Gates Booklet, 2011

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sandford Parks Lido Conservation Plan

SANDFORD PARKS LIDO CONSERVATION PLAN 1 SANDFORD PARKS LIDO CONSERVATION PLAN A Pools and Access/Activity Areas 45 Area A1 Main pool and poolside Contents Area A2 Walkways Area A3 Sun decks Summary 4 Area A4 Lawns Area A5 Children’s pool and poolside Introduction 5 B Buildings 47 1 Background Information 8 B1 South Range: Entrance and offices, changing rooms and toilets B2 North Range: Café and Terraces 2 Aims and Objectives of the Conservation Management Plan 8 B3 Filter House B4 Plant House 3 Stakeholders and Consultation 10 C Exterior Areas 50 4 Understanding Sandford Parks Lido 12 C1 Café garden 4.1. Origins and Development 12 C2 Service area 4.2 Historical Context 12 C3 East zone (Reach Fitness) 4.3 The Design Concept 16 C4 Car park 4.4 Engineering and Water Treatment 18 4.5 Site Development after 1945 20 D Planting 51 5 Setting, Access and Neighbours 25 9 Educational Policy 53 5.1 The Setting of the Lido 25 5.2 Access to and around the Lido 26 5.3 Neighbours and the Hospital 26 10 References 56 6 The Values of the Lido 27 6.1 Changing Attitudes 27 6.2 Defining Values 28 Appendices 61 6.3 The Values 28 Appendix 1 Shortlist of the most architecturally and 6.3.1 Historic Value 28 historically significant lidos 6.3.2 Aesthetic and Monumental Value 29 6.3.3 Community and Recreational Value 31 Appendix 2 Link Organisations 62 6.3.4 Educational Value 36 Appendix 3 Management Data 64 6.3.5 Functional and Economic Value 37 1 Visitor numbers 7 Management Issues 38 2 Opening Times 7.1. -

The Portland Square and Albert Place District: Land, Houses and Early Occupants As Originally Published in the Cheltenham Local History Society Journal

The Portland Square and Albert Place District: land, houses and early occupants As originally published in the Cheltenham Local History Society Journal. Reproduced with the kind permission of the Author MIKE GRINDLEY T'is gone with its thorns and its roses, With the dust of dead ages to mix! Time's charnel forever encloses The year Eighteen Hundred and Six THUS THE LOCAL PRESS i alluded to the 1806 Cheltenham Inclosure Award which allotted ownership of areas of potential building land on the north side of the town, including the piece of orchard that later became the Portland Square development. Numbered 223 under the Award, it bordered the Prestbury Road opposite the SE edge of the future Pittville Estate; to the south were the lands on which the streets of Fairview came to be built. Detail from Merrett’s 1834 map of Cheltenham, showing extent of Portland Square development by then. THE LAND AND ITS OWNERS: 1739 1824 The earliest mention of land so far seen in Portland Square deeds ii is in the November 1739 Will of Samuel Whithorne Esq., of the ancient Charlton Kings family. On 2 January 1801 his grandson, John Whithorne the younger, sold to William Wills of Cheltenham, gent., for £200 ‘all those three acres and a half of arable land [in four lots] lying dispersedly in and about a field in the parish of Cheltenham called Sandfield, otherwise Prestbury Field, otherwise Whaddon Field’. The tenant was John Peacey, a Charlton Kings plasterer. William Wills was a peruke maker of the then 48 High Street, who died in Spring 1804, leaving all his houses and lands to his widow Penelope, their son William to inherit on her death. -

Pittville Park

Pittville Park Green Flag Award and Green Heritage Site Management Plan 2016 – 2026 Reviewed January 2020 1 2 Contents 1.0 Introduction .............................................................................................................................................. 5 2.0 General information about the park .......................................................................................................... 8 2.1 Legal Issues ................................................................................................................................................... 8 2.2 Strategic Significance of Pittville Park ........................................................................................................ 10 2.3 Surveys and Assessments undertaken ........................................................................................................ 13 2.4 Community Involvement ............................................................................................................................ 13 2.5 Current management structure .................................................................................................................. 15 3.0 Historical Development............................................................................................................................ 18 3.1 The heritage importance of the park .......................................................................................................... 18 3.2 History of the park - timeline ..................................................................................................................... -

