La Trobe University, Faculty of Education (PDF 2631KB)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bachelor of Education (Inservice)

Bachelor of Education (Inservice) Handbook Domestic Entry requirements overall 6.5 Year 2014 Prerequisite Completion of a Diploma of Teaching (or Enrolling It is imperative that you enrol in both QUT code ED26 equivalent). semester 1 and semester 2 units at the Duration 1 year (full-time) start of each year when you commence in semester 1. Duration 2 years Teacher registration eligibility (part-time Please note that if you are not eligible for domestic) registration as a teacher with the Course Structure You are required to complete eight, 12 Campus Kelvin Grove Queensland College of Teachers (QCT) on entry to the course, completion of this credit point units of study. Domestic fee 2014: CSP $3,400 per course will not provide QCT eligibility. You (indicative) Study Period (48 credit The course provides flexibility for students points) should contact QCT for confirmation of your eligibility for registration before to complete their studies across a range International fee 2014: $12,400 per Study commencing the course. of areas. (indicative) Period (48 credit points) Two core units must be completed, Total credit 96 International Entry points EDP415 Engaging Diverse Learners and requirements EDP416 The Professional Practice of Start months February, July You must have completed a Diploma of Educators, along with an additional two Int. Start Months February, July Teaching (or equivalent). units from any of the courses offered by the Faculty of Education. The remaining Course Contact Education four units may be taken from a wide range Coordinator Student Affairs Section of Faculty of Education units in other 3138 3947, or [email protected] Faculty of Education courses including u For course progression Teacher Registration advice please contact Jo Bachelor of Education (Secondary), Wakefield on 07 3138 Eligibility Bachelor of Education (Primary), Bachelor 3948, or Please note that if you are not eligible for of Education (Early Childhood), Bachelor [email protected]. -

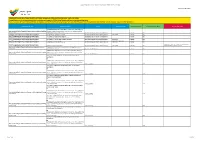

Approved Qualifications List for Educators Working with Over Preschool Age Children

Approved Qualifications for Educators Working with Children Over Preschool Age Updated: 15 May 2017 APPROVED QUALIFICATIONS FOR EDUCATORS WORKING WITH OVER PRESCHOOL AGE CHILDREN The qualifications on this list have been published in accordance with regulation 137(2)(c) of the Education and Care Services National Regulations. There is no national list of prescribed qualifications for educators working with children over preschool age. Each state and territory determines the qualification requirements for 'over preschool age' educators in their jurisdictions. Awarding Institution Qualification Name Position Qualification Code Awarding Country Jurisdiction where applies Notes (if applicable) Completed the equivalent of at least one year of full time study in a Any accredited Higher Education Provider and/or registered training diploma or degree course and has one year of experience working organisation with children over preschool age Second and subsequent Qualified Educator Australia ACT Any RTO registered (or was) to deliver this qualification Certificate IV in Leisure and Health Second and subsequent Qualified Educator CHC40608 Australia ACT Any RTO registered (or was) to deliver this qualification Certificate IV in Lifestyle and Leisure Second and subsequent Qualified Educator Australia ACT Any RTO registered (or was) to deliver this qualification Certificate IV in Outside School Hours Care Second and subsequent Qualified Educator Australia ACT Any RTO registered (or was) to deliver this qualification Certificate IV in School Age Education -

