Irvine Valley College Project Instructor Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fullerton College

Fullerton College Rolando (Rolo) Sanabria, Ed.D. Educational Partnerships and Outreach, Faculty Coordinator CA COMMUNITY COLLEGES CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY 115 CCC 23 Universities Enter from High School Transfer from CCC AA/AS, Certificate, Transfer Readiness BA, MA, Professional UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Higher OR 10 Universities Transfer from CCC Education BA, MA, PhD, Professional in California PRIVATE OR UNIVERSITIES 76 Accredited Transfer from CCC High School Freshman 1 year Sophomore 1 year Junior 1 year Senior 1 year Community 4-year College Universities Freshman Sophomore Junior Senior Fullerton College Transfer Students Fall 2018 Transfer Students Fullerton CSUF College Enrolled 662 3,613 Avg. Transfer GPA 3.20 3.32 Full‐Time Unit Load 78.1% 77.2% Avg. Units 11.78 11.84 Avg. Age 21.5 26.0 Women 55.4% 57.8% Student is First Generation 33.4% 31.4% 7 FALL 2018 TRANSFERS MATRICULATED TOP 20 COMMUNITY COLLEGES # of # of Institution of Origin Institution of Origin Transfers Transfers Fullerton College 662 Cerritos Community College 48 Orange Coast College 369 Chaffey Community College 47 Saddleback College 360 Rio Hondo Community College 44 Santa Ana College 309 Riverside Community College 43 Irvine Valley College 284 Coastline Community College 36 Cypress College 249 Pasadena Community College 34 Santiago Canyon College 240 Norco College 29 Golden West College 175 Long Beach City College 26 Mount San Antonio College 101 El Camino College 23 Citrus Community College 58 Mount San Jacinto College 23 8 What are the Benefits? Access → -

Outreach Engagement

PRESIDENT'S REPORT BOARD OF TRUSTEES MEETING Tuesday, May 15, 2018 Outreach Iron-workers Apprenticeship Training As part of the Strong Workforce pre-apprenticeship grant in partnership with Ironworkers, Local 229, Grossmont College’s Career Technical Education and Workforce Development division will host an iron-workers pre-apprenticeship training information session from 1 – 3 p.m., Monday, May 14, and 1 – 3 p.m., Monday, May 21. At the information sessions held in the Grossmont College Career Center in Bldg. 60, room 140, attendees will learn how to qualify in the free pre-apprenticeship program and career opportunities with Ironworkers Local 229. To RSVP, please visit tinyurl.com/ironworkersinfosession. Outreach In late April, more than 50 8th graders from Chet F. Harritt STEAM School in Santee visited Grossmont College as part of college and career exploration for the science, technology, engineering, arts and math-focused (STEAM) school. Led by campus ambassadors, the students visited the Hyde Art Gallery, the Patient Simulation Lab in Allied Health and Nursing, and the Culinary Arts dining room and kitchen. Following the tour, they participated in hands-on experiments with the Science Club before departing for the day. Science Fair & STEM Event In April, faculty from Physics, Astronomy and Physical Science; Earth Sciences and Chemistry departments, visited Fletcher Hills Elementary to present on various science topics during their Science Fair & STEM event. The Science Club held a variety of demonstrations, while Physics, Astronomy and Physical Science hosted their planetarium. This is the third year the departments have participated. Family Orientation Grossmont College held a Family Orientation on Monday, May 14. -

Dr. John Hernandez Accepts Position of Irvine Valley College President

CONTACT: Letitia Clark, MPP - 949.582.4920 - [email protected] FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: May 28, 2020 Dr. John Hernandez Accepts Position of Irvine Valley College President MISSION VIEJO, CA— A nationwide search, candidate interviews, and public forums were held via Zoom in the selection process to identify the next Irvine Valley College President. After a several month process, a decision has been made, and Chancellor Kathleen Burke has announced that she is recommending that Dr. John Hernandez serve in the role as Irvine Valley College’s new president. Dr. Hernandez has been an educator for over 30 years – 22 of those years in administration. He was appointed President of Santiago Canyon College (Orange, CA) in July 2017 and served as Interim President there from July 2016 until his permanent appointment. Prior to that, he was the college’s Vice President for Student Services (2005 to July 2016). Before joining Santiago Canyon College, Dr. Hernandez was Associate Vice President and Dean of Students at Cal Poly Pomona; Associate Dean for Student Development at Santa Ana College and Assistant Dean for Student Affairs at California State University, Fullerton. Additionally, Dr. Hernandez has been an adjunct instructor in the Student Development in the Higher Education graduate program at California State University, Long Beach and taught counseling and student development courses at various colleges as well. Dr. Hernandez will immediately begin the transition process from his role as President of Santiago Canyon College within the Rancho Santiago Community College District. He is expected to start at Irvine Valley College on August 1, 2020, pending ratification of his contract by the South Orange County Community College District (SOCCCD) Board of Trustees. -