Rivershill-Cheltenham-2020 05 12.Pdf

Introducing Rivershill, a rare collection of 1, 2 and 3 bedroom apartments and penthouses situated in the heart of historic Cheltenham, a stone’s throw from sophisticated Montpellier. An exciting collection of 56 apartments and 7 penthouses, all with allocated parking. Rivershill offers bright, airy and well-proportioned living space with private outside areas, as well as communal spaces – including a purpose-built basement gym and studio. RIVERSHILL, CHELTENHAM CGI for illustrative purposes only. VISIT rivershillcheltenham.com CGI for illustrative purposes only. RIVERSHILL, CHELTENHAM CGI for illustrative purposes only. illustrative for CGI VISIT rivershillcheltenham.com fit for purpose With its own purpose-built gym and studio area, Rivershill is more than equipped to cater to your health and wellbeing needs. The gym includes a wide selection of free weights, treadmills, stationary bikes and a studio room for exercise. With a large space and clean, minimalist design, Rivershill’s exclusive fitness facilities ensure residents have ample room to relax, energise and socialise. CGI for illustrative purposes only. RIVERSHILL, CHELTENHAM WAITROSE RIVERSHILL CHELTENHAM MONTPELLIER IMPERIAL & PARTNERS LADIES COLLEGE GARDENS SQUARE HOTEL DU VIN THE IVY NO. 131 DISTANCES & JOURNEY TIMES FROM RIVERSHILL HOTEL DU VIN 2 minute walk / 0.2 mile / 1 minute drive MONTPELLIER STREET (BOUTIQUES) 3 minute walk / 0.2 mile / 2 minute drive THE PROMENADE 4 minute walk / 0.3 mile / 2 minute drive WAITROSE & PARTNERS 5 minute walk / 0.3 mile / 2 minute drive NO. 131 6 minute walk / 0.4 mile / 2 minute drive IMPERIAL SQUARE GARDENS 6 minute walk / 0.4 mile / 2 minute drive THE IVY 10 minute walk / 0.5 mile / 3 minute drive CHELTENHAM SPA TRAIN STATION 16 minute walk / 0.8 mile / 3 minute drive PITTVILLE PARK 24 minute walk / 1.2 mile / 8 minute drive CHELTENHAM RACE COURSE 32 minute walk / 1.9 mile / 9 minute drive MONTPELLIER Source: Google Maps VISIT rivershillcheltenham.com The Cheltenham Gold Cup is the pinnacle event of the Jumping season. -

Take a Walk Things to See and Do

The Strand & Upper High St Town Centre The Brewery Quarter & Lower High St St Pa uls Arriving by Train? M5 North Rd 40 Cheltenham Racecourse Pittville Park & Pump Rooms 1. Sandford Park Alehouse 16. Copa 32. 2 Pigs For a pleasant fifteen minute walk into the town centre, stroll down the Honeybourne Tewk nd St University Of Gloucestershire CAMRA’s National Pub of the Year 2015, with a great selection of Modern, spacious and family friendly venue, serving good food all day. Down ‘n’ dirty rock club, loads of fun. Also one of Cheltenham’s 85 se Pittville Park Tesco Francis Close Hall esbury Rdown ales and beers from all over the world. Welcoming atmosphere The large seating area to the front is people-watching heaven. best live music venues, giving opportunities for young bands. Line cycle/footpath. You can also make Superstore T and good beer garden, or inside why not try your hand at billiards! use of the D and E buses which run Cheltenham Town FC approximately every ten minutes. Swindon Rd 17. Whittle Taps 33. Smokey Joe’s ester Rd 2. The Swan esham Rd Once the Slug and Lettuce, now a trendy bar serving craft beers and 50’s Americana themed diner, this gorgeously quirky venue serves Glouc Ev A large pub hosting some great live music. Tucked away sofas, a some great comfort food within a quirky industrial interior. shakes, pancakes and more recently bottled beers, wine and estbury Rd pretty conservatory and enormous picnic tables in the outdoor cocktails. Don’t miss. Pr Winston Churchill 39 87 Honeyb L area to the rear. -

