Negotiated Planning': Diverse Trajectories Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

South Africa 12 Nights / 13 Days

SOUTH AFRICA 12 NIGHTS / 13 DAYS 304, SUKH SAGAR BUILDING, 3RD FLOOR, N. S. PATKAR MARG, HUGHES ROAD, CHOWPATTY, MUMBAI – 400 007. TEL: 2369 7578 / 2361 7578 / 2368 2421 / 2367 2160 / 2362 2160 / 2362 2421 / 9920045551 E-MAIL: [email protected] WEBSITE : www.comfort-voyages.com DEPARTURE DATES APRIL: 16, 20, 24, 28 MAY: 02, 04, 06, 08, 10, 12, 14, 16, 18, 20, 22, 24, 26, 28, 30 JUNE: 03, 07, 11, 15, 19, 23 DAY 00: MUMBAI – ADDIS ABABA Arrive at Mumbai International Airport to board flight to Addis Ababa. On arrival into Addis Ababa airport proceed for your connecting flight to Cape Town. DAY 01: ADDIS ABABA – CAPE TOWN Arrive into Cape Town & proceed to clear your customs & immigration. Later board your coach and proceed towards your hotel & check in. Evening free at Leisure. Dinner and Overnight in Cape Town. DAY 02 : CAPE TOWN After breakfast proceed to the cable car station, for a cable car ride up Table Mountain (if weather permits), It gives breath-taking views over the city and its beaches. Later we proceed for an Orientation City Tour visiting Houses of Parliament, the Castle, Signal Hill, Sea Point, V&A Water Front & Malay Quarters. Later proceed for Helicopter Ride (Included) and evening free at leisure. Dinner and Overnight in Cape Town. DAY 03 : CAPE TOWN After breakfast we drive towards Hout Bay and take a boat trip to Seal Island a 45 minutes boat trip. The island is long and narrow, 800 meter long and only 50 meter wide. Some rock made by sealers in the 1930s are still evident. -

WIND SPEED POTENTIAL ASSESSMENT of SELECTED CLIMATIC ZONES of ETHIOPIA Endalew Ayenew1, Santoshkumar Hampannavar2 •

Endalew Ayenew RT&A, Special Issue № 1 (60) WIND SPEED POTENTIAL ASSESSMENT Volume 16, Janyary 2021 WIND SPEED POTENTIAL ASSESSMENT OF SELECTED CLIMATIC ZONES OF ETHIOPIA Endalew Ayenew1, Santoshkumar Hampannavar2 • 1College of Electrical & Mechanical Engineering, Addis Ababa Science and Technology University, Ethiopia Professor, School of Electrical and Electronics Engineering, REVA University, Bengaluru, India [email protected] Abstract In this paper the wind speed potential assessment of different climatic zones of Ethiopia are proposed. Statistical analysis of wind speed were carried out using Rayleigh and Weibull probability density functions (PDF) for a specific location. Real time Typical Meteorological Year (TMY) data was used for the wind speed potential assessment of three different climatic zones and to plot wind rose diagram. Keywords: Wind speed assessment, Statistical analysis, Wind Energy I. Introduction Wind is one of the globally recognized potential renewable energy source and it is important to have an inclusive knowledge about the wind characteristics for efficient planning and implementation of wind power generation plants. The wind energy assessment is very crucial and draws attention of researchers. Wind resources assessment is a basic requirement for the following reasons: i) wind power is proportional to the cube of the wind speed (10% difference in wind speed leads to 33% changes in wind power), ii) fluctuating wind speed and wind shears. According to the statistics the country has existing wind energy capacity of about 18.7GW with wind speed of 7.5 to 8.8 m/s at 50m height above the ground level. Wind energy is recognized throughout the world as a cost-effective energy plant. -