The State of Veteran Students in California Community Colleges: 2018 Statewide Study RP Group | March 2019 | Page Table of Contents Acknowledgements 2

The State of Veteran Students in California Community Colleges 2018 STATEWIDE STUDY Nancy L. Montgomery, RN, MSN — Lead Daniel Avegalio, MS Eric Garcia, EdD Mia Grajeda, MSW Ezekiel Hall, BA Patricia D’Orange-Martin, MS Glen Pena, MSW Todd Steffan, MS March 2019 www.ivc.edu Acknowledgements The Research and Planning Group for California Community Colleges (RP Group) would like to express its gratitude to Nancy Montgomery, Assistant Dean of Health, Wellness, and Veterans Services at Irvine Valley College, whose dedication to the academic success of both the California Community College Veteran student population and the centers that support these students was the impetus for this project. We would also like to recognize the participation by the California Community Colleges (CCC) who provided their time and resources, in terms of staff and students, in order for us to obtain the data and information needed to conduct this study. Lastly, we would like to thank the Veteran students themselves for sharing their experiences so openly with us. The Research Team from RP Group who analyzed the data and wrote the report include the following dedicated members: Project Team Tim Nguyen Ireri Valenzuela Andrew Kretz Alyssa Nguyen Editors Darla Cooper Priyadarshini Chaplot www.rpgroup.org 2 The State of Veteran Students in California Community Colleges: 2018 Statewide Study RP Group | March 2019 | Page Table of Contents Acknowledgements 2 Table of Contents 3 Executive Summary 6 Background 6 Findings and Recommendations 6 Concluding Remarks 9 Introduction -

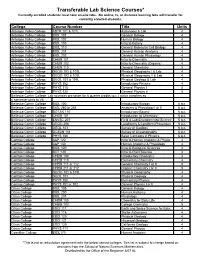

Transferable Lab Science Courses* Currently Enrolled Students Must Take On-Site Labs

Transferable Lab Science Courses* Currently enrolled students must take on-site labs. No online, tv, or distance learning labs will transfer for currently enrolled students. College Course Number Title Units Antelope Valley College ASTR 101 & 101L Astronomy & Lab 4 Antelope Valley College BIOL 101 General Biology 4 Antelope Valley College BIOL 102 Human Biology 4 Antelope Valley College BIOL 103 Intro to Botany 4 Antelope Valley College BIOL 110 General Molecular Cell Biology 4 Antelope Valley College BIOL 201 General Human Anatomy 4 Antelope Valley College BIOL 202 General Human Physiology 4 Antelope Valley College CHEM 101 Intro to Chemistry 5 Antelope Valley College CHEM 102 Intro to Chemistry (Organis) 4 Antelope Valley College CHEM 110 General Chemistry 5 Antelope Valley College GEOG 101 & 101L Physical Geography I & Lab 4 Antelope Valley College GEOG 102 & 102L Physical Geography II & Lab 4 Antelope Valley College GEOL 101 & 101L Physical Geology & Lab 4 Antelope Valley College PHYS 102 Introductory Physics 4 Antelope Valley College PHYS 110 General Physics I 5 Antelope Valley College PHYS 120 General Physics II 5 Bellevue Comm College: Lab sciences are taken for 6 quarter credits (q.c.) which transfers as 4 semester units to VU Bellevue Comm College BIOL 100 Introductory Biology 6 q.c. Bellevue Comm College BIOL 260 or 261 Anatomy & Physiology I or II 6 q.c. Bellevue Comm College BOTAN 110 Introductory Botany 6 q.c. Bellevue Comm College CHEM 101 Introduction to Chemistry 6 q.c. Bellevue Comm College ENVSC 207 Field & Lab Environmental Science 6 q.c. Bellevue Comm College GEOG 206 Landforms & Landform Processes 6 q.c. -