1 Pittville Crescent

1 Pittville CresCent Gross internal area (approx) House: 390 sq m / 4,198 sq ft Garage: 46 sq m / 498 sq ft Total: 436 sq m / 4,696 sq ft 1 Pittville CresCent For identification only. Not to scale. Apartment Ground Floor Self contained apartment Lower Ground Floor First Floor Second Floor Services Local Authority Viewing Important Notice Savills, their clients and any joint agents give notice that: 1. They are not authorised to make or give any representations or warranties Mains water, electricity, gas and Cheltenham Borough Council. Strictly by appointment with Savills in relation to the property either here or elsewhere, either on their own behalf or on behalf of their client or otherwise. They assume no responsibility for drainage. Tel: 01242 262 626. Cheltenham. any statement that may be made in these particulars. These particulars do not form part of any offer or contract and must not be relied upon as statements or representations of fact. 2. Any areas, measurements or distances are approximate. The text, photographs and plans are for guidance only and are not necessarily comprehensive. It should not be assumed that the property has all necessary planning, building regulation or other consents and Savills have not Cheltenham • GlouCestershire Postcode tested any services, equipment or facilities. Purchasers must satisfy themselves by inspection or otherwise. 3. The reference to any mechanical or electrical GL52 2QZ equipment or other facilities at the property shall not constitute a representation (unless otherwise stated) to its state or condition or that it is capable of fulfilling its intended function, and prospective purchasers / tenants should satisfy themselves as to the fitness of such equipment for their requirements. -

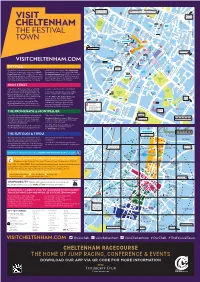

Cheltenham Racecourse (Map Ref E1) the Everyman Theatre (Map Ref D4) D H M B E Lk R S a Park Priory Th D Ed

n Tesco t e A4019 to Tewkesbury, t e e Y d r n l R e Pittville Pump Room, Leisure at Cheltenham, W d M5 North Junction 10, a e U r a EL R d L t L b B I l R T S Racecourse, Park & Ride and A435 to Evesham N G M Gallagher Retail Park ’s D T S D l s O A E D R ’ A N R R ER u l RO P T a u O A S h k D E P a R n C Y t c t U t P r i B4632 to A t e w O S t o w L e e C M a G S s r la d A W N t r L Winchcombe n e e e A 4 r n R 0 E u S S c e t u q e H l 1 L r y u l n & Broadway 9 S n a S i e O S B e r PO W l e e v d IN l E l t D t D O a v t a A e N C V i O n A l E R a M e O r P R r A u en Y t t D n ce R Winston D o R S e o BU s ad T M H g e PITTVILLE Churchill I r n ES a G n t P H i o PR r S o CIRCUS k Memorial S K t T t s M r e T ’ E t e R l S Holst t E l S Gardens E u s a e ’ t E R t r a Birthplace n r t T e e e P T S g e e e S Trinity Museum d t t r c t r n t S S o t a Long Millbrook l D S o S e S The Church q t e P Stay r r N Roundabout e i G a e t t h u v Brewery A Se h t t t n lki H B S L rk S o s S e r a B tre r i e et o n Quarter d o T L lm n r r e n R on G o o n g N y t e i o R y v f a t d G All Saints t e n O i len b e x s S t f W a n al o H s e T P i e Y l S t O t w o tre Church a u D et a g M r e rk e r S re Citizens S o t y n St t P r a T r St w B s A Warwick t e e S a n C N y s R S D Advice n o S e h t a h G Place d s W a & A h e A m g P t e R a o a e r E e n y t o St James’ r J n c T l r O K e i s o ’S d t b n a o e R R R n n n o l d O n o e a W s Roundabout p e N A e p m a r n R P n D b e n l r r S R k Chester e a C r t d o A H l -

