Spring Owner's Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spring 2021 | Issue No

SPRING 2021 | ISSUE NO. 31 THE CANAL QUARTERLYwww.CanalTrust.org CANAL STEWARDS PROVIDE VITAL SERVICE One of the largest contributions the C&O Stewards perform many types of light Canal Trust makes to the C&O Canal National maintenance tasks, including lopping and Historical Park is the volunteer support pruning, painting, picking up trash, removing we marshal and manage. As the Park's vegetation, raking, and restocking maps and official nonprofit partner, we are focused on trash-free park bags. It's the perfect way for providing volunteer efforts to aid National an individual, couple, or small group to get Park Service (NPS) staff in maintenance and fresh air, exercise, and care for the Park, all beautification projects along the towpath. while social distancing. Every garden mulched and invasive plant pulled by a volunteer is one less chore for an Stewards are able to set their own schedules NPS maintenance worker, freeing him or her in cooperation with the Trust's Canal up for higher-level responsibilities. Stewards Coordinator Becka Lee. Volunteers are required to go through an orientation In late 2020, the Trust added a new volunteer program prior to beginning work at their program to our arsenal, the Canal Stewards site. If you choose to become a Steward, program, which we assumed management you will join the hundreds of dedicated of from NPS staff. Canal Stewards "adopt" volunteers who work to keep the Park clean a section of the canal and maintain it for and safe for its nearly 5 million visitors. For a designated time period. Parking lots, more information, visit www.canaltrust. -

Flood Pulse Effects on Benthic Invertebrate Assemblages in the Hypolacustric Interstitial Zone of Lake Constance

Ann. Limnol. - Int. J. Lim. 48 (2012) 267–277 Available online at: Ó EDP Sciences, 2012 www.limnology-journal.org DOI: 10.1051/limn/2012008 Flood pulse effects on benthic invertebrate assemblages in the hypolacustric interstitial zone of Lake Constance Shannon J. O’Leary1 and Karl M. Wantzen2* 1 School of Marine and Atmospheric Sciences, Stony Brook University, Stony Brook, NY 11733, USA 2 CNRS UMR 6371 CITERES/IPAPE, De´partement des Sciences, Universite´Franc¸ois Rabelais, Parc Grandmont, 37200 Tours, France Abstract – In contrast to rivers, the effects of water level fluctuations on the biota are severely understudied in lakes. Lake Constance has a naturally pulsing hydrograph with average amplitudes of 1.4 m between winter drought and summer flood seasons (annual flood pulse (AFP)). Additionally, heavy rainstorms in summer have the potential to create short-term summer flood pulses (SFP). The flood pulse concept for lakes predicts that littoral organisms should be adapted to the regularly occurring AFP, i.e. taking advantage of benefits such as an influx of food sources and low predator pressure, though these organisms will not possess adapta- tions for the SFP. To test this hypothesis, we studied the aquatic invertebrate assemblages colonizing the gravel sediments of Lake Constance, the AFP in spring and a dramatic SFP event consisting of a one meter rise of water level in 24 h. Here, we introduce the term ‘hypolacustric interstitial’ for lakes analog to the hyporheic zone of running water ecosystems. Our results confirm the hypothesis of contrasting effects of a regular AFP and a random SFP indicating that the AFP enhances the productivity and biodiversity of the littoral zone with benthic invertebrates displaying an array of adaptations enabling them to survive. -

Springs of California

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY GEORGE OTIS SMITH, DIBECTOB WATER- SUPPLY PAPER 338 SPRINGS OF CALIFORNIA BY GEKALD A. WARING WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1915 CONTENTS. Page. lntroduction by W. C. Mendenhall ... .. ................................... 5 Physical features of California ...... ....... .. .. ... .. ....... .............. 7 Natural divisions ................... ... .. ........................... 7 Coast Ranges ..................................... ....•.......... _._._ 7 11 ~~:~~::!:: :~~e:_-_-_·.-.·.·: ~::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: ::::: ::: 12 Sierra Nevada .................... .................................... 12 Southeastern desert ......................... ............. .. ..... ... 13 Faults ..... ....... ... ................ ·.. : ..... ................ ..... 14 Natural waters ................................ _.......................... 15 Use of terms "mineral water" and ''pure water" ............... : .·...... 15 ,,uneral analysis of water ................................ .. ... ........ 15 Source and amount of substances in water ................. ............. 17 Degree of concentration of natural waters ........................ ..· .... 21 Properties of mineral waters . ................... ...... _. _.. .. _... _....• 22 Temperature of natural waters ... : ....................... _.. _..... .... : . 24 Classification of mineral waters ............ .......... .. .. _. .. _......... _ 25 Therapeutic value of waters .................................... ... ... 26 Analyses -

