Cultural Ecosystem Services in St Helena

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Telephone Directory 2019

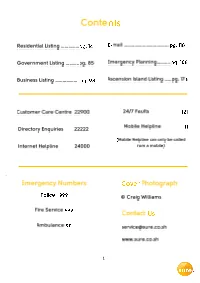

St Helena and Ascension Island Tel ephone Directory 2019 1 www.sure.co.sh [email protected] +290 22900 Contents: Residential Listing ……………….pg. 13 Customer Care Centre 22900 Government Listing …………….pg. 85 Directory Enquiries 22222 Business Listing …………………..pg. 98 Internet Helpline 24000 E-mail ……………………………….. pg. 119 Free SURE Service Numbers Emergency Planning…………..pg. 170 24/7 Faults 121 Ascension Island Listing ……. pg. 177 Mobile Helpline 111 (Mobile Helpline: can only be called from a mobile) Cover Photograph: © Craig Williams Emergency Numbers Police 999 Contacts: Fire Service 999 [email protected] Ambulance 911 www.sure.co.sh 1 About Us For over 114 years Sure South Atlantic (formally Cable and Wireless) has been providing connectivity to countries throughout the world via their national and internat ional telecoms networks. Today, Sure South Atlantic Limited is licensed by the St Helena Government to provide international public telecommunications services to the Island of St Helena. Our services include National & International Telephone, Public Internet and Television Re-Broadcast. Sure continues to invest in the network infrastructure on St Helena and our international satellite links, enabling us to offer robust, high quality communication services for both residential and business customers. In April 2013 the company was acquired by the Batelco Group, a leading telecommunications provider to 16 markets spanning the Middle East & Northern Africa, Europe and the South Atlantic and Indian Ocean. This marks the start of an exciting new phase for our business, as we join an international organization which is committed to delivering value and unsurpassed customer service. To underpin the important changes to our business, with effect from 15th July 2013 we changed our name from Cable & Wireless South Atlantic Ltd to Sure South Atlantic Limited. -

St Helena Celebrates Cultural Diversity on St Helena's

www.sams.sh THE South Atlantic Media Services, Ltd. Vol. 9,SENTINEL Issue 10 - Price: £1 “serving St Helena and her community worldwide” Thursday 27 May 2021 St Helena celebrates Cultural Diversity on St Helena’s Day Proposals to allow wealthy people purchase Permanent Residency “well received” say SHG The Global Saint Community New Burial Ground identified for Map by Saint Cooks “Liberated Africans” 2 www.sams.sh Thursday 27 May 2021 | THE SENTINEL THE SENTINEL | Thursday 27 May 2021 www.sams.sh 3 OPINION YOUR LETTERS ST HELENA NEWS SENTINEL Quiet Magistrate’s Court £2m under spend in SHG budget session predicted COMMENT Andrew Turner, SAMS Andrew Turner, SAMS Andrew Turner, SAMS overseas medical referral budget St Helena’s future is now resting and the TC budget not being fully in the hands of the UK Governments utilised. Privy Council who will decide on There was also an over collection the constitutional amendments of customs duties and an under needed to change St Helena from its collection in revenue in the Children current system of Governance to the and Adults Social Care Directorate Ministerial System. of £54k because fewer individuals Amendments to St Helena’s are eligible/able to pay for care constitution can only be made by services. a UK Order in Council which is an Order made by the Queen acting on According to the report of the the advice of the Privy Council. meeting, “Deputy Financial But what is the Privy Council and Secretary explained that there is this really the right group to be might be further changes to the deciding our fate? It was a comparatively quiet Thomas “in a hostile manner.” SHG is predicting an under spend of £2m was indicated, which was final outturn position as year-end Essentially the Privy Council is an session of the St Helena Magistrates According to the Magistrates of £2m for this financial year. -

