New Perspectives in Corporate Law

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Etzionupdate from Yeshivat Har Etzion

בסד Summer 5777/2017 etzionUPDATE from Yeshivat Har Etzion Etzion Foundation Dinner 2017 On Wednesday March 29, hundreds of when Racheli delivered words of thanks The dinner culminated with dancing, friends gathered for the annual Etzion and chizuk. All the honorees appeared in bringing together all the members of the Foundation Dinner. The Foundation was a video presentation that also featured Gush community – Ramim and alumni, proud to present the Alumnus of the Year Roshei Yeshiva, Ramim, peers, children parents and children all rejoicing arm in award to Rabbi Jeffrey Kobrin ’92PC and and talmidim. The videos can be viewed at arm. Yair Hindin ‘98 commented, “It‘s this Michelle Greenberg-Kobrin. Simcha and http://haretzion.org/2017-honorees sense of community that always pulses Barbara Hochman, parents of Ayelet ’11MO through the Grand Hyatt during the Gush Rosh Yeshiva Rav Mosheh Lichtenstein and Ariel ’13, were honored with the dinner, this sense of the common bonds we spoke nostalgically and passionately of Parents of the Year award. all share, that keeps me coming back year the early days of his family’s aliyah and after year.” The Dor l’Dor Award was given to the state of the Yeshiva upon their arrival. Rav Danny Rhein his daughter, Describing the present, he noted the near Before the dinner, a reception was held Racheli (Rhein) Schmell ’07MO, whose impossibility of imagining not only the honoring the alumni of ’96 and ’97 on their combined warmth exponentially impacts current success of Gush but also the ever- 20th anniversary. In honor of the occasion, the tone and flavor of both Yeshivat Har growing presence that Migdal Oz has on the students from those years formed Etzion and Migdal Oz. -

Social Indicators in Corporate Activities Considering Sdgs - the Profit Maximization Criteria of Companies and Sdgs

1 Social Indicators in Corporate Activities considering SDGs - The Profit Maximization Criteria of companies and SDGs - Shigeo Uchida, Takako Hashimoto Chiba University of Commerce, Japan 1. Introduction The steady growth of the advanced countries began around 1820. The driving force was the rapid development of private companies, especially corporations. Establishment of a limited liability system for stockholders in advanced countries has greatly contributed to the evolution of companies. They were able to raise huge amount of money from ordinary citizens through limited liability system. Companies are profit making organizations that aim to maximize profits under the law. They have been leading technological and managing innovation to achieve the economic growth. However, prioritizing pursuing profits, companies have caused serious social problems such as pollution and environmental hazards. Many developed societies have emphasized on the Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR). Then they have established various laws and regulations such as the antitrust laws. At the beginning this century, in addition to legal regulations, many global institutions have formulated various guidelines for companies. The SDGs (the Sustainable Development Goals) agreed by all member countries of the United Nations in 2015 may be the most important fruit in present society. In financial and capital markets, ESG (Environment, Social, and Governance) investments are attracting attention. Companies seem to fulfill their responsibilities. However, the scandals of many large companies continue. Is it possible to make companies behaviors change? In this paper, we propose to use the tax system to incorporate the CSR concept into the profit maximization criteria of companies. 1. Companies brought economic growth and social problems It becomes a consensus of economist that private companies have brought innovation and economic growth through free market competition. -

Vol. 42, No. 3: Full Issue

Denver Journal of International Law & Policy Volume 42 Number 3 Summer Article 10 46th Annual Sutton Colloquium April 2020 Vol. 42, no. 3: Full Issue Denver Journal International Law & Policy Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/djilp Recommended Citation 42 Denv. J. Int'l L. & Pol'y (2014). This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Denver Sturm College of Law at Digital Commons @ DU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Denver Journal of International Law & Policy by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ DU. For more information, please contact [email protected],dig- [email protected]. Denver Journal _ of International Law and Policy VOLUME 42 NUMBER 3 SUMMER-2014 TABLE OF CONTENTS 46TH ANNUAL LEONARD v.B. SUTTON COLLOQUIUM: INTERNATIONAL LEGAL PERSPECTIVES ON THE FUTURE OF DEVELOPMENT KEYNOTE: WHAT DOES INTERNATIONAL LAW HAVE To Do WITH INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT? . David P. Stewart 321 THE FUTURE OF HUMAN DEVELOPMENT: THE RIGHT TO SURVIVE AS A FUNDAMENTAL ELEMENT OF THE RIGHT TO DEVELOPMENT ............... UpendraAcharya 345 HUMAN RIGHTS TAKE A BACK SEAT: THE SUPREME COURT HANDS OUT A PASS TO MULTINATIONALS AND OTHER WOULD BE VIOLATORS OF THE LAW OF NATIONS ................... W. Chadwick Austin 373 and Amer Mahmud INVESTING IN SUSTAINABILITY: ETHICS GUIDELINES AND THE NORWEGIAN SOVEREIGN WEALTH FUND...... Dr. Anita M. Halvorssen 389 and Cody D. Eldredge KEYNOTE: THE RIGHTS OF THE UNDERCLASS IN 2015 ..................... Peter Weiss 417 CAN THE CHINESE BIOGAS EXPERIENCE SHED LIGHT ON THE FUTURE OF SUSTAINABLE ENERGY DEVELOPMENT?.. Jason B. Aamodt 427 and Dr. -