UN Session on GERD Dispute Strains Egypt-Russia Relations by Haisam Hassanein

MENU Policy Analysis / Policy Alert UN Session on GERD Dispute Strains Egypt-Russia Relations by Haisam Hassanein Aug 17, 2021 Also available in Arabic ABOUT THE AUTHORS Haisam Hassanein Haisam Hassanein was the 2016–17 Glazer Fellow at The Washington Institute. Brief Analysis Moscow is keen on courting Ethiopia, and Cairo is beginning to realize its partner’s limitations, yet the two governments will nevertheless continue cooperating on hot-button issues like weapons procurement. n August 5, Russian ambassador Georgiy Borisenko appeared on Egypt’s Ten TV to respond to local media O campaigns against his country. Much of the criticism has stemmed from Moscow’s unfriendly stance toward Cairo during last month’s UN Security Council deliberations on the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD). Amid the strongest bilateral tensions seen in years, Borisenko emphasized four points: 1. That Russia will pursue a balanced policy regarding the GERD and will mediate disagreements between its allies in Cairo and Addis Ababa if asked. 2. That Moscow deeply appreciates its military cooperation with Egypt but is concerned about the country’s participation in a June military exercise in the Black Sea region alongside the United States and Ukraine. 3. That Russia still views the Egyptian-hosted East Mediterranean Gas Forum as an energy competitor but will consider joining as an observer. 4. That the “terrorist” Muslim Brotherhood media based in London is responsible for spreading false rumors about strained bilateral relations. The tensions first came to light on July 8, when Russian representative Vasily Nebenzya told the Security Council that diplomatic means are the only solution for disputes surrounding the GERD, and that “statements about using force should be avoided and prevented.” This line was interpreted negatively in Cairo because it directly challenged statements from President Abdul Fattah al-Sisi, who had been insinuating for months that a military confrontation was possible. -

Countries and Their Capital Cities Cheat Sheet by Spaceduck (Spaceduck) Via Cheatography.Com/4/Cs/56

Countries and their Capital Cities Cheat Sheet by SpaceDuck (SpaceDuck) via cheatography.com/4/cs/56/ Countries and their Captial Cities Countries and their Captial Cities (cont) Countries and their Captial Cities (cont) Afghani stan Kabul Canada Ottawa Federated States of Palikir Albania Tirana Cape Verde Praia Micronesia Algeria Algiers Cayman Islands George Fiji Suva American Samoa Pago Pago Town Finland Helsinki Andorra Andorra la Vella Central African Republic Bangui France Paris Angola Luanda Chad N'Djamena French Polynesia Papeete Anguilla The Valley Chile Santiago Gabon Libreville Antigua and Barbuda St. John's Christmas Island Flying Fish Gambia Banjul Cove Argentina Buenos Aires Georgia Tbilisi Cocos (Keeling) Islands West Island Armenia Yerevan Germany Berlin Colombia Bogotá Aruba Oranjestad Ghana Accra Comoros Moroni Australia Canberra Gibraltar Gibraltar Cook Islands Avarua Austria Vienna Greece Athens Costa Rica San José Azerbaijan Baku Greenland Nuuk Côte d'Ivoire Yamous‐ Bahamas Nassau Grenada St. George's soukro Bahrain Manama Guam Hagåtña Croatia Zagreb Bangladesh Dhaka Guatemala Guatemala Cuba Havana City Barbados Bridgetown Cyprus Nicosia Guernsey St. Peter Port Belarus Minsk Czech Republic Prague Guinea Conakry Belgium Brussels Democratic Republic of the Kinshasa Guinea- Bissau Bissau Belize Belmopan Congo Guyana Georgetown Benin Porto-Novo Denmark Copenhagen Haiti Port-au -P‐ Bermuda Hamilton Djibouti Djibouti rince Bhutan Thimphu Dominica Roseau Honduras Tegucig alpa Bolivia Sucre Dominican Republic Santo -

CAIRO to ADDIS ABABA (38 Days) Nile Trans

CAIRO to ADDIS ABABA (38 days) Nile Trans COUNTRIES VISITED: EGYPT, ETHIOPIA, SUDAN INCLUDES • Accommodation - approx. 85% camping & 15% simple hostels/hotels • Pyramids & Sphinx day tour & guide • Lake Nasser Ferry • Entry into Meroe Pyramids • Meals - approx. 60% • All Transport on Oasis Expedition Truck • Camping and Cooking equipment • Services of Oasis Crew EXCLUDES • Visas • Optional Excursions as listed in the Pre-Departure Information • Flights • Airport Taxes & Transfers • Travel Insurance www.oasisoverland.co.uk PAGE 1 [email protected] Tel: +44 (0)203 725 8924 • Meals - approx. 40% • Drinks • Tips TRIP ITINERARY DAYS 1 - 4 CAIRO TO LUXOR The first part of our day is spent in Cairo visiting the great Pyramids and Sphinx at Giza with our Egyptologist guide, and also the Egyptian Museum. We then drive towards the Red Sea Coast. You will have time relax on the beach or try your hand at various watersports such as snorkelling, windsurfing or scuba diving in the cool clear blue waters. We end our first few days in the city of Luxor where the Valley of Kings and Queens and Karnak and Luxor Temples will keep us busy exploring for a few days more. DAYS 5 - 14 LUXOR TO ABU SIMBEL Here in Luxor - you have the opportunity to visit the Valley of Kings and Queens, the remarkably well preserved tombs of ancient rulers such as Ramses lV and Tutankhamun have coloured paintings and hieroglyphics that still seem fresh even after 3000 years. Karnak and Luxor Templesare both in easy walking distance from our camp - as is the local souq where you can pick up an array of souvenirs. -

