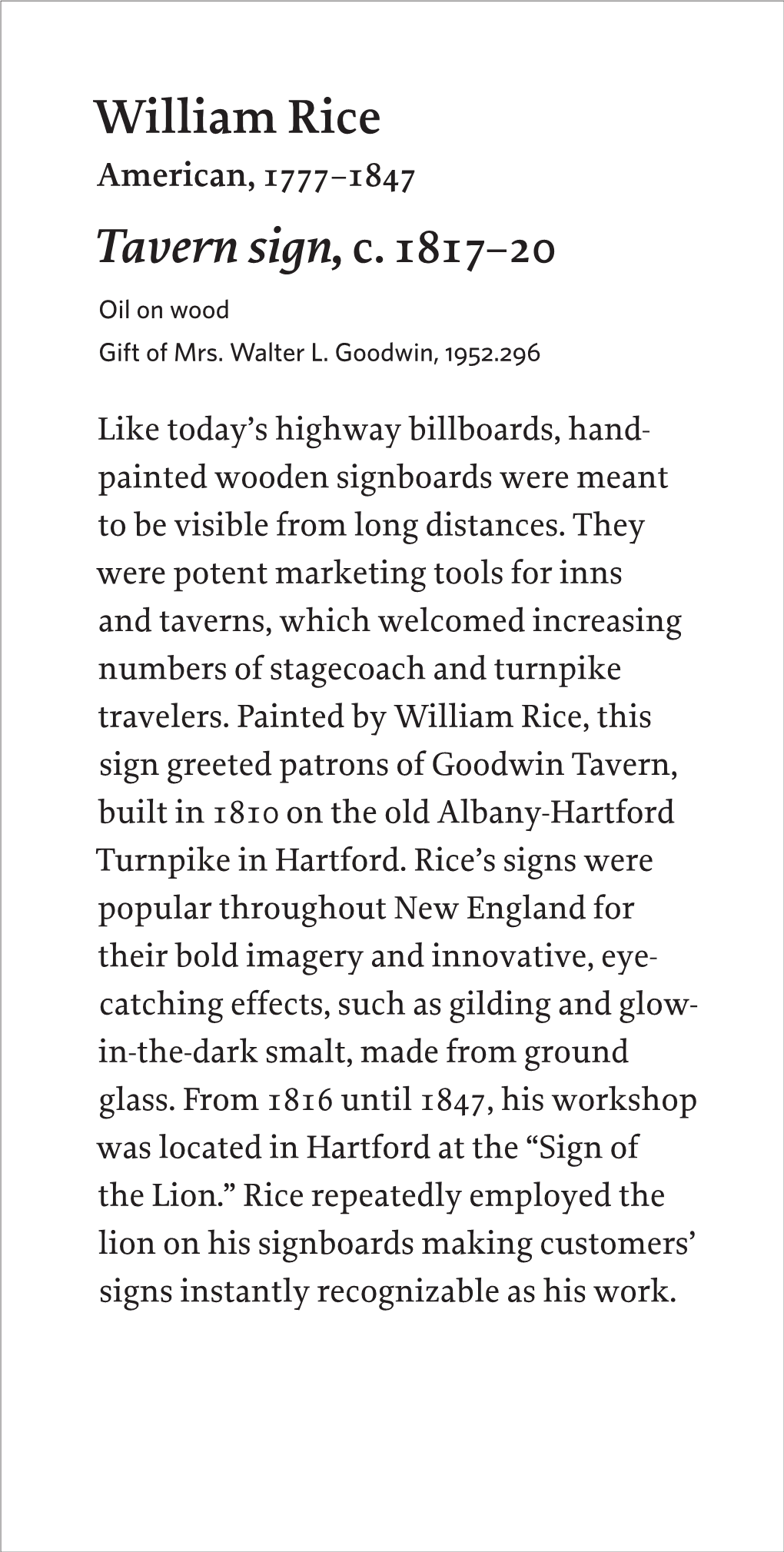

William Rice Tavern Sign, C. 1817–20

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Historic Furnishings Assessment, Morristown National Historical Park, Morristown, New Jersey

