Macedward Leach and the Founding of the Folklore Program at the University of Pennsylvania

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Buck Owens Obituary

Obituary of Buck Owens: March 27, 2006 By: Dave Hoekstra Buck Owens was more than a voice in country music. He was an American metaphor for the clarion of possibility after The Grapes of Wrath migration to California. Alvin Edgar "Buck" Owens was a honky-tonk singer, a TV star -- best known for his role in "Hee-Haw" -- and an entrepreneur who owned radio and television stations in Bakersfield, Calif. He was a good soul, one who would fly from Bakersfield to Portland, Ore., as he did in March 2005 to surprise compatriot Merle Haggard, who was opening for Bob Dylan. The depth of the moment was understood. With Mr. Owens standing stage right in a resplendent brown and black cowboy jacket, Dylan took a chance on Haggard's "Sing Me Back Home." Mr. Owens died Saturday at home in Bakersfield. He was 76. On Sunday, CMT.com reported the cause of death as a heart attack. He grew old, but his songs never became tired. In recent years he stopped touring outside of California, but he still managed to capture a new generation of fans that included Dwight Yoakam, Steve Earle and the Bottle Rockets. In the late 1990s, John Soss of Chicago's Jam Productions held an annual Buck Owens birthday party at Schubas that featured artists as diverse as soul singers Otis Clay and Mavis Staples, and country-rocker Jon Langford. Mr. Owens crossed borders he never would have dreamed of as a child when he headed west with his sharecropper parents from the Red River Valley near Sherman, Texas. -

ALBUMS BARRY WHITE, "WHAT AM I GONNA DO with BLUE MAGIC, "LOVE HAS FOUND ITS WAY JOHN LENNON, "ROCK 'N' ROLL." '50S YOU" (Prod

DEDICATED TO THE NEEDS OF THE MUSIC RECORD INCUSTRY SLEEPERS ALBUMS BARRY WHITE, "WHAT AM I GONNA DO WITH BLUE MAGIC, "LOVE HAS FOUND ITS WAY JOHN LENNON, "ROCK 'N' ROLL." '50s YOU" (prod. by Barry White/Soul TO ME" (prod.by Baker,Harris, and'60schestnutsrevved up with Unitd. & Barry WhiteProd.)(Sa- Young/WMOT Prod. & BobbyEli) '70s savvy!Fast paced pleasers sat- Vette/January, BMI). In advance of (WMOT/Friday'sChild,BMI).The urate the Lennon/Spector produced set, his eagerly awaited fourth album, "Sideshow"men choosean up - which beats with fun fromstartto the White Knight of sensual soul tempo mood from their "Magic of finish. The entire album's boss, with the deliversatasteinsupersingles theBlue" album forarighteous niftiest nuggets being the Chuck Berry - fashion.He'sdoingmoregreat change of pace. Every ounce of their authored "You Can't Catch Me," Lee thingsinthe wake of currenthit bounce is weighted to provide them Dorsey's "Ya Ya" hit and "Be-Bop-A- string. 20th Century 2177. top pop and soul action. Atco 71::14. Lula." Apple SK -3419 (Capitol) (5.98). DIANA ROSS, "SORRY DOESN'T AILWAYS MAKE TAMIKO JONES, "TOUCH ME BABY (REACHING RETURN TO FOREVER FEATURING CHICK 1116111113FOICER IT RIGHT" (prod. by Michael Masser) OUT FOR YOUR LOVE)" (prod. by COREA, "NO MYSTERY." No whodunnits (Jobete,ASCAP;StoneDiamond, TamikoJones) (Bushka, ASCAP). here!This fabulous four man troupe BMI). Lyrical changes on the "Love Super song from JohnnyBristol's further establishes their barrier -break- Story" philosophy,country -tinged debut album helps the Jones gal ingcapabilitiesby transcending the with Masser-Holdridge arrange- to prove her solo power in an un- limitations of categorical classification ments, give Diana her first product deniably hit fashion. -

