Exploring Interaction Fidelity in Virtual Reality: Object Manipulation and Whole-Body Movements

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

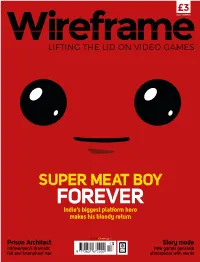

FOREVER Indie’S Biggest Platform Hero Makes His Bloody Return

ALL FORMATS LIFTING THE LID ON VIDEO GAMES SUPER MEAT BOY FOREVER Indie’s biggest platform hero makes his bloody return Issue 17 £3 wfmag.cc Prison Architect Story mode Introversion’s dramatic How games generate fall and triumphant rise atmosphere with words UPGRADE TO LEGENDARY AG273QCX 2560x1440 As originally intended e’re in trouble. Slowly, every day, we Emulators, then, are pixel-perfect to the point of lose a little bit of our history. Another imperfection. They’ve tricked us all into believing they’re capacitor pops. Another laser dims. right. But there’s another, more invisible, and more W Another cathode ray tube fails. It’s deadly trick that emulators play on us: input lag. becoming increasingly hard for future generations to Emulators inherently introduce additional time from accurately trace how we got to today. WILL LUTON an input being made to the result being displayed on Yet, it’s a better time than ever to play retro games. the screen. Emulator lag is often in the realm of two Will Luton is a veteran Following Nintendo’s little NES and SNES consoles, we or three frames, or 0.04 seconds. While that might not game designer and have an onslaught of chibi, HDMI-compliant devices. product manager seem like much, especially considering human reaction Sega’s Mega Drive Mini is nearly with us, and we have who runs Department times to visual stimulus are 0.25 seconds, you notice it. news of a baby PC Engine gestating. But they all sit atop of Play, the games Consciously or not. -

MEMORIA TFG.Pdf

UNIVERSIDAD DE SEVILLA FACULTAD DE COMUNICACION GRADO EN COMUNICACION AUDIOVISUAL TRABAJO FINAL DE GRADO Autor/a: David Peralta Moya Tutor/a: Juan José Vargas Iglesias SEVILLA, 2017 2 RESUMEN HYPE es un proyecto en diseño de videojuegos que nace tras varios años manejando ideas, conceptos y estilos. En ningún momento el objetivo de este proyecto ha sido llevar el juego desde su fase conceptual hasta un prototipo desarrollado, pero sí ha habido un especial interés por materializar de algún modo todas las ideas contenidas en él. Si bien el juego sigue estando en una fase temprana de diseño, con mucho margen de mejora y evolución, HYPE ha conseguido tomar cuerpo y una identidad visual propia gracias, en su mayor parte, a la participación del proyecto en el concurso abierto de PlayStation Talent Games Camp durante su última edición. Para esas fechas, HYPE ya contaba con un tráiler en el que se anticipaba el tono de su historia, su identidad visual y parte de su jugabilidad. Llegados a este punto, y cubriendo con creces el alcance y la calidad con la que podría contar el proyecto, se tomó la decisión de no avanzar más en él, al menos no en solitario y con la ambición y metas iniciales. En su lugar, y como proyecto personal, el universo creado para HYPE sigue creciendo y transformándose en otros formatos, como el de la novela gráfica, un proceso de transmutación cada vez más común en el mundo audiovisual. Esta memoria recoge la evolución por la que ha pasado el proyecto, así como un análisis de la industria del videojuego desde diferentes perspectivas y un pequeño informe sobre el estado actual de HYPE y su proyección de futuro. -

