Simon Morrison CV

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Prokofiev: Reflections on an Anniversary, and a Plea for a New

ИМТИ №16, 2017 Ключевые слова Прокофьев, критическое издание собрания сочинений, «Ромео и Джульетта», «Золушка», «Каменный цветок», «Вещи в себе», Восьмая соната для фортепиано, Янкелевич, Магритт, Кржижановский. Саймон Моррисон Прокофьев: размышления в связи с годовщиной и обоснование необходимости нового критического издания собрания сочинений Key Words Prokofiev, critical edition, Romeo and Juliet, Cinderella, The Stone Flower, Things in Themselves, Eighth Piano Sonata, Jankélévitch, Magritte, Krzhizhanovsky. Simon Morrison Prokofiev: Reflections on an Anniversary, And A Plea for a New Аннотация В настоящей статье рассматривается влияние цензуры на позднее Critical Edition советское творчество Прокофьева. В первой половине статьи речь идет об изменениях, которые Прокофьеву пришлось внести в свои балеты советского периода. Во второй половине я рассматриваю его малоизвестные, созданные еще до переезда в СССР «Вещи Abstract в себе» и показываю, какие общие выводы позволяют сделать This article looks at how censorship affected Prokofiev’s later Soviet эти две фортепианные пьесы относительно творческих уста- works and in certain instances concealed his creative intentions. In новок композитора. В этом контексте я обращаюсь также к его the first half I discuss the changes imposed on his three Soviet ballets; Восьмой фортепианной сонате. По моему убеждению, Прокофьев in the second half I consider his little-known, pre-Soviet Things in мыслил свою музыку как абстрактное, «чистое» искусство даже Themselves and what these two piano pieces reveal about his creative в тех случаях, когда связывал ее со словом и хореографией. Новое outlook in general. I also address his Eighth Piano Sonata in this критическое издание сочинений Прокофьева должно очистить context. Prokofiev, I argue, thought of his music as abstract, pure, even его творчество от наслоений, обусловленных цензурой, и выя- when he attached it to words and choreographies. -

Soviet Censorship Policy from a Musician's Perspective

The View from an Open Window: Soviet Censorship Policy from a Musician’s Perspective By Danica Wong David Brodbeck, Ph.D. Departments of Music and European Studies Jayne Lewis, Ph.D. Department of English A Thesis Submitted in Partial Completion of the Certification Requirements for the Honors Program of the School of Humanities University of California, Irvine 24 May 2019 i Table of Contents Acknowledgments ii Abstract iii Introduction 1 The Music of Dmitri Shostakovich 9 Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk District 10 The Fifth Symphony 17 The Music of Sergei Prokofiev 23 Alexander Nevsky 24 Zdravitsa 30 Shostakovich, Prokofiev, and The Crisis of 1948 35 Vano Muradeli and The Great Fellowship 35 The Zhdanov Affair 38 Conclusion 41 Bibliography 44 ii Acknowledgements While this world has been marked across time by the silenced and the silencers, there have always been and continue to be the supporters who work to help others achieve their dreams and communicate what they believe to be vital in their own lives. I am fortunate enough have a background and live in a place where my voice can be heard without much opposition, but this thesis could not have been completed without the immeasurable support I received from a variety of individuals and groups. First, I must extend my utmost gratitude to my primary advisor, Dr. David Brodbeck. I did not think that I would be able to find a humanities faculty member so in tune with both history and music, but to my great surprise and delight, I found the perfect advisor for my project. -