Friends of Pittville

Friends of Pittville www.friendsofpittville.org.uk April 2018 The aim of Friends of Pittville is to promote greater community involvement in the enjoyment, protection, future restoration and renewal of Pittville Park and Estate Welcome to the Friends of Pittville newsletter for ‘Working together with the Friends of Pittville, April 2018, delivered to every address in Pittville. and using the model of volunteering developed at Many thanks once again to the volunteer The Wilson, we will be working in the months distributors. ahead to take our efforts to the Pump Room, Read about our plant sale next month, the work where we are thrilled to be developing new roles being done on learning in the park and the for Volunteer Stewards and Guides to open up development of volunteer roles at the Pump and interpret this important building for Room. In a new feature focusing on people who Cheltenham residents and visitors. have become members of Friends of Pittville, ‘Do you have an interest in the history of Pittville member Andy Hopkins talks to FOP treasurer and enjoy working with the public? We want to Paul Benfield about what being a member of FOP hear from you! To register your interest in means to him. volunteering with us at the Pump Room, email [email protected] and play Volunteering at the Pump Room your part in making a vibrant and vital volunteer programme for the Pump Room a reality.’ Plant Sale To raise funds to help Friends of Pittville improve the Park Saturday 5 May 2018 10am to 1pm Central Cross Drive, Pittville GL52 2DX Register your interest if you would like to be considered for volunteering at the Pump Room. -

Form Studies

SIXTH Form Studies 1 9 DEAN 2 CLOSE 1 DC CHELTENHAM 0 0 SENIOR S CHOOL 2 2 Sixth Form Studies A LEVEL CHOICES AVAILABLE FOR STUDY Art & Design History Biology Latin Business Mathematics Chemistry Further Mathematics (15 periods) Classical Civilisation Further Mathematics (24 periods)* Computer Science Music Economics Physical Education Contact English Physics French Product Design Technology Registrar: Kelly Serjeant Geography Psychology [email protected] Government and Politics Religious Studies Greek Spanish *Counts as two A levels 2 | Sixth Form Studies 2019 ~ 2021 DEAN DC CLOSE CHELTENHAM SENIOR S CHOOL A word from Contents Page no. A Word from the Headmaster 3 the Headmaster Sixth Form Life 4 Personal Tutor 5 Co-Curricular Programme 6-7 “It’s very different, Sir” is the most common response that I get from Sixth Formers in answer to the question “How would you compare the What our students say 8 life of the Sixth Former to that of a member of Year 11?” A level Choices 9 How to choose A levels 10 It is different; deliberately and necessarily so. Our aim in the Sixth Form Results & Leavers Destinations 11 is to prepare pupils for life beyond School. For the vast majority this will mean being equipped with all the necessary skills and character Popular Degree Requirements 12 traits needed to flourish at university. For some it will mean being Flecker Library 13 launched into a specific vocation. Extended Project Qualification 14 In the classroom, the emphasis moves from the recall of facts to an Art & Design 16 added emphasis of judgement and analysis. -

Director of Music

Director of Music Recruitment Pack and Further Information DEAN DC CLOSE CHELTENHAM SENIOR S CHOOL DEAN DC CLOSE CHELTENHAM SENIOR S CHOOL Contents 1. Welcome from the Headmaster 2. The School 3. The Foundation 4. The Aims 5. Organisation Chart 6. Job Description 7. Location Welcome from the Headmaster Dean Close School is fortunate in so many ways. Its Dean Close’s Christian ethos informs much of what we do Cheltenham location places the School at the heart of a and reminds us of the intrinsic value of each individual and our beautiful town that is focused on learning and music through commitment to help them to flourish. This commitment has its great schools, festivals and accessibility to Birmingham, been at the heart of Helen Porter’s outstanding leadership of Bristol and Oxford. Situated on the edge of the Cotswolds, the Music Department. As Helen retires after 32 years at the just 5 minutes walk from the mainline railway station and 7 School, she leaves behind a community that is musically alive, minutes to the motorway, Dean Close is a great place to live a team of inspirational colleagues and an enviable local and and work. regional reputation for excellent musicianship. The School’s founders and successors have provided an Thank you for taking the time to look at this exciting role at outstanding site for a centre of education. With huge green Dean Close. I hope that your investigations leave you with a spaces and incredible facilities all located on 54 acres of strong sense of a school that is committed to the arts not only central Cheltenham, the diverse community of day pupils, for its own sake, but for society as a whole. -