Macroeconomic Dynamics at the Cowles Commission from the 1930S to the 1950S

MACROECONOMIC DYNAMICS AT THE COWLES COMMISSION FROM THE 1930S TO THE 1950S By Robert W. Dimand May 2019 COWLES FOUNDATION DISCUSSION PAPER NO. 2195 COWLES FOUNDATION FOR RESEARCH IN ECONOMICS YALE UNIVERSITY Box 208281 New Haven, Connecticut 06520-8281 http://cowles.yale.edu/ Macroeconomic Dynamics at the Cowles Commission from the 1930s to the 1950s Robert W. Dimand Department of Economics Brock University 1812 Sir Isaac Brock Way St. Catharines, Ontario L2S 3A1 Canada Telephone: 1-905-688-5550 x. 3125 Fax: 1-905-688-6388 E-mail: [email protected] Keywords: macroeconomic dynamics, Cowles Commission, business cycles, Lawrence R. Klein, Tjalling C. Koopmans Abstract: This paper explores the development of dynamic modelling of macroeconomic fluctuations at the Cowles Commission from Roos, Dynamic Economics (Cowles Monograph No. 1, 1934) and Davis, Analysis of Economic Time Series (Cowles Monograph No. 6, 1941) to Koopmans, ed., Statistical Inference in Dynamic Economic Models (Cowles Monograph No. 10, 1950) and Klein’s Economic Fluctuations in the United States, 1921-1941 (Cowles Monograph No. 11, 1950), emphasizing the emergence of a distinctive Cowles Commission approach to structural modelling of macroeconomic fluctuations influenced by Cowles Commission work on structural estimation of simulation equations models, as advanced by Haavelmo (“A Probability Approach to Econometrics,” Cowles Commission Paper No. 4, 1944) and in Cowles Monographs Nos. 10 and 14. This paper is part of a larger project, a history of the Cowles Commission and Foundation commissioned by the Cowles Foundation for Research in Economics at Yale University. Presented at the Association Charles Gide workshop “Macroeconomics: Dynamic Histories. When Statics is no longer Enough,” Colmar, May 16-19, 2019. -

Jerusalem (ARIJ) P.O Box 860, Caritas Street – Bethlehem, Phone: (+972) 2 2741889, Fax: (+972) 2 2776966

Applied Research Institute - Jerusalem (ARIJ) P.O Box 860, Caritas Street – Bethlehem, Phone: (+972) 2 2741889, Fax: (+972) 2 2776966. [email protected] | http://www.arij.org Applied Research Institute – Jerusalem Advocating for a Sustainable and Viable Resolution of Israeli-Palestinian Conflict “Israeli settlement Activities in the occupied State of Palestine” Volume 23, November 2018 Issue http://www.arij.org Brutality of the Israeli Occupation Army • The Israeli Occupation Army (IOA) invaded the al-Qar’aan neighborhood, in Qalqilia city, in northern West Bank, and searched a few homes. (IMEMC 1 November 2018) • In Nablus, in northern West Bank, the Israeli Occupation Army (IOA) invaded Ras al-Ein neighborhood, after surrounding it. (IMEMC 1 November 2018) • The Israeli Occupation Army (IOA) invaded Qabatia town, southwest of Jenin, searched the home of Jamal Hanaisha, and illegally confiscated 32.000 Shekels (approximately 8.630 Dollars) from the family. (IMEMC 1 November 2018) • The Israeli Occupation Army (IOA) invaded the home of Jamal Hanaisha, from Wad an-Naqqar area, in the northern West Bank city of Qalqilia, and violently searched it, before illegally confiscating 1.650 Shekels (approximately 445 Dollars). (IMEMC 1 November 2018) 1 Applied Research Institute - Jerusalem (ARIJ) P.O Box 860, Caritas Street – Bethlehem, Phone: (+972) 2 2741889, Fax: (+972) 2 2776966. [email protected] | http://www.arij.org • A number of Palestinians and international peace activists were injured by Israeli occupation Army (IOA) during the weekly anti-settlement march in the village of Kafr Qaddoum, in the northern occupied West Bank Governorate of Qalqilia. The IOA raided the village and attacked protesters with live bullets, rubber-coated steel bullets and tear-gas bombs. -

