Work in Progress

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New College Library Archives and Manuscripts

New College Library Archives and Manuscripts Interim Handlist Collection reference MS CHA 3 Collection title Papers of Rev Dr Thomas Chalmers (1780-1846) Series Thomas Chalmers’ letters Shelfmark(s) MS CHA 3 1-28 About this handlist Scan of an older typescript list See also: MS CHA 1 Chalmers Family Documents MS CHA 2 Thomas Chalmers’ family letters MS CHA 4 Correspondence MS CHA 5 Special Collections eg Church Extension papers MS CHA 6 Manuscript writings and papers MS CHA 7 Photocopies of letters in the possession of Mrs Barbara Campbell MS CHA Appendix Boxes 1 to 11 New College Library MS CHA 3 Page 1 of 29 / MSS. CHA 301.1-640 1792-99. 1792 1795 J ames Cha1mers John Cha1mers I· ,/ ) 1793 1796 Wi11iam Chalmers 7 John Cha1mers 4 1794 1798 l.J i11iam Chalmers Dr. James Brown John Chalmers 11 Ma sonic Lodge of St. Vigeans 1799 Elizabeth Chalmers John Chalmers 12 New College Library MS CHA 3 Page 2 of 29 MSS .. CHA .3. 2.1-70. 1800-03. New College Library MS CHA 3 Page 3 of 29 MSS. 1803-08. 1803 1806 John Chalmers James Chalmers 2 William Sha\OT John Chalmers 1804 1807 James Chalmers 2 J ames Chalmers 5 ! John Chalmers 6 John Chalmers 6 1805 1808 J ames Chalmers James Chalmers 16 Jane Chalmers John Chalmers 4 New College Library MS CHA 3 Page 4 of 29 MSS. CHA 3.4.1-53. 1808-10. 1808 1810 James Chalmers 8 Andre1tl George Ca r stairs 2 John Chalmers 3 Elizabeth Cha1mers 2 J ames Chalmers 3 John Chalmers 4 1809 J am es Nairne James Chalmers John Chalmers E New College Library MS CHA 3 Page 5 of 29 MSS. -

The Hannay Family by Col. William Vanderpoel Hannay

THE HANNAY FAMILY BY COL. WILLIAM VANDERPOEL HANNAY AUS-RET LIFE MEMBER CLAN HANNAY SOCIETY AND MEMBER OF THE CLAN COUNCIL FOUNDER AND PAST PRESIDENT OF DUTCH SETTLERS SOCIETY OF ALBANY ALBANY COUNTY HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION COPYRIGHT, 1969, BY COL. WILLIAM VANDERPOEL HANNAY PORTIONS OF THIS WORK MAY BE REPRODUCED UPON REQUEST COMPILER OF THE BABCOCK FAMILY THE BURDICK FAMILY THE CRUICKSHANK FAMILY GENEALOGY OF THE HANNAY FAMILY THE JAYCOX FAMILY THE LA PAUGH FAMILY THE VANDERPOEL FAMILY THE VAN SLYCK FAMILY THE VANWIE FAMILY THE WELCH FAMILY THE WILSEY FAMILY THE JUDGE BRINKMAN PAPERS 3 PREFACE This record of the Hannay Family is a continuance and updating of my first book "Genealogy of the Hannay Family" published in 1913 as a youth of 17. It represents an intensive study, interrupted by World Wars I and II and now since my retirement from the Army, it has been full time. In my first book there were three points of dispair, all of which have now been resolved. (I) The name of the vessel in which Andrew Hannay came to America. (2) Locating the de scendants of the first son James and (3) The names of Andrew's forbears. It contained a record of Andrew Hannay and his de scendants, and information on the various branches in Scotland as found in the publications of the "Scottish Records Society", "Whose Who", "Burk's" and other authorities such as could be located in various libraries. Also brief records of several families of the name that we could not at that time identify. Since then there have been published two books on the family. -