Djibouti: Z Z Z Z Summary Points Z Z Z Z Renewal Ofdomesticpoliticallegitimacy

briefing paper page 1 Djibouti: Changing Influence in the Horn’s Strategic Hub David Styan Africa Programme | April 2013 | AFP BP 2013/01 Summary points zz Change in Djibouti’s economic and strategic options has been driven by four factors: the Ethiopian–Eritrean war of 1998–2000, the impact of Ethiopia’s economic transformation and growth upon trade; shifts in US strategy since 9/11, and the upsurge in piracy along the Gulf of Aden and Somali coasts. zz With the expansion of the US AFRICOM base, the reconfiguration of France’s military presence and the establishment of Japanese and other military facilities, Djibouti has become an international maritime and military laboratory where new forms of cooperation are being developed. zz Djibouti has accelerated plans for regional economic integration. Building on close ties with Ethiopia, existing port upgrades and electricity grid integration will be enhanced by the development of the northern port of Tadjourah. zz These strategic and economic shifts have yet to be matched by internal political reforms, and growth needs to be linked to strategies for job creation and a renewal of domestic political legitimacy. www.chathamhouse.org Djibouti: Changing Influence in the Horn’s Strategic Hub page 2 Djibouti 0 25 50 km 0 10 20 30 mi Red Sea National capital District capital Ras Doumeira Town, village B Airport, airstrip a b Wadis ERITREA a l- M International boundary a n d District boundary a b Main road Railway Moussa Ali ETHIOPIA OBOCK N11 N11 To Elidar Balho Obock N14 TADJOURA N11 N14 Gulf of Aden Tadjoura N9 Galafi Lac Assal Golfe de Tadjoura N1 N9 N9 Doraleh DJIBOUTI N1 Ghoubbet Arta N9 El Kharab DJIBOUTI N9 N1 DIKHIL N5 N1 N1 ALI SABIEH N5 N5 Abhe Bad N1 (Lac Abhe) Ali Sabieh DJIBOUTI Dikhil N5 To Dire Dawa SOMALIA/ ETHIOPIA SOMALILAND Source: United Nations Department of Field Support, Cartographic Section, Djibouti Map No. -

My Name Is Tyobista. I Grew up in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. I Went to a Catholic Girls School All Throughout My Elementary, Middle and High School

My name is Tyobista. I grew up in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. I went to a Catholic girls school all throughout my elementary, middle and high school. As a senior in high school, I realized that there is not much options in what I could study if I stayed in Ethiopia, so I decided to come to the U.S. I first attended La Salle University for a year and a half. La Salle was great but did not have the major I wanted and also did not offer me much financial aid so I transferred to Gettysburg College. I graduated cum laude and honors in my major from Gettysburg on May 17. While in Gettysburg I majored in Globalization Studies and I designed my own focus on post-conflict transformation and community development in Africa. I studied abroad in South Africa, did an internship in Ghana and conducted research and participated on immersion trip in Morocco. I was very active on campus and participated in various events and campus organizations. I was part of the diversity peer educators which was a campus organizations that promotes diversity and inclusion, I was the founding member of the Gettysburg African Student Association where we tried to show our presence on campus and help people learn about our different African cultures. I also worked a project leader for the leadership institute where I helped organize a semester long program where selected participants learn about the Little Rock Crisis and other civil right issues of the past and current times. Another project lead and I led the immersion trip to Abilene, Kansas and Little Rock, Arkansas, at the end of the semester where we took the participants to actually see everything they have learned about. -