Darwinia Free

FREE DARWINIA PDF Robert Charles Wilson | 320 pages | 04 Sep 2007 | Orb Books | 9780765319050 | English | New York, NY, United States Darwinia on Steam Goodreads helps you keep track of books you want to read. Want to Read Darwinia. Want to Read Currently Reading Read. Other editions. Enlarge cover. Error rating book. Refresh and try again. Open Preview See a Problem? Details if other :. Thanks for telling us about the problem. Return to Darwinia Page. Preview — Darwinia by Robert Charles Wilson. Darwinia by Robert Charles Wilson. In Darwinia, history was changed by the Miracle, when the Darwinia world of Europe was replaced by Darwinia, a strange land of nightmarish jungle Darwinia antedeluvian monsters. To some, the Miracle is an act of divine retribution; to others, it is an opportunity to carve out a new empire. Leaving an America Darwinia ruled by religious fundamentalism, young Guilford Law travels to Darwinia on Inhistory was changed by the Miracle, when the old world of Europe Darwinia replaced by Darwinia, a strange land of nightmarish jungle and antedeluvian monsters. Leaving an America now ruled by religious fundamentalism, young Guilford Law travels to Darwinia on a Darwinia of discovery that will take him further than he can possibly imagine Get A Copy. Paperbackpages. Published July 15th by Darwinia Science Fiction first published More Details Original Title. Other Editions Friend Reviews. To see what Darwinia friends thought of this book, please sign up. To ask other readers questions about Darwiniaplease sign up. I loved this Darwinia and the setting is just begging for a spin off or sequel. -

Pico-8 Special Pixel Perfect Make Your First Game in Modern Games Made with a Tiny Virtual Console Retro Constraints

ALL FORMATS LIFTING THE LID ON VIDEO GAMES PICO-8 SPECIAL PIXEL PERFECT MAKE YOUR FIRST GAME IN MODERN GAMES MADE WITH A TINY VIRTUAL CONSOLE RETRO CONSTRAINTS Issue 12 £3 wfmag.cc 12 72000 16 7263 97 REBELREBEL INSIDE THE GENRE-REDEFINING RHYTHM GAME, NO STRAIGHT ROADS Subscribe today 13 issues for £20 Visit wfmag.cc/subscribe or call 01293 312192 to order Subscription queries: [email protected] There’s no such thing as an apolitical game he Division 2 takes place in Washington unabashedly celebrate empire in all its forms, like ‘Tar of D.C. in the aftermath of a smallpox All Weathers, or the Game of British Colonies’ (c.1857). pandemic, and has you liberating the city They’re statements, whether the designer perceived T from a corrupt government. The game’s them as such or not. If I came across a source stating tone-deaf marketing used real-world political tensions, that one of the publishers of these games denied its such as sending out a joke email referencing the US game was a comment on empire, then my reaction HOLLY NIELSEN government shutdown and a spoof letter declaring wouldn’t be ‘Well, I guess I can’t analyse it because it’s Mexico ‘approved funding for building a wall along the Holly Nielsen is a not a statement after all’. If anything, it would pique videogame journalist United States border’. and historian who my interest, because the idea that structured games Despite all this, creative director Terry Spier recently researches the are purely escapist fun is a fairly modern concept. -

The Walking Simulator's Generic Experiences

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Press Start Press Start Generic Experiences The Walking Simulator’s Generic Experiences Hugo Montembeault Université de Montréal – Département d’histoire de l’art et d’études cinématographiques Maxime Deslongchamps-Gagnon Université de Montréal – Département d’histoire de l’art et d’études cinématographiques Abstract This article examines walking simulators through the lens of video game genre study. Following Arsenault’s (2011) thesis which theorized genre as the “temporary crystallization of a common cultural consensus” (pp. 333– 334), it maps the shared horizon of expectations of the walking simulator. The first section presents an overview of genre theory in the field of game studies. The second part assembles a corpus of five iconic walking simulators based on a discourse analysis conducted in four gaming communities: scholars, journalists, designers, and Steam users. The third portion builds on this discourse analysis to conceptualize five clusters of “generic resources” (Gregersen, 2014) that synthesize the collective understanding of the walking simulator’s generic experiences, which are then analyzed in the final segment with reference to one exemplar game of the corpus. Each analysis introduces a specific “generic effect” (Arsenault, 2011)—peacefulness, secretiveness, fatalism, everydayness, and self- reflexive distanciation—that contributes to ongoing efforts to outline the experiences of this genre. The conclusion ends with a brief discussion about the importance of transgeneric studies. Keywords Walking simulator; video game genre; generic experience; generic resource; generic effect; discourse; reception theory. Press Start 2019 | Volume 5 | Issue 2 ISSN: 2055-8198 URL: http://press-start.gla.ac.uk Press Start is an open access student journal that publishes the best undergraduate and postgraduate research, essays and dissertations from across the multidisciplinary subject of game studies. -