~~e, ~ t..toS2.t.?B (Y\D\L • [)qf- 331 I J3d-~(l.S National Park Service -- ~~· U.S. Department of the Interior Historic Furnishings Assessment Morristown National Historical Park, Morristown, New Jersey Decemb r 2 ATTENTION: Portions of this scanned document are illegible due to the poor quality of the source document. HISTORIC FURNISHINGS ASSESSMENT Ford Mansion and Wic·k House Morristown National Historical Park Morristown, New Jersey by Laurel A. Racine Senior Curator ..J Northeast Museum Services Center National Park Service December 2003 Introduction Morristown National Historical Park has two furnished historic houses: The Ford Mansion, otherwise known as Washington's Headquarters, at the edge of Morristown proper, and the Wick House in Jockey Hollow about six miles south. The following report is a Historic Furnishings Assessment based on a one-week site visit (November 2001) to Morristown National Historical Park (MORR) and a review of the available resources including National Park Service (NPS) reports, manuscript collections, photographs, relevant secondary sources, and other paper-based materials. The goal of the assessment is to identify avenues for making the Ford Mansion and Wick House more accurate and compelling installations in order to increase the public's understanding of the historic events that took place there. The assessment begins with overall issues at the park including staffing, interpretation, and a potential new exhibition on historic preservation at the Museum. The assessment then addresses the houses individually. For each house the researcher briefly outlines the history of the site, discusses previous research and planning efforts, analyzes the history of room use and furnishings, describes current use and conditions, indicates extant research materials, outlines treatment options, lists the sources consulted, and recommends sourc.es for future consultation. -

JC-Catalogue-Cabinetry.Pdf

jonathan charles fine furniture • cabinetry & beds catalogue • volume 1 volume • furniture fine cabinetry • & beds catalogue jonathan charles USA & CANADA 516 Paul Street, P.O. Box 672 Rocky Mount, NC.27802, United States t 001-252-446-3266 f 001-252-977-6669 [email protected] HIGH POINT SHOWROOM chests of drawers • bookcases, bookshelves & étagères • cabinets • beds 200 North Hamilton Building 350 Fred Alexander Place High Point, NC.27260, United States t 001-336-889-6401 UK & EUROPE Unit 6c, Shortwood Business Park Dearne Valley Park Way, Hoyland South Yorkshire, S74 9LH, United Kingdom t +44 (0)1226 741 811 & f +44 (0)1226 744 905 Cabinetry Beds [email protected] j o n a t h a n c h a r l e s . c o m printed in china It’s all in the detail... CABINETRY & BEDS JONATHAN CHARLES CABINETRY & BEDS CATALOGUE VOL.1 CHESTS OF DRAWERS 07 - 46 BOOKCASES, BOOKSHELVES... 47 - 68 CABINETS 69 - 155 BEDS 156 - 164 JONATHANCHARLES.COM CABINETRY & BEDS Jonathan Charles Fine Furniture is recognised as a top designer and manufacturer of classic and period style furniture. With English and French historical designs as its starting point, the company not only creates faithful reproductions of antiques, but also uses its wealth of experience to create exceptional new furniture collections – all incorporating a repertoire of time- honoured skills and techniques that the artisans at Jonathan Charles have learned to perfect. Jonathan Charles Fine Furniture was established by Englishman Jonathan Sowter, who is both a trained cabinet maker and teacher. Still deeply involved in the design of the furniture, as well as the direction of the business, Jonathan oversees a skilled team of managers and craftspeople who make fine furniture for discerning customers around the world. -

The Dining Room

the Dining Room Celebrate being together in the room that is the heart of what home is about. Create a space that welcomes you and your guest and makes each moment a special occasion. HOOKER® FURNITURE contents 4 47 the 2 Adagio 4 Affinity New! dining room 7 American Life - Roslyn County New! Celebrate being together with dining room furniture from Hooker. Whether it’s a routine meal for two “on the go” 12 American Life - Urban Elevation New! between activities and appointments, or a lingering holiday 15 Arabella feast for a houseful of guests, our dining room collections will 19 Archivist enrich every occasion. 23 Auberose From expandable refectory tables to fliptop tables, we have 28 Bohéme New! a dining solution to meet your needs. From 18th Century European to French Country to Contemporary, our style 32 Chatelet selection is vast and varied. Design details like exquisite 35 Corsica veneer work, shaped fronts, turned legs and planked tops will 39 Curata lift your spirits and impress your guests. 42 Elixir Just as we give careful attention to our design details, we 44 Hill Country also give thought to added function in our dining pieces. Your meal preparation and serving will be easier as you take 50 Leesburg advantage of our wine bottle racks, flatware storage drawers 52 Live Edge and expandable tops. 54 Mélange With our functional and stylish dining room selections, we’ll 56 Pacifica New! help you elevate meal times to memorable experiences. 58 Palisade 64 Sanctuary 61 Rhapsody 72 Sandcastle 76 Skyline 28 79 Solana 82 Sorella 7 83 Studio 7H 86 Sunset Point 90 Transcend 92 Treviso 95 True Vintage 98 Tynecastle 101 Vintage West 104 Wakefield 106 Waverly Place 107 Dining Tables 109 Dining Tables with Added Function 112 Bars & Entertaining 116 Dining Chairs 124 Barstools & Counter Stools 7 132 Index & Additional Information 12 1 ADAGIO For more information on Adagio items, please see index on page 132. -

