From Women's Hands: an Object Biography of the Mctavish Collection

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A New Look at the Himalayan Fur Trade

ORYX VOL 27 NO 4 OCTOBER 1993 A new look at the Himalayan fur trade Joel T. Heinen and Blair Leisure In late December 1991 and January 1992 the authors surveyed tourist shops sell- ing fur and other animal products in Kathmandu, Nepal. Comparing the results with a study conducted 3 years earlier showed that the number of shops had in- creased, but indirect evidence suggested that the demand for their products may have decreased. There was still substantial trade in furs, most of which appeared to have come from India, including furs from species that are protected in India and Nepal. While both Nepali and Indian conservation legislation are adequate to con- trol the illegal wildlife trade, there are problems in implementation: co-ordination between the two countries, as well as greater law enforcement within each country, are needed. Introduction Enforcement of conservation legislation Since the 1970s Nepal and India have been In spite of measurable successes with regard considered to be among the most progressive to wildlife conservation, there are several ob- of developing nations with regard to legis- stacles to effective law enforcement in both lation and implementation of wildlife conser- countries. In Nepal the Department of vation programmes. The Wildlife (Protection) National Parks and Wildlife Conservation Act of India was passed in 1972 (Saharia and (DNPWC), which is the designated manage- Pillai, 1982; Majupuria 1990a), and Nepal's ment authority of CITES (Fitzgerald, 1989; National Park and Wildlife Conservation Act Favre, 1991), is administratively separate from was passed in 1973 (HMG, 1977). Both have the Department of Forestry, but both depart- schedules of fully protected species, including ments are within the Ministry of Forests and many large mammalian carnivores and other the Environment. -

The Fur Trade of the Western Great Lakes Region

THE FUR TRADE OF THE WESTERN GREAT LAKES REGION IN 1685 THE BARON DE LAHONTAN wrote that ^^ Canada subsists only upon the Trade of Skins or Furrs, three fourths of which come from the People that live round the great Lakes." ^ Long before tbe little French colony on tbe St. Lawrence outgrew Its swaddling clothes the savage tribes men came in their canoes, bringing with them the wealth of the western forests. In the Ohio Valley the British fur trade rested upon the efficacy of the pack horse; by the use of canoes on the lakes and river systems of the West, the red men delivered to New France furs from a country unknown to the French. At first the furs were brought to Quebec; then Montreal was founded, and each summer a great fair was held there by order of the king over the water. Great flotillas of western Indians arrived to trade with the Europeans. A similar fair was held at Three Rivers for the northern Algonquian tribes. The inhabitants of Canada constantly were forming new settlements on the river above Montreal, says Parkman, ... in order to intercept the Indians on their way down, drench them with brandy, and get their furs from them at low rates in ad vance of the fair. Such settlements were forbidden, but not pre vented. The audacious " squatter" defied edict and ordinance and the fury of drunken savages, and boldly planted himself in the path of the descending trade. Nor is this a matter of surprise; for he was usually the secret agent of some high colonial officer.^ Upon arrival in Montreal, all furs were sold to the com pany or group of men holding the monopoly of the fur trade from the king of France. -

A New Challenge to the Fur Trade

VOLUME XXXV NO. 2 SPRING 2015 Enter the Americans: A New Challenge to the Fur Trade hile the American entry into the the fur trade in what was to become W fur trade market west of the the Louisiana Purchase (1803) Mississippi River was rather late in its continued unabated to supply the history, it was never the less significant demand in Europe. in many ways. Preceding them by over Trade Goods two hundred years were the Dutch, th Spanish, French, and British trappers From the 13 century onwards the who had several generations of dealing colored glass trade beads found with the Native Americans in the throughout the world were northeast, the Great Lakes region, the manufactured in Venice, Italy. By the upper Missouri area, and the Pacific 1600s glass beads were also being Northwest, as well as the southwestern created in Bohemia (Czech Republic), part of what became the United States. Holland, France, England, and Sweden. The North American continent (and For a short while there was even a to a lesser extent South America) had bead-making industry at Jamestown, long been a source of raw materials for the various, Virginia. Many styles and colors were manufactured, ever-changing, empires of Europe whose resources with different tribes valuing different colors and in timber and furs had been depleted. Looking west designs and trading accordingly. they found a land rich in the many products they Other trade goods made of metal created a needed: timber for ship-building, pelts for the substantial industry throughout Europe, supplying fashions of the moment, and hides for the leather the growing Indian demand for improved substitutes belts that turned the factory wheels of industry. -