Kindergarten Teachers

KINDERGARTEN TEACHERS Assistant Teacher : Ms. LE THI NGOC Teacher: Ms. Elena Zhukova QUYEN Qualification: Bachelor of Arts (Education) Qualification: Bachelor of Arts Class: International K1/K2 Class: International K1/K2 Assistant Teacher : Ms. LAM THI HUYNH HOA Qualification: Bachelor of Arts (English) Class: International K1/K2 Assistant Teacher : Ms. NGUYEN Teacher: Ms. LINDY BURGESS NGOC PHI PHUNG Qualification : Bachelor of Arts (Sociology and Psychology with honours in Sociology) Graduate Diploma in Early Childhood Education Qualification: Bachelor of Arts (English) Class: International Prep Class: International Prep Assistant Teacher : Ms. NGUYEN Teacher: Ms. BUI THI THANH LOAN DANG QUYNH NHU Qualification : College Graduated (Early Childhood) Qualification: Bachelor of Arts (English) Class: Integrated K1 Class: Integrated K1 Teacher: Ms. NGUYEN PHAM THI Assistant Teacher : Ms. LUONG THI ANH HANG NGA Qualification: Bachelor of Arts (English/International Relationship) #REF! Class: Integrated K2 Teacher: Ms. DO THI NGOC Assistant Teacher : Ms. DUONG YEN PHUONG PHUONG Qualification : Bachelor of Arts - English Linguistics and Literature Qualification: Diploma ( Childhood Certificate of Teaching Methodology Teaching) Class: Integrated Prep Class: Integrated Prep PRIMARY TEACHERS Teacher : Ms. CECILIA SCHUMANN Teacher : Ms. CHU VY Qualification : Bachelor of Education Qualification : Bachelor of Education (English) Class: International Year 1 Class: International Year 1 Teacher : Ms. DIEP NGOC THUY Teacher : Ms. CHRISTINA ONESI TRANG Qualification : Bachelor of Education (Primary & Secondary - Physical Education Qualification : Bachelor of Education and Health) (Primary) Class: International Year 2 Class: International Year 2 Teacher : Ms. DUONG THI QUYNH Teacher : Mr. KYLE PUCHALSKY NHU Qualification : Bachelor of Arts (Major in Education) Certificate in Education Qualification : Bachelor of Arts (English) Class: International Year 3 Class: International Year 3 Teacher : Ms. -

POST NOMINALS 17 February 2021

Quality and Academic Governance POST NOMINALS 17 February 2021 Advanced Certificate in Aboriginal Music Theatre AdvCertAblMusTh Advanced Diploma (Production and Performance) AdvDipProdPerf Advanced Diploma of Costume for Performance AdvDipCostumePerf Advanced Diploma of Dance (Elite Performance) AdvDipDance(EltPerf) Advanced Diploma of Design for Performance AdvDipDesignPerf Advanced Diploma of Lighting for Performance AdvDipLightPerf Advanced Diploma of Live Production, Theatre and Events AdvDipLiveProdTh&Events Advanced Diploma of Live Production, Theatre and Events (Costume) AdvDipLiveProdTh&Events(Costume) Advanced Diploma of Live Production, Theatre and Events (Lighting) AdvDipLiveProdTh&Events(Light) Advanced Diploma of Live Production, Theatre and Events (Props and Scenery) AdvDipLiveProdTh&Events(Props&Scnry) Advanced Diploma of Live Production, Theatre and Events (Sound) AdvDipLiveProdTh&Events(Sound) Advanced Diploma of Music AdvDipMus Advanced Diploma of Music (Classical) AdvDipMus(Class) Advanced Diploma of Music (Contemporary) AdvDipMus(Contp) Advanced Diploma of Music (Jazz) AdvDipMus(Jazz) Advanced Diploma of Music (Music Production) AdvDipMus(MusProd) Advanced Diploma of Music Teaching AdvDipMusTeach Advanced Diploma of Performing Arts (Acting) AdvDipPerfA(Acting) Advanced Diploma of Performing Arts (Acting)(Directing) AdvDipPerfA(Acting)(Dir) Advanced Diploma of Performing Arts (Costume) AdvDipPerfA(Costume) Advanced Diploma of Performing Arts (Dance) AdvDipPerfA(Dance) Advanced Diploma of Performing Arts (Design) AdvDipPerfA(Design) -