<Ltnurnrbttt M4rulngtrul Jlnutijly

<ltnurnrbttt m4rulngtrul JlnutIJly Continuing LEHRE UNO VV EHRE I M AGAZIN FUER Ev.-LuTH. H OMILETIK I T H EOLOGICAL QUARTERLy-T HEOLOGICAL M ONTH LY Vol.L~ J une, 1949 No.6 CONTENTS Page De Opere Spiritus Sancti. L. B. Buchheimer .401 Thoma~ Guthrie. Apostle to the Slum".F. R. Webber 408 A Series of SermOli Studies for the Church Year 429 Miscellanea 441 Theological Observer 4GO Book Review ._. 478 Eln rcdlge- murJ nic.ht l1e1n wt<i Es isl kein Ding. daa die Idlute den. also dnss er dle Schafe unter mehr bel der Kirebe behaelt denn weise. wle sle rechte ChrIsten zollen die gute Predigt. - Apo!ogte, Art. 24 ~e1n . sondcm aueh dane ben den \Voel len w cliTen, dfl~' 5\(> die l:ic .ar} nJchl angre1fel\ una mit f llscher Lehre vcr If the tru""''let give an uncertain !uehren llfld Irrtum eln!u~hren. ~oWld . who shall prepare hlmself to Lu.thcT the battic? -1 C OT. 14. :8 Published by The Lutheran Church - Missouri Synod CONCORDIA. PUBLISHING BOUSE, St. Louis 18, Mo. I'UII'ftD Dr U. s .... Thomas Guthrie, Apostle to the Slums By F. R. WEBBER Everybody is aware that Dr. Thomas Guthrie was one of the most noted pulpit orators of the nineteenth century, but the fact is often overlooked that most of his long life was devoted to congregational work in the worst of Edinburgh's slums. He built a spacioul? church there and a parochial school; and in that district his well-known sermons were preached. They fill most of the sixteen volumes of his col lected works, and very few sermon books have enjoyed so large a circulation. -

John Mcleod Campbell and Thomas Erskine: Scottish Exponents of Righteousness, Faith, and the Atonement David P

Loma Linda University TheScholarsRepository@LLU: Digital Archive of Research, Scholarship & Creative Works Loma Linda University Electronic Theses, Dissertations & Projects 9-1985 John McLeod Campbell and Thomas Erskine: Scottish Exponents of Righteousness, Faith, and the Atonement David P. Duffie Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarsrepository.llu.edu/etd Part of the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Duffie, David P., "John McLeod Campbell and Thomas Erskine: Scottish Exponents of Righteousness, Faith, and the Atonement" (1985). Loma Linda University Electronic Theses, Dissertations & Projects. 421. http://scholarsrepository.llu.edu/etd/421 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by TheScholarsRepository@LLU: Digital Archive of Research, Scholarship & Creative Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Loma Linda University Electronic Theses, Dissertations & Projects by an authorized administrator of TheScholarsRepository@LLU: Digital Archive of Research, Scholarship & Creative Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UNIVERSITY 11131414WeN, LOMA Lliva)/11, CALIFORAITA LOMA LINDA UNIVERSITY Graduate School JOHN McLEOD CAMPBELL AND THOMAS ERSKINE: SCOTTISH EXPONENTS OF RIGHTEOUSNESS, FAITH, AND THE ATONEMENT by David P. Duffie A Thesis in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in Religion September 1985 © 1985 David P. Duffie All Rights Reserved 11 Each person whose signature appears below certifies that this thesis in his opinion is adequate, in scope and quality, as a thesis for the degree Master of Arts in Religion. , Chairman Dalton D. Baldwin, Professor of Christian Theology Paul . Landa rofessor of Church History a ,ztiL A. aham Maxwell, Professor of New Testament iii Abstract JOHN McLEOD CAMPBELL and THOMAS ERSKINE: SCOTTISH EXPONENTS OF RIGHTEOUSNESS, FAITH AND THE ATONEMENT by David P. -

The Bible and Creationism

University of Dayton eCommons English Faculty Publications Department of English 2017 The iB ble and Creationism Susan L. Trollinger University of Dayton, [email protected] William Vance Trollinger University of Dayton, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://ecommons.udayton.edu/eng_fac_pub Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, and the Christianity Commons eCommons Citation Trollinger, Susan L. and Trollinger, William Vance, "The iB ble and Creationism" (2017). English Faculty Publications. 105. http://ecommons.udayton.edu/eng_fac_pub/105 This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. 1 The Bible and Creationism Susan Trollinger and William Vance Trollinger, Jr. To understate the case, Charles Darwin’s Origin of Species (1859) marked a significant challenge to traditional understandings of the Bible and Christian theology. Darwin’s theory of organic evolution stood in sharp contrast with the Genesis account of creation, with its six days, separate creations of life forms, and special creation of human beings. More than this, Darwin’s ideas raised enormous theological questions about God’s role in creation (e.g., is there a role for God in organic evolution?) and about the nature of human beings (e.g., what does it mean to talk about original sin without a historic Adam and Eve?) Of course, what really made Darwin so challenging was that by the late nineteenth century his theory of organic evolution was the scientific consensus. -