Mineral Springs Walking Tour

The Springs Early advertisement for Steamboat’s springs of Steamboat Springs An elk takes a swim in the Heart Spring pool YOUR EXploration OF THE SPRINGS DISCOVER Steamboat’S SPRINGS: can be tailored to your own curiosity level. By starting IRON SPRING at Iron Spring you are within easy walking distance (about one mile) of five mineral springs. For the more SODA SPRING adventuresome—extend your tour with a hike to SULPHUR SPRING the Sulphur Cave or take a plunge in the “soothing SWEETWATER/LAKE SPRING and health-giving” waters of the Old Town Hot Springs. STEAMBOAT SPRING NARCISSUS/TERRACE SPRING Journey in the footsteps of the Yampatika Ute and BLACK SULPHUR SPRING Arapaho tribes and the early pioneers of Steamboat LITHIA SPRING Springs as you discover the city’s mineral springs. No two springs are alike—and each has its own SULPHUR CAVE special mineral content and intriguing allure. HEART SPRING at THE OLD TOWN HOT SPRINGS Use this map for guidance, as the new trail differs from the Please be advised that the waters in these springs are natural one on the blue signs located at each spring. Suitable walking flowing and untreated. Drinking from the springs may cause shoes are advised since parts of the trail are rough and steep. illness or discomfort. After touring the springs, see if you know which is the: For more information about the springs in Steamboat Springs please visit or call: • Hottest spring? • Tread of Pioneers Museum ~ 8th and Oak 970.879.2214 • Lemonade spring? • City of Steamboat Springs ~ 137 10th Street 970.879.2060 • Most odiferous spring? • Bud Werner Memorial Library ~ 12th and Lincoln 970.879.0240 • Yampatika ~ 925 Weiss Drive 970.871.9151 • Most palatable? This document is supported in part by a Preserve America grant administered by • Miraquelle spring? the National Park Service, Department of the Interior. -

Capitol Reef U.S

National Park Service Capitol Reef U.S. Department of the Interior Capitol Reef National Park Spring Canyon Spring Canyon is deep and narrow with towering Wingate cliffs and Navajo domes. It originates on the shoulder of Thousand Lakes Mountain and extends to the Fremont River. The route is marked with rock cairns and signs in some places, but many sections are unmarked and car- rying a topographic map and GPS unit is recommended. It is extremely hot in summer, and the only usually reliable water source is at the spring in Upper Spring Canyon, 1.5 miles (2.41 km) west of the junction with Chimney Rock Canyon. Use caution in narrow canyons particular- ly during the flash flood season (typically July–September). The canyon route is divided into Upper and Lower Spring Canyon sections. It can be accessed midway via Chimney Rock Canyon. The entire canyon is best done as a three- to four-day trip. Upper Spring Canyon is a good two- to three- day trip, while Lower Spring Canyon can be done as an overnight or long day hike. Backcountry permits are required for all overnight trips and can be obtained at the visitor center. Location of Trailheads 1. Upper end of Spring Canyon: Holt Draw, which is a dirt track on the right (north) side of Hwy 24, 0.9 miles (1.44 km) west of the park boundary and 7.2 miles (11.59 km) west of the visitor center. The road is closed to vehicle traf- fic beyond the gate at the forest service boundary near Hwy 24. -

