Critical Access and Rural Hospitals in West Virginia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Morgantown 2015 EEO Public File Report

WEST VIRGINIA RADIO CORPORATION EEO PUBLIC FILE REPORT JUNE 2014- MAY 2015 for stations WVAQ and WAJR A. Full-Time Vacancies Filled During Past Year 1. Job Title: Digital Sales Representatives Date Filled: 7/28/14 and 8/4/14 (Hired 2) 2. Job Title: News Reporter Date Filled: 10/29/14 3. Job Title: Air Talent, WVAQ Date Filled: 2/23/15 4. Job Title: Copy Witer Date Filled: 3/2/15 and 3/16/15 5. Job Title: Account Executive Date Filled: 3/30/15 6. Job Title: Sports Video Journalist Date Filled: 4/10/15 B. Recruitment/Referral Sources Used to Seek Candidates for Each Vacancy 1. Job Title: Digital Sales Representatives Date Filled: 7/28/14 and 8/4/14 Source Contact Person Address Telephone # Interviewed Referred Person Hired Word of Mouth from current employees Internal Posting Jodi Hart 1251 Earl Core Rd., Morgantown 304-296-0029 1 1 Dominion Post Classifieds 1251 Earl Core Rd., Morgantown 304-292-6301 1 1 WVAQ & WAJR Facebook Pages Bill Vernon 1251 Earl Core Rd., Morgantown online posting 1 WAJR Website Patrick Rinehart www.wajr.com 304-296-0029 2. Job Title: News Reporter Date Filled: 10/29/14 Source Contact Person Address Telephone # Interviewed Referred Person Hired Internal Posting Jodi Hart 1251 Earl Core Rd., Morgantown 304-296-0029 Dominion Post Classifieds 1251 Earl Core Rd., Morgantown 304-292-6301 WV Broadcasters Assoc Michele Crist www.wvba.com All Access online www.allaccess.com On-air ads on WAJR Gary Mertins 1251 Earl Core Rd., Morgantown 304-296-0029 Word of Mouth from current employees 1 1 3. -

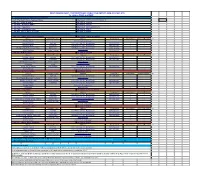

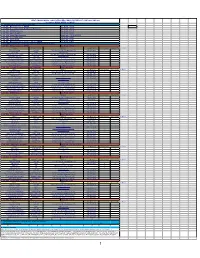

January 6, 2017 **Plans in CAWV Physical Plan Room (^) Paper (+) Disc Or Digital # CAWV Listed As Plan Holder

Newsletter 2017-01 January 06, 2017 LEGISLATIVE INTERIMS NEXT WEEK; SESSION BEGINS THEN RECESSES The 2017 legislative session will start 30 days late this year to give Governor-elect Jim Justice time to develop his legislative agenda. The session will begin February 8 but lawmakers will be in town next week for legislative interim meetings and to elect House and Senate leadership. One of the items for discussion will be the development of the proposed Rock Creek Development Park on the 12,000 acre Hobet mine site in Boone County. The project is needed to create economic opportunity in southern West Virginia, Governor Earl Ray Tomblin notes. Legislators have questioned spending $58 million for grading and draining 2.6 miles of road to access the site off of Corridor G when the WVDOH is struggling to maintain the state’s road and bridge system. A number of other construction related issues will be on the interim schedule, which will be Monday, Tuesday and Wednesday at the Capitol. A full recap of the interim meetings will be in next week’s Newsletter. CAWV MEMBER TAPPED FOR COMMERCE SECRETARY; PAUL MATTOX, DAVID SNEED DEPARTURES Woody Thrasher, president of The Thrasher Group, an engineering and architecture firm headquartered in Bridgeport, was named new Commerce Secretary by Governor-elect Justice. “Woody shares my vision that what we need is a better marketing and economic opportunity surrounded by jobs, jobs, jobs for the people of West Virginia,” said the new governor of his appointee. “He's been on my mind for commerce secretary for a while because he understands what it takes to diversify West Virginia's economy.” Thrasher, who’s company has offices in West Virginia, Ohio, Maryland and Virginia, said, “I'm really excited to have the opportunity to work with Governor-elect Justice. -

