. sodium lauryl sulfate coatings) 35. sodium lauryl sulfoacetate 11. ethylene glycol monostearate 36. sodium palm kernelate 12. ethylhexyl palmitate 37. sodium palmate 13. fatty alcohol sulphates 38. sodium stearate 14. glyceryl stearate 39. sodium laureth sulfate 15. isopropyl 40. sodium laureth sulphate 16. isopropyl palmitate 41. sodium lauroyl lactylate 17. mono-glycerides of fatty acids 42. stearamidopropyl dimethylamine 18. myristoyl 43. steareth-2 19. octyl palmitate 44. steareth-20 20. oleyl betaine 45. steareth-21 21. palm kernel oil 46. stearic acid 22. palm oil 47. vegetable oil 23. palm olein 48. vitamin A palmitate Note: some of these are oils/derivatives that may be palm oil or may be derived from other oils This list is one of the many reasons why it does not seem effective or realistic to boycott palm oil. It does not seem possible to memorize 600+ names, including every name on this list, in order to read labels and avoid purchasing products containing these ingredients/derivatives. A more responsible course of action is to support RSPO member companies and sustainable palm oil production instead! For more information go to www.cmzoo.org/palmoil Revised September 2020 . -

PROVISIONAL PEER REVIEWED TOXICITY VALUES for OCTADECANOIC ACID (STEARIC ACID, CASRN 57-11-4) Derivation of Subchronic and Chronic Oral Rfds

EPA/690/R-04/012F l Final 12-21-2004 Provisional Peer Reviewed Toxicity Values for Octadecanoic Acid (Stearic Acid) (CASRN 57-11-4) Derivation of Subchronic and Chronic Oral RfDs Superfund Health Risk Technical Support Center National Center for Environmental Assessment Office of Research and Development U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Cincinnati, OH 45268 Acronyms and Abbreviations bw body weight cc cubic centimeters CD Caesarean Delivered CERCLA Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation and Liability Act of 1980 CNS central nervous system cu.m cubic meter DWEL Drinking Water Equivalent Level FEL frank-effect level FIFRA Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act g grams GI gastrointestinal HEC human equivalent concentration Hgb hemoglobin i.m. intramuscular i.p. intraperitoneal i.v. intravenous IRIS Integrated Risk Information System IUR inhalation unit risk kg kilogram L liter LEL lowest-effect level LOAEL lowest-observed-adverse-effect level LOAEL(ADJ) LOAEL adjusted to continuous exposure duration LOAEL(HEC) LOAEL adjusted for dosimetric differences across species to a human m meter MCL maximum contaminant level MCLG maximum contaminant level goal MF modifying factor mg milligram mg/kg milligrams per kilogram mg/L milligrams per liter MRL minimal risk level i MTD maximum tolerated dose MTL median threshold limit NAAQS National Ambient Air Quality Standards NOAEL no-observed-adverse-effect level NOAEL(ADJ) NOAEL adjusted to continuous exposure duration NOAEL(HEC) NOAEL adjusted for dosimetric differences across