Iran and the Middle East After the Nuclear Agreement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

March 22, 2018 the Honorable John Kelly Chief of Staff White House

March 22, 2018 The Honorable John Kelly Chief of Staff White House 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue Washington, DC 20500 The Honorable John Sullivan Acting Secretary Department of State 2201 C St NW Washington, DC 20520 Dear General Kelly and Acting Secretary Sullivan, We, the undersigned Iranian-American organizations write with the utmost concern regarding the administration’s clear political and discriminatory targeting of civil servant Sahar Nowrouzzadeh. Career public servants are afforded protections against politically-motivated firings, and numerous protections have made it illegal for workers both inside and outside the government to be fired on behalf of their race, heritage, or religion. On March 15, 2018, the ranking members of the Committee on Oversight and Government Reform, Elijah Cummings, and House Foreign Affairs Committee, Eliot Engel, sent a letter on this subject to the White House Chief of Staff, General John F. Kelly, and the Deputy Secretary of State, John J. Sullivan. In their letter, they revealed receiving new documents indicating that “high level officials at the White House and State Department worked with a network of conservative activists to conduct a “cleaning” of employees…” including Ms. Nowrouzzadeh. Nowrouzzadeh is a distinguished Iranian American whose invaluable contributions to American national security led to her promotion to prominent positions in the White House, State Department, and Department of Defense. She served in both the George W. Bush and Obama administrations, thus demonstrating her proven track-record of adapting her work to the priorities of the sitting president, rather than any political party or preference. Given her prior experience and knowledge of Persian, she could have been an invaluable asset to the Trump administration. -

Cairo & Moscow Discuss Signing 4 Agreements on El Dabaa Nuclear

British Conservatives & US Republicans ask: The September 11 attacks: The truth An American- about the What a mess we got Israeli- Iranian lobby 6 ourselves into ? Iranian making 4 ESTABLISHED 1945 Economics is Geography has made us everywhere, and neighbors. History has understanding made us friends. Economics economics can has made us partners, and help you make necessity has made us better decisions allies. Those whom God and lead a has so joined together, happier life. let no man put asunder. Tyler Cowen / Themeobserver.com John F. Kennedy An American economist, academic & writer 35th President of the USA 1962 - Present / Themeobserver.com L.E 2.85 1917 - 1963 63 rd Year No. 19 www.meobserver.org Wednesday, 11 May 2016 News Cairo & Moscow discuss signing 4 in agreements on El Dabaa Nuclear Plant Numbers $308m EGP105m Egypt’s Orascom Egypt’s Palm Hills Egypt is to partake in the economic conference in St. Petersburg on June 16 Construction has Development Company’s won two contracts first-quarter net profit $31.4bn is the cost Cairo held preliminary talks with setting up the nuclear station with worth €270m dropped by more than Moscow over signing 4 executive Russian financing, which were ($307.75m) for work 40 per cent year-on- of Iraqi bombings agreements on Dabaa Nuclear signed in November 2015. By vir- on the third phase year to EGP105m, the Plant, and had other discussions tue of these two, 4 principle deals, of Cairo’s third real estate company with The Export-Import Bank of which are considered the green Dabaa metro rail line, it said in a bourse over 12 years Korea’s delegation on granting light to starting the project, were $3bn funds to implement several sealed. -

Iran's Nuclear Aspirations: a Threat to Regional Stability by Ronni Naggar a THESIS Submitted to Oregon State University Honor

Iran’s Nuclear Aspirations: A Threat to Regional Stability by Ronni Naggar A THESIS submitted to Oregon State University Honors College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Honors Baccalaureate of Arts in Political Science (Honors Associate) Presented November 26, 2019 Commencement June 2020 10 11 AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Ronni Naggar for the degree of Honors Baccalaureate of Arts in Political Science presented on November 26, 2019. Title: Iran’s Nuclear Aspirations: A Threat to Regional Stability Abstract approved:_____________________________________________________ Jonathan Katz This thesis examines the multi-faceted threat Iran poses to the stability of the Middle Eastern region, to U.S. geopolitical interests and to the furthering of democratic principles from a realist perspective. Iran’s failure to negotiate a nuclear accord in good faith coupled with its continued militant role in regional affairs are indicators of future escalating tensions. I weigh the viewpoints of both proponents and skeptics regarding the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) and examine controversies surrounding this accord. My approach is informed by an interview with Lily Ranjbar, an Iranian nuclear scientist currently residing in the United States, and the insights of political scientists Paasha Mahdavi and Michael Ross on the relationship between oil wealth and the adverse effects this has on civil liberties and democracy. I further support my hypothesis through the application of theories developed by economists Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson who have studied the dynamics of extractive institutions in certain regions, including the Middle East. As this thesis demonstrates, the divisiveness promoted by Iran in order to establish itself as a regional power offers an illustration of the Thucydides theory. -

The New Yorker Crossword Puzzle Jill Lepore (“Sirens in the Night,” P

MAY 21, 2018 9 GOINGS ON ABOUT TOWN 33 THE TALK OF THE TOWN Robin Wright on Trump’s Iran-deal outrage; the N.R.A. Hulk; the Duplass brothers; techno Germans; Carol Burnett’s youngest fans. ANNALS OF GAMING Nick Paumgarten 40 Weaponized The latest teen video-game craze. SHOUTS & MURMURS Josh Gondelman 46 Recommendations AMERICAN CHRONICLES Jill Lepore 48 Sirens in the Night Do victims’ rights harm justice? THE POLITICAL SCENE Evan Osnos 56 Only the Best People Trump’s government purge. LETTER FROM CALIFORNIA Adam Gopnik 66 Bottled Dreams The quest to make a truly American wine. FICTION John L’Heureux 74 “The Long Black Line” THE CRITICS BOOKS Lauren Collins 82 A reading list for the royal wedding. 86 Briefly Noted Tobi Haslett 89 Alain Locke, dean of the Harlem Renaissance. MUSICAL EVENTS Alex Ross 94 Harpsichord smackdown! POP MUSIC Amanda Petrusich 96 Courtney Barnett’s laid-back angst. THE CURRENT CINEMA Anthony Lane 98 “First Reformed,” “The Seagull.” POEMS Cynthia Zarin 62 “Marina” Peter Cooley 79 “Bear” COVER John Cuneo “The Swamp” DRAWINGS Mick Stevens, Edward Steed, Seth Fleishman, Pia Guerra, P. C. Vey, Liana Finck, Will McPhail, Harry Bliss, Roz Chast, Carolita Johnson, Frank Cotham, Maddie Dai, David Sipress, Bruce Eric Kaplan, Lars Kenseth, Jon Adams SPOTS Serge Bloch Introducing CONTRIBUTORS The