August 17, 2018

Newsletter 2018-33 August 17, 2018 DELEGATES ADVANCE IMPEACHMENT ARTICLES AGAINST FOUR WEST VIRGINIA JUSTICES The House of Delegates named Chief Justice Margaret Workman, Justice Beth Walker, suspended Justice Allen Loughry and now retired Justice Robin Davis in a total of 11 Articles of Impeachment following votes Monday and early Tuesday. Davis will avoid a trial in the Senate after handing in her retirement to Gov. Jim Justice Monday night. She announced it Tuesday morning. State Senate President Mitch Carmichael plans to call members of the Senate back to Charleston next Monday to adopt the rules that will be followed during impeachment trials involving three state Supreme Court justices. If the Senate votes to remove justices from office, Gov. Jim Justice would fill the vacancies through appointment with the guidance of the state Judicial Vacancies Commission. The commission released the following recommendations this week. • Robert H. Carlton, Williamson • Evan Jenkins, Huntington • Gregory B. Chiartas, Charleston • Robert J. Frank, Lewisburg • Evan Jenkins, Huntington • Arthur Wayne King, Clay • D.C. Offutt Jr., Barboursville • William Schwartz, Charleston • Martin P. Sheehan, Wheeling OSHA POST NEW LIST OF FAQs ON THE SILICA RULE The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) has just released a set of 53 Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) to provide guidance to employers and employees regarding OSHA’s respirable crystalline silica standard for construction. The FAQs were developed in conjunction with the Associated General Contractors of America (AGC) and the American Road & Transportation Builders Association (ARTBA) through the Construction Industry Safety Coalition (CISC). The development of the FAQs stem from litigation filed against OSHA by numerous construction industry associations challenging the legality of OSHA’s rule. -

WEST VIRGINIA RADIO CORPORATION EEO PUBLIC FILE REPORT JUNE 2018- MAY 2019 for Stations WVAQ, WKKW and WAJR A

WEST VIRGINIA RADIO CORPORATION EEO PUBLIC FILE REPORT JUNE 2018- MAY 2019 for stations WVAQ, WKKW and WAJR A. Full-Time Vacancies Filled During Past Year 1. Job Title: Midday Announcer, WKKW Date Filled: 6/11/18 2. Job Title: Account Executive, Multimedia / Metronews Date Filled: 8/2/18 3. Job Title: WKKW Announcer Date Filled: 8/13/18 4. Job Title: Sports Reporter Date Filled: 8/9/18 5. Job Title: Digital Sales Specialist Date Filled: 7/30/18 & 9/10/18 6. Job Title: Account Executive Date Filled: 9/4/18 7. Job Title: Sports Writer Date Filled: 9/7/18 8. Job Title: Midday Announcer / Program Director, WKKW Date Filled: 3/25/19 B. Recruitment/Referral Sources Used to Seek Candidates for Each Vacancy 1. Job Title: Midday Announcer, WKKW Date Filled: 6/11/18 Source Contact Person Address Telephone # Interviewed Referred Person Hired Internal Posting Jodi Hart 1251 Earl Core Rd., Morgantown, WV 304-296-0029 1 1 All Access onine allaccess.com WKKW Facebook Posting Patrick Rinehart 1251 Earl Core Road, Morgantown, WV 304-296-0029 WV Radio Web site Jodi Hart www.wvradio.com 304-296-0029 **WV Div of Rehabilitation Linda Lutman 1415 Earl Core Road, Morgantown WV 304-285-3155 **American Broadcasting School Michelle McDonnell 4511 SE 29th Street, Oklahoma City, OK 405-672-6511 **Fairmont State University Meagan Gibson 1201 Locust Ave, Fairmont WV 304-333-3665 **Ohio Media School Alvis Moore 5330 East Main Street, Columbus OH 614-655-5250 2. Job Title: Account Executive, Multimedia / Metronews Date Filled: 8/2/18 Source Contact Person Address Telephone # Interviewed Referred Person Hired Internal Posting Jodi Hart 1251 Earl Core Rd., Morgantown, WV 304-296-0029 1 1 WV Broadcasters Assoc Michele Crist PO Box 8499, S. -