Adventures on the American Frontier Pioneer Traders Part Three Manuel Lisa on the Missouri River

Adventures on the American Frontier Pioneer Traders Part Three Manuel Lisa on the Missouri River A Royal Fireworks Production Royal Fireworks Press Unionville, New York George Croghan, Fur Trader Trader Kinzie and the Battle of Fort Dearborn Joe LaBarge, Missouri River Boy The Bent Brothers on the Santa Fe Trail OtherAbe books Lincoln, in thisTrader series: This book features QR codes that link to audio of the book being narrated so that readers can follow along. Copyright © 2020, Royal Fireworks Online Learning, Inc. All Rights Reserved. Royal Fireworks Press P.O. Box 399 41 First Avenue Unionville, NY 10988-0399 (845) 726-4444 fax: (845) 726-3824 email: [email protected] website: rfwp.com ISBN: 978-0-89824-783-1 Printed and bound in Unionville, New York, on acid-free paper using vegetable-based inks at the Royal Fireworks facility. Publisher: Dr. T.M. Kemnitz Editor: Jennifer Ault Book and cover designer: Christopher Tice Audio and narration: Christopher Tice 10Jun20 Traders bringing furs by boat to New Orleans (whatever it looked like in 1760, which is probably not much like now at all) During the French and Indian War, the fighting to the north and east didn’t much bother the people in the old French city of New Orleans. Their fur traders were bringing rich catches down the Mississippi River, and that hadn’t stopped with the war. 1 Because the fur trade was so good for the traders coming down the Missouri River into the Mississippi River, the traders decided to open a new trading post farther north, near the place where the Missouri River flows into the Mississippi. -

The Fur Trade Era, 1770S–1849

Great Bear Rainforest The Fur Trade Era, 1770s–1849 The Fur Trade Era, 1770s–1849 The lives of First Nations people were irrevocably changed from the time the first European visitors came to their shores. The arrival of Captain Cook heralded the era of the fur trade and the first wave of newcomers into the future British Columbia who came from two directions in search of lucrative pelts. First came the sailors by ship across the Pacific Ocean in pursuit of sea otter, then soon after came the fort builders who crossed the continent from the east by canoe. These traders initiated an intense period of interaction between First Nations and European newcomers, lasting from the 1780s to the formation of the colony of Vancouver Island in 1849, when the business of trade was the main concern of both parties. During this era, the newcomers depended on First Nations communities not only for furs, but also for services such as guiding, carrying mail, and most importantly, supplying much of the food they required for daily survival. First Nations communities incorporated the newcomers into the fabric of their lives, utilizing the new trade goods in ways which enhanced their societies, such as using iron to replace stone axes and guns to augment the bow and arrow. These enhancements, however, came at a terrible cost, for while the fur traders brought iron and guns, they also brought unknown diseases which resulted in massive depopulation of First Nations communities. European Expansion The northwest region of North America was one of the last areas of the globe to feel the advance of European colonialism. -