Resolutions Adopted by the First Ordinary Session of the Assembly of Heads of State and Government Held in Cairo, Uar, from 17 to 21 July 1964

ORGANIZATION OF AFRICAN UNITY Secretariat Addis Ababa AHG/Res. 1 (1) - AHG/Res. 24 (1) RESOLUTIONS ADOPTED BY THE FIRST ORDINARY SESSION OF THE ASSEMBLY OF HEADS OF STATE AND GOVERNMENT HELD IN CAIRO, UAR, FROM 17 TO 21 JULY 1964 AHG/Res. 1(I) REPORT OF THE PROVISIONAL SECRETARY-GENERAL The Assembly of Heads of State and Government meeting in its First Ordinary Session in Cairo, U.A.R., from 17 to 21 July 1964, Having examined the Progress Report of the Provisional Administrative Secretary-General covering the period between September 1963 and July 1964, Takes note of the report. AHG/Res. 2(I) RECOMMENDATIONS OF THE FIRST AND SECOND ORDINARY SESSIONS OF THE COUNCIL OF MINISTERS The Assembly of Heads of State and Government meeting in its First Ordinary Session in Cairo, U.A.R., from 17 to 21 July 1964, Having reviewed the Resolutions and Recommendations of the First and Second Ordinary Sessions of the Council of Ministers, Adopts these Resolutions and Recommendations* *The Recommendation of the First Session of the Council of Ministers on the location of the Permanent Headquarters was put to a vote separately. The Assembly adopted by acclamation the Recommendation of the Council that Addis Ababa be the site for the Permanent Headquarters of the Organization of African Unity. AHG/Res. 3 (I) RECOMMENDATIONS OF THE FIRST AND SECOND EXTRAORDINARY SESSIONS OF THE COUNCIL OF MINISTERS The Assembly of Heads of State and Government meeting in its First Ordinary Session in Cairo, U.A.R., from 17 to 21 July 1964, Having reviewed the Resolutions and Recommendations of the First and Second Extra-ordinary Sessions of the Council of Ministers, Adopts these Resolutions and Recommendations. -

Covid-19 Response

WFP COMMON SERVICES COVID-19 RESPONSE Situation Report #3 | 11 August 2020 COVID-19 continues to pose challenges globally, causing severe interruptions to supply chains and logistics operations. To minimise the impact on humanitarian operations, WFP is using its logistics capacity and expertise within the framework of the Global Humanitarian Response Plan (GHRP) to support health and humanitarian partners as they respond to not only the global health response to COVID-19, but also to existing humanitarian crises around the world. HIGHLIGHTS 1,013 WFP/Jama Hassan PASSENGER FLIGHTS 18,209 PASSENGERS transported to 55 destinations * 44,654 m3 of cargo transported to 161 countries 316 ORGANIZATIONS supported through WFP Common Services *Via COVID-19 free-to-user cargo services under the Global Humanitarian Response Plan, WFP Bilateral Services and UNHRD dispatches (including those directly from suppliers) Monthly Passenger Trend, 1 May - 31 July 2020 Monthly Cargo Dispatch Trend, 1 February - 31 July 2020 (BSP, UNHRD, Free-to-User) Passenger Number m3 12,000 40,000 10,216 35,000 10,000 30,000 8,000 25,000 6,000 20,000 15,345 4,563 13,113 15,000 4,000 10,000 6,683 2,000 1,001 3,960 5,000 547 899 May June July February March April May June July Cargo dispatched monthly Cumulative cargo dispatched 1 WFP COMMON SERVICES COVID-19 RESPONSE AIR PASSENGER SERVICES WFP has commenced its first flights in the Latin Addis Ababa, Accra, Dar Es Salam, American region, marking an important milestone in its air passenger operations as the region continues Entebbe, Abuja, Niamey, Yaoundé, to be a hotspot for COVID-19 infections. -