Acoustic Guitar

794 ACOUSTICACOUSTIC GUITARGUITAR ACOUSTIC THE ACOUSTIC INCLUDES THE NEW TAB NEW GUITAR GUITAR COMPLETE INCLUDES MAGAZINE’S PRIVATE METHOD, ACOUSTIC TAB LESSONS VOLUME 1 BOOK 2 GUITAR METHOD 24 IN-DEPTH LESSONS by David Hamburger LEARN TO PLAY USING String Letter Publishing String Letter Publishing THE TECHNIQUES & With this popular guide and Learn how to alternate the bass SONGS OF AMERICAN two-CD package, players will notes to a country backup ROOTS MUSIC learn everything from basic pattern, how to connect chords by David Hamburger techniques to more advanced with some classic bass runs, and String Letter Publishing moves. Articles include: Learning to Sight-Read (Charles how to play your first fingerpicking patterns. You’ll find out A complete collection of all three Acoustic Guitar Method Chapman); Using the Circle of Fifths (Dale Miller); what makes a major scale work and what blues notes do to books and CDs in one volume! Learn how to play guitar Hammer-ons and Pull-offs (Ken Perlman); Bass Line a melody, all while learning more notes on the fingerboard with the only beginning method based on traditional Basics (David Hamburger); Accompanying Yourself and more great songs from the American roots repertoire American music that teaches you authentic techniques and (Elizabeth Papapetrou); Bach for Flatpickers (Dix – especially from the blues tradition. Songs include: songs. Beginning with a few basic chords and strums, Bruce); Double-Stop Fiddle Licks (Glenn Weiser); Celtic Columbus Stockade Blues • Frankie and Johnny • The Girl you’ll start right in learning real music drawn from blues, Flatpicking (Dylan Schorer); Open-G Slide Fills (David I Left Behind Me • Way Downtown • and more. -

AMERICAN FOLKLORE ARCHIVES in THEORY and PRACTICE Andy

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by IUScholarWorks ARCHIVING CULTURE: AMERICAN FOLKLORE ARCHIVES IN THEORY AND PRACTICE Andy Kolovos Submitted to the faculty of the University Graduate School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Folklore and Ethnomusicology, Indiana University October 2010 Accepted by the Graduate Faculty, Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Doctoral Committee Gregory Schrempp, Ph.D. Moira Smith, Ph.D. Sandra Dolby, Ph.D. James Capshew, Ph.D. September 30, 2010 ii © 2010 Andrew Kolovos ALL RIGHTS RESERVED iii For my Jenny. I couldn’t have done it without you. iv Acknowledgements First and foremost I thank my parents, Lucy and Demetrios Kolovos for their unfaltering support (emotional, intellectual and financial) across this long, long odyssey that began in 1996. My dissertation committee: co-chairs Greg Schrempp and Moira Smith, and Sandra Dolby and James Capshew. I thank you all for your patience as I wound my way through this long process. I heap extra thanks upon Greg and Moira for their willingness to read and to provide thoughtful comments on multiple drafts of this document, and for supporting and addressing the extensions that proved necessary for its completion. Dear friends and colleagues John Fenn, Lisa Gabbert, Lisa Gilman and Greg Sharrow who have listened to me bitch, complain, whine and prattle for years. Who have read, commented on and criticized portions of this work in turn. Who have been patient, supportive and kind as well as (when necessary) blunt, I value your friendship enormously. -

Franklin County KS Obits 1965-1999

Obituaries in Ottawa, Kansas Newspapers 1965-1999 In 2003-2004 Alena Loyd retyped the existing Ottawa Annals for 1864-1964 and created new annals for 1965-2003 using microfilmed copies of “The Ottawa Times” and “The Ottawa Herald.” While going through the papers for 1965-2003 she also abstracted the obituaries. Alena used the weekly “The Ottawa Times” for 1965-August 24, 2000 and “The Ottawa Herald” (published Mon-Sat) for August 25, 2000-2003. This document is in Word and specific names may be searched using the computer’s Edit/Find feature. To obtain a copy of an obituary, contact Franklin County Genealogical Society, PO Box 353, Ottawa, KS 66067. Their research fees are currently $10.00/hour plus copies and postage. Library staff can relay to them an email order stating that these fees are acceptable. Researchers may also conduct their own research by asking their local library to borrow microfilm of Ottawa, Kansas newspapers from Kansas State Historical Society, Topeka, KS 1965 Jan. 7 –Alta E. Brantingham, Mrs. Laura Mollett, Mrs. Cora Ellen Keith, Mrs. Bonnie E. Henry, Lina A. Tulloss, Ralph W. Selby, Ray S. Miskimon and John W. Beekman passed away. Jan. 14 – Henry W. Fleer, Guy H. Settle and Mrs. Jeff Haggard passed away. Jan. 21 – Roy Taylor, Mrs. Anna Pierson, Mrs. Minnie Niehoff, W. E. Chapman, Mrs. L. B. Fenton, Herbert G. Lemon, Mrs. Nora B. Jones and Homer T. Rule, Sr. passed away. Jan. 28 – Wm. Albert Richardson, Mrs. Elsie M. Cain, Lori Colleen Norton, Mrs. Grace Silvius, Albert K. Dehn and Earl R. -