Cultural Ecosystem Services in St Helena

South Atlantic Natural Capital Project; Cultural ecosystem services in St Helena. Dimitrios Bormpoudakis Robert Fish Dennis Leo Ness Smith April 2019 Review table Name Reviewed by Date Version 1 Ness Smith 17/04/19 Version 2 Tara Pelembe and Paul 30/04/19 Brickle Version 3 SHG 16/05/19 Version 4 Acknowledgements: We would like to thank the NCA project St Helena Advisory Group and everyone who took part in the survey. This research was funded by The UK Government via the Conflict, Security and Stability Fund. Suggested citation: Bormpoudakis, D., Fish, R., Leo, D., Smith, N. (2019). Cultural Ecosystem Services in St Helena. Final Report for the South Atlantic Overseas Territories Natural Capital Assessment For more information, please contact the South Atlantic Environmental Research Institute (SAERI) at [email protected] or visit http://south-atlantic-research.org PO Box 609, Stanley Cottage Stanley FIQQ 1ZZ Falkland Islands Tel: +500 27374 www.south-atlantic-research.org SAERI is a registered Charity in England and Wales (#1173105) and is also on the register of approved Charities in the Falkland Islands (C47). SAERI also has a wholly-owned trading subsidiary – SAERI (Falklands) Ltd – registered in the Falkland Islands. CULTURAL ECOSYSTEM SERVICES IN THE ISLAND OF ST HELENA Dimitrios Bormpoudakis & Robert Fish, School of Anthropology and Conservation, University of Kent Dennis Leo, St Helena National Trust Ness Smith, South Atlantic Environment Research Institute Version 3.0 – 21 May 2019 --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 1. BACKGROUND ON ST HELENA Saints know the value of nature; we want to turn this knowledge into data that will help in decision making across a range of sectors. -

April GAZ 2014.Pmd

The St. Helena Government Gazette Vol. XLXII. Published by Authority No. 28. Annual Subscription Present Issue £13.75 Post Free 30 April 2014 £1.25 per copy No. Contents Page 51.APPOINTMENTS AND STAFF CHANGES ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 207 52.APPOINTMENT OF ACTING ADMINISTRATOR, ASCENSION ISLAND... ... ... ... ... 208 53.APPOINTMENT OF DIRECTORS TO ENTERPRISE ST HELENA BOARD OF DIRECTORS ... ... 209 54.APPOINTMENT OF DEPUTY COMMISSIONER OF INCOME TAX ... ... ... ... ... 209 55.APPOINTMENTS OF COLLECTOR OF CUSTOMS AND EXCISE AND DEPUTY COLLECTOR OF CUSTOMS AND EXCISE ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 209 56.APPOINTMENTS OF MEMBERS AND DEPUTY CHAIRMEN OF COUNCIL COMMITTEES ... ... 210 57.APPOINTMENT OF ACTING ADMINISTRATOR, ASCENSION ISLAND ... ... ... ... ... 210 58. ST HELENA COMPANIES REGISTRY ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 210 59. CORRECTION TO GAZETTE NOTICE NO 24 DATED 31 MARCH 2014... ... ... ... ... 211 No.51. APPOINTMENTS AND STAFF CHANGES His Excellency the Governor has approved the following appointments and staff changes from the dates shown: Appointments Mrs Kerry Yon, Assistant Director (Life Long Learning) Education and Employment Directorate... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 1 April 2014 Mrs Wendy Benjamin, Assistant Director (Schools) Education and Employment Directorate... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 1 April 2014 Miss Kathryn Squires, Advisory Teacher English, Education and Employment Directorate... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 1 April 2014 Mr Clarence Youde, Maintenance Worker, Environment -