Chapter One James Mylne: Early Life and Education

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: • This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. • A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. • This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. • The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. • When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. 2013 THESIS Rational Piety and Social Reform in Glasgow: The Life, Philosophy and Political Economy of James Mylne (1757-1839) By Stephen Cowley The University of Edinburgh For the degree of PhD © Stephen Cowley 2013 SOME QUOTES FROM JAMES MYLNE’S LECTURES “I have no objection to common sense, as long as it does not hinder investigation.” Lectures on Intellectual Philosophy “Hope never deserts the children of sorrow.” Lectures on the Existence and Attributes of God “The great mine from which all wealth is drawn is the intellect of man.” Lectures on Political Economy Page 2 Page 3 INFORMATION FOR EXAMINERS In addition to the thesis itself, I submit (a) transcriptions of four sets of student notes of Mylne’s lectures on moral philosophy; (b) one set of notes on political economy; and (c) collation of lectures on intellectual philosophy (i.e. -

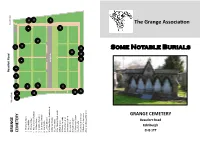

Some Notable Burials

Beaufort Road East Gate GRANGE West Gate 5 7 CEMETERY 1 2 3 4 6 8 1 Thomas Nelson 24 2 Hugh Miller 9 10 3 Thomas Oliver 4 Rev Thomas Chalmers 23 11 5 William Stuart 6 Charles MacLaren 22 12 7 Sir James Gowans 8 Ivan Szabo 9 James Moonie 28 10 William Stuart Cruickshank 13 11 Michael Taylor 12 James Smith 13 Sir Thomas Dick Lauder 14 Robin Cook 14 15 David Kennedy 21 16 Thomas Usher 17 Thomas Guthrie 18 James Thin 19 Andrew Usher 18 20 Alexander Cowan 20 21 John Usher 22 John Bartholomew 19 17 16 15 23 Robert Middlemass 24 Canon Edward Hannan Some Notable Burials Some Notable GRANGE CEMETERY The Grange Association Grange The Beaufort Road Beaufort Edinburgh EH9 1TT 24. Canon Edward Joseph Hannan (1836-1891) Canon Edward Joseph Hannan is known for his Grange Cemetery was established in 1847 by the Southern Cemetery Company Ltd. on involvement in the founding of Hibernian land donated by the Dick Lauder family of the Grange Estate. Designed by David Bryce, Football Club, ‘Hibs’. In the early 19th century the architect, the site occupied an open space of more than 12 acres and was built on a many Irish people migrated to Edinburgh, rectangular pattern around central vaulted catacombs which are built into the crest of living around the Cowgate, Grassmarket, West the hill. Bryce also designed the lodge, modified by J.G.Adams in 1890, and a mortuary Bow, Pleasance, Holyrood, St John's, West chapel which was never built. The cemetery lies on Beaufort Road and has been Port, Candlemaker's Row, Potterrow, expanded to Kilgraston Road. -

Science and the Scottish Evangelical Movement in Early Nineteenth Century Scotland: a Study in the Interactions of Science and Theology in the Work of the Rev

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 1989 Science and the Scottish evangelical movement in early nineteenth century Scotland: a study in the interactions of science and theology in the work of the Rev. Dr. Thomas Chalmers D.D., LL.D., 1780-1847 John E. Webster University of Wollongong Recommended Citation Webster, John E., Science and the Scottish evangelical movement in early nineteenth century Scotland: a study in the interactions of science and theology in the work of the Rev. Dr. Thomas Chalmers D.D., LL.D., 1780-1847, Master of Arts (Hons.) thesis, Department of Science and Technology Studies, University of Wollongong, 1989. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/2229 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] SCIENCE AND THE SCOTTISH EVANGELICAL MOVEMENT IN EARLY NINETEENTH CENTURY SCOTLAND A study in the interactions of science and theology in the work of the Rev. Dr. Thomas Chalmers D.D., LL.D., 1780-1847 A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree of MASTER OF ARTS (HONS.) from University of Wollongong by John E. Webster, B.A. (Wollongong) DEPARTMENT OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY STUDIES 1989 STATEMENT I hereby certify that the work contained in this thesis has not been submitted for a degree to any other university or institution. J.B. Webster DR. CH.ALMERS. TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION . 1 CHAPTER 1 The Scientific Interests of Chalmers' early years 15 2 Ordination and Call to Kilmany . -

