Hilary Charlesworth and Judith Gardam

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell

Copyrights sought (Albert) Basil (Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell) Filson Young (Alexander) Forbes Hendry (Alexander) Frederick Whyte (Alfred Hubert) Roy Fedden (Alfred) Alistair Cooke (Alfred) Guy Garrod (Alfred) James Hawkey (Archibald) Berkeley Milne (Archibald) David Stirling (Archibald) Havergal Downes-Shaw (Arthur) Berriedale Keith (Arthur) Beverley Baxter (Arthur) Cecil Tyrrell Beck (Arthur) Clive Morrison-Bell (Arthur) Hugh (Elsdale) Molson (Arthur) Mervyn Stockwood (Arthur) Paul Boissier, Harrow Heraldry Committee & Harrow School (Arthur) Trevor Dawson (Arwyn) Lynn Ungoed-Thomas (Basil Arthur) John Peto (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin & New Statesman (Borlasse Elward) Wyndham Childs (Cecil Frederick) Nevil Macready (Cecil George) Graham Hayman (Charles Edward) Howard Vincent (Charles Henry) Collins Baker (Charles) Alexander Harris (Charles) Cyril Clarke (Charles) Edgar Wood (Charles) Edward Troup (Charles) Frederick (Howard) Gough (Charles) Michael Duff (Charles) Philip Fothergill (Charles) Philip Fothergill, Liberal National Organisation, N-E Warwickshire Liberal Association & Rt Hon Charles Albert McCurdy (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett & World Review of Reviews (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Colin) Mark Patrick (Crwfurd) Wilfrid Griffin Eady (Cyril) Berkeley Ormerod (Cyril) Desmond Keeling (Cyril) George Toogood (Cyril) Kenneth Bird (David) Euan Wallace (Davies) Evan Bedford (Denis Duncan) -

5830 the LONDON GAZETTE, 4 SEPTEMBER, 1925. Amounts of the Accepted Tenders Must Be Made Mr

5830 THE LONDON GAZETTE, 4 SEPTEMBER, 1925. amounts of the accepted Tenders must be made Mr. Colin Stratton Stratton-Hallett as Consul to the Bank of England by means of Cash or a of Austria at Plymouth; Banker's Draft on the Bank of England not Sir Eric Hutchison as Consul of Belgium at later than 2 o'clock (Saturday 12 o'clock) on Leith; the day on which the relative Bills or Bonds Mr. J. 0. Duncan as Consul of Austria at are to be dated. Dublin; 10. In virtue of the provisions of Section 1 Mr. J. 0. Duncan as Consul of Bolivia at (4) of the War Loan Act, 1919, Members of the Dublin; House of Commons are not precluded from Mr. Cornelius Ferris as Consul of the United tendering for these Bills and Bonds. States of America at Cobh, Queenstown; Signor Edoardo Pervan as Consul of Italy afa 11. Tenders must be made on the printed Calcutta; forms, which may be obtained from the Chief Monsieur E. Antoine as Consul of Belgium at Cashier's Office, Bank of England. Perth, for Western Australia; 12. The Lords Commissioners of His Senor Don Alfonso P. Cainisuli as Consul of Majesty's Treasury reserve the right of reject- the Dominican Republic at Georgetown; ing any Tenders. Senor Don Armando de Leon y Valdes as Treasury Chambers, Consul of Cuba at Kingstown, Jamaica; Mr. John Seymour Bonito as Consul of 4th September, 1925. Denmark at Accra, for the Gold Coast; Mr. Harry J. Anslinger as Consul of the United States of America at Nassau; Senor Don Alfredo Waldeman Kraft as Consul Foreign Office, of Bolivia at Port of Spain; 19th December, 1924. -

