CA ANZ's Submission to the Tax Working Group

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Effectiveness of Tax Reviews in New Zealand: an Evaluation and Proposal for Improvement

THE EFFECTIVENESS OF TAX REVIEWS IN NEW ZEALAND: AN EVALUATION AND PROPOSAL FOR IMPROVEMENT The Centre for Commercial and Corporate Law Inc 2020 i The Effectiveness of Tax Reviews in New Zealand: An Evaluation and Proposal for Improvement Published in Christchurch by The Centre for Commercial & Corporate Law Inc School of Law, University of Canterbury Private Bag 4800, Christchurch, New Zealand ISBN 978-0-473-52769-3 This publication is copyright. Other than for the purposes of and on the conditions prescribed by the Copyright Act no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means whether electronic, mechanical, microcopying, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior written permission of the copyright owner(s). The publisher, authors and editors expressly disclaim any and all liability to any person whether a purchaser of this publication or not in respect of anything or the consequences of anything done or omitted in reliance in whole or part. Published by the University of Canterbury ii Foreword FOREWORD This book proposes the establishment of a New Zealand Taxation Review Commission (NZTRC). It develops its argument for this in two ways. First, there is a survey of ad hoc tax reviews between 1922 and 2019. This survey ends with an analysis of the learnings that can be drawn from these reviews and draws together some thoughts on the characteristics of ‘best practice’ for review committees. Secondly, lessons are sought from a selection of permanent bodies that consider aspects of tax policy in a number of other countries. -

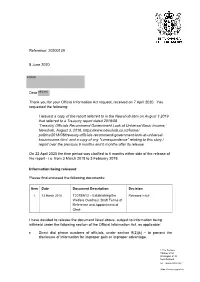

Official Information Act Response 20200139

Reference: 20200139 8 June 2020 s9(2)(a) Dear s9(2)(a) Thank you for your Official Information Act request, received on 7 April 2020. You requested the following: I request a copy of the report referred to in the Newshub item on August 3 2019 that referred to a Treasury report dated 2018/08 ‘Treasury Officials Recommend Government Look at Universal Basic Income,’ Newshub, August 3, 2018, https://www.newshub.co.nz/home/ politics/2018/08/treasury-officials-recommend-government-look-at-universal- basicincome.html. and a copy of any "correspondence" relating to this story / report over the previous 6 months and 6 months after its release. On 22 April 2020 the time period was clarified to 6 months either side of the release of the report - i.e. from 3 March 2018 to 3 February 2019. Information being released Please find enclosed the following documents: Item Date Document Description Decision 1. 13 March 2018 T2018/613 – Establishing the Released in full Welfare Overhaul: Draft Terms of Reference and Appointment of Chair. I have decided to release the document listed above, subject to information being withheld under the following section of the Official Information Act, as applicable: Direct dial phone numbers of officials, under section 9(2)(k) – to prevent the disclosure of information for improper gain or improper advantage. 1 The Terrace PO Box 3724 Wellington 6140 New Zealand tel. +64-4-472-2733 https://treasury.govt.nz Direct dial phone numbers of officials have been redacted under section 9(2)(k) in order to reduce the possibility of staff being exposed to phishing and other scams. -

Public Submissions: Michael Littlewood

Tax Working Group Public Submissions Information Release Release Document September 2018 taxworkingroup.govt.nz/key-documents Key to sections of the Official Information Act 1982 under which information has been withheld. Certain information in this document has been withheld under one or more of the following sections of the Official Information Act, as applicable: [1] 9(2)(a) - to protect the privacy of natural persons, including deceased people; [2] 9(2)(k) - to prevent the disclosure of official information for improper gain or improper advantage. Where information has been withheld, a numbered reference to the applicable section of the Official Information Act has been made, as listed above. For example, a [1] appearing where information has been withheld in a release document refers to section 9(2)(a). In preparing this Information Release, the Treasury has considered the public interest considerations in section 9(1) of the Official Information Act. SUBMISSIONS TO THE TAX WORKING GROUP 2018 MICHAEL LITTLEWOOD Contact details Professor Michael Littlewood University of Auckland Law School [1] 30 April 2018 INTRODUCTION 1. I am a Professor of Law at the University of Auckland Law School. My principal field of expertise is tax law and tax policy. I have published extensively in these areas both in New Zealand and in other countries. I am a fulltime academic but I have also from time to time provided advice to individuals, business interests and the governments of several countries. I make these submissions in my personal capacity. 2. On 14 March 2018 the Tax Working Group recently established by the government published a paper called Future of Tax: Submissions Background Paper. -