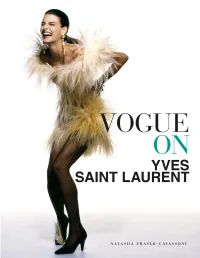

Vogue on Yves Saint Laurent

Model Carrie Nygren in Rive Gauche’s black double-breasted jacket and mid-calf skirt with long- sleeved white blouse; styled by Grace Coddington, photographed by Guy Bourdin, 1975. Linda Evangelista wears an ostrich-feathered couture slip dress inspired by Saint Laurent’s favourite dancer, Zizi Jeanmaire. Photograph by Patrick Demarchelier, 1987. At home in Marrakech, Yves Saint Laurent models his new ready-to-wear line, Rive Gauche Pour Homme. Photograph by Patrick Lichfield, 1969. DIOR’S DAUPHIN FASHION’S NEW GENIUS A STYLE REVOLUTION THE HOUSE THAT YVES AND PIERRE BUILT A GIANT OF COUTURE Index of Searchable Terms References Picture credits Acknowledgments “CHRISTIAN DIOR TAUGHT ME THE ESSENTIAL NOBILITY OF A COUTURIER’S CRAFT.” YVES SAINT LAURENT DIOR’S DAUPHIN n fashion history, Yves Saint Laurent remains the most influential I designer of the latter half of the twentieth century. Not only did he modernize women’s closets—most importantly introducing pants as essentials—but his extraordinary eye and technique allowed every shape and size to wear his clothes. “My job is to work for women,” he said. “Not only mannequins, beautiful women, or rich women. But all women.” True, he dressed the swans, as Truman Capote called the rarefied group of glamorous socialites such as Marella Agnelli and Nan Kempner, and the stars, such as Lauren Bacall and Catherine Deneuve, but he also gave tremendous happiness to his unknown clients across the world. Whatever the occasion, there was always a sense of being able to “count on Yves.” It was small wonder that British Vogue often called him “The Saint” because in his 40-year career women felt protected and almost blessed wearing his designs. -

Of Fur and Fins: Quantifying Fur Trade Era Fish Harvest to Assess Changes in Contemporary Lake Whitefish (Coregonus Clupeaformis) Production at Lac La Biche, Alberta

Journal of Ecological Anthropology Volume 16 Issue 1 Volume 16, Issue 1 (2013) Article 1 1-1-2013 Of Fur and Fins: Quantifying Fur Trade Era Fish Harvest to Assess Changes in Contemporary Lake Whitefish (Coregonus clupeaformis) Production at Lac La Biche, Alberta Andrea M. McGregor Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/jea Recommended Citation McGregor, Andrea M.. "Of Fur and Fins: Quantifying Fur Trade Era Fish Harvest to Assess Changes in Contemporary Lake Whitefish (Coregonus clupeaformis) Production at Lac La Biche, Alberta." Journal of Ecological Anthropology 16, no. 1 (2013): 5-26. Available at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/jea/vol16/iss1/1 This Research Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Anthropology at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Ecological Anthropology by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. McGregor / Historic Fish Harvest Changes ARTICLES Of Fur and Fins: Quantifying Fur Trade Era Fish Harvest to Assess Changes in Contemporary Lake Whitefish (Coregonus clupeaformis) Production at Lac La Biche, Alberta Andrea M. McGregor ABSTracT The history of fisheries exploitation in Canada has significant ties to the development and westward expansion of the fur trade. Understanding the scale and nature of this relationship is important when assessing the develop- mental or evolutionary history of a system. This study uses estimates of human population size and subsistence lake whitefish (Coregonus clupeaformis) consumption to estimate annual fish harvest at Lac la Biche, Alberta (54o52'N, 112o05'W) during the fur trade era and to assess the magnitude and potential influence of historic harvest on contemporary harvest potential. -