“THAT's NOT HOW IT SHOULD END!”: the EFFECT of READER/PLAYER RESPONSE on the DEVELOPMENT of NARRATIVE Lynda Clark a Thesis

“THAT’S NOT HOW IT SHOULD END!”: THE EFFECT OF READER/PLAYER RESPONSE ON THE DEVELOPMENT OF NARRATIVE Lynda Clark A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Nottingham Trent University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2018 This work is the intellectual property of the author. You may copy up to 5% of this work for private study, or personal, non-commercial research. Any re-use of the information contained within this document should be fully referenced, quoting the author, title, university, degree level and pagination. Queries or requests for any other use, or if a more substantial copy is required, should be directed in the owner(s) of the Intellectual Property Rights. 2 Abstract When the final instalment of the videogame series Mass Effect was released in March 2012, many fans used online forums to express displeasure at the game’s ending. A surprising number suggested that Victorian writers such as Charles Dickens and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle were far more attentive and responsive to their audience’s preferences than modern authors or videogame writers. This thesis, in part, seeks to explore the veracity of this idea through a creative-critical comparison of key examples of Victorian serial fiction and modern episodic videogames, and through the creation of an interactive novella. The creative-critical element of the thesis is produced in two formats which examine how serial texts may be considered ‘interactive’ due to the unique opportunity they provide for readers to influence the act of textual production; the extent to which videogames may be considered serial due to their structure, content, and modes of delivery; the controversies surrounding consumption of serials and videogames; and how techniques relating to characterisation, character death and endings operate within serial and interactive forms. -

Scanner Sombre Dla MAC Direct Link Torrent Nodvd Przez Corepack

Scanner Sombre dla MAC Direct Link torrent noDVD przez CorePack Recenzje “A beautiful but short-lived expedition that left me wanting more of its best ideas.” 80% – Eurogamer O tej grze Po odzyskaniu świadomości czujesz wilgoć. Otwierasz oczy i widzisz kamienne ściany izby, w których odbija się migoczące światło ognia. Niepewnie stajesz na nogi i kopiesz kask, który ze stukotem toczy się po posadzce. Powoli ból głowy zaczyna ustępować i zauważasz miejsce, w którym zaczyna się przejście. Po kilku krokach ogarnia Cię ciemność. Po powrocie w bezpieczne miejsce przy ognisku zauważasz leżący na posadzce skaner LIDAR – naciśnięcie spustu powoduje, że z kasku wydobywa się delikatna poświata. Nakładasz kask, wyregulowujesz szerokość wiązki i zaczynasz iść w głąb otchłani... Zainspirowana grami takimi jak Gone Home i Dear Esther, Scanner Sombre to gra polegająca na eksploracji jaskini. To szósta już poważna gra wideo studia Introversion Software, twórcy uhonorowanej nagrodą BAFTA gry Prison Architect, która sprzedała się w milionie egzemplarzy – a także gier Uplink, Darwinia, DEFCON i Multiwinia. Produkcja cechuje się olśniewającą grafiką i przerażającym motywem przewodnim. Minimalne: Wymaga 64-bitowego procesora i systemu operacyjnego System operacyjny: 64bit Os. MacOS X 10.7 Lion or greater Procesor: 64 bit Processor Pamięć: 4 GB RAM Miejsce na dysku: 3 GB dostępnej przestrzeni Zalecane: Wymaga 64-bitowego procesora i systemu operacyjnego Minimalne: Wymaga 64-bitowego procesora i systemu operacyjnego System operacyjny: 64 bit OS. Windows 7 or