Cattails Beginning-Year Edition

cattails January 2015 cattails January 2015 Contents ________________________________________________________________________ Editor's Prelude • Contributors • Haiku Pages • Haibun Pages • Haiga & Tankart Page • Senryu Pages • Tanka Pages • Tanka Translation Page • Youth Corner Page • UHTS Contest Winners • Pen this Painting Page • Book Review Pages • Featured Poet Page • cAt taLes Cartoons • Ark and Apple Videos • not included in PDF archive White Page • Spotlight Feature Page • Artist Showcase Page • FAQ Page • Not included on this page of cattails are other subjects over on the UHTS Main Website like: What to submit, How to submit, contest info, How to Join, to see the last e-News Bulletin, learn about the UHTS Officers and Support Team, visit the Archives view our Members List, the Calendar, and other information, please revisit the UHTS Main Website cattails January 2015 cattails January 2015 Principal Editor's Prelude ____________________________________________________________ Happy International Haibun Month from the UHTS A very warm welcome to our 2015 edition of cattails collected works of the UHTS, and a very happy new year. There were a record number of submissions received for this edition (1,272), albeit only 387 were accepted for publication. Our membership has risen to over 400 people now and is still going strong each and every day. Please keep passing the word to your peers and friends, as we plan to soon become the largest international and most cohesive poetry society of its kind in the world. When choosing work for publication, as principal editor of cattails, I look for Japanese style short forms that have been composed firstly and quietly considerate of sophisticated literary works that reflect the natural world through poetic beauty of thought. -

Cheney Brothers, the New York Connection

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings Textile Society of America 1998 Cheney Brothers, the New York Connection Carol Dean Krute Wadsworth Atheneum Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf Part of the Art and Design Commons Dean Krute, Carol, "Cheney Brothers, the New York Connection" (1998). Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings. 183. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf/183 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Textile Society of America at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Cheney Brothers, the New York Connection Carol Dean Krute Wadsworth Atheneum The Cheney Brothers turned a failed venture in seri-culture into a multi-million dollar silk empire only to see it and the American textile industry decline into near oblivion one hundred years later. Because of time and space limitations this paper is limited to Cheney Brothers' activities in New York City which are, but a fraction, of a much larger story. Brothers and beginnings Like many other enterprising Americans in the 1830s, brothers Charles (1803-1874), Ward (1813-1876), Rush (1815-1882), and Frank (1817-1904), Cheney became engaged in the time consuming, difficul t business of raising silk worms until they discovered that speculation on the morus morticaulis, the white mulberry tree upon which the worms fed, might be far more profitable. As with all high profit operations the tree business was a high-risk venture, throwing many investors including the Cheney brothers, into bankruptcy. -

Southwest-Indian-Catalog-20210806

A A A THREE-STRAND HEISHI SHELL AND A Americana Collection A WALK IN BEAUTY CAP TURQUOISE CHOKER NECKLACE C With its bold shapes of turquoise, this three- Fitted, relaxed and curved with embroidered Add casual ease and a patriotic flair to your summer strand necklace featuring warm hues of shell Lavender and “Walk in Beauty “ logo on front. wardrobe with these cotton tanks and tunics in red, heishi will add a flair of the natural world to Made from garment washed cotton twill. your look. Certain to elevate your look, be it white and blue, each with a colorful “watercolor” of an (One Size, Adjustable ) #16032 $25 casual or dressy. Silver clasp. 16” idyllic American farm scene featuring the Stars and Stripes. B GARDEN LOVER LAVENDER #6154 $119 A TURQUOISE TRIANGLE & A TUNIC STYLE COTTON CONCHA TOP EARRINGS Pretty long sleeve scoop-neck tunic featuring lovely B HEISHI SHELL & TURQUOISE EARRINGS Silver concha with dangling C watercolor print perfect for the gardener or lover 2¼” loop dangle earrings featuring natural pressed composite Turquoise. AMERICANA TANK of lavender. Comfy and soft, A great gift for Mom! B white and gray shells and contrasting (100% Cotton) (S, M, L, XL, 2X, 3X) #6172 $89 #8675 (S-M-L-XL-1X-2X-3X) $59 turquoise. Each pair is one-of-a-kind! A #8684 RED Father & Daughter $49 #6155 $69 B TURQUOISE TRIANGLE & WHITE Farm, Truck & Wildflowers B #8685 $49 C FLORAL EMBROIDERED WASHED PULL-UP PANT TEARDROP TOP EARRINGS Super comfy soft viscose pull-up pants have detailed floral C #8686 BLUE Stars & Stripes Barn $49 Silver teardrop with dangling embroidery in purple shades on the lower left leg. -