Sentinel 120906

THE St Helena Broadcasting (Guarantee) Corporation Ltd. www.shbc.sh Vol. SENTINEL1, Issue 24 - Price: £1“serving St Helena and her community worldwide” Th ursday 6 September 2012 THINGS THAT GO BUMP IN THE NIGHT Accident on Also in this Deadwood Plain issue: New babies, page 2&3 Darrin Henry, SHBC Second Maths Advisory On Monday evening 3 September, at approximate- Teacher appointed, page 2 ly 6.45, Basil Read’s 70 tonne excavator snagged on overhead power lines on Deadwood Plain, pull- Architects on St Helena, ing over an electricity pole and plunging the ma- jority of the island into darkness with a power cut page 6 that lasted more than 2 hours. No one was reported hurt although different eye- Opening reception held witnesses reported a bright fl ash seen on the Plain, at Longwood House, clearly visible from the Alarm Forest and Gor- page 11 don’s Post area. The power outage affected most districts across the island, including St Pauls, Blue Hill, Sandy Sports Arena: Bay, Levelwood, Alarm Forest and Longwood. Blue Hartz & Rastas The incident occurred as Basil Read were begin- through in rounders ning the process of moving heavy plant equipment knockout to the airport site now that the haul road from Ruperts to Deadwood Plain is open. The aim on Rovers drop fi rst points Monday was to get the equipment as far as Fox’s Raiders 5th victory of the Garage. season Island Director for Basil Read, Deon De Jager, Also, skittles, shooting, and Janet Lawrence, SHG Airport Director, both volleyball and golf news confi rmed a safety ‘banksman’ was escorting the excavator at the time of the accident. -

Rebecca Lawrence Becomes First St Helenian Veterinary Doctor

THE South Atlantic Media Services, Ltd. www.sams.sh Vol. 6,SENTINEL Issue 18 - Price: £1 “serving St Helena and her community worldwide” Thursday 03 August 2017 Rebecca Lawrence becomes fi rst St Helenian veterinary doctor “As a Saint, I hope this proves that what we have at home is enough for people to achieve high standards,” she said. “If you don’t think too much of yourself, and are willing to make sacrifi ces and put in the work, then I think St Helena is a great place to come from.” ... page 13 Bahamas Team Returns Schools Open Days Rosie... page Bargo 13 talks about A look back at car ... page 30-32 her new cocktail bar history on St Helena ... page 5 ... page 14 First Formal Legislative Council Meeting ... page 4 2 www.sams.sh Thursday 03 August 2017 | THE SENTINEL ST HELENA SNIPPETS Photo 2: The usual way to get large cargo from Snapshots the RMS onto the wharf. Photo by Emma Weaver. of the week News bites from this work week Emma Weaver, SAMS Monday, July 31 Pilling Open Day: (see page 30) Digital Strategy Draft public consultation meeting: 7pm in the Jamestown Community Centre worsen.” Public Library Closes Temporarily: “The The RMS fi nally departed St Helena, head- Public Library in Jamestown will be closed Tuesday, August 1 ed to Ascension, at 18:05 with 54 passengers temporarily from Wednesday, 2 August 2017, Rainbow of St James Bay: See Photo 1. A (who had boarded at noon) and 56 crew on- to allow renovation works to take place. -

Sentinel 27 June 2013

THE South Atlantic Media Services, Ltd. www.sams.sh Vol. 2,SENTINEL Issue 14 - Price: £1 “serving St Helena and her community worldwide” Th ursday 27 June 2013 L-R Carlos Yon, Lee Yon, Patrick Young, Pamela Young & Martin Buckley When the RMS St Helena de- parted the Island on Friday, it took St Helena’s NatWest Small Island Games team on their fi rst leg of their journey to Bermuda. The team will St Helena Athletes arrive in good time to be among the many islands taking part in the Opening Ceremony before the se- rous business of the competition starts from the 13 to 19 July. Bermuda Bound continued on page13 THE HEAT IS ON Again there has been movement on the GOVERNOR COMFIRMS ISLAND TO GO TO THE POLLS Election front this week, as three new names get added to the unoffi cial SAMS confi rmed list; Cyril George, Brenda Moors-Clingham and Raymond Williams. The race has heat- ed up and now it looks as if there will defi - nitely be a General election on 17 July. With more and more candidates stepping up and entering the race, we are nearing the magic number thirteen. Only when thir- teen or more candidates stand will there be a general election where the people will be asked to go to the polls and vote for the chosen candidates. In the recent Exco report the Governor mentioned that as many as 16 people have shown interest in running. Brenda Moors-Clingham continued on page 7 Raymond Williams Cyril George Dottie come home pg 3 Corona celebrates diamond jubillee pg 6 Lifestyle & Culture - Ivylettes pg 14 2 www.sams.sh Th ursday 27 June 2013 THE SENTINEL ST HELENA SNIPPETS BABY NEWS The stork delivered baby girl, Laila-Rose Hudson on Wednesday, 22 May at 10.10am. -