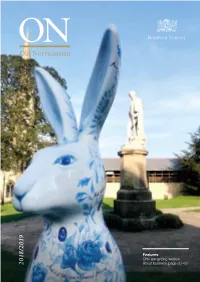

Old Norvicensian

ON Old Norvicensian Features 018/2019 ONs are getting serious 2 about business (page 20-43) 1 Old Norvicensian Welcome Welcome Welcome to this year’s edition of the or even reach out to acquaintances with Old Norvicensian magazine. As ever, it whom you have lost contact. seeks to provide a link with your school Contents by updating you on news from Cathedral Attending an ON event is always a good Close, both in terms of activities of the way to reconnect; please be in touch with current school and alumni events. the Development Team if you would like further details of what is coming up. You However, it also seeks to offer stimulation are guaranteed a warm welcome in School 02 94 114 and reflection from the ongoing lives of House, where my colleagues and I will Norvicensians in the wider world. After all, always be pleased to update you on the News & Announcements Obituaries our direct contact ends relatively early in latest news and plans. Updates Weddings, babies Remembering those ONs who your lives and the most we can do is set Development and and celebrations have sadly passed away you up for your ongoing experiences; most I should like to finish by offering my thanks School news of your life is lived as an Old Norvicensian to those who have worked hard to produce and, if we get it right, the best bits happen such a quality document – happy reading! then, too! Steffan Griffiths I therefore hope that the pages which Head Master follow will be of interest in their own right but will also encourage reflection on your own experiences from school and since 44 that time. -

The Schumacher Enigma

The Schumacher Enigma by Peter Etherden first published in February 1999 in Fourth World Review Number 93 To those who grew up in the alternative movement in the sixties and seventies, E.F. Schumacher is a giant. The institutions he worked to create in his lifetime...he died in 1977...such as the Soil Association and Intermediate Technology, have gone from strength to strength. Small is Beautiful has become one of the few canons of our generation. If not everybody has read it, everybody has accepted its ideas...and this is very unusual in these days of fragmentation and relativity. We are all Schumacherians now. We have Schumacher Societies, Schumacher Lectures... and even grand prix racing drivers named after him. Yet there is an enigma at the centre of The Schumacher Legend. Why did Schumacher show so little interest in money? Small is Beautiful is in four parts: I: The Modern World; II: Resources; III: The Third World and IV: Organisation and Ownership. Size has its own chapter: A Question of Size...the Leopold Kohr's influence; Land is there with its own chapter: The Proper Use of Land; Technology is there with its own chapter: Social and Economic Problems Calling for the Development of Intermediate Technology; Work is there; Education, Labour, Employment. Everything is there except money, income, wages and capital. Why? The two principal sources for Small is Beautiful were articles commissioned by the editor of Resurgence, John Papworth and speeches Schumacher gave in his capacity as chief economist for the National Coal Board...modified to some degree (in Part IV) by his involvement with Ernest Bader's small business and by Bader's rather idiosyncratic decision to put his company in a trust for the workers rather than allowing his son to inherit the firm. -

The Purpose of This Thesis Is to Trace Lady Katherine Grey's Family from Princess Mary Tudor to Algernon Seymour a Threefold A

ABSTRACT THE FAMILY OF LADY KATHERINE GREY 1509-1750 by Nancy Louise Ferrand The purpose of this thesis is to trace Lady Katherine Grey‘s family from Princess Mary Tudor to Algernon Seymour and to discuss aspects of their relationship toward the hereditary descent of the English crown. A threefold approach was employed: an examination of their personalities and careers, an investigation of their relationship to the succession problem. and an attempt to draw those elements together and to evaluate their importance in regard to the succession of the crown. The State Papers. chronicles. diaries, and the foreign correspondence of ambassadors constituted the most important sources drawn upon in this study. The study revealed that. according to English tradition, no woman from the royal family could marry a foreign prince and expect her descendants to claim the crown. Henry VIII realized this point when he excluded his sister Margaret from his will, as she had married James IV of Scotland and the Earl of Angus. At the same time he designated that the children of his younger sister Mary Nancy Louise Ferrand should inherit the crown if he left no heirs. Thus, legally had there been strong sentiment expressed for any of Katherine Grey's sons or descendants, they, instead of the Stuarts. could possibly have become Kings of England upon the basis of Henry VIII's and Edward VI's wills. That they were English rather than Scotch also enhanced their claims. THE FAMILY OF LADY KATHERINE GREY 1509-1750 BY Nancy Louise Ferrand A THESIS Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Department of History 1964 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am indebted to Dr. -

Tennis South Africa 2017/18 Annual Report (1St April 2017 – 31St March 2018)