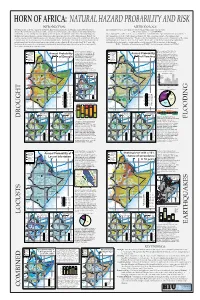

Flooding Locusts Drought Earthquakes Combined

HORN OF AFRICA: NATURAL HAZARD PROBABILITY AND RISK INTRODUCTION: METHODOLOGY: The Horn of Africa (HOA), composed of Djibouti, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Kenya, and Somalia, suffers frequent natural The probability of one or more hazard events occurring within a grid cell is given by disasters that commonly result in losses of life, destruction of infrastructure, and reduction of agricultural production. P(1 or more events) = 1 - exp(-E[N(HI)]), Formulating effective contingencies to respond to such emergencies is constrained by a limited understanding of the where E[N(HI)] = λ(HI)*T. E is the expected number of events within time T given historical rate of occurrence λ. likelihood of a natural hazard occurring within a particular region and risks associated with that hazard. Robust early The summation is over all events within a given grid cell. This calculation assumes a Poissonian, or time- warning systems exist for national response and "hot spot" maps of risk have been produced at a global level; this level of independent, distribution of probability. This means that the probability of a future event is independent of the timing resolution, however, is often not sufficient for sub-national resource distribution. This study presents the probabilities of and magnitude of the most recent events in the region. The measure of risk R(HI) is obtained by combining the natural hazards and the risk to populations or agricultural systems within the HOA, calculated on 1° by 1° grid cells. probability P(HI) of a hazard occurring with the societal exposure X(HI), or exposure, to that hazard: Such an analysis can provide a regional understanding of the probability of natural hazards as well as a more specific R(HI) = Probability of hazard occurring [P(HI)] * Societal exposure to that hazard [X(HI)]. -

The AU and the Search for Peace and Reconciliation in Burundi and Comoros

Th e AU and the search for Peace and Reconciliation in Burundi and Comoros The Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue (HD Centre) is an independent mediation organisation dedicated to helping improve the global response to armed confl ict. It attempts to achieve this by mediating between warring parties and providing support to the broader mediation community. The HD Centre is driven by humanitarian values and its ultimate goal to reduce the consequences of violent confl ict, improve security, and contribute to the peaceful resolution of confl ict. It maintains a neutral stance towards the warring parties that it mediates between and, in order to maintain its impartiality it is funded by a variety of governments, private foundations and philanthropists. © Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue, 2011 Reproduction of all or part of this publication may be authorised only with written consent and acknowledgement of the source. Front cover photography: © African Union, 78th PSC Meeting on Comoros, 9 June 2007 | © Lt. TMN Turyamumanya / Afrian Union, TFG Soldiers in Somalia queue for their fi rst organised payment exercise supervised by AMISOM troops in Mogadishu | © African Union, Water provision to neighbouring villagers in Mogadishu Th e AU and the search for Peace and Reconciliation in Burundi and Comoros Table of contents Part I Foreword 02 Acknowledgements 04 — Burundi case study Introduction 05 Part I: Burundi case study 09 Part II Executive summary 09 1.1 Context 10 case study — Comoros 1.2 OAU/AU intervention in the Burundi crisis 12 Part II: Comoros -

Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: Building an Improved Nmt Culture Through Bicycle Sharing

TUMI INITIATIVE’S TRANSFORMATIVE STORIES ADDIS ABABA, ETHIOPIA: BUILDING AN IMPROVED NMT CULTURE THROUGH BICYCLE SHARING The city of Addis Ababa is home to 25 percent of Ethiopians, and its population is projected to reach close to fi ve million by 2030. Considered one of the fastest growing urban settlements in the world, its planning and development is struggling to keep up with its rapid expansion. For citizens, moving around the city is a daily challenge due to traffi c caused by congestion and frequent accidents, insuffi cient public transport and a lack of infrastructure to accommodate non-motorized transport (NMT). The city is now prioritizing the improvement and development of infrastructure to allow more people to travel by foot or bicycle. It has set itself the ambitious goal of having the largest bicycle sharing scheme on the continent, and will soon implement the fi rst phase of this project with support from TUMI. ABOUT ADDIS ABABA Addis Ababa is the capital city of Ethiopia, the seat of the African Union and other international organizations, and home to around 100 embassies. It is often called the “African Capital” due to its historical, diplomatic and political signifi cance. Located in the foothills of the Entoto Mountains and standing 7,726 feet (2,355 meters) above sea level, it is the third highest capital city in the world. The Addis Ababa City Administration aims to serve as a role model for the development of effi cient and sustainable transport systems that improve access for local residents while addressing global climate change. Moving forward, it will commit to investing in sustainable transport systems.