2020-21 Five Year Capital Outlay Plan

2019 REPORT 2020-21 Five Year Capital Outlay Plan California Community Colleges Chancellor’s Office | Eloy Ortiz Oakley, Chancellor ELOY ORTIZ OAKLEY Chancellor Aug. 21, 2019 The Honorable Gavin Newsom Governor of California State Capitol Sacramento, CA 95814 RE: Report on California Community Colleges Five-Year Capital Outlay Plan for 2020-21 Dear Gov. Newsom: The California Community Colleges Chancellor’s Office and the Board of Governors are pleased to release the 2020-21 Five-Year Capital Outlay Plan for the California Community Colleges. The California Community Colleges has more than 2.1 million students enrolled in its 73 districts, 115 college campuses and 78 approved educational centers. The infrastructure used to facilitate its educational programs and administrative operations includes more than 25,000 acres of land, 5,956 buildings and 87 million gross square feet of space that includes 54 million assignable square feet of space. To support community college districts grow and improve their educational facilities, the Facilities Planning Unit of the California Community Colleges Chancellor’s Office annually reviews and approves local Five-Year Capital Outlay Plans as part of the Capital Outlay grant application process. The Facilities Planning Unit also works alongside the Board of Governors of the California Community Colleges to develop an annual systemwide Five- Year Capital Outlay Plan pursuant to California Regulation and Education Code. The Five- Year Capital Outlay Plan is presented to California Legislature in conjunction with the Governor’s Budget, and it clarifies statewide needs and priorities of the California Community Colleges. We believe that proper educational facilities play a vital role in supporting the goals and commitments outlined in the California Community Colleges Vision for Success (Vision for Success). -

Apply for a $500 SCHEC Need Help with Expenses After You Transfer?

Need help with expenses after you The South Coast Higher Education Council (SCHEC) is pleased to be offering several $500 scholarships for the 2017-2018 academic year. Transfer? Those who meet the following criteria are invited to . apply for a SCHEC Scholarship: Currently enrolled in a SCHEC institution and will be transferring as a full-time student to a SCHEC four-year college/university* Apply during the 2017-2018 academic year for a Have a 3.0 or higher cumulative GPA Applications must be postmarked no later than $500 March 10, 2017! SCHEC Application materials can be found at: http://www.schec.net Questions? Contact: Scholarship Melissa Sinclair at CSU Fullerton: [email protected] Carmen Di Padova at Alliant International University: [email protected] Alliant International University CSU Long Beach Rio Hondo College The following colleges, Argosy University Cypress College Saddleback College universities and Azusa Pacific University DeVry University Santa Ana College Biola University El Camino College Santiago Canyon College professional schools Brandman University Fullerton College Southern California University are members of the Cerritos College Golden West College Trident University International South Coast Higher Chapman University Hope International University Trinity Law School Citrus College Irvine Valley College UC, Irvine Education Council Coastline College Loma Linda University UC, Riverside (SCHEC): Concordia University Long Beach City College University of La Verne Columbia University Mt. San Antonio College University of Redlands CSPU, Pomona National University Vanguard University CSU, Dominguez Hills Orange Coast College Webster University CSU, Fullerton Pepperdine University—Irvine Whittier College . -

Degree Mapping Cover Sheet the Next Phase of Realizing the Potential and Promise of Academic and Career Pathways Involves Asking Departments to Create Degree Maps

Degree Mapping Cover Sheet The next phase of realizing the potential and promise of Academic and Career Pathways involves asking departments to create Degree Maps. What is a Degree Map (and how is it different from the program map developed years ago)? Degree maps represent a clear, coherent, and structured educational experience that culminates in a degree, certificate, or successful transfer to a university. Whereas Program Maps included the program of study (courses required by the degree), Degree maps include: The intended program of study, Recommended GE courses, Recommended electives Why Degree Maps? They provide students with a clear picture of how to complete a degree saving students time and money. They provide students with a roadmap, particularly in the time before students see a counselor to produce a formal Ed Plan (which often does not occur until the 2nd or 3rd semester). They are an equity consideration. Once a student sees a counselor, they provide the counselor with a clearer picture of the student’s educational goals Sample AOJ Degree Map from Irvine Valley College in order to make modifications needed for transfer. Degree Mapping Principles: Degree maps provide clarity for ALL (students, faculty, staff, counselors, college leadership, and external stakeholders). Degree Maps provide a recommended path to complete a program in four semesters (for an AA degree) or less (for certificate programs that are less than a year in duration) Degree maps are based on the assumptionDRAFT all students have capacity to succeed Degree Map Elements At least one program course in first semester Three program courses in first year Appropriate math pathways that align with student end goals Completion of transfer-level math and transfer-level English in the first academic year Academic and student support milestones * In the future, degree maps may also include co-curricular activities and learning experiences that complement program of study (i.e. -

Irvine Valley College's Veterans Resource Center Operations

Irvine Valley College’s Veterans Resource Center Operations and Spending Survey Results 2019-2020 Katie Brohawn, PhD Andrew Kretz, PhD Alyssa Nguyen, MA Michelle White, MA March 2020 www.rpgroup.org Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................ 3 Introduction ........................................................................................................................... 5 Survey Results ........................................................................................................................ 6 Operations 6 Spending 10 Conclusion and Recommendations ....................................................................................... 17 Appendix A: College Represented by Survey Participants ..................................................... 18 Appendix B: Roles of Survey Participants .............................................................................. 19 Appendix C: VRC Minimum Standards .................................................................................. 20 Appendix D: Managing Role of VRC Budgets ......................................................................... 21 IVC’s Veterans Resource Center Operations and Spending Survey Results 2019-20 RP Group | March 2020 | Page 2 Executive Summary The 2017–18 State Budget Act allocated $5M to the Board of Governors of the California Community Colleges (CCC) to support a Veterans Resource Center (VRC) grant program designed to help -