00487 Tennis South Africa 2017/18 Annual Report (1st April 2017 – 31st March 2018) Tennis South Africa: 2017/18 Annual Report Page 1 of 52 1 Table of Contents. 03. The President’s summary of the year 14. The CEO’s report 18. Overview of our governance 21. Financial matters for the year 24. Departmental & affiliate reports 24. High Performance 26. Coaching 29. Development 31. Schools 34. Juniors, tournaments & new formats 37. Officiating 39. Seniors 43. Wheelchair Tennis SA 48. Transformation 51. Commercial partners Tennis South Africa: 2017/18 Annual Report Page 2 of 52 The President’s summary of the year INTRODUCTION: Kevin Anderson in action - on his way to the final of the 2017 US Open year. This report is presented at the end of a significantly more active and pleasing year for the National Federation. We have made progress in many areas. However there remain many mountains that need to be climbed to achieve our Mission Statement – “To enhance the quality of life for all South Africans of any age group, by growing the sport of tennis at every level, for everyone who wants to become involved”. Amongst the many milestones, local tennis has reached this last year, are the achievements of Kevin Anderson and Raven Klaasen on the international tour (Kevin progressed to the US Open Men’s Singles final in September – dare I mention his and Raven’s achievements at the 2018 Wimbledon Championship at this point as well), Phillip Henning’s reaching the fourth round of the 2018 Junior Australian Open in January, the promotion of our Davis Cup Team to the Euro Africa Group 1 division of the event and the promotion of our Federation Cup Team to Euro Africa Group 2. -

Water Plants of Sri Lanka, W. Henry De Thabrew, W. Vivian De Thabrew, Carol A

Water Plants of Sri Lanka, W. Henry De Thabrew, W. Vivian De Thabrew, Carol A. De Thabrew, 2010, 0946611203, 9780946611201 DOWNLOAD http://bit.ly/1SuirJo http://www.barnesandnoble.com/s/?store=book&keyword=Water+Plants+of+Sri+Lanka DOWNLOAD http://u.to/whozxL http://bit.ly/1z1Jp1V Aquatic plants of Australia a guide to the identification of the aquatic ferns and flowering plants of Australia, both native and naturalized, Helen Isobel Aston, 1973, Science, 368 pages. A Hand-book to the Flora of Ceylon: Containing Descriptions of All, Part 1 Containing Descriptions of All the Species of Flowering Plants Indigenous to the Island, and Notes on Their History, Distribution, and Uses, Henry Trimen, Arthur Hugh Garfit Alston, 1893, Botany, . The biology of weeds , Thomas Anthony Hill, 1977, Technology & Engineering, 64 pages. Pakistan Systematics, Volumes 1-2 , , 1977, Botany, . A Manual of Aquarium Plants , Shirley Aquatics, ltd, Colin D. Roe, 1960, Aquariums, 64 pages. Wild flowers of the Ceylon hills some familiar plants of the up-country districts, , 1953, Botany, 240 pages. Flowering plants of eastern India, Volume 1 , Jatindra Nath Mitra, 1958, Science, . Enumeratio plantarum Zeylaniæ an enumeration of Ceylon plants, with descriptions of the new and little-known genera and species, observations on their habitats, uses, native names, etc, George Henry Kendrick Thwaites, 1864, Botany, 483 pages. Aquarium plants and decoration , Robert F. O'Connell, 1973, Aquarium plants, 93 pages. Flora of Australia , , 2004, Science, 240 pages. Volume 56a of the highly acclaimed 'Flora of Australia' books covers some of the most spectacular and ecologically significant Australian lichens.. Records of the Botanical Survey of India, Volume 2 , , 1903, Botany, . -

The Breakdown of Nations Leopold Kohr

The Breakdown of Nations Leopold Kohr 1957, 1978 To Colin Lodge CONTENTS Acknowledgments Foreword by Kirkpatrick Sale Introduction I. The Philosophies of Misery II. The Power Theory of Aggression III. Disunion Now IV. Tyranny in a Small-State World V. The Physics of Politics: The Philosophic Argument VI. Individual and Average Man: The Political Argument VII. The Glory of the Small: The Cultural Argument VIII. The Efficiency of the Small: The Economic Argument IX. Union Through Division: The Administrative Argument X. The Elimination of Great Powers: Can it be Done? XI. But Will it be Done? XII. The American Empire? Afterword by the Author Appendices: The Principle of Federation Presented in Maps (Maps Drawn By Franc Riccardi) Bibliography Index ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Most of my inspiration I owe to friends whose love of challenge and debate was invaluable in the formulation of my ideas. This book would therefore never have been written without a long string of animated discussions with Diana Lodge, Anatol and Orlene Murad, Max and Isabel Gideonse, Sir Robert and Lady Fraser, my venerable late friend Professor George M. Wrong and Mrs. Wrong, Noel and Donovan Bartley Finn, my brother John R. Kohr, David and Manning Farrell, Franc and Rosemary Ricciardi, and, above all, Joan and Bob Alexander who for five long years had to bear with my constructions of pleasurable gloom at breakfast, lunch and dinner. Nor would the book ever have been published without the advice and encouragement of Sir Herbert Read, or without my friends and colleagues from the University of Puerto Rico—Severo Colberg, Adolfo Fortier, Hector Estades, Dean Hiram Cancio, and Chancellor Jaime Benitez—whose interest led to a gratefully acknowledged grant from the Carnegie Foundation. -