Erin E. Magee

Erin E. Magee Of Counsel Charleston Office 500 Lee Street East Pittsburgh Office Suite 1600 501 Grant Street Charleston, WV 25301 Suite 1010 (O): 304.340.1360 Pittsburgh, PA 15219 (F): 304.340.1130 (C): 304.539.8360 [email protected] Erin E. Magee is Of Counsel in the Energy and Manufacturing industry groups, focusing primarily on labor and employment matters. She practices out of the Firm’s offices in Charleston, West Virginia, and Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. One of Erin’s best qualities is her straightforward, no-nonsense approach – she won’t tell you what you want to hear, but rather what you need to hear. This is what every client should seek out in an attorney. Erin is passionate about helping clients navigate issues in the workplace, consulting daily with employers about wage and hour issues, employee leave and benefit questions, reductions in force, drug testing, workplace privacy, personnel policies, and employee discharge and discipline issues. Erin also provides training and speaks at seminars and conferences on issues such as how to avoid harassment in the workplace. She is knowledgeable on this subject because she regularly conducts investigations of complaints of harassment and discrimination in the workplace. She knows providing guidance and advice on the front end often prevents the issues that ultimately lead to litigation. Erin has built a solid labor and employment practice because she’s more than just a litigator – she’s an advisor, an instructor, and a fierce advocate. Her investigation and advisory skills are built upon two decades of success litigating on behalf of employers in state and federal courts, as well as before the West Virginia Human Rights Commission, the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC), the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB), and in mediation and arbitration. -

WV Emergency Alert System Plan

WEST VIRGINIA EMERGENCY ALERT SYSTEM OPERATIONAL PLAN REVISED MARCH 2011 West Virginia Emergency Alert System Operational Plan Revised August 2010 STATE OF WEST VIRGINIA Emergency Alert System Operational Plan This plan was prepared by the West Virginia State Emergency Communications Committee in cooperation with the West Virginia Broadcasters Association, the West Virginia Division of Homeland Security and Emergency Management Services; the National Weather Service - West Virginia;; the West Virginia chapter of the Society of Broadcast Engineers; West Virginia chapter of the Society of Cable Telecommunication Engineers; State and local officials; and the broadcasters and cable systems of West Virginia. Page 2 West Virginia Emergency Alert System Operational Plan Revised August 2010 Page 3 West Virginia Emergency Alert System Operational Plan Revised August 2010 Table of Contents Page Approvals and Concurrence 3 Intent and Purpose 5 General Considerations 5 National, State and Local EAS: Participation and Priorities 6 National Participation 6 State and Local Participation 6 Conditions of EAS Participation 6 EAS Priorities 7 Compliance 7 West Virginia State Emergency Communications Committee (WVSECC) 7 Organization and Concepts of the West Virginia Emergency Alert System 8 EAS Designations 8 Other Designations 8 Definitions 9 General Procedures for use by Broadcast Stations and Cable Systems 11 Communications between WVDHSEM, NWS, Industrial Plants and Cable 12 Testing the Emergency Alert System 12 Required Weekly Test (RWT) 12 Required -

UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT Southern District of West Virginia

Case 2:20-bk-20007 Doc 311 Filed 03/01/20 Entered 03/02/20 00:36:36 Desc Imaged Certificate of Notice Page 1 of 40 Form ntcempro UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT Southern District of West Virginia In Thomas Health System, Inc. and Herbert Re: J. Thomas Memorial Hospital Association Case No.: 2:20−bk−20007 Debtor(s) Chapter: 11 Judge: Frank W. Volk USDJ NOTICE TO ALL PARTIES IN INTEREST OF MOTION/APPLICATION TO EMPLOY PROFESSIONAL The following document was filed: 302 − Application by Creditor Committee Official Committee of Unsecured Creditors to Employ Sills Cummis & Gross P.C as Attorneys for the Official Committee of Unsecured Creditors . (Attachments: # 1 Exhibit Retention Declaration (Muraya) # 2 Exhibit Retention Declaration (Sherman)) (Horter, Josef) The aforementioned pleading is on file in the office of the undersigned Clerk, and you may review the same during regular business hours of the Court, or at anytime via ECF or PACER. YOU ARE FURTHER NOTIFIED that if you object to the Motion/Application you must file your objection with the Clerk of this Court within 21 days from the date of this Notice stating the nature of the objection with specificity; any proper objection will be set for hearing upon further notice to the interested parties. The Court may elect to hold a hearing in the absence of any written response. Dated: 2/28/20 MATTHEW J. HAYES, CLERK Case 2:20-bk-20007 Doc 311 Filed 03/01/20 Entered 03/02/20 00:36:36 Desc Imaged Certificate of Notice Page 2 of 40 United States Bankruptcy Court Southern District of West Virginia In re: Case No. -

© 2021 Thomson Reuters. No Claim to Original U.S. Government Works. 1 United States V