(With) Shakespeare (/783437/Show) (Pdf) Elizabeth (/783437/Pdf) Klett

11/19/2019 Borrowers and Lenders: The Journal of Shakespeare and Appropriation ISSN 1554-6985 V O L U M E X · N U M B E R 2 (/current) S P R I N G 2 0 1 7 (/previous) S h a k e s p e a r e a n d D a n c e E D I T E D B Y (/about) E l i z a b e t h K l e t t (/archive) C O N T E N T S Introduction: Dancing (With) Shakespeare (/783437/show) (pdf) Elizabeth (/783437/pdf) Klett "We'll measure them a measure, and be gone": Renaissance Dance Emily Practices and Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet (/783478/show) (pdf) Winerock (/783478/pdf) Creation Myths: Inspiration, Collaboration, and the Genesis of Amy Romeo and Juliet (/783458/show) (pdf) (/783458/pdf) Rodgers "A hall, a hall! Give room, and foot it, girls": Realizing the Dance Linda Scene in Romeo and Juliet on Film (/783440/show) (pdf) McJannet (/783440/pdf) Prokofiev’s Romeo and Juliet: Some Consequences of the “Happy Nona Ending” (/783442/show) (pdf) (/783442/pdf) Monahin Scotch Jig or Rope Dance? Choreographic Dramaturgy and Much Emma Ado About Nothing (/783439/show) (pdf) (/783439/pdf) Atwood A "Merry War": Synetic's Much Ado About Nothing and American Sheila T. Post-war Iconography (/783480/show) (pdf) (/783480/pdf) Cavanagh "Light your Cigarette with my Heart's Fire, My Love": Raunchy Madhavi Dances and a Golden-hearted Prostitute in Bhardwaj's Omkara Biswas (2006) (/783482/show) (pdf) (/783482/pdf) www.borrowers.uga.edu/7165/toc 1/2 11/19/2019 Borrowers and Lenders: The Journal of Shakespeare and Appropriation The Concord of This Discord: Adapting the Late Romances for Elizabeth the -

Steve Reich at 80: a Princeton Celebration

princeton.edu/music Monday, March 20, 2017 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT: Dasha Koltunyuk, [email protected], 609-258-6024 STEVE REICH AT 80: A PRINCETON CELEBRATION FEATURING A FREE PANEL DISCUSSION AND CONCERT BY SŌ PERCUSSION & GUESTS Sō Percussion, Princeton University’s Edward T. Cone Artists-in-Residence, will host a celebration—free and open to all—of iconic American composer Steve Reich on Tuesday, March 14, 2017 at Richardson Auditorium in Alexander Hall. The festivities will commence with a panel discussion at 4PM on Reich and his legacy, featuring conductor David Robertson, composer Julia Wolfe, and cellist Maya Beiser in conversation with musicology Professor Simon Morrison, and a second panel discussion at 5PM with Professor Morrison, composition Professor Donnacha Dennehy and Professor Steven Mackey in conversation with percussionist Adam Sliwinski of Sō Percussion. A mini-marathon concert, entitled Six Decades of Reich, will follow at 7:30PM, sampling works from each decade of the composer’s prolific career. Sō Percussion will be joined onstage by vocalist Beth Meyers, soprano Daisy Press, flutist Jessica Schmitz, pianists Orli Shaham and Corey Smythe, and cellist Maya Beiser. Ms. Beiser will perform Cello Counterpoint, written for her in 2003. The concert will culminate with Reich’s breakthrough masterpiece, Drumming, which Sō Percussion had performed at the Lincoln Center Festival this past fall to critical acclaim. Though admission for both the discussion and the concert are free, reservations are required for the concert. Please visit tickets.princeton.edu, or call the Frist Center Box Office at 609-258- 9220. “To hear [Sō Percussion], with their clarity and vivacity, in Mr. -

Behind the Scenes of the Fiery Angel: Prokofiev's Character

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by ASU Digital Repository Behind the Scenes of The Fiery Angel: Prokofiev's Character Reflected in the Opera by Vanja Nikolovski A Research Paper Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts Approved March 2018 by the Graduate Supervisory Committee: Brian DeMaris, Chair Jason Caslor James DeMars Dale Dreyfoos ARIZONA STATE UNIVERSITY May 2018 ABSTRACT It wasn’t long after the Chicago Opera Company postponed staging The Love for Three Oranges in December of 1919 that Prokofiev decided to create The Fiery Angel. In November of the same year he was reading Valery Bryusov’s novel, “The Fiery Angel.” At the same time he was establishing a closer relationship with his future wife, Lina Codina. For various reasons the composition of The Fiery Angel endured over many years. In April of 1920 at the Metropolitan Opera, none of his three operas - The Gambler, The Love for Three Oranges, and The Fiery Angel - were accepted for staging. He received no additional support from his colleagues Sergi Diaghilev, Igor Stravinsky, Vladimir Mayakovsky, and Pierre Souvchinsky, who did not care for the subject of Bryusov’s plot. Despite his unsuccessful attempts to have the work premiered, he continued working and moved from the U.S. to Europe, where he continued to compose, finishing the first edition of The Fiery Angel. He married Lina Codina in 1923. Several years later, while posing for portrait artist Anna Ostroumova-Lebedeva, the composer learned about the mysteries of a love triangle between Bryusov, Andrey Bely and Nina Petrovskaya. -