A Tax System for New Zealand's Future

A Tax System for New Zealand’s Future Report of the Victoria University of Wellington Tax Working Group January 2010 A Tax System for New Zealand’s Future Report of the Victoria University of Wellington Tax Working Group January 2010 Centre for Accounting, Governance and Taxation Research, Victoria University of Wellington, Wellington, New Zealand ISBN 978-0-478-35006-7 (Print) 978-0-478-35007-4 (Online) PAGE 1 Contents Foreword 5 Summary 9 Chapter 1: A World-Class Tax System: the Approach of the Tax Working Group 13 1.1 The need for change 13 1.2 The role of taxes 13 1.3 Problems with the current system 16 1.4 A future tax system for New Zealand 19 Chapter 2: Concerns with the Current Tax System 21 2.1 Problems with the structure of the New Zealand tax system 21 2.2 A lack of coherence, integrity and fairness 28 2.3 The sustainability of the current tax system 33 Chapter 3: Options for Change to the New Zealand Tax System 37 3.1 Alignment of top personal, corporate, PIE and trust rates, with imputation 38 3.2 Non-alignment of personal, corporate, PIE and trust rates 39 3.3 Ways to broaden the tax base and fund tax reform 44 3.4 Changes to the system of social welfare transfers 55 3.5 Institutional reform 57 Chapter 4: Conclusions and a Way Forward 59 4.1 The status quo is not a viable option 59 4.2 There are choices around taxation reform 60 4.3 A way forward 64 Tax Working Group Background Papers 68 Endnotes 70 PAGE 3 Foreword The Tax Working Group (TWG) was established by Victoria University of Wellington’s Centre for Accounting Governance and Taxation Research, in conjunction with the Treasury and Inland Revenue, in May 2009. -

New Zealand Report Oliver Hellmann, Jennifer Curtin, Aurel Croissant (Coordinator)

New Zealand Report Oliver Hellmann, Jennifer Curtin, Aurel Croissant (Coordinator) Sustainable Governance Indicators 2020 © vege - stock.adobe.com Sustainable Governance SGI Indicators SGI 2020 | 2 New Zealand Report Executive Summary New Zealand’s year was overshadowed by the right-wing terrorist attack on a mosque in Christchurch in March of 2019, which killed 51 people. However, it would be wrong to interpret this horrific incident as a failure of governance failure. Instead, the decisive and swift political response in the aftermath of the attack demonstrates that New Zealand’s political system is equipped with high levels of institutional capacity. Within weeks of the politically motivated mass shooting, the government passed tighter guns laws, rolled out a gun buy-back scheme, and established a specialist unit tasked with investigating extremist online content. Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern was also widely praised for her sensitivity and compassion in the wake of the Christchurch massacre. Generally speaking, policymaking is facilitated by New Zealand’s Westminster-style democracy, which concentrates political power in the executive and features very few veto players. Even though the mixed-member electoral system – which replaced the old first-past-the-post system in 1996 – produces a moderately polarized party system and typically fails to deliver absolute parliamentary majorities, this does not impede cross-party agreements in policymaking. However, while New Zealand’s political system is commonly regarded as one of the highest-quality democracies in the world, the country struggles with issues of media pluralism. The media market is dominated by (mostly foreign-owned) commercial conglomerates, which place greater emphasis on entertainment than on critical news-gathering. -

Greenpeace New Zealand 30 April 2018

Greenpeace New Zealand 30 April 2018 Hon Sir Michael Cullen Tax Working Group Secretariat PO Box 3724 Wellington 6140 New Zealand Greenpeace submission to the New Zealand Government’s Tax Working Group on the Future of Tax Summary: New Zealand’s water quality, soil health, and biodiversity are in decline, and emissions of dangerous greenhouse gases are increasing. We have a moral obligation to future generations to curb this degradation and restore our natural environment. Perverse environmental outcomes have often resulted from market failures. These failures unjustly place the cost of environmental degradation onto society, rather than those responsible. Greenpeace supports the Government using taxation as a way to correct for these failures for the benefit of the environment and the New Zealand public. The OECD acknowledges that many environmental taxes implemented by its member countries are poorly designed and targeted. Too often, big polluters are exempt from an environmental tax due to unjustified competitiveness claims, compromising its environmental effectiveness and leaving the wider public to cover the cost. Greenpeace urges the Government to stand up to lobbyists and polluters and implement environmental taxes with as few exemptions as possible, and at rates which drive behaviour change. Greenpeace advocates that the revenues from new environmental taxes be used to provide an income tax free threshold. Submission: Dear Hon Sir Michael Cullen, Greenpeace New Zealand, Inc. (Greenpeace) thanks you for the invitation to provide our views on ways to improve the fairness, balance and structure of the tax system in New Zealand over the next 10 years. The following submission will focus on environmental taxes. -