United States v. Loughry, 983 F.3d 698 (2020) 983 F.3d 698 United States Court of Appeals, Fourth Circuit. UNITED STATES of America, Plaintiff - Appellee, v. Allen H. LOUGHRY II, Defendant - Appellant. No. 19-4137 | Argued: October 29, 2020 | Decided: December 21, 2020 Synopsis Background: After defendant, a justice of state's highest court, was convicted of mail fraud, seven counts of wire fraud, and two counts of making false statements to a federal agent, the United States District Court for the Southern District of West Virginia, John T. Copenhaver, Senior District Judge, denied, without an evidentiary hearing, defendant's motion for new trial based on juror misconduct and bias, and later, 2019 WL 177476, granted in part and denied in part defendant's second motion for judgment of acquittal or new trial. Defendant appealed. Holdings: The Court of Appeals, Niemeyer, Circuit Judge, held that: juror's conduct in following the microblog posts of journalists covering the trial did not warrant evidentiary hearing regarding juror's private contacts, and juror's voir dire responses regarding her pretrial knowledge of the case were not materially dishonest. Affirmed. Diaz, Circuit Judge, filed an opinion concurring in part and dissenting in part. Procedural Posture(s): Appellate Review; Post-Trial Hearing Motion. *700 Appeal from the United States District Court for the Southern District of West Virginia, at Charleston. John T. Copenhaver, Jr., Senior District Judge. (2:18-cr-00134-1) Attorneys and Law Firms ARGUED: Elbert Lin, HUNTON ANDREWS KURTH LLP, Richmond, Virginia, for Appellant. Richard Gregory McVey, OFFICE OF THE UNITED STATES ATTORNEY, Huntington, West Virginia, for Appellee. -

Sole Source Determination Template

SOLE SOURCE DETERMINATION The Purchasing Division has been requested to approve a sole source purchase for the commodity or service described below. Pursuant to West Virginia Code 5A-3-10c, the Purchasing Division is attempting to determine whether the commodity or service is a sole source procurement. If you believe your company meets the required experience and qualification criteria stated below, please e-mail the Purchasing Division Buyer at [email protected] with a copy to [email protected] to express your interest in the project. Please forward any and all information that will support your company’s compliance with required qualification and eligibility criteria along with any other pertinent information relative to this project to the Purchasing Division no later than 1:30 pm on 07/09/2010. Requisition Number: NCS08RCPG Department/Agency: WV Commission for National & Community Service Detailed Description of Project: The West Virginia Citizen Corps, a program of Volunteer West Virginia, has funding available to increase public preparedness for an emergency situation through the Regional Catastrophic Preparedness Grant Program (RCPGP). As one part of the overall project, Citizens Corps will deliver media messages intended to educate the public about general personal preparedness techniques, shelter-in-place, emergency communication procedures, and emergency evacuation strategies. By providing these messages statewide, individuals will be exposed to specific details of how to make their families more resilient during a catastrophic disaster. In addition, the messages produced will be made available throughout the REMA Region III states for distribution. The vendor, in conjunction with WV Radio Corporation and West Virginia Citizen Corps will deliver the following: - Creation, production, and distribution of at least four 30 second media messages. -

Document Title

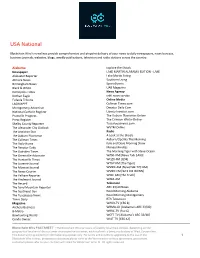

USA National Blockchain Wire’s newslines provide comprehensive and pinpoint delivery of your news to daily newspapers, news bureaus, business journals, websites, blogs, weekly publications, television and radio stations across the country. Alabama Explore the Shoals Newspaper LAKE MARTIN ALABAMA EDITION - LAKE Alabaster Reporter Lake Martin Living Atmore News Southern Living Birmingham News SportsEvents Black & White UAB Magazine Demopolis Times News Agency Dothan Eagle cnhi news service Eufaula Tribune Online Media LAGNIAPPE Cullman Times.com Montgomery Advertiser Decatur Daily.Com National Catholic Register Liberty Investor.com Prattville Progress The Auburn Plainsman Online Press-Register The Crimson White-Online Shelby County Reporter Tuscaloosanews.com The Alexander City Outlook WVTM Online The Anniston Star Radio The Auburn Plainsman A Look at the Shoals The Cullman Times Auburn/Opelika This Morning The Daily Home Kyle and Dave Morning Show The Decatur Daily Money Minutes The Gadsden Times The Morning Tiger with Steve Ocean The Greenville Advocate WANI-AM [News Talk 1400] The Huntsville Times WQZX-FM [Q94] The Luverne Journal WTGZ-FM [The Tiger] The Monroe Journal WVNN-AM [NewsTalk 770 AM] The News-Courier WVNN-FM [92.5 FM WVNN] The Pelham Reporter WXJC-AM [The Truth] The Piedmont Journal WZZA-AM The Record Television The Sand Mountain Reporter ABC 33/40 News The Southeast Sun Good Morning Alabama The Tuscaloosa News Good Morning Montgomery Times Daily RTA Television Magazine WAKA-TV [CBS 8] Archery Business WBMA-LD [Alabama's ABC 33/40] B-Metro WBRC-TV [Fox 6] Bowhunting World WCFT-TV [Alabama's ABC 33/40] Condo Owner WIAT-TV [CBS 42] Blockchain Wire FACTSHEET | The Blockchain Wire service is offered by local West entities, depending on the geographical location of the customer or prospective customer, each such entity being a subsidiary of West Corporation. -