The Legendary Lore of the Holy Wells of England

'? '/-'#'•'/ ' ^7 f CX*->C5CS- '^ OF CP^ 59§70^ l-SSi"-.". -,, 3 ,.. -SJi f, THE LEGENDARY LORE OF THE HOL Y WELLS OF ENGLAND. : THE LEGENDARY LORE ' t\Q OF THE ~ 1 T\ I Holy Wells of England: INCLUDING IRfpers, Xaftes, ^fountains, ant) Springs. COPIOUSLY ILLUSTRATED BY CURIOUS ORIGINAL WOODCUTS. ROBERT CHARLES HOPE, F.S.A., F.R.S.L., PETERHOUSE, CAMBRIDGE; LINCOLN'S INN; MEMBER,OF THE COUNCIL OF THE EAST RIDING OF YORKSHIRE ANTIQUARIAN SOCIETY, AUTHOR OF "a GLOSSARY OF DIALECTAL PLACE-NOMENCLATURE," " AN INVENTORY OF THE CHURCH PLATE IN RUTLAND," "ENGLISH GOLDSMITHS," " THE LEPER IN ENGLAND AND ENGLISH LAZAR-HOUSES ;" EDITOR OF BARNABE GOOGE'S " POPISH KINGDOME." LONDON ELLIOT STOCK, 62, PATERNOSTER ROW, E.C. 1893. PREFACE, THIS collection of traditionary lore connected with the Holy Wells, Rivers, Springs, and Lakes of England is the first systematic attempt made. It has been said there is no book in any language which treats of Holy Wells, except in a most fragmentary and discursive manner. It is hoped, therefore, that this may prove the foundation of an exhaustive work, at some future date, by a more competent hand. The subject is almost inexhaustible, and, at the same time, a most interesting one. There is probably no superstition of bygone days that has held the minds of men more tenaciously than that of well-worship in its broadest sense, "a worship simple and more dignified than a senseless crouching before idols." An honest endeavour has been made to render the work as accurate as possible, and to give the source of each account, where such could be ascertained. -

Impacts of a Flood Pulsing Hydrology on Plants and Invertebrates in Riparian Wetlands

IMPACTS OF A FLOOD PULSING HYDROLOGY ON PLANTS AND INVERTEBRATES IN RIPARIAN WETLANDS A dissertation submitted to Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Maureen K. Drinkard August 2012 Dissertation written by Maureen K. Drinkard B.S., Kent State University, 2003 Ph.D., Kent State University, 2012 Approved by ___Ferenc de Szalay_, Chair, Doctoral Dissertation Committee ___Mark Kershner_______, Members, Doctoral Dissertation Committee _____Oscar Rocha________, ____Mandy Munro-Stasiuk_, Accepted by _____James Blank______, Chair, Department of Biological Sciences ______Raymond Craig___, Dean, College of Arts and Sciences ii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES ............................................................................................................... vi LIST OF TABLES ................................................................................................................. vii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .................................................................................................... x CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................ 1 Dissertation Goals ............................................................................................. 1 Definition of the Flood Pulse Concept .............................................................. 2 Ecological and economic importance ............................................................... 3 Impacts of environmental -

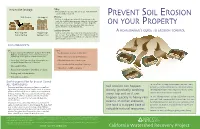

Prevent Soil Erosion on Your Property

How to Use Sandbags Filling Filling sandbags is best done with two people. Fill half full with sand if available or local soil. ������������ ���������� Stacking PREVENT SOIL EROSION Fold top of sandbag down and rest the bag on its top on the stack. Top should be facing upstream. Stamp the bag into place. Complete each layer before starting the next layer. Stagger the layers. Stack no more than three layers high unless they are ON YOUR ROPERTY against a building or stacked pyramid-style. P Sandbag diversion HOMEOWNER S GUIDE TO EROSION CONTROL ��������������� ������������� Sandbags will redirect water away from property but will not A ' �������������� ������������ seal out water. Place sandbags with the folded top toward the upstream or uphill direction. Sandbags are temporary and will deteriorate after several months. DO’S AND DON’TS Do: Don’t: • Contact your local Flood Control Agency or Public Works • Under-estimate the power of debris flows. Authority- Installing these erosion control devices on your property may not be sufficient to thwart extreme flows. • Walk or drive across swiftly flowing water. • Try to direct debris flows away from your property to a • Wait until storms arrive to make a plan. recognized drainage device or to the street. • Try to confine the flows more than is necessary. • Clear a path for debris. • Direct flow to neighbor’s property. • Place protective measures to divert debris, not dam it. • Board up windows facing the flow • Work with your neighbors. Don’t Forget to Plan for Erosion Control ALL YEAR ROUND In an effort to help landowners protect their Preventing runoff during the spring and summer is equally as Soil erosion can happen property, professional NRCS Conservationists important as preventing erosion. -