Table 8 Maintenance Programme SUMMARY

Table 8 Maintenance Programme SUMMARY - Year 3-7 Total Cost to C Capital Total R Revenue Total General Fund Expenditure Code Building 2007/08 2008/09 2009/10 2010/11 2011/12 2007/08 2008/09 2009/10 2010/11 2011/12 PM0000 Contingency Fund - - - - - - - - - - - - - PM0000 Total - - - - - - - - - - - - - PM0010 Art Gallery/Museum 19,428 - 10,000 10,000 10,000 49,428 74,541 61,000 46,950 121,250 16,250 319,991 369,419 Clarence Street (51) - - - - - - 700 - - 800 - 1,500 1,500 Clarence Street (53) - - - - - - 326 - - 800 - 1,126 1,126 Clarence Street (55) - - - - - - 150 - - 800 - 950 950 Clarence Street Library 55,448 - - - - 55,448 19,454 69,000 25,700 90,700 1,200 206,054 261,502 PM0010 Total 74,876 - 10,000 10,000 10,000 104,876 95,171 130,000 72,650 214,350 17,450 529,621 634,497 PM0012 Clarence Street (51) - - - - - - - - 2,800 - 600 3,400 3,400 Clarence Street (53) - - - - - - - - 2,800 - 600 3,400 3,400 Clarence Street (55) - - - - - - - - 2,800 - 600 3,400 3,400 PM0012 Total - - - - - - - - 8,400 - 1,800 10,200 10,200 PM0020 Town Hall 215,231 35,000 346,250 85,000 59,000 740,481 80,601 113,000 130,300 79,300 92,800 496,001 1,236,482 PM0020 Total 215,231 35,000 346,250 85,000 59,000 740,481 80,601 113,000 130,300 79,300 92,800 496,001 1,236,482 PM0030 Pittville Pump Room 238,453 23,000 25,000 - - 286,453 39,763 165,650 185,300 87,300 62,800 540,813 827,266 PM0030 Total 238,453 23,000 25,000 - - 286,453 39,763 165,650 185,300 87,300 62,800 540,813 827,266 PM0040 Pittville Cricket Hall - - 15,000 - 15,000 30,000 2,666 - 4,650 3,150 7,351 -

RENOVATION of PITTVILLE PUMP ROOM and ITS REOPENING by Ashley Rossiter

Reprinted from Gloucestershire History No. 17 (2003) pages 16-20 RENOVATION OF PITTVILLE PUMP ROOM AND ITS REOPENING By Ashley Rossiter The Pittville Pump Room stands today as a the upper floor as officers’ accommodation. The monument of regency splendour, unquestionably Borough Surveyor was instructed by the Parks and one of Cheltenham’s most beautiful buildings. It was Recreation Grounds Committee to keep records of constructed between 1825-30 as the centrepiece of the condition of the building whilst it was in military what was supposed to be a magnificent estate hands. However, the military authorities during their financed by the minor local politician and occupation refused to allow periodical inspections speculative property developer Joseph Pitt.‘ In a and when eventually an inspection was allowed it town famous across England for its spa waters, was limited in its detail. His first report on the 9"‘ Pittville was the most ambitious and exclusive venue March 1942 noted that the surfacing in front of the for sampling the waters. It had been planned as a U- Pump Room was worn and in places was showing shape of Grecian villas with the Pump Room as its signs of disintegration. Also, the portico on each focal point, serving in its traditional role as a spa as side was walled in with brickwork to offer more well as a community centre. However as the 19th storage accommodation and some stone columns century continued the demand for spa water had been chipped at their bases from collision with decreased. The Pump Room no longer generated as the tailboards of lorries unloading supplies.7 At this much interest or revenue as in its heyday.