History, Identity, and Narrative in the West Virginia Teacher Strikes of 2018 and 2019

“For Our Kids, For Our State”: History, Identity, and Narrative in the West Virginia Teacher Strikes of 2018 and 2019 Catherine H. G. Gooding Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Prerequisite for Honors in Anthropology under the advisement of Justin Armstrong April 2019 © 2019 Catherine Helena Grace Gooding For my teachers Acknowledgements This thesis is a year’s labor of love which was made possible only through the contributions of my communities at home in West Virginia and here at Wellesley College. To the following people, I am profoundly indebted to you. Thank you for supporting my vision. First and foremost, none of my research would have been possible without the generous contribution of Professor Emerita Andrea Levitt and the Samuel and Hilda Levitt Fellowship. Your gift offered me the freedom to pursue my passion, and for that I am deeply grateful. To my beautiful network of West Virginian Wellesley Sibs, thank you for welcoming me into your ranks with open arms. Thank you to Katelyn for showing me what it looks like to love West Virginia unapologetically, and thank you also to my West Virginia first-years Annabel, Katherine, and Britney, just literally for being here and being your bright, wonderful selves. We need you. It has been my great honor to serve as the Active Minds president for the last year and a half. Thank you to my e-board for your wonderful teamwork and commitment to the Wellesley Community, and to Robin, Jan, and Claudia for your mentorship and support. Thank you to everyone who has listened to me ramble about West Virginia for the past year, but thanks especially to Emma, Alyssa, Nhia, Briana, Alexei, Helene, Maya, and of course, my Wellesley Wife Hailey for putting up with me. -

14 West Virginia Radio Corporation Eeo Public File

WEST VIRGINIA RADIO CORPORATION EEO PUBLIC FILE REPORT JUNE 2012- MAY 2013 for stations WVAQ and WAJR A. Full-Time Vacancies Filled During Past Year 1. Job Title: Grounds Maintenance Date Filled: 5/14/13 hired w/o posting due to urgency of hire 2. Job Title: News Reporter/Director Date Filled: 4/2/13 3. Job Title: Accountant Date Filled: 11/19/12 4. Job Title: MetroNews Reporter Date Filled: 8/20/12 B. Recruitment/Referral Sources Used to Seek Candidates for Each Vacancy 1. Job Title: Grounds Maintenance Date Filled: 10/1/12 Source Contact Person Address Telephone # Interviewed Referred Person Hired memo attached 2. Job Title: News Reporter/Director Date Filled: 4/2/13 Source Contact Person Address Telephone # Interviewed Referred Person Hired On-Air Ads on WVAQ Gary Mertins 1251 Earl Core Rd., Morgantown 304-296-0029 On-Air Ads on WKKW Gary Mertins 1251 Earl Core Rd., Morgantown 304-296-0029 On-Air Ads on WAJR Gary Mertins 1251 Earl Core Rd., Morgantown 304-296-0029 Word of Mouth from current employees 1 Internal Posting Jodi Hart 1251 Earl Core Rd., Morgantown 304-296-0029 Dominion Post Classifieds 1251 Earl Core Rd., Morgantown 304-292-6301 WAJR Website Tim Loughry www.wajr.com 304-296-0029 Word of Mouth from current employees 1 1 Specs Howard School of Broadcasting Telephone Contact 248-358-9000 1 1 Ohio University [email protected] WVU School of Journalism http://sojenews.wvu.edu West Virginia Radio Broadcasters Assoc. www.wvba.com/job-bank All Access on line posting allaccess.com 6 TV & Radio Jobs.com http://tvandradiojobs.com 3.