Secondary Teachers

SECONDARY TEACHERS Subject Taught Education Email address Bachelor of Arts in Japanese and History, University of Melbourne Bachelor of Science in Mathematics and Chemistry, University of Maths Teacher Melbourne [email protected] Diploma of Education in Secondary Mathematics and Languages, University of Canberra Niaomi Anderson Design Technology Bachelor of Education - Technology & Industrial Arts, University of Teacher/Leader of [email protected] South Australia (UNISA) Learning Deryck Ashsoft Doctor of Philosophy Biochemistry, Indiana University Physics/Science Teacher/ Bachelor of Science Biochemistry, Purdue University [email protected] Leader of Learning Howard Hughes Research Scholar Professional Educator’s License, State of Indiana Justin Babcock University and Career Bachelor of Arts, University of Virginia JD, Washington & Lee [email protected] Advisor University School of Law (International Law Fellow) Lee Baker Bachelor of Education in Physical Education, University of Ballarat PE Teacher [email protected] Diploma Outdoor and Environmental Studies, University of Ballarat Tim Bartle Individuals & Societies/ Post Graduate Certificate in Education, University of Sunderland Psychology/TOK [email protected] Bachelor of Arts, Lehigh University Teacher Batjargal Batmunkh (Bachka) Master of Science, University of Ulster Individuals & Societies Bachelor of Arts Honours in Geography, University of Strathclyde [email protected] Teacher PGCE Geography, Oxford University -

Bachelor of Education 2007

Faculty of Education Studying Education in the Bachelor of Arts For students enrolling from 2007 1 CONTENTS STUDYING EDUCATION IN THE BACHELOR OF ARTS How to enrol THE BACHELOR OF ARTS WITH A MAJOR IN EDUCATION Can I be a teacher with an Education Major? Can I transfer from the Bachelor of Arts to the Bachelor of Education? SUBJECTS IN AN EDUCATION MAJOR THE TESOL PROGRAM THE GRADUATE DIPLOMA IN EDUCATION PLANNED ROLL-OUT OF BACHELOR OF EDUCATION SUBJECTS This booklet is designed for students commencing study in 2007. Students who commenced prior to 2007 should consult with the B.A. (Education) Coordinator and University Undergraduate Handbook. 2 STUDYING EDUCATION IN THE BACHELOR OF ARTS Bachelor of Arts Major in Education is designed for students who are interested in Education as a broad area of study. It is not designed as preparation for entry into the NSW teaching service. This program is for: • Those planning to enter non-teaching professions where they feel they would benefit from a broad understanding of the role of Education in Australian culture and society. These include adult educators, nurses, lawyers, social workers, professionals who will deal with children and families, librarians and historians. • Those who are considering teaching as a profession and may be interested in undertaking the Graduate Diploma in Education (GDE) at the completion of their BA and want to undertake education study. • Students interested in studying TESOL (Teaching English as a Second Language). • International students not intending to teach in Australia but who are interested in taking specialist education subjects. • Those interested in a career in academic institutions, for example as administrators. -

Connect: Education Connect: Education 2 Our FACULTY 4 FIVE REASONS to STUDY EDUCATION 5 Opportunities to EXCEL 6 HEAD of the CLASS 12 STUDY OPTIONS WELCOME

CONNECT: EDUCATION CONNECT: EDUCATION 2 OUR FACULTY 4 FIVE REASONS TO STUDY EDUCATION 5 OPPORTUNITIES TO EXCEL 6 HEAD OF THE CLASS 12 STUDY OPTIONS WELCOME There are a number of reasons why an education qualification from the Faculty of Education at UOW is highly valued. It’s not only the nature of our programs, the international teaching opportunities, the reputation of our staff and our cutting-edge teaching practices, but it’s also our use of the latest educational technology and a graduate employment rate well beyond other similar institutions. These factors contribute to the high quality of the qualification you will obtain with us. In fact, according to the 2010 UOW Student Experience Survey, 98% of all Education students would recommend UOW and 92% of all Education students agree that their course helped them acquire work-related skills. Our Preservice Teacher Education degrees are informed by highly intensive research-lead practices, which means you will be able to teach in a range of school systems: state, independent and Catholic, in Australia and overseas. Our graduates have found jobs all around the world, including the UK, USA and Canada. This booklet contains information about our Faculty as well as providing details of our facilities, resources and procedures across the University that will support you in your studies. I am confident that the opportunities we are able to offer you will ensure that you enjoy your time here. I wish you all the best for your studies. PROFESSOR PAUL CHANDLER DEAN, FACULTY OF EdUCATION EDUCATION 1 WHAT WE DO CONNECT: OUR FACULTY 2 UNIVERSITY OF WOLLONGONG Have you ever had a teacher that inspired or impressed you? That teacher, most likely, helped you achieve your best. -