SAINTS Spatial Identities of the Citizens of Saint Helena

SAINTS Spatial identities of the citizens of Saint Helena Master’s thesis Human Geography University of Utrecht – the Netherlands By Maarten Hogenstijn Daniël van Middelkoop 1 SAINTS: SPATIAL IDENTITIES OF THE CITIZENS OF SAINT HELENA TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter 1 Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 5 1.1 Where? ............................................................................................................................................ 5 1.2 Why? ............................................................................................................................................... 5 1.3 Central question .............................................................................................................................. 6 Chapter 2 Theoretical framework ............................................................................................................... 8 2.1 Insularity ......................................................................................................................................... 8 2.1.1 Insularity and economy .............................................................................................................. 8 2.1.2 Insularity and peripherality......................................................................................................... 9 2.1.3 Insularity and social structure.................................................................................................. -

The Sentinel 29 September 2016

THE South Atlantic Media Services, Ltd. www.sams.sh Vol. 5,SENTINEL Issue 26 - Price: £1 “serving St Helena and her community worldwide” Thursday 29 September 2016 HISTORIC TREE REMOVED Castle Gardens only GREAT COMMITMENT 6 nurses take on studying a degree alongside a full-time job Banyan Tree Removed see page 11 due to Weevil Infestation Andrew Turner, SAMS Forestry work has been ongoing in the Castle Gardens this week. As part of this trees are being pruned and checked to see if they are healthy. During one of these routine checks it was dis- covered that the Garden’s only banyan tree had become infested with weevils. As weevils only house themselves in already dead trees it had be- come necessary to remove the tree completely to protect both the public and neighbouring trees. ANRD Forestry Offi cer Mira Young told The Sen- tinel “This is part of our annual program, the gar- dens are crown estates and we have responsibility for the trees. The aim is to keep the trees safe for users of the public gardens,” The wood from this tree will be fi rst offered to craftsmen who want to work with the wood. Any wood left over will be used either for fi rewood or chipped and made into a mulch that can be used as a fertiliser. The Forestry Division will continue with their pruning work through Jamestown over the com- ing weeks. Members of the ANRD forestry team 2 www.sams.sh Thursday 29 September 2016 | THE SENTINEL ST HELENA SNIPPETS Grand Fish-Fry on Longwood Green Engaging with the Community sisting of a selection of fresh fi sh, chips, yam, Ferdie Gunnell, SAMS etc. -

Examples of Risks on St Helena Include

1 2 3 4 • • • • • • • • • 5 6 7 ? 8 9 10 11 12 13 RESIDENTIAL CATEGORY ALPHABETICAL LISTING 14 A ADAMS, Anita & Alexander Clay Gut, Half Tree Hollow 23452 ADAMS, Barbara Nr Princes Lodge, St. Pauls 25575 ADAMS-DUNCAN, Jayne Hunts Vale, Alarm Forest 24917 ALLEN, Robert & Delia Lower Farm Lodge, St. Pauls 24440 ANDERSON, Nicola Sapper Way, St. Pauls 23417 ANDERSON, Patrick Rock Rose, Sandy Bay 24859 ANDREWS, Ann No. 3 R.E. Yard, Ladder Hill 23881 ANDREWS, Brian Wireless Station Road, Half Tree Hollow 23955 ANDREWS, Dorothy New Ground, St. Pauls 24036 ANDREWS, Fredrica Millfield, Longwood 24513 ANDREWS, Gemma Upper Cow Path, Nr High Knoll 25366 ANDREWS, Isabel Nr Evergreen Tree, Half Tree Hollow 23152 ANDREWS, Jessina The Boot, Longwood 25618 ANDREWS, Johnny Johants, New Ground 23040 ANDREWS, Kenickie S The Boot, Longwood 23957 ANDREWS, Kenneth Half Tree Hollow 23879 ANDREWS, Merrill Deadwood, Longwood 24975 ANDREWS, Patrick Cow Path, Half Tree Hollow 23021 ANDREWS, Roy & Jennifer Nr White Wall, Half Tree Hollow 23019 ANDREWS, Sidonio S Oasis Bar, Cow Path 23607 ANDREWS, Sonny No. 4 Cow Path, Half Tree Hollow 23880 ANDREWS, Steven No. 4 Cow Path, Half Tree Hollow 25439 ANNIES LAUNDRETTE, Napoleon Street, Jamestown 22435 c/o Anne Wolstenholme ANNS PLACE, Jane Sim Castle Gardens, Jamestown 22797 ANTHONY, Cecil Half Tree Hollow 23993 ANTHONY, Eileen No. 5 Barracks Square, Jamestown 22581 ANTHONY, Jolene No. 5 Harris Flats, Jamestown 25502 ANTHONY, Neil James Nr Longwood Clinic, Longwood 23728 ANTHONY, Patrick White Gate, St Pauls 23287 ANTHONY, Robert J Red Hill, Nr High Knoll 23971 15 A ANTHONY, Stephen Ladder Hill, Half Tree Hollow 23015 ANTHONY, Sylvia Nr. -