The Reality of Commercial Rabbit Farming in Europe

The reality of commercial rabbit farming in Europe Coalition to abolish the fur trade www.caft.org.uk www.rabbitfur.info mail:[email protected] he rabbit fur trade is the fastest growing section of the industry, yet little is publicly Tknown about it. Many myths have been perpetuated about this industry, thus allowing the fur trade to increase the popularity of rabbit fur. Because of this, the Coalition to abolish the Fur Trade (CAFT) planned an investigation to conduct research into the industry and obtain video and photographic evidence. CAFT investigators travelled to four European countries – Denmark, Spain, Italy and France – to investigate all aspects of the trade. It was vital to look into the rabbit farming industry as a whole: Italy including farms which breed rabbits specifically for the fur During the 1970s, the rabbit farming industry in Italy was very trade, farms for rabbit meat production, slaughterhouses, much a cottage industry. Due to the demand for rabbit meat, dressing companies, and companies which explore the genetic the industry grew steadily to reach almost twice its size in breeding of rabbits for both fur and meat. 2003 (222,000 TEC); Italy consumes most of the meat it produces and imports are low. The greatest concentration and the largest farms are found in northern Italy (Veneto, SIZE OF INDUSTRY Lombardia, Emilia-Romagna and Piemonte regions) where farms are large and intensive (500-1,000 does). Production is, There appears to be no reliable figures for commercial rabbit nonetheless, substantial throughout the country: In central and farming today; the last figures are from 2003 when the southern Italy there are a large number of medium and small 5 European Food Safety Authority commissioned a scientific sized farms (100-500 does). -

Fur Trade in the UK

House of Commons Environment, Food and Rural Affairs Committee Fur trade in the UK Seventh Report of Session 2017–19 Report, together with formal minutes relating to the report Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 18 July 2018 HC 823 Published on 22 July 2018 by authority of the House of Commons The Environment, Food and Rural Affairs Committee The Environment, Food and Rural Affairs Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to examine the expenditure, administration and policy of the Department of Environment, Food and Rural Affairs and associated public bodies. Current membership Neil Parish MP (Conservative, Tiverton and Honiton) (Chair) Alan Brown MP (Scottish National Party, Kilmarnock and Loudoun) Paul Flynn MP (Labour, Newport West) John Grogan MP (Labour, Keighley) Dr Caroline Johnson MP (Conservative, Sleaford and North Hykeham) Kerry McCarthy MP (Labour, Bristol East) Sandy Martin MP (Labour, Ipswich) Mrs Sheryll Murray MP (Conservative, South East Cornwall) David Simpson MP (Democratic Unionist Party, Upper Bann) Angela Smith MP (Labour, Penistone and Stocksbridge) Julian Sturdy MP (Conservative, York Outer) Powers The Committee is one of the departmental select committees, the powers of which are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No 152. These are available on the Internet via www.parliament.uk. Publications Committee reports are published on the Committee’s website at www.parliament.uk/efracom and in print by Order of the House. Evidence relating to this report is published on the inquiry publications page of the Committee’s website. Committee staff The current staff of the Committee are Eliot Barrass (Clerk), Sian Woodward (Clerk), Daniel Schlappa (Second Clerk), Xameerah Malik (Senior Committee Specialist), Andy French (Committee Specialist), Anwen Rees (Committee Specialist), James Hockaday (Senior Committee Assistant), Ian Blair (Committee Assistant) and Annabel Russell (Committee Assistant). -

The Russian Fur Trade and Industry

Julia Gibson Russia and the Environment Professors McKinney and Welsh Final Paper May 9th 2006 The Russian Fur Trade and Industry People have utilized the skin and fur of animals to keep warm since the prehistoric era of human history. As human beings left the equatorial regions where Homo sapiens evolved, the severity of colder climates forced them to protect their uncovered bodies with the pelts of regional animals that were better adapted to the harsh environment. The exploitation of pelts probably arose as a result of the invention of simple tools, which enabled people to separate the meat for cooking and the fur for wearing. As human civilization advanced, those human societies dependant on fur for warmth also began to utilize animal fur and skin as a luxury item. Communities like the ancient state of Rus flourished and grew in importance in cross continental trade due to the natural abundance of fur-bearing animals in their territories. Despite the growing environmental damage and the suffering of animals harvested for fur, the fur trade and industry gained increasing importance over the centuries. Throughout the history of Russia (including the Soviet Union), the fur trade has enabled the Russian state to pursue the doctrine of Moscow as the third Rome and bolster their economy, while simultaneously and systematically distancing the Russian people from the environment and severing their connection with the natural world. Even before the fur trade became a crucial component of the Russian economy, the practice of exchanging furs played an integral part in traditional Russian culture. The 1 use of pelts in ancient Shamanistic rituals established fur as a semi-spiritual commodity. -