The Democratic Party and the Transformation of American Conservatism, 1847-1860

PRESERVING THE WHITE MAN’S REPUBLIC: THE DEMOCRATIC PARTY AND THE TRANSFORMATION OF AMERICAN CONSERVATISM, 1847-1860 Joshua A. Lynn A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History. Chapel Hill 2015 Approved by: Harry L. Watson William L. Barney Laura F. Edwards Joseph T. Glatthaar Michael Lienesch © 2015 Joshua A. Lynn ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Joshua A. Lynn: Preserving the White Man’s Republic: The Democratic Party and the Transformation of American Conservatism, 1847-1860 (Under the direction of Harry L. Watson) In the late 1840s and 1850s, the American Democratic party redefined itself as “conservative.” Yet Democrats’ preexisting dedication to majoritarian democracy, liberal individualism, and white supremacy had not changed. Democrats believed that “fanatical” reformers, who opposed slavery and advanced the rights of African Americans and women, imperiled the white man’s republic they had crafted in the early 1800s. There were no more abstract notions of freedom to boundlessly unfold; there was only the existing liberty of white men to conserve. Democrats therefore recast democracy, previously a progressive means to expand rights, as a way for local majorities to police racial and gender boundaries. In the process, they reinvigorated American conservatism by placing it on a foundation of majoritarian democracy. Empowering white men to democratically govern all other Americans, Democrats contended, would preserve their prerogatives. With the policy of “popular sovereignty,” for instance, Democrats left slavery’s expansion to territorial settlers’ democratic decision-making. -

When Visitors to the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art Read A

1 “For Paintings of Fine Quality” The Origins of the Sumner Fund at the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art On August 16, 1927, Frank B. Gay, Director of the Wadsworth Atheneum, wrote to Edward W. Forbes, Director of the Fogg Art Museum at Harvard, that by the death last week of Mrs. Frank Sumner the Frank Sumner estate now comes to us. I learn from the Trust Company, his trustees and executor that the amount will be upwards of $2,000,000 ‘the income to be used in buying choice paintings.’ Of course we are quite excited here over the prospect for our future.1 The actual amount of the gift was closer to $1.1 million, making the Sumner bequest quite possibly the largest paintings purchase fund ever given to an American museum. Yet few know the curious details of its origins. Today, when visitors to the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art read a label alongside a work of art, they will often see “The Ella Gallup Sumner and Mary Catlin Sumner Collection Fund.” These visitors may well visualize two women—perhaps sisters, perhaps mother and daughter—strolling arm in arm through the galleries of the museum in times past, admiring the art and wondering what they might do for the benefit of such a worthy institution. They would be incorrect. The two women were, in fact, sisters-in-law who died fifty-two years apart and never knew each other. Since 1927 the Sumner Fund has provided the Atheneum with the means to acquire an extraordinary number of “choice paintings.” As of July 2012, approximately 1,300 works of art have been purchased using this fund that binds the names of Ella Gallup Sumner and Mary Catlin Sumner together forever. -

Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum Washington University in St. Louis Sam Fox School of Design & Visual Arts

Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum Washington University in St. Louis Sam Fox School of Design & Visual Arts Spotlight Essay: Thomas Cole, Aqueduct near Rome, 1832 February 2016 William L. Coleman Postdoctoral Fellow in American Art, Washington University in St. Louis When the Anglo-American landscape painter Thomas Cole made his first visit to Italy in the summer of 1831, he embarked on intensive study not only of paintings and sculptures, as so many visiting artists had before him, but also of ancient and modern Italian architecture. In so doing he launched a new phase of his career in which he entered into dialogue with a transatlantic lineage of “painter-architects” that includes Michelangelo, Raphael, and Rubens— artists whose ambitions were not confined to canvas and who were involved extensively with the design and construction of villas and churches, among other projects. Cole was similarly engaged with building projects in the latter decades of his short career, but a substantial body of surviving writings, drawings, and, indeed, buildings testifying to this fact has been largely overlooked by scholars, Thomas Cole, Aqueduct near Rome, 1832. Oil on canvas, 44 1/2 x 67 5/16". Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum, Washington University in St. Louis. presumably because it does not fit neatly with University purchase, Bixby Fund, by exchange, 1987. the myth of Cole as “the father of the Hudson River School” of American landscape painting.1 For an artist whose chief contribution, we have been told, is the argument his work offers for landscape painting as an art of the intellect rather than of mere mechanical transcription of outward appearances, his abiding commitment to the science of building and his professional aspirations in that direction are hard to explain. -

Chief Executive Officer's Report

FISCAL YEAR 2018–19 THIRD QUARTER (JAN–MAR 2019) Chief Executive Officer’s Report June 2019 PAGE NO. Overview 2 Finance 3 Grant Management 5 Public Services 6 The American Place 12 Hartford History Center 14 Communications 17 Development 19 Statistics 20 Staff Updates 25 1 OCTOBEROCTOBER - DECEMBER- DECEMBER 2018 2018 atat a glancea glance JANUARY–MARCH 2019 at a glance 202,659202,659215,512 2,3468042,346 totaltotalTOTAL visits VISITS visits teenTEENteen programPROGRAM program participantsPARTICPANTSparticipants 72,01272,01277,491 189179189 totaltotalTOTAL circulation CIRCULATION circulation citizenshipCITIZENSHIPcitizenship screeningsSCREENINGSscreenings 16,80716,80711,380 2,4962,496 YOUTH PROGRAM 972 youthyouth program program artwalkartwalk visits visits PARTICIPANTS ARTWALK VISITS participantsparticipants 7,7257,72567 2,9011,1812,901 immigrationINDIVIDUALS ACHIEVED intergenerational immigration intergenerationalINTERGENERATIONAL legalCITIZENSHIP consultations legal consultations programsprograms PROGRAMS 2 2 2 finance Fiscal Year 2019—Operating Budget Summary As of March 31, 2018—75% through Fiscal Year For the period ending 3/31/19, Hartford Public Library has expended an estimated total of $6,665,250 which represents 70% of the revised operating budget of $9,526,574. The Library has also collected an estimated $7,749,886 in operating funds, or 81.4% of the Fiscal Year 2019 budget. Budget Actual/Committed Variance % Revenue & Expenditure Revenue $9,562,574 $7,749,886 $1,776,688 81.4% Expense $9,526,574 $6,665,250 $2,861,324 70.0% -

From Carved to Paint

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margin*^ and improper alignment can adversely afreet reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6” x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor. Ml 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. FROM CARVED TO PAINTED: CHESTS OF CENTRAL AND COASTAL CONNECTICUT, c. -

Coltsville National Park Visitor Experience Study

Coltsville National Park Visitor Experience Study museumINSIGHTS in association with objectIDEA Roberts Consulting Economic Stewardship November 2008 Coltsville National Park Visitor Experience Study! The proposed Coltsville National Park will help reassert Coltsville’s identity as one of Hartford’s most important historic neighborhoods. That clear and vibrant identity will help create a compelling destination for visitors and a more vibrant community for the people of Hartford and Connecticut. Developed for the Connecticut Trust for Historic Preservation by: museumINSIGHTS In association with Roberts Consulting objectIdea Economic Stewardship November 2008 The Connecticut Trust for Historic Preservation received support for this historic preservation project from the Commission on Culture & Tourism with funds from the Community Investment Act of the State of Connecticut. Contents Executive Summary ....................................................................! 1 A. Introduction ..............................................................................! 4 • Background • History of Colt and Coltsville • Goals of the Coltsville Ad Hoc Committee • Opportunities and Challenges • Coltsville Ad Hoc Committee Partners B. The Place, People, and Partners ..................................! 8 • The Place: Coltsville Resources • The People: Potential Audiences • The Partners in the Coltsville Project C. Planning Scenarios ............................................................! 14 • Overview • Audiences & Potential Visitation • Scenario