Vet Joe Hollins Explains Egg Shortage Causes and Solutions

www.sams.sh THE South Atlantic Media Services, Ltd. Vol. 10,SENTINEL Issue 06 - Price: £1 “serving St Helena and her community worldwide” Thursday 06 May 2021 Vet Joe Hollins explains egg shortage causes and solutions Anniversaries: Napoleon’s bicentenary, British colonisation SHG IT takes first company go-karting crown New Census results: Second highest aging pop. in the world? St Helena Airport welcomes MV Helena Voyage 41: another big group of young Charges to increase visitors £225/container 2 www.sams.sh Thursday 06 May 2021 | THE SENTINEL THE SENTINEL | Thursday 06 May 2021 www.sams.sh 3 OPINION YOUR LETTERS YOUR LETTERS Dear Editor far greater sympathy for their Introduction: 1 month’s quarantine) – but but Titan switched to a Boeing, SENTINEL hostile neighbour, Argentina, This is a brief summary of that it was also temporary. It is which can. However: Mark Mardell correctly points than for them. While Brexiteers the issues that have developed a projection of egg production o Most of the Titan flights leave out that Gibraltar was the only are still prepared to defend them recently in keeping the island versus egg consumption. The red just after midnight between British Overseas Territory to be COMMENT militarily, they have hit them stocked with egg laying pullets and green lines have been added to Sunday/Monday – Sunday is the part of the EU, but others are not Andrew Turner, SAMS economically. for local production of eggs. illustrate when the apparent glut one day of the week that there is unscathed by Brexit. But tempting as it is to mock Local production is desirable of eggs would become a shortage. -

The Sentinel 8 September 2016

THE South Atlantic Media Services, Ltd. www.sams.sh Vol. 5,SENTINEL Issue 23 - Price: £1 “serving St Helena and her community worldwide” Thursday 8 September 2016 BUCKLEY GETS IN Damien O’Bey, SAMS Cruyff Gerard Buckley of Half Tree Hollow became the newest member of Legislative Council after St Helena went to the polls on Wednesday 7 September. Buckley won 170 (39%) of the total votes cast on the day to become the youngest elected member since a 23 year old Tara Wortley became a member of Executive Council in 2009. continued on page 4 KEEPING PROMISES St James Church gets a New Steeple see page 3 2 www.sams.sh Thursday 8 September 2016 | THE SENTINEL ST HELENA SNIPPETS Cheeky Grin Donna Crowie, SAMS Parker Logan Yon - Stevens Very proud parents Kim Yon and Travoy Stevens were over the moon when baby Parker made an entrance to the world on Saturday 13 August 2016 at 6:58pm, weighing 6lb 1oz. Mummy says “Parker is doing really well and has settled in to a routine.” Daddy is also proud and happy to have his little boy and Parker's sister Santina is very happy to have a baby brother. “Mummy is feeling good and not tired at the moment” she said with a laugh. The couple would like to thank Doctor Francisco, Mid- wives Jenny Turner, Rosie Mittens and Erica Bowers and mum Bronwen for the help and support given during the quick delivery. Thanks are also ex- tended to all family and friends who sent greetings and gifts.