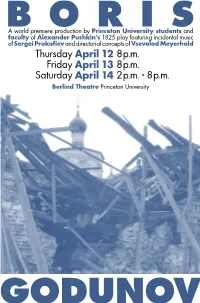

Program for the Production

BORISA world premiere production by Princeton University students and faculty of Alexander Pushkin’s 1825 play featuring incidental music of Sergei Prokofiev and directorial concepts of Vsevolod Meyerhold Thursday April 12 8 p.m. Friday April 13 8 p.m. Saturday April 14 2 p.m. † 8 p.m. Berlind Theatre Princeton University GODUNOV Sponsored by funding from Peter B. Lewis ’55 for the University Center for the Creative and Performing Arts with the Department of Music † Council of the Humanities † Edward T. Cone ’39 *43 Fund in the Humanities † Edward T. Cone ’39 *43 Fund in the Arts † Office of the Dean of the Faculty † Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures † School of Architecture † Program in Theater and Dance † Friends of the Princeton University Library and the Department of Rare Books and Special Collections † Alumni Council † Program in Russian and Eurasian Studies BORIS Simon Morrison † Caryl Emerson project managers Tim Vasen stage director Rebecca Lazier choreographer Michael Pratt † Richard Tang Yuk conductors Jesse Reiser † Students of the School of Architecture set designers Catherine Cann costume designer Matthew Frey lighting designer Michael Cadden dramaturg Peter Westergaard additional music Antony Wood translator Darryl Waskow technical coordinator Rory Kress Weisbord ’07 assistant director William Ellerbe ’08 assistant dramaturg Ilana Lucas ’07 assistant dramaturg Students of the Princeton University Program in Theater and Dance, Glee Club, and Orchestra GODUNOV Foreword I’m delighted to have the opportunity to welcome you to this performance of what has been, until now, a lost work of art, one now made manifest through a series of remarkable collaborations. -

Spring 2021 Nonfiction Rights Guide

Spring 2021 Nonfiction Rights Guide 19 West 21st St. Suite 501, New York, NY 10010 / Telephone: (212) 765-6900 / E-mail: [email protected] TABLE OF CONTENTS SCIENCE, BUSINESS & CURRENT AFFAIRS HOUSE OF STICKS THE BIG HURT BRAIN INFLAMMED HORSE GIRLS FIRST STEPS YOU HAD ME AT PET NAT RUNNER’S HIGH MY BODY TALENT MUHAMMAD, THE WORLD-CHANGER WINNING THE RIGHT GAME VIVIAN MAIER DEVELOPED SUPERSIGHT THE SUM OF TRIFLES THE KINGDOM OF CHARACTERS AUGUST WILSON WHO IS BLACK, AND WHY? CRYING IN THE BATHROOM PROJECT TOTAL RECALL I REGRET I AM ABLE TO ATTEND BLACK SKINHEAD REBEL TO AMERICA CHANGING GENDER KIKI MAN RAY EVER GREEN MURDER BOOK RADICAL RADIANCE DOT DOT DOT FREEDOM IS NOT ENOUGH HOW TO SAY BABYLON THE RISE OF THE MAMMALS THE RECKONING RECOVERY GUCCI TO GOATS TINDERBOX RHAPSODY AMERICAN RESISTANCE SWOLE APOCALYPSE ONBOARDING WEATHERING CONQUERING ALEXANDER VIRAL JUSTICE UNTITLED TOM SELLECK MEMOIR UNTITLED ON AI THE GLASS OF FASHION IT’S ALL TALK CHANGE BEGINS WITH A QUESTION UNTITLED ON CLASSICAL MUSIC MEMOIRS & BIOGRAPHIES STORIES I MIGHT REGRET TELLING YOU FIERCE POISE THE WIVES BEAUTIFUL THINGS PLEASE DON’T KILL MY BLACK SON PLEASE THE SPARE ROOM TANAQUIL NOTHING PERSONAL THE ROARING GIRL PROOF OF LIFE CITIZEN KIM BRAT DON’T THINK, DEAR TABLE OF CONTENTS, CONT. MINDFULNESS & SELF-HELP KILLING THATCHER EDITING MY EVERYTHING WE DON’T EVEN KNOW YOU ANYMORE SOUL THERAPY THE SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY OF GROWING YOUNG HISTORY TRUE AGE THE SECRETS OF SILENCE WILD MINDS THE SORCERER’S APPRENTICE INTELLIGENT LOVE THE POWER OF THE DOWNSTATE -