Acoustic Guitar

45 ACOUSTIC GUITAR THE CHRISTMAS ACOUSTIC GUITAR METHOD FROM ACOUSTIC GUITAR MAGAZINE COMPLETE SONGS FOR ACOUSTIC BEGINNING THE GUITAR GUITAR ACOUSTIC METHOD GUITAR LEARN TO PLAY 15 COMPLETE HOLIDAY CLASSICS METHOD, TO PLAY USING THE TECHNIQUES & SONGS OF by Peter Penhallow BOOK 1 AMERICAN ROOTS MUSIC Acoustic Guitar Private by David Hamburger by David Hamburger Lessons String Letter Publishing String Letter Publishing Please see the Hal Leonard We’re proud to present the Books 1, 2 and 3 in one convenient collection. Christmas Catalog for a complete description. first in a series of beginning ______00695667 Book/3-CD Pack..............$24.95 ______00699495 Book/CD Pack...................$9.95 method books that uses traditional American music to teach authentic THE ACOUSTIC EARLY JAZZ techniques and songs. From the folk, blues and old- GUITAR METHOD & SWING time music of yesterday have come the rock, country CHORD BOOK SONGS FOR and jazz of today. Now you can begin understanding, GUITAR playing and enjoying these essential traditions and LEARN TO PLAY CHORDS styles on the instrument that truly represents COMMON IN AMERICAN String Letter Publishing American music: the acoustic guitar. When you’re ROOTS MUSIC STYLES Add to your repertoire with done with this method series, you’ll know dozens of by David Hamburger this collection of early jazz the tunes that form the backbone of American music Acoustic Guitar Magazine and swing standards! The and be able to play them using a variety of flatpicking Private Lessons companion CD features a -

Merle Haggard and the Strangers Mama Tried Mp3, Flac, Wma

Merle Haggard And The Strangers Mama Tried mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Folk, World, & Country Album: Mama Tried Country: US Released: 1968 Style: Country MP3 version RAR size: 1733 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1542 mb WMA version RAR size: 1960 mb Rating: 4.1 Votes: 282 Other Formats: AIFF MOD WAV MIDI XM DXD MP1 Tracklist Hide Credits A1 Mama Tried 2:10 Green Green Grass Of Home A2 3:13 Written-By – Curley Putnam* Little Ole Wine Drinker Me A3 2:36 Written-By – Jennings*, Mills* In The Good Old Days (When Times Were Bad) A4 2:43 Written-By – Dolly Parton I Could Have Gone Right A5 2:31 Written-By – Mel Tillis A6 I'll Always Know 2:20 B1 The Sunny Side Of My Life 2:08 Teach Me To Forget B2 3:13 Written-By – Leon Payne Folsom Prison Blues B3 2:46 Written-By – Johnny Cash Run 'Em Off B4 2:50 Written-By – Oney Wheeler*, T. Lee* B5 You'll Never Love Me Now 2:45 Too Many Bridges To Cross Over B6 2:26 Written-By – Dallas Frazier Credits Bass – Jerry Ward Drums – Eddie Burris* Guitar [Lead] – Roy Nichols Liner Notes – Mike Hoyer Photography By [Cover] – Ken Veeder Piano – George French* Producer – Ken Nelson Steel Guitar – Norm Hamlett* Written-By – Merle Haggard (tracks: A1, A6, B1, B5) Notes 3rd pressing orange label with gold Capitol logo on bottom Barcode and Other Identifiers Matrix / Runout (Etched, Runout Side A): ST-1-2972-H-3: Matrix / Runout (Etched, Runout Side B): ST-2-2972-H-3: Other versions Title Category Artist Label Category Country Year (Format) Merle Capitol Haggard And Mama Tried Records, ST 2972, ST-2972 -