New Zealand's 'Experience' with Capital Gains Taxation and Policy

eJournal of Tax Research (2019) vol. 16, no. 2, pp. 362-392 New Zealand’s ‘experience’ with capital gains taxation and policy choice lessons from Australia Kerrie Sadiq and Adrian Sawyer Abstract New Zealand taxes a number of types of capital gains as ordinary income at the standard income tax rates but it is an outlier within OECD countries for not having a separate comprehensive capital gains tax (CGT). Over the years, numerous proposals for a CGT have been made by political opposition parties as part of their policy platform; none of these parties have been successful in forming part of a government and, as such, their proposals have failed to come to fruition. The Tax Working Group in 2009 came very close to recommending a CGT for New Zealand as part of a portfolio of tax policy options. The bright-line test for the purchase and sale of residential property within two years of acquisition was introduced in 2015. The debate nevertheless continues over whether New Zealand should embrace a formal standalone CGT. This article reviews previous attempts at introducing a CGT into New Zealand, traverses the ongoing debate, and outlines some of the key policy choices that need to be carefully examined should a future government announce that it is working on a CGT. The analysis is undertaken within a comprehensive tax base framework which applies income tax to net economic gain, adjusted for inflation. The article then considers modifications to this ‘ideal’ framework based on the design principles of equity, efficiency, simplicity, sustainability and policy consistency. Given Australia has had a CGT regime in place since 1985, with the regime going through several amendments in the intervening years, much of this analysis is drawn from that experience. -

Tax Working Group

December 2018 | Volume 11, Issue 4 of the quarterly RPRC Update. Tax Working Group: A wasted Contents opportunity for change? Page 2 FSC Conference: Susan St Susan St John and Michael Littlewood made Submissions in John on Decumulation; response to the Tax Working Group (TWG) Interim Report. Summaries of those Submissions are below. The full submission from RPRC Submission on the St John is here, and the submission from Littlewood is here. Electricity Price Review. The TWG’s Interim Report is available here. The Foreword to that report begins: Page 3 Taxation is a matter which can arouse strong passions, deep Feedback on the disagreements, and much confusion. That is, in part, due to ‘strawman’ proposal for two things. The first is that while many people do not like Irish pension reform; paying tax, few want to do away with the services tax pays for: supporting the retired, health, education, infrastructure In NewsRoom, Some (including public transport), the protection of the myths about NZ Super. environment, public order and much more. The second, which helps explain the breadth and complexity of this interim Page 4 report, is that arguably no forms of tax are all bad, neither Grey Power’s petition are they all good. Taxes live in the world of greys, not that of black and white …. against Spousal Provision; KiwiSaver financial The TWG’s Interim Report made three recommendations on the tax hardship withdrawals treatment of retirement savings: - Remove ‘employer superannuation contribution tax’ on the 3% jump 60% in 2 years; mandatory contributions by employers to KiwiSaver for employees’ earning up to $48,000 a year. -

A History of Taxing Capital Gains in New Zealand: Why Don't We?

Auckland University Law Review Vol 20 (2014) A History of Taxing Capital Gains in New Zealand: Why Don't We? MELINDA JACOMB* This article considers how New Zealand has treated and taxed or, rather, not taxed capital gains. It attempts to cast light on why there is no comprehensive capital gains tax regime in New Zealand when this tax treatment is an orthodox part of almost all other OECD countries' tax systems. This article begins by placing New Zealand's approach to taxing capitalgains in an internationalcontext, setting out the main argumentsfor a capitalgains tax. Then, startingwith PremierJohn Ballance 's Land and Income Tax Assessment Act of 1891, the article surveys the introduction of income taxation in New Zealand The 1891 Act introduced the income tax that we know today. However, due to the distinction drawn between capitaland revenue by a long history of case law and a redraft of the Act in 1900, our modern day "income tax" does not capture income from capital gains. The article then traces four key attempts in more recent political history to capture capital gains through the introduction of a form of capital gains tax. The article concludes with a summary of the core existing provisions in the Income Tax Act 2007 that function to capture some types of capitalgains and a reflection on what the taxfuture may holdfor capitalgains in New Zealand I INTRODUCTION Once upon a time there was a country, far, far away, at the bottom of the globe. It was a scenic land with sparkling lakes, snow-capped mountains, rolling green farmlands and majestic fiords. -