Asset Bubbles, Endogenous Growth, and Financial Frictions∗

Asset Bubbles, Endogenous Growth, and Financial Frictions∗ Tomohiro Hiranoyand Noriyuki Yanagawaz First Version, July 2010 This Version, October 2016 Abstract This paper analyzes the existence and the effects of bubbles in an endoge- nous growth model with financial frictions and heterogeneous investments. Bubbles are likely to emerge when the degree of pledgeability is in the mid- dle range, implying that improving the financial market might increase the potential for asset bubbles. Moreover, when the degree of pledgeability is rel- atively low, bubbles boost long-run growth; when it is relatively high, bubbles lower growth. Furthermore, we examine the effects of a bubble burst, and show that the effects depend on the degree of pledgeability, i.e., the quality of the financial system. Finally, we conduct a full welfare analysis of asset bubbles. Key words: Asset Bubbles, Endogenous Growth, Pledgeability, bubble burst, welfare effects of bubbles ∗This paper is a revised version of the our working paper, Hirano, Tomohiro, and Noriyuki Yanagawa. 2010 July. "Asset Bubbles, Endogenous Growth, and Financial Frictions," Working Paper, CARF-F-223, The University of Tokyo. We highly appreciate valuable comments from Francesco Caselli and four anonymous referees throughout revisions. We also thank helpful com- ments from Jean Tirole, Jose Scheinkman, Joseph Stiglitz, Kiminori Matsuyama, Fumio Hayashi, Katsuhito Iwai, Michihiro Kandori, Hitoshi Matsushima, Albert Martin, Jaume Ventura, and sem- inar participants at Econometric Society Word Congress 2010. We thank Shunsuke Hori and Jun Aoyagi for their excellent research assistance. Tomohiro Hirano acknowledges the financial sup- port from JSPS KAKENHI Grant No. 25220502, No. 15K17018, and No. 15KK0077. -

Civic Identity in the Jewish State and the Changing Landscape of Israeli Constitutionalism

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont CMC Senior Theses CMC Student Scholarship 2018 Shifting Priorities? Civic Identity in the Jewish State and the Changing Landscape of Israeli Constitutionalism Mohamad Batal Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.claremont.edu/cmc_theses Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, and the Law and Politics Commons Recommended Citation Batal, Mohamad, "Shifting Priorities? Civic Identity in the Jewish State and the Changing Landscape of Israeli Constitutionalism" (2018). CMC Senior Theses. 1826. https://scholarship.claremont.edu/cmc_theses/1826 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you by Scholarship@Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in this collection by an authorized administrator. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Claremont McKenna College Shifting Priorities? Civic Identity in the Jewish State and the Changing Landscape of Israeli Constitutionalism Submitted To Professor George Thomas by Mohamad Batal for Senior Thesis Spring 2018 April 23, 2018 ii iii iv Abstract: This thesis begins with an explanation of Israel’s foundational constitutional tension—namely, that its identity as a Jewish State often conflicts with liberal- democratic principles to which it is also committed. From here, I attempt to sketch the evolution of the state’s constitutional principles, pointing to Chief Justice Barak’s “constitutional revolution” as a critical juncture where the aforementioned theoretical tension manifested in practice, resulting in what I call illiberal or undemocratic “moments.” More profoundly, by introducing Israel’s constitutional tension into the public sphere, the Barak Court’s jurisprudence forced all of the Israeli polity to confront it. My next chapter utilizes the framework of a bill currently making its way through the Knesset—Basic Law: Israel as the Nation-State of the Jewish People—in order to draw out the past and future of Israeli civic identity. -