AN ABSTRACT of the THESIS of Jennifer E. Jameson for the Degree

AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Jennifer E. Jameson for the degree of Master of Arts in Interdisciplinary Studies in Anthropology , Design and Human Environment , and Anthropology presented on December 5, 2007 . Title: Iroquois of the Pacific Northwest Fur Trade: Their Archaeology and History Abstract approved: ___________________________ David R. Brauner During the early 19 th Century, the fur trade brought many Iroquois to the Pacific Northwest as working primarily as voyageurs for the North West Company. When the North West Company merged with the Hudson’s Bay Company, the Iroquois employees merged as well. After retirement, some settled in the Willamette Valley and surrounding areas. These Iroquois have been an underrepresented group in the Pacific Northwest history. When archaeological investigations are completed, the Iroquois are overlooked as possible occupants. The purpose of this research is to reconstruct the history of the Iroquois and to create an archaeological description of what their material culture might look like in the Pacific Northwest. Theories involving ethnicity in archaeology, along with documentary evidence and archaeological data, were used to complete body of knowledge that brings the Pacific Northwest Iroquois story to light, and create a catalog of the ethnic markers for archaeologists to look for. ©Copyright by Jennifer E. Jameson December 5, 2007 All Rights Reserved Iroquois of the Pacific Northwest Fur Trade: Their Archaeology and History by Jennifer E. Jameson A THESIS submitted to Oregon State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Interdisciplinary Studies Presented December 5, 2007 Commencement June 2008 Master of Arts in Interdisciplinary Studies thesis of Jennifer E. -

^ 1934 Rae and Raymond

THE GLENGARRY NEWS ALBXAJSTDRIA, ONT, FRIDAY. DECEMBER 22, 1933. VOL. XLI-4^0. 52. $2.00 A YEAR Sbgarry’s Second Rev. A. L FAcDonalil Onlario's legislature Te Peace On Earth Mr. Jes. J. Aeeneilf Corewall Hauers Aeges 1. Mclaughlin Celebrates His Silver Jubilee Open January 31$t For a short space 'Of time the whirl- Feriuer Gteegarrian Passes . Annual Seed Fair ^ ing storm of words is hush^ and we Sir Arllrer Currie Hies AI livingsten, Meet. As annoTiiieed previously the Glen- On Thursday morning of last week. ^ Toronto, December 19.— The fifth speak the sentences which convey the Joseph J. Kennedy, resident of Ash- In common with eVery city and town (The Livingston Enterprise, Dec 6) garry Plowmen ^8 Association are tin- Dee. I4th,. Rev. Alexander L. McDon- an(j last session of the 18th Legis- kindly sent'ments of the season asso- land,, Wisconsin for over 40 years and ' in Canada where a branch of the Angus Ii. McLaughlin, pioneer con- dertaking once again the task of put- ald, P.P. o!£l Sft, Mary's, WilUaras- lature of Ontario will open January ciated with^ the coming of the Prince a member of the Chequamegon Bay Canadian Legion of the B.E.S.L. is tiaetor of Park county^ was called by ting on a “Seed Pair”. This Exhibi- town and St. William’s Chapel Mar- 31 Premier George S. Henry announc- of Peace. Few years have heard so. Old Settlers’ Club passed away Sun located members of the Canadian Le- death at his - home on West Geyser tion will be held at Alexandria, on the tintown,observed the silver jubilee of ed today'following decision of the Cab- many words uttered, about the past day, October at the home of his gion ofl Cornwall held a memorial ser- street, Tuesday afternoon 5th inst, 17th and 18th of January.