5.1 Coarse Bed Load Sampling

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1997 The initiation of coarse bed load transport in gravel bed streams Andrew C. Whitaker The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Whitaker, Andrew C., "The initiation of coarse bed load transport in gravel bed streams" (1997). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 10498. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/10498 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter free, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

Hydrogeologic Characterization and Methods Used in the Investigation of Karst Hydrology

Hydrogeologic Characterization and Methods Used in the Investigation of Karst Hydrology By Charles J. Taylor and Earl A. Greene Chapter 3 of Field Techniques for Estimating Water Fluxes Between Surface Water and Ground Water Edited by Donald O. Rosenberry and James W. LaBaugh Techniques and Methods 4–D2 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Contents Introduction...................................................................................................................................................75 Hydrogeologic Characteristics of Karst ..........................................................................................77 Conduits and Springs .........................................................................................................................77 Karst Recharge....................................................................................................................................80 Karst Drainage Basins .......................................................................................................................81 Hydrogeologic Characterization ...............................................................................................................82 Area of the Karst Drainage Basin ....................................................................................................82 Allogenic Recharge and Conduit Carrying Capacity ....................................................................83 Matrix and Fracture System Hydraulic Conductivity ....................................................................83 -

Physical Characteristics SPRING RIVER LAKE TI0 SD, Hancock Co

SPRING RIVER LAKE along with an occasional large fish. A small spring TI0 SD, Hancock Co. brook at the lake's western end contains modest U.S.G.S. Tunk Lake, ME (7 1/2') numbers of juvenile brook trout. This water is very popular with bait fishermen Fishes who trap many lively common shiners, a favored bait with ice anglers. Anglers should exercise extreme Landlocked salmon Minnows(con't) caution in guarding against an accidental Brown trout Fallfish(chub) introduction of any additional species which could Brook trout White sucker seriously jeopardize the fishery here and at Tunk Rainbow smelt Banded killifish Lake. Mionnows Threespine stickleback Golden shiner Redbreast sunfish Surveyed- July, 1952 Common shiner American eel (Revised- 1969, 1985, 1995) Alewife Maine Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife Funded in part by the Federal Aid in Restoration Act Physical Characteristics under Federal Project F-28-P L 4432 C Area- 704 acres Temperatures Surface- 75°F Maximum depth- 2B feet 2B feet- 6BoF Principal Fishery: Brown trout, salmon Spring River Lake is lc~a~~c~~=~h ~f Rc~te ° IB2 in TI0 SD. Small boats and canoes can be launched at a public area at the lake's southern end. Boats must be carried a short distance from the parking area to the shore. The lake provides marginal habitat for brown trout. However, during periods of hot weather, bottom temperatures become stressful and probably limit growth. Salmon were stocked periodically throughout the 1970's-BO's, but failed to provide a consistent fishery. The salmon stocking program was terminated in 1990. -

Hot Spring Pre-D Instr

Congratulations on your decision to enjoy the finest spa available... Welcome to the growing family of Hot Spring® Spa owners. Pre-Delivery Instructions lease take the time to read this booklet carefully, as it will provide you with the information you will need to Pensure the safe, secure, and timely installation of your new spa. The following sections are guidelines on how to prepare for delivery and set-up of your new spa. Specifically covered are site selection, delivery access, ground preparation, and electrical requirements. Remember to carefully read the Owner’s Manual that accompanies your spa, and to complete the warranty card within 10 days of delivery. These items, along with other valuable information, will be found in the Owner’s Package which has been placed in the equipment compartment of your spa, where you will also find its serial number. Watkins Manufacturing Corporation reserves the right to change features, specifications and design without notification and without incurring any obligation. DATE PURCHASED: __________________________________________________________________________ DATE INSTALLED:______________________________________________________________________________ DEALER:______________________________________________________________________________________ ADDRESS: ____________________________________________________________________________________ TELEPHONE:__________________________________________________________________________________ n most cities and counties, permits will be required for the installation of electrical circuits or the construction of Iexterior surfaces (decks and gazebos). In addition, some communities have adopted residential barrier codes which may require fencing and/or self-closing gates on the property to prevent unsupervised access to a pool (or spa) by children under 5 years of age. Your Hot Spring® Spa is equipped with a locking cover that meets the ASTM F1346-91 Standard for Safety Covers and as a result, is usually exempt from most barrier requirements.