Fiduciary Duty, Human Rights, and the Corporate Decision Maker

Fordham Journal of Corporate & Financial Law Volume 26 Issue 1 Article 3 2021 Humanity Constrains Loyalty: Fiduciary Duty, Human Rights, and the Corporate Decision Maker Malcolm Rogge University of Exeter Law School, United Kingdom Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/jcfl Part of the Agency Commons, Business Administration, Management, and Operations Commons, Business Law, Public Responsibility, and Ethics Commons, and the Human Rights Law Commons Recommended Citation Malcolm Rogge, Humanity Constrains Loyalty: Fiduciary Duty, Human Rights, and the Corporate Decision Maker, 26 Fordham J. Corp. & Fin. L. 147 (2021). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fordham Journal of Corporate & Financial Law by an authorized editor of FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HUMANITY CONSTRAINS LOYALTY: FIDUCIARY DUTY, HUMAN RIGHTS, AND THE CORPORATE DECISION MAKER Malcolm Rogge* ABSTRACT This article considers whether the values contained within the idea of human rights have normative priority over economic values as they are inscribed in shareholder-oriented interpretations of the duty of loyalty in corporate law. While stakeholder theorists have sought to expand the ambit of the fiduciary duty—arguing generally that corporate fiduciary law permits managers to take into account a broad range of stakeholder interests—this article shifts the frame of analysis: It proposes that the range of corporate fiduciary loyalty is constrained by human rights as normative values that are distinct from the strictly economic values that are given primacy in the shareholder-centered approach. -

YEHONATAN KAPACH, Plaintiff Pro Se ADDRESS

1 YEHONATAN KAPACH, Plaintiff pro se 2 ADDRESS: 18375 Ventura Blvd, Suite 341, Tarzana, CA 91356 3 TEL: 818-571-6460, E-mail: [email protected] 4 5 6 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT 7 CENTRAL DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA YEHONATAN KAPACH, CASE NUMBER: Plaintiff, against COMPLAINT INTEL CORPORATION, DIKLA KLEIN YONA, YEHORAM SHAKED, ESTHER HAUT, DAPHNA BARAK EREZ, ANAT BARON, YAEL VILNER, EDNA ARBEL, DAVID MINTZ and GEORGE KARA. Defendants, 8 9 Plaintiff, pro se, for his complaint, alleges and sets forth as follows: 10 1. This is a complaint by an employee of Defendant Intel Corporation ("Intel") and several 11 public officials in the State of Israel, who have reduced the Plaintiff into a slave, extracting labor 12 from him for a period of 4 months without compensation. 13 14 2. Plaintiff's entire salary was transferred by Defendant Intel to the State of Israel by an order 15 of Defendant Dikla Klein Yona to satisfy a phantom debt for fictitious and stale child support that 16 was wholly paid years ago, leaving with no money Plaintiff and his new wife and two new children 17 as well as the daughter from the first marriage who moved to his custody in January 2013. 18 19 3. The enslavement of Plaintiff became possible against a background of a 20 poisonous radical feminist ideology that prevails in the State of Israel, and is promoted and 21 enforced by the co-Defendants named in the caption, who are judges in Israel that make it 22 impossible for a man to evet win a family case in that country, and it has led to countless events of 23 suicide (about 320 per years), impoverishment, denial of basic human rights, denial of due process 24 and fair trial, and in this case rendering men into slaves by robbing them of their ability to survive, 25 and/or a minimum modicum of living. -

Great Thinkers in Economics Series Series Editor: A.P

Great Thinkers in Economics Series Series Editor: A.P. Thirlwall is Professor of Applied Economics, University of Kent, UK. Great Thinkers in Economics is designed to illuminate the economics of some of the great historical and contemporary economists by exploring the interac- tions between their lives and work, and the events surrounding them. The books are brief and written in a style that makes them not only of interest to professional economists, but also intelligible for students of economics and the interested layperson. Forthcoming titles: David Reisman JAMES BUCHANAN David Cowan FRANK H. KNIGHT Peter Boettke F.A. HAYEK Titles include : Robert Scott KENNETH BOULDING Robert W. Dimand JAMES TOBIN Peter E. Earl and Bruce Littleboy G.L.S. SHACKLE Barbara Ingham and Paul Mosley SIR ARTHUR LEWIS John E. King DAVID RICARDO Esben Sloth Anderson JOSEPH A. SCHUMPETER James Ronald Stanfield and Jacqueline Bloom Stanfield JOHN KENNETH GALBRAITH Gavin Kennedy ADAM SMITH Julio Lopez and Michaël Assous MICHAL KALECKI G.C. Harcourt and Prue Kerr JOAN ROBINSON Alessandro Roncaglia PIERO SRAFFA Paul Davidson JOHN MAYNARD KEYNES John E. King NICHOLAS KALDOR Gordon Fletcher DENNIS ROBERTSON Michael Szenberg and Lall Ramrattan FRANCO MODIGLIANI William J. Barber GUNNAR MYRDAL Peter D. Groenewegen ALFRED MARSHALL Great Thinkers in Economics Series Standing Order ISBN 978–14039–8555–2 (Hardback) 978–14039–8556–9 (Paperback) (Outside North America only ) You can receive future titles in this series as they are published by placing a standing order. Please contact your bookseller or, in case of difficulty, write to us at the address below with your name and address, the title of the series and one of the ISBNs quoted above. -