Of Armed Guerilla Fightng Against Portugese Rite in Mozambique, by the Liberation Front -FRELIMO

1ti, apartheid 1ti, apartheid OCTOBER 1969 PRCE fid MOZAMBIQUE HOTSPOT: BIG BUSINESS -CONFRONTS FREEDOM FIGHTERS Troullcd dam gets go-ahead TRECONTRAortheCaboaRessa"dantTe s ouorhwesin the contr n st montt b en the Portu-t l 0n e gut-e Gvèrnment and the International 4 gio, wok.... .... -isbY ,f Co etc,"n... ......na... v u vrum. espite optitic ptentatiena team the Poetuuese, the storm lauds are eiready Iookiag eminaue, and the ikeilhod of the peeject reahing maturity soema somewhet dtbious The dam ås duo to be iurlt in Tate prolce, where RELIMO guerilian hae been flghtlng for ove. n year, with cealderahibe uccess agatnst Portuguene soldier. FRELIMO in Weil awre et tho otgaifcaace of the dam, both'in terms of ntrengtheoing tho eonolomies o the white reglms in Southern AMrieo, and in terme ef ie effect on the Pe tUguese hold o ideaeebique. They have expressed their determination to otop tho dem being buit and the South A"etoa_ tro.ps that have moved into Tete era aleady coming under millttey presnure boeït FRtELIMO gflgter. Strntegists nee the tile l Tate an bing potéetiaiiy Sretal toaoheWhoie of tho nen - hot al. emady FRELIMO han establiohed lithented dm ne. ed ie odeaia, tholr tears lhnd eome hate. Mereover, they were eoncrood about the pe~ibility. ef reaking Swedish lama on ano toHns. Thre W.o litinly .ome confuion In the Swedish govermoett en this polnt S but Cahiart matin0 hed to di.cuss it g-nonced that ASEA would be runnlng the rink ot hehing the mm. Mreover, the FRELIMO reprentatie in Stookhim made it enar that ASEA would not b Obio to guarantee the peronal saety of any Swedish wores thnt mighl be mptoyed on the projeet. -

The Resurgence Story

The Resurgence Story First published in May 1966, Resurgence is the longest-running environmental magazine in Britain, closely followed by the Ecologist, which was founded in 1970. The titles merged in 2012. As the late David Nicholson-Lord, former Environment editor of the Independent on Sunday wrote: “That Resurgence has survived so long, without millionaire backing and without turning itself into a consumer lifestyle accessory, with the advertising to match, tells a compelling story – not only of conviction, commitment and endurance but of need, role and relevance.” Resurgence was founded in 1966 by John Papworth, a well-known peace campaigner with connections to the Committee of 100 and the Peace Pledge Union, but rapidly broadened its critique to encompass the nuclear nightmare generated by the Cold War, pollution, intensive farming and food production and the related political problems of centralisation, bigness and the growing separation of economics from ethics. Its presiding spirits in those early days included E F Schumacher, the “renegade economist” who wrote Small is Beautiful, and Leopold Kohr, the less famous but much-admired author of the decentralist classic The Breakdown of Nations. Both wrote frequently for Resurgence, as did the self-sufficiency guru John Seymour, but despite these and many other (voluntary) contributions, the magazine faced constant financial problems and in the early 1970s almost went bankrupt. In 1973, John Papworth left to take up a post with the Government of Zambia and a number of “guest editors” brought out different issues of the magazine, until Satish Kumar became editor in 1973. Remaining with Resurgence for the 43 years since, Satish is now editor-in-chief of the magazine. -