Diplomacy, Harnessing Classical Music for Power Purposes*

POLSKAAKADEMIANAUK KOMITET SOCJOLOGII INSTYTUT STUDIÓW POLITYCZNYCH 2017, nr 3 AUTOETNOGRAFIA MARZENNAJAMES PrincetonUniversity DIPLOMACY, HARNESSING CLASSICAL MUSIC FOR POWER PURPOSES* Lina and Serge by Simon Morrison is a rare bines a popular appeal of a compulsively read- phenomenon on the publishing market: it com- able biography with a valuable scholarly contri- Adres do korespondencji: mjames@prince *Simon Morrison, Lina and Serge: The Love and ton.edu Wars of Lina Prokofiev, Houghton Mifflin Har- 242 RECENZJE, OMÓWIENIA bution on a new research frontier in the study cabarets championing Russian music, would of history and politics—understanding the so- be enough material for a riveting biography. cial, economic and political realities underpin- However, Lina’s life took on an even more ning classical music in Soviet-style regimes. In extraordinary and, unfortunately, devastating particular, it reveals the staggering dimensions turn: the Prokofievs moved to the Soviet Uni- of the abuse of state power over composers and on in 1936. their families. Lina had met Serge in 1919 after one of At the heart of the attractiveness to the his performances. The virtuoso pianist, who ar- general public lies the dramatic life story of rived from Russia and toured the US, Europe, an amazing woman: Carolina (Lina) Prokofiev. and Japan, composed in his every spare mo- Brilliant, beautiful, and gifted with a captivating ment, including on train, ship, and during peri- sociability, she was born in 1898, to a Spanish- ods of respite afforded by periodical commis- -Russian-Polish family of excellent opera sing- sions from ballet and opera houses. The har- ers Juan Codina and Olga Nemisskaya. -

Hogg Proofs, PAGES

Critical Voices: The University of Guelph Book Review Project (Summer 2013) The People's Artist: Prokofiev's Soviet Years, by Simon Morrison. New York: Oxford University Press, 2009. [viii, 473 p., ISBN 9780195181678, $99.00] Pictures, play scripts, bibliography, glossary, index. Aldwyn A. Hogg, Jr. Second-year undergraduate (Bachelor of Arts, Honours (Music)) SOFAM, University of Guelph The twentieth-century was an era of artistic marvel and change. The arts, especially music, exploded and produced innumerable new styles and practices. It was a creative revolution. This revolution, however, was quashed in the newly founded nation of the USSR. Joseph Stalin, the leader of the soviet state, and his ideological followers mercilessly dissected the creative output of every composer in the USSR, forcing them to write in a manner that aligned with socialist philosophies. The People's Artist: Prokofiev's Soviet Years by Simon Morrison is an enthralling 363-page chronicle of the works composed by Sergey Prokofiev after his return to Soviet Russia and how he survived the impossible constraints of soviet musical culture— both as a composer and as an individual. !Morrison begins his scholarly monograph by tackling one of Prokofiev's most perplexing decisions—choosing to abandon Paris, France and return to the USSR. Prokofiev had taken up residence in the hub of musical and artistic development, France. Why then would he consider leaving, knowing the hardships faced by soviet composers? In short, Morrison convincingly shows Prokofiev was baited and lured to return by the Deputy People's Commissar for Foreign Affairs, Vladimir Potyomkin. In 1935, Soviet Russia was in dire need of internationally renowned artists and musicians to ameliorate its cultural standing in the world. -

Sergei Prokofiev's Semyon Kotko As a Representative Example of Socialist Realism

Simon Morrison Sergei Prokofiev's Semyon Kotko as a Representative Example of Socialist Realism Sergei Prokofiev composed his first Soviet opera, Semyon Kotko, in 1939, shortly after returning permanently to Soviet Russia from Europe. The libretto was taken from Valentin Katayev's 1938 novel Ya-si"n trudovogo naroda («l am a Son ofthe Working People»), a tale about the German invasion of a Ukrainian village during the post-revolutionary Civil War. Its highly didactic prose, reliance on description, and simplistic treatrnent of metaphor are typical features of so-called socialist realism, the official artistic doctrine of the Stalinist regime. In this essay I will examine the extent to which Prokofiev's opera does not uphold the tenets of this doctrine. While the deployment of musical ideas in the score generally follows the thematic development of Katayev's text, thus substantiating its political message, in several passages it can be argued that the music and text have contradictory meanings. In what follows, I suggest that Prokofiev establishes an authorial presence within the opera, thus challenging the conventions of socialist realism. Socialist Realism Although it has some connection to nineteenth century critical realism, socialist realism is most often described as a form of banal populism. lt emerged following the centralization and regimentation of the arts in the Soviet Union by Andrei Zhdanov, Stalin 's cultural comrnissar. The strict censures placed on Soviet artists led to a marked decline in the quality of the genre, with the utopian aesthetic of early examples of socialist real ist art transforming into «a materialized non-being» 1 in later examples. -