Summer Advantage Fall 2018 Analysis Summary

Summer Advantage Fall 2018 Analysis The 2018 Summer Advantage Program consisted of four days of workshops covering a variety of topics to help students transition into their first year of college. In 2017 a new placement method was implemented at Norco College. Students received Multiple Measure placements (MMAP) based on their high school performance, so advancement in English and Math was no longer the priority of the program. In all, 1,150 students applied to the program and 712 were invited to attend NOW week. Three hundred and ninety-five students completed the entire program (all four days of NOW week). Summary Applicants 1,150 Eligible (Invited) 712 (61.9%) RSVP ~500 Participated 413 Early Registration 395 (55.5%) Students were divided into groups by their appropriate School. The School breakdown is below. School Students Percent Arts & Humanities 58 14.0% Business and Management 84 20.3% Social & Behavioral Studies 95 23.0% STEM - Science & Health 108 26.2% STEM - Tech, Engineering and Math 68 16.5% Total 413 100% Enrollment in Summer or Fall 2018 An analysis of Summer and Fall 2018 enrollment and success of Summer Advantage students was completed. Three-hundred and sixty-two of the 395 SA students enrolled past census in Summer ot Fall 2018. The overall success rates for all Fall 2018 enrollments were compared. This comparison includes all courses a student enrolled in, not just Math and English. All enrollments of SA participants were compared to all enrollments of first-time students at Norco College. There is a significant difference in course success and retention between groups, with the SA group being higher in both. -

INSIDE... President’S Office

INSIDE... President’s Office ......................1 October 4, 2019 PRESIDENT’S OFFICE Office of Instruction .................2 Student Services ........................4 North San Diego Economic Development Council Board Meeting The College hosted the North San Diego Finance And Administration ...4 Economic Development Council Board Meeting on Wednesday, September 11. I provided an Human Resources .....................5 overview and update of campus initiatives and Research and Planning ..............5 opportunities for partnerships. Director Rungaitis invited members to participate in Palomar Foundation activities and the importance Public Affairs Office ..................6 of serving on the President’s Associates. Foundation ..................................7 ACCCA Mentor 2019 Southern CA Fall Retreat On Friday, September 13, the ACCCA Mentor program held its Southern CA Upcoming Events .......................9 mentor retreat at the Rancho Bernardo Center. Participants included administrators from Southern California. I conducted a workshop on strategies for change leadership. The discussion covered current state initiatives, leadership and emotional agility. Board of Governors Presentation Student Housing On Monday, September 16, I attended the CA Board of Governors (BOG) meeting. I served on a panel to discuss funding for student housing. The discussion was facilitated by Christian Osmena, CCCO Vice Chancellor of Finance and other panelists were Dr. Frank Chong from Santa Rosa Junior College and Dr. Keith Curry from Compton College. There was interest by the BOG to consider funding for feasibility studies. President Blake and fellow panelists Meeting with SDSU President Adela de la Torre On Friday, October 4, we hosted Dr. Adela de la Torre, President of San Diego State University, at the Rancho Bernardo Education Center. Dr. de la Torre and her team were given a tour of the Center. -

4-17 OEC-Constitution-2017-18.Pdf

ORANGE EMPIRE CONFERENCE CONSTITUTION 2017-2018 TABLE OF CONTENTS ARTICLE I ARTICLE IV The Orange Empire Conference ...... 1 Officers – Representatives – 1.01 Name ........................................... 1 Committees - Duties ........................... 5 1.02 Purpose ........................................ 1 4.01 President ...................................... 5 1.03 Goals............................................ 1 4.02 President-Elect ............................. 5 1.04 Gender Equity ............................. 1 4.03 Commissioner’s Office ................ 6 1.05 Objectives .................................... 2 4.04 Commissioner’s Duties, Responsibilities and Term ................... 6 1.06 Membership ................................. 2 4.05 Executive Committee .................. 7 1.07 Criteria for New Membership ..... 2 4.06 Sports Representatives ................. 8 1.08 Compliance ................................. 2 ARTICLE V ARTICLE II Representation - Powers and Duties .. 3 Compliance - Procedure - Penalties . 10 2.01 Conference Representation ........ 3 5.01Compliance ................................... 10 2.02 Powers and Duties ....................... 3 5.02 Procedures ................................... 10 5.03 Penalties ....................................... 11 ARTICLE III 5.04 Hearing Board and Appeals ......... 11 Meetings - Agenda - Quorum - Voting 5.05 Protests ......................................... 12 - Legislation ........................................ 4 3.01 Meetings ....................................