Seymour Rosofsky, Seymour Rosofsky, Hayden Herrera, Franz Schulze

Seymour Rosofsky, Seymour Rosofsky, Hayden Herrera, Franz Schulze DOWNLOAD http://bit.ly/1jo7Pze http://www.abebooks.com/servlet/SearchResults?sts=t&tn=Seymour+Rosofsky&x=51&y=16 DOWNLOAD http://u.to/BhWX5R http://www.fishpond.co.nz/Books/Seymour-Rosofsky http://bit.ly/1zg4hTd Suddenly, Seymour , Dennis L. Franks, Sep 1, 2006, Fiction, 108 pages. Seymour is an adulterous adventure cartoon about a contemporary little Asp with a winning smile. Typically, he also displays snakelike tantrums which flare from mild to wild. John Seymour , , , , . Listening to Stone The Art and Life of Isamu Noguchi, Hayden Herrera, Apr 21, 2015, Biography & Autobiography, 592 pages. From the author of Arshile Gorky, a major biography of the great American sculptor that redefines his legacy A master of what he called “the sculpturing of space,” Isamu. Rackstraw Downes recent work, 9 April - 3 May 1997, Rackstraw Downes, Hayden Herrera, Marlborough Gallery, 1997, , 41 pages. Mary Frank Sculpture/drawings/prints. [Exhibition] June 4 Through September 10, 1978, Mary Frank, Hayden Herrera, 1978, Sculpture, Modern, 62 pages. Chicago's Famous Buildings A Photographic Guide to the City's Architectural Landmarks and Other Notable Buildings, Franz Schulze, Kevin Harrington, 1993, Performing Arts, 337 pages. An updated edition of the classic guide to Chicago's architectural riches covers more than a decade of new architecture and looks back at the city's classical legacy of Adler. Frida A Biography of Frida Kahlo, Hayden Herrera, 1983, Biography & Autobiography, 507 pages. An in-depth biography of Mexican artist Frida Kahlo details her haunting and original painting style, her turbulent marriage to muralist Diego Rivera, her association with. -

Diversification and Intensification of Sources of Information for Young

.TF ION OF' QF NPQRrl/vr FOR VC)UNG IN — — — C) C) C) C) C) C) — — — SELF-Ew\LU,c\TIQI\J IREPDFtr OF IDRC PROJECT NC) .3— P —84—0324 CARRiED OUT flY INADES-FORMATION OFFICE, BAMRNDA, THE TECHN1CAIJ ASSISTANCE OF AJACA NJI (PhD), I)SCHANG tJNIVERSITY CENTRE, P.O. BOX 110 DSCHANG, (CAMEROON) PROJECT SNSORS I.D.R.C.,. CANADA EXECUTING AGENCY INADES-Formatlori (Cameroon) Bamenda Delegation PROJECT DURATION 2 YEARS (1986-1988) ARCHIV SEPTEMBER, 1980 56247 iDRO • Ub L I) I c!7VVICN l\t'Ji) IL IL P' IL II C)N C)F' oF' I 7\ IL i\1 (i)C)N — — — c, c, CL) c' c — — — —E\J/\LU/VJIC)NJ 1 C)F PR (L) -J F c; F I El) OUl' DV 1 NADES — FORMAT iON OFF iCE, I3ArIENDA, WI 1I I TIlE TECI IN I CAL ASS I OF AJAOI\ NJL (Ph.D), 1) DSCIIANO UNIVERSILY P.O. BOX 110 (CAIIEROON) PROJECt S1'01450R5 1.D.R.C., CANADA EXECUI1NO ACENCY Fotmatlort I'ROJECT DURATION 2 YEARS (1906-190D) SEPTEMBER. 191313 (' V C;c'2 T /\ E3 L E C) F C) NJ T E NJ T PART ONE Pages LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS, FIGURES AND TABLES — AUKNOWLEDCEMENTS iii EXECUTiVE SUMMARY 1 - 3 PART CHARACTERISTICS OF THE PROJECT 4 A A.l. Origins of the Project A.2. Location of the project - 6 BACKGROUND - 8 C. OF THE PROJECT 8 — 9 1). EXPECTED OUTPUTS 9 -10 10 I. Ultimate Beneficiaries 2. Ultimate Outcome 10 —12 LIODUS OPERANDI OF THE PROJECT 12 1.