Continuity and Discontinuity: the Lord's Supper in Historical

T Continuity and Discontinuity: The Lord’s Supper in Historical Perspective Henry Sefton A historical perspective on the Lord’s Supper as observed in Scotland shows continuities as well as discontinuities. The discontinuities are more obvious. John Knox acknowledged the important place which the Mass had occupied in religious life: I know that in the Mass hath not only been esteemed great holiness and honouring of God, but also the ground and foundation of our religion, so that, in the opinion of many, the Mass taken away, there resteth no true worshipping nor honouring of God in the earth.1 In spite of this Knox declared ‘that one Mass […] was more fearful to him than if ten thousand armed enemies were landed in any part of the realm, of purpose to suppress the whole religion.’2 The importance of the Mass derived from the fact that it was thought to occupy ‘the place of the last and mystical Supper of our Lord Jesus’; Knox’s aim was to prove that instead it was ‘idolatry before God, and blasphemous to the death and passion of Christ, and contrary to the Supper of Jesus Christ’.3 One must not conclude from statements like these that Knox undervalued the Lord’s Supper. On the contrary it has been pointed out by J. S. McEwen that Knox valued the Sacrament more than either Calvin or Luther: ‘None in the Reformed world made the Sacrament basic for the Church itself, as Knox did.’4 The observance of the Lord’s Supper as envisaged by Knox was very different from the ceremonies and context of the Mass. -

A Family Concern a History of the Indigent Old Women's Society 1797-2002 by Viviene E

Edinburgh Research Explorer A Family Concern Citation for published version: Cree, V 2005, A Family Concern: A History of the Indigent Old Women's Society, 1797-2002. University of Edinburgh. Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Publisher Rights Statement: © Cree, V.E. (2005) A Family Concern. A History of the Indigent Old Women's Society, 1797-2002, Edinburgh: The University of Edinburgh. General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 30. Sep. 2021 A Family Concern A History of the Indigent Old Women’s Society 1797-2002 By Viviene E. Cree The University of Edinburgh 7 Randolph Crescent, Edinburgh April 2005 Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................. 4 Acknowledgements ................................................................................................ -

Chalmers and Calvinism in 19Th Century Scotland

CALVIN REDISCOVERED: New Zealand and International Perspectives Knox Centre for Ministry and Leadership, August 23rd-25th, 2009. Thomas Chalmers and Scottish Calvinism in the 19th century John Roxborogh Thomas Chalmers (1780-1847)1 taught theology in Edinburgh from 1829 and was the first moderator of the Free Church of Scotland founded at the Disruption of 1843 when a third of the ministers and people left the Church of Scotland after a bitter ten year battle over the spiritual independence of the established church and the right of congregations to veto nominations to pulpits. A liberal evangelical famous for his parish experiment at St John’s in Glasgow from 1819 and the most celebrated preacher in Britain, Chalmers was a strong supporter of home and overseas missions and reinvigorated the ministry of elders, deacons and Sunday School teachers. His vision of a Godly commonwealth and a united mission inspired students who took his ideas around the world, including to New Zealand, where Port Chalmers is named after him. His attitude towards the Calvinism of his day, particularly as his theology developed after his conversion in 1811, is a window into a changing complex of Scottish ideas and traits which may be traced directly and indirectly to the Swiss reformer. Chalmers had some notable similarities to Calvin. Both were converted after a period seeking fame through academic publications and both came to live by their preaching and their writing. Chalmers too, no doubt modelled on Calvin, produced an Institutes of Christian Theology.2 Commentaries, correspondence and pastoral concern were features of both their ministries. -

Over the Years the Fife Family History Society Journal Has Reviewed Many Published Fife Family Histories

PUBLISHED FAMILY HISTORIES [Over the years The Fife Family History Society Journal has reviewed many published Fife family histories. We have gathered them all together here, and will add to the file as more become available. Many of the family histories are hard to find, but some are still available on the antiquarian market. Others are available as Print on Demand; while a few can be found as Google books] GUNDAROO (1972) By Errol Lea-Scarlett, tells the story of the settlement of the Township of Gundaroo in the centre of the Yass River Valley of NSW, AUS, and the families who built up the town. One was William Affleck (1836-1923) from West Wemyss, described as "Gundaroo's Man of Destiny." He was the son of Arthur Affleck, grocer at West Wemyss, and Ann Wishart, and encourged by letters from the latter's brother, John (Joseph Wiseman) Wishart, the family emigrated to NSW late in October 1854 in the ship, "Nabob," with their children, William and Mary, sole survivors of a family of 13, landing at Sydney on 15 February 1855. The above John Wishart, alias Joseph Wiseman, the son of a Fife merchant, had been convicted of forgery in 1839 and sentenced to 14 years transportation to NSW. On obtaining his ticket of leave in July 1846, he took the lease of the Old Harrow, in which he established a store - the "Caledonia" - and in 1850 added to it a horse-powered mill at Gundaroo some 18 months later. He was the founder of the family's fortunes, and from the 1860s until about 1900 the Afflecks owned most of the commercial buildings in the town.