Revista Completa En Formato

ISSN 0327-0734 Revista de Investigaciones Folclóricas vol. 14 diciembre de 1999 Esta revista se publica anualmente para el mes de diciembre Buenos Aires, Argentina Revista de Investigaciones Folclóricas vol.14, diciembre de 1999 Directora Martha Blache Comité Editorial Isabel Aretz - Presidente del Centro Argentino de Etnomusicología y Folklore, Argentina Ana M. Cousillas - Universidad de Buenos Aires Manuel Dannemann - Universidad de Chile Ana María Dupey - Universidad de Buenos Aires Rosan A. Jordan - Louisiana State University Flora Losada - Universidad Nacional de Jujuy Juan Angel Magariños de Morentin - Universidad Nacional de La Plata Alicia Martín - Universidad de Buenos Aires Secretaria de Redacción Mirta Bialogorski Comité de Redacción Patricia Coto de Atilio Fernando Fischman Noemí Elena Hourquebie Carmen Vayá Normas editoriales para la presentación de colaboraciones 1. trabajos inéditos escritos en castellano o en portugués. 2. su extensión no deberá exceder las 25 páginas de tamaño A4, a doble espacio, letra Times New Roman N° 12. 3. al pie de la primera página indicar; a) la instituciión a la que pertenece el autor/es, b) preferentemen- te el/los e-mail/s o en su defecto la dirección postal de la institución a la que pertenece el autor/es. 4. notas al final de la colaboración. 5. para las referencias bibliográficas seguir los criterios adoptados por esta Revista. 6. los trabajos deberán ser acompañados de dos resúmenes, uno escrito en castellano y el otro en inglés. Los resúmenes no deberán exceder las 10 líneas. Además de los resúmenes se deberán incluir no más de 5 palabras claves que identifiquen lo más significativo del texto. -

The Center for Popular Music Middle Tennessee State University, Murfreesboro, Tn

THE CENTER FOR POPULAR MUSIC MIDDLE TENNESSEE STATE UNIVERSITY, MURFREESBORO, TN JESSE AUSTIN MORRIS COLLECTION 13-070 Creator: Morris, Jesse Austin (April 26, 1932-August 30, 2014) Type of Material: Manuscript materials, books, serials, performance documents, iconographic items, artifacts, sound recordings, correspondence, and reproductions of various materials Physical Description: 22 linear feet of manuscript material, including 8 linear feet of Wills Brothers manuscript materials 6 linear feet of photographs, including 1 linear foot of Wills Brothers photographs 3 boxes of smaller 4x6 photographs 21 linear feet of manuscript audio/visual materials Dates: 1930-2012, bulk 1940-1990 RESTRICTIONS: All materials in this collection are subject to standard national and international copyright laws. Center staff are able to assist with copyright questions for this material. Provenance and Acquisition Information: This collection was donated to the Center by Jesse Austin Morris of Colorado Springs, Colorado on May 23, 2014. Former Center for Popular Music Director Dale Cockrell and Archivist Lucinda Cockrell picked up the collection from the home of Mr. Morris and transported it to the Center. Arrangement: The original arrangement scheme for the collection was maintained during processing. The exception to this arrangement was the audio/visual materials, which in the absence of any original order, are organized by format. Collection is arranged in six series: 1. General files; 2. Wills Brothers; 3. General photographs; 4. Wills Brothers photographs; 5. Small print photographs; 6. Manuscript Audio/Visual Materials. “JESSE AUSTIN MORRIS COLLECTION” 13-070 Subject/Index Terms: Western Swing Wills, Bob Wills, Johnnie Lee Cain’s Ballroom Country Music Texas Music Oklahoma Music Jazz music Giffis, Ken Agency History/Biographical Sketch: Jesse Austin Morris was editor of The Western Swing Journal and its smaller predecessors for twenty years and a well-known knowledge base in western swing research. -