Social Law Reports Towards Wellbeing? Developments in Social Legislation and Policy in New Zealand

MAX PLANCK INSTITUTE FOR SOCIAL LAW AND SOCIAL POLICY Social Law Reports Michael Fletcher Towards Wellbeing? Developments in Social Legislation and Policy in New Zealand Reported Period: 2018 No. 2/2019 New Zealand – Report 2018 Cite as: Social Law Reports No. 2/2019 © Max Planck Institute for Social Law and Social Policy, Munich 2019. Department of Foreign and International Social Law All rights reserved. ISSN 2366-7893 Max Planck Institute for Social Law and Social Policy Amalienstrasse 33, D-80799 Munich, Germany Tel.: +49 (0)89 38602-0 Fax: +49 (0)89 38602-490 E-mail: [email protected] http://www.mpisoc.mpg.de New Zealand – Report 2018 CONTENT OVERVIEW 1. INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................... 1 2. CURRENT POLITICAL, ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL SITUATION ................................................... 2 2.1. THE POLITICAL SITUATION .................................................................................................................. 2 2.2. ECONOMIC AND FISCAL CONDITIONS.................................................................................................... 2 2.3. SOCIAL CONDITIONS .......................................................................................................................... 4 3. CASE LAW DEVELOPMENTS .................................................................................................... 5 4. SOCIAL POLICY AND SOCIAL LAW DEVELOPMENTS DURING 2018 ....................................... -

MOOD of the BOARDROOM Mood of the Boardroom 2019 What’S Inside the Herald’S Mood of the Boardroom 2019 Ceos Survey Attracted Participation from 157 Respondents

Tuesday,September 24,2019 Moodofthe BOARDROOMnzherald.co.nz/business Walking a tightrope 150+ CEOs sharetheir views INSIDE •FranO’Sullivan•Thomas Pippos •GillSouth •LiamDann •Tim McCready •DuncanBridgeman D2 nzherald.co.nz | The New Zealand Herald | Tuesday, September 24, 2019 MOOD OF THE BOARDROOM Mood of the Boardroom 2019 What’s inside The Herald’s Mood of the Boardroom 2019 CEOs Survey attracted participation from 157 respondents. This year there were some 140 chief executives including CEOs of some of NZ’s biggest companies, some publicly owned institutions and heads of several influential business organisations and several directors. The Herald survey is conducted in association with BusinessNZ. BusinessNZ put 15 questions from the survey to its membership attracting afurther 150 responses from business heads. The survey is now in its 18th year having been launched in December 2002 within a NZ Herald State of the Nation report. Watch the debate Finance Minister Grant Robertson Home and away The confidence National’s fast Executives’ pick and National’s Finance —D4 trick —D6-9 learner —D13 for mayor —D14 Spokesperson Paul Goldsmith will debate the survey results at a breakfast at the Cordis Hotel in Auckland this morning. The debate will be chaired by NZME managing editor Shayne Currie. nzherald.co.nz will feature video from the debate and interviews with leading CEOs attending the breakfast. MOOD OF THE BOARDROOM Executive Editor: Fran O’Sullivan Writers: Bill Bennett, Duncan Bridgeman, Liam Dann, Tim McCready, Thomas Pippos and -

Official Information Act Response 20190529

Reference: 20190529 3 September 2019 s9(2)(a) Dear s9(2)(a) Thank you for your Official Information Act request, received on 8 August 2019. You requested the following: A list of all requests under the Act that have been responded to by the Treasury in the period 1 April 2019 to 30 June 2019. Please provide a brief description of the request, the date the request was received and the date the request was responded to. I do not require the name of the requestor, however where a political office or organisation has made the request, please provide this. Information being released Please find enclosed the following documents: Item Date Document Description Decision 1. N/A List of OIAs responded to Release in full between 1 April 2019 and 30 June 2019 Please note that this letter (with your personal details removed) and enclosed documents may be published on the Treasury website. This reply addresses the information you requested. You have the right to ask the Ombudsman to investigate and review my decision. Yours sincerely David Hammond Team Leader Ministerial Advisory 1 The Terrace PO Box 3724 Wellington 6140 New Zealand tel. +64-4-472-2733 https://treasury.govt.nz IN-CONFIDENCE List of OIAs responded to between 1 April 2019 and 30 June 2019 Submitter Response Date Received Title Organisation Date 4/02/2019 EQC Inquiry Draft Terms of Reference 4/04/2019 18/02/2019 Demographic breakdown and total numbers of 12/04/2019 employees 24/02/2019 Tax Working Group - Total Cost 18/04/2019 25/02/2019 Information relating to Provincial Growth Fund