Education UOWPG2007 21

faculty of education UOWPG2007 21 EDUCATION The postgraduate education programs offered by the Faculty reflect > EDUCATIONAL LEADERSHIP the high level of expertise and industry links the Faculty has been Graduate studies in Educational Leadership provide a broad able to forge through the research undertaken by its academic staff. understanding of educational issues and specialized study to Research programs are supervised by academics in touch with the those who aspire to be leaders in an educational setting and latest global trends in education teaching and methodologies, while those who wish to occupy a policy or evaluation role within a coursework degrees offer sound theoretical foundations and variety of educational enterprises. The programs offer subjects extensive practical skills that address the broader aspects of that explore a range of educational issues including the use of education and training, including strategic planning, management, modern technologies, cross-cultural perspectives and change administration and policy. The Faculty provides students with an factors. The programs also provide an opportunity for students orderly and coherent exposure to critical issues in contemporary to link studies with Master of Business Administration subjects educational theory and practice, as well as avenues for the such as financial management and strategic planning. professional development of teachers, educational administrators and policy makers. > INFORMATION & COMMUNICATION TECHNOLOGIES IN EDUCATION & TRAINING The Faculty offers programs in the following areas: This program is internationally renowned for research and teaching as well as for the innovative software it has designed. > ADULT EDUCATION, HIGHER EDUCATION AND StageStruck and Exploring the Nardoo were developed by the VOCATIONAL EDUCATION & TRAINING team and have won many awards including the European The Adult Education, Higher Education and VET program is Multimedia Manufacturers Award (EMMA) four times. -

Distance Education International Prospectus

DISTANCE EDUCATION INTERNATIONAL PROSPECTUS BR UN EI VIETNAM I BA DU KUALA LUMPUR THE ENGINE OF THE NEW NEW ZEALAND In 2002 Sarah Gibbs struck oil – rosehip oil. So she co-founded the natural cosmetics company Trilogy, taking the product, and brand onto the world stage. Today Trilogy is sold in 16 countries. Sarah Gibbs | Co-founder of Trilogy Bachelor of Business Studies (Accounting) engine.ac.nz Contents 02 Welcome to Massey University 03 About Massey University 04 About this Prospectus 05 Why You Should Choose Massey University 06 What You Can Study Through Massey 07 Choose Massey’s Distance Education Expertise 08 A World-Leading Veterinary School 09 Why the World Bank Chose Massey 10 Why the Singapore Government Chose Massey 11 Why the Royal Brunei Armed Forces Chose Massey 12 College of Business 13 College of Creative Arts 14 College of Education 15 College of Humanities and Social Sciences 16 College of Sciences 17 Short Courses and Professional Development 18 Massey and Worldwide Disaster Management 19 How Massey Supports Second Language Teaching 20 How Distance Learning Works 21 Support for Students 22 Apply to Study at Massey 23 Glossary of Key Terms 24 Contact Massey University Welcome to Massey University Massey University is New Zealand’s defining University and has a In recent years New Zealanders have been increasingly using their long and proud tradition of academic and research excellence. Among unique Kiwi world view to achieve great things, globally. Massey is Australasia’s tertiary institutions Massey is unique. playing a central role in this by aiming to be the engine of this 'new' New Zealand of the 21st Century. -

Pathways Programs to University in 2022 There Are Many Different Ways to Get to the Same Destination, and That Applies to University Too