Simon Bronner

SIMON J. BRONNER, Ph.D. Dean, College of General Studies University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee CONTENTS Administration...3 Administrative Highlights…4 Professorial Posts ...6 Degrees...7 Certificates and Continuing Education...7 Publications...8 Books...8 Special Issues and Monographs...11 Book Chapters...12 Forewords and Introductions to Books and Special Issues...18 Essays in Reference Works...20 Journal Articles...25 Memorial Essays...32 Magazine Essays...33 Newspaper and Newsletter Essays...35 Translations...35 Reviews...35 American Material Culture and Folklife Series...40 Pennsylvania German History and Culture Series...42 Material Worlds Series...43 Studies in Folklore and Ethnology…41 Editorial Positions...44 Books...44 Encyclopedias and Atlases...44 Journals...45 Newsletters and Magazines...46 Moderated Lists...46 1 Simon J. Bronner CV Recordings...47 Awards...45 Scholarship...48 Teaching and Service...49 Fellowships, Grants, and Scholarships...53 Invited Addresses...51 Conferences Organized...60 Conference Panels Chaired...62 Positions Held in Scholarly Societies...64 Exhibitions and Museum Positions...66 Consultation and Scholarly Service...67 Reports for Scholarly Presses...71 Reports for Scholarly Journals...72 Evaluation Reports for Universities...73 University Service...75 Task Forces and Special Committees...75 Search Committees...78 Tenure, Promotion, and Administrative Review Committees...79 Student Organization Advising...80 Community Service...81 Public Festival Management and Planning...82 Ph.D. Dissertations and Committees...83 Graduate Theses...86 Biographical Listings...95 2 Simon J. Bronner CV ADMINISTRATION Dean, College of General Studies, University of Wisconsin Milwaukee, since 2019. Chief Executive and Academic Officer. Faculty Development, Office of the Dean of Arts, Sciences, and Business, Missouri University of Science and Technology, Rolla, 2018-2019. -

Missouri State Archives Finding Aid 133.3

Missouri State Archives Finding Aid 133.3 OFFICE OF ADJUTANT GENERAL MISSOURI VETERANS HOME (ST. JAMES) APPLICATIONS, ca. 1912- 1994 Abstract: Applications (ca. 1912-1994) to the Missouri Veterans Home at St. James, formerly known as the Federal Soldiers’ Home. Extent: 29.2 cubic ft. (73 boxes) Physical Description: Paper Location: MSA Stacks ADMINISTRATIVE INFORMATION Alternative Formats: Applications and inmate registers up to 1929 are available as digital images on the Missouri Digital Heritage website. Access Restrictions: Applications with social security numbers must be given to patrons in alternate form. Medical information may be restricted. Publication Restrictions: Copyright is in the public domain for state records. Researchers bear sole responsibility for following applicable copyright laws. Acquisition Information: Accession 2002-0205. Processing Information: Processing completed by Mary Kay Coker on July 29, 2003. HISTORICAL AND BIOGRAPHICAL NOTES The Missouri Veterans Home (St. James) was originally a home for Union soldiers and was known as the Federal Soldiers’ Home of Missouri until 1977. It was established in 1896 by the Women’s Relief Corps and the Grand Army of the Republic. MISSOURI VETERANS HOME (ST. JAMES) APPLICATIONS, ca. 1912-1994 Extent: 29.2 cubic ft. (73 legal-size hollinger boxes) Arrangement: By application number Scope and Content This series contains the original applications and re-admissions for the Missouri Veterans Home (St. James). Almost all early applications are missing up to #1300. As such, it is an incomplete list of residents at the home. However, information on early residents can be found in the partially indexed series Inmate Registers. After #1300, only an occasional application is missing in this series. -

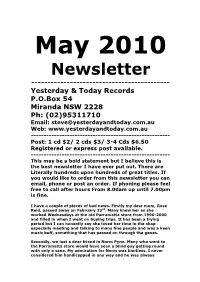

Newsletter May 2010

May 2010 Newsletter ------------------------------------------- Yesterday & Today Records P.O.Box 54 Miranda NSW 2228 Ph: (02)95311710 Email: [email protected] Web: www.yesterdayandtoday.com.au ------------------------------------------------------ Post: 1 cd $2/ 2 cds $3/ 3-4 Cds $6.50 Registered or express post available. ------------------------------------------------------ This may be a bold statement but I believe this is the best newsletter I have ever put out. There are Literally hundreds upon hundreds of great titles. If you would like to order from this newsletter you can email, phone or post an order. If phoning please feel free to call after hours From 8.00am up until 7.00pm is fine. I have a couple of pieces of bad news. Firstly my dear mum, Rose Reid, passed away on February 23rd. Many knew her as she worked Wednesdays at the old Parramatta store from 1990-2000 and filled in when I went on buying trips. It has been a trying period but I can honestly say she loved her time in the shop especially meeting and talking to many fine people and was a keen music buff, something that has passed on through the genes. Secondly, we lost a dear friend in Norm Pyne. Many who went to the Parramatta store would have seen a blind guy getting round with only a cane. My admiration for Norm was limitless. I never considered him handicapped in any way and he was always thankful for his independence. It is a sad irony of life that it is probably this independence which saw him involved in an horrific accident which cost him his life.