Behind the Scenes of the Fiery Angel: Prokofiev's Character

Behind the Scenes of The Fiery Angel: Prokofiev's Character Reflected in the Opera by Vanja Nikolovski A Research Paper Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts Approved March 2018 by the Graduate Supervisory Committee: Brian DeMaris, Chair Jason Caslor James DeMars Dale Dreyfoos ARIZONA STATE UNIVERSITY May 2018 ABSTRACT It wasn’t long after the Chicago Opera Company postponed staging The Love for Three Oranges in December of 1919 that Prokofiev decided to create The Fiery Angel. In November of the same year he was reading Valery Bryusov’s novel, “The Fiery Angel.” At the same time he was establishing a closer relationship with his future wife, Lina Codina. For various reasons the composition of The Fiery Angel endured over many years. In April of 1920 at the Metropolitan Opera, none of his three operas - The Gambler, The Love for Three Oranges, and The Fiery Angel - were accepted for staging. He received no additional support from his colleagues Sergi Diaghilev, Igor Stravinsky, Vladimir Mayakovsky, and Pierre Souvchinsky, who did not care for the subject of Bryusov’s plot. Despite his unsuccessful attempts to have the work premiered, he continued working and moved from the U.S. to Europe, where he continued to compose, finishing the first edition of The Fiery Angel. He married Lina Codina in 1923. Several years later, while posing for portrait artist Anna Ostroumova-Lebedeva, the composer learned about the mysteries of a love triangle between Bryusov, Andrey Bely and Nina Petrovskaya. It was then that Prokofiev’s characters took shape, reflecting the conflicting relationships in Bryusov’s real life and characters from the novel, as well as themes from Prokofiev’s own life. -

UMS in the Classroom

Arts in Context: UMS in the Classroom SUPPORTED BY THE ANDREW W. MELLON FOUNDATION Inon Barnatan by Marco Borggreve 2 UMS IN THE CLASSROOM 138TH SEASON 3 Welcome 49 M-Prize Winner: Calidore String Quartet Table of 4 Bringing Students to Performances 51 Budapest Festival Orchestra 7 Season Opening Event 53 Beyond Sacred: Voices of Muslim Identity, Ping Chong + Company 9 The TEAM: RoosevElvis 55 Jelly and George: Aaron Diehl and Contents 11 Kamasi Washington & The Next Step Cecile McLorin Salvant 13 Beethoven String Quartet Cycle, 57 Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra with Concerts 1 & 2: Takács Quartet Wynton Marsalis 15 Layla and Majnun, Mark Morris Dance Group / The 59 Druid: The Beauty Queen of Leenane Silk Road Ensemble 61 Beethoven’s Missa Solemnis: UMS Choral Union 17 Denis Matsuev, piano and Ann Arbor Symphony Orchestra 19 Dorrance Dance 63 Snarky Puppy 21 Berlin Philharmonic 65 Betroffenheit: Kidd Pivot and Electric Company Theatre 23 Gabrieli: A Venetian Coronation 1595 67 Steve Reich @ 80: Music for 18 Musicians, 25 Jake Shimabukuro eighth blackbird and Third Coast Percussion 27 Portrait of myself as my father, Nora Chipaumire 69 Mitsuko Uchida, piano 29 Handel’s Messiah: UMS Choral Union and 71 Beethoven String Quartet Cycle, Ann Arbor Symphony Orchestra Concerts 5 & 6: Takács Quartet 31 The King’s Singers: Christmas Songbook 73 DakhaBrakha 33 Last Work: Batsheva Dance Company 75 The Encounter: Complicite / Simon McBurney 35 Idiot-Syncrasy: Igor and Moreno 77 Michael Fabiano, tenor; Martin Katz, piano 37 Prague Philharmonia with