FSA Institute Discussion Paper Series

FFSSAA IInnssttiittuuttee DDiissccuussssiioonn PPaappeerr SSeerriieess Asset Bubbles, Endogenous Growth, and Financial Frictions Tomohiro Hirano and Noriyuki Yanagawa DP 2010-1 March, 2011 Financial Research Center (FSA Institute) Financial Services Agency Government of Japan 3-2-1 Kasumigaseki, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo 100-8967, Japan You can download this and other papers at the FSA Institute’s Web site: http://www.fsa.go.jp/frtc/english/index.html Do not reprint or reproduce without permission. The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Financial Services Agency or the FSA Institute. FSA Institute Discussion Papers DP2010-1 (March, 2011) Asset Bubbles, Endogenous Growth, and Financial Frictions Tomohiro Hiranoyand Noriyuki Yanagawaz First Version, July 2010 This Version, March 2011 Abstract This paper analyzes the existence and the e¤ects of bubbles in an endogenous growth model with …nancial frictions and heterogeneous investments. Bubbles are likely to emerge when the degree of pledge- ability is in the middle range. This suggests that improving the …- nancial market might enhance the possibility of bubbles. We also …nd that when the degree of pledgeability is relatively low, bubbles boost long-run growth. When it is relatively high, bubbles lower growth. Moreover, we examine the e¤ects of bubbles bursting, and show that the e¤ects depend on the degree of pledgeability, i.e., the quality of the …nancial system. Key words: Asset Bubbles, Endogenous Growth, and Financial Frictions JEL code: E44, O43 We thank Kosuke Aoki, Toni Braun, Julen Esteban-Pretel, Fumio Hayashi, Masaru Inaba, Katsuhito Iwai, Masahito Kobayashi, Ryutaro Komiya, Kiminori Matsuyama, Masaya Sakuragawa, Kazuo Ueda, Jaume Ventura, and seminar participants at Bank of Japan, Econometric Society Word Congress 2010. -

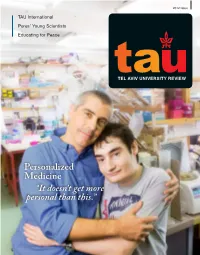

Personalized Medicine “It Doesn't Get More Personal Than This.”

2012 Issue TAU International Peres’ Young Scientists Educating for Peace TEL AVIV UNIVERSITY REVIEW Personalized Medicine “It doesn’t get more personal than this.” Cultural Immersion 14 The Marc Rich Program in the Humanities and the Arts is leading the way in revitalizing interest in the liberal arts. Cover story: Up Close and Personal 2 Rethinking Prof. Miguel Weil and his son, Nir, Addiction 16 are courageous poster boys for Tel Aviv University the promise – and frustrations – scientists are of genomic research at Tel Aviv researching new University. therapies for the treatment of addiction and pain. 3D Frontiers 22 Advanced 3D Technology being pioneered at TAU has implications for TEL AVIV UNIVERSITY REVIEW everything from security to surgery. 2012 Issue sections Issued by the Strategic Communications Dept. Development and Public Affairs Division innovations 22 Tel Aviv University Ramat Aviv 69978 Tel Aviv, Israel leadership 25 Tel: +972 3 6408249 From England Fax: + 972 3 6407080 E-mail: [email protected] with Love 28 The inaugural UK Legacy Mission initiatives 26 www.tau.ac.il brought a new group of British Jews into the TAU family. Editor: Louise Shalev Contributors: Rava Eleasari, Judd Yadid, associations 30 Sarah Lubelski, Bari Elias, Ilana Teitelbaum Graphic Design: TAU Graphic Design Studio/ Michal Semo-Kovetz digest 35 Photography: Development and Public Affairs Division Photography Department/Michal Roche Ben Ami, Michal Kidron newsmakers Additional Photography: Yoram Reshef; Rafael 38 Herlich; Isaac Harari, Knesset Media and Relations Division; Roee Ivgy; Jackie Simmonds; Adam Ha’Israeli; Avi Hayun; The Wiener Collection, Courtesy books 40 of Beit Hatfutsot Photo Archive Administrative Assistant: Roy Polad Printing: Eli Meir Printing Officers of Tel Aviv University a Harvey M.