Pathways Programs to University in 2022 There are many different ways to get to the same destination, and that applies to university too. Sometimes students do not quite meet the entry criteria to go straight into a university course – maybe their ATAR was not high enough, or they did not attain the minimum study score in a prerequisite subject. The encouraging thing is that many universities have recommended pathway courses to degrees they offer. Below are many of these pathway schemes: Box Hill Institute Pathways to ACU, Deakin, and La Trobe Box Hill Institute places a strong emphasis on providing students with practical knowledge in their chosen area of study, preparing students for further study at Australian Catholic University (ACU), Deakin University, and La Trobe University. Courses include business, nursing, sport development, accounting, commerce, and IT and some of these pathway courses are on offer to both domestic and international students. For a list of pathway courses (some of which are guaranteed pathways) from Box Hill Institute to ACU, Deakin University, and La Trobe University, visit Pathways from Box Hill Institute to University. Carlton College of Sport Diplomas to La Trobe University Carlton College of Sport offers two one-year diploma courses that can articulate into the second year of bachelor degrees at La Trobe University. Diploma of Sport Coaching and Development into a number of sport-related degrees . Diploma of Elite Sport Business into various business-related degrees Find out more at Carlton College of Sport Chisholm Institute to La Trobe University Chisholm Institute, in partnership with La Trobe University, has offered a range of degrees over a number of years. -

Course Handbook

COURSE DIPLOMA OF HANDBOOK EDUCATION STUDIES OVERVIEW YOUR PATHWAY TO TEACHING Program Director Stephen Brinton Level AQF Level 5 (Higher Education) With lecturers who bring not only Qualification Diploma academic expertise but practical experience Subjects 8 into the classroom, the AC Diploma of Education Studies will IELTS 5.5 provide an educational experience of holistic CRICOS Code 102799G formation which prepares students to ASCED Code 070103 change the world. Accreditation Self-accredited Course Length 1 year full-time; up to 4 years part-time The Diploma of Education Studies is a nested higher education award in the Bachelor of Education (Primary) and Bachelor of Education (Secondary), with core skills in writing and research, as well as the AC core value of Christian Worldview. It can be a destination course, pathway, or exit point, thus allowing flexibility for students who may wish to start with a short sub-bachelor course before committing to a Bachelor degree or for students who need to exit the Bachelor of Education earlier than intended, due to unforeseen personal or professional reasons. Graduates of the Diploma of Education Studies may find employment in educational institutions (faith-based, government and non-government), not-for-profit and mission-focused organisations, community service- orientated positions, and positions that require skills in research and critical thinking. Last updated: February 2021 1 COURSE DIPLOMA OF HANDBOOK EDUCATION STUDIES AC GRADUATE ATTRIBUTES Christian Worldview A knowledge of the Christian story, derived from the Scriptures and tradition of the church. An awareness of the implications of this story for self-identity in the context of local and global communities. -

Divisions and Their Departments

Part 2 Div and Dept UG 2007.qxd 11/20/2006 9:06 AM Page 137 DIVISIONS AND THEIR DEPARTMENTS Transfer between courses Australian Centre for Any student wishing to change his or her degree to anoth- er degree must meet the requirements set out in Part 1 of Educational Studies this Handbook, and a Request to Transfer Degree Course The Australian Centre for Educational Studies (ACES) form must be completed. brings together Macquarie University’s expertise in edu- cation across the lifespan – from early childhood to adult- Australian Centre for Educational hood, and includes a focus on learners with special edu- Studies enquiries cation needs. ACES is dedicated to the preparation of teachers and professionals who are well equipped to meet Room: X5B 387 the needs of the rapidly changing contexts of contempo- Phone: +61 2 9850 9898 rary teaching and learning, and who will become leaders Fax: +61 2 9850 9891 in their fields as well as providing leadership within their Email: [email protected] communities. The Division comprises two Departments Website: www.aces.mq.edu.au and one Centre: INSTITUTE OF EARLY CHILDHOOD Institute of Early Childhood, specialising in the prepara- tion of teachers of children aged 0–8 years in long day The Institute of Early Childhood is the major provider of care, pre-school and K–2 in primary school; early childhood teacher education in NSW, offering courses at undergraduate and postgraduate levels. Mia- School of Education, specialising in the preparation of Mia Child and Family Study Centre is an integral part of New South Wales primary and secondary school teach- the Institute and provides unique opportunities for staff ers; and research and observational studies for units offered in Macquarie University Special Education Centre, special- child development, curriculum studies and early child- ising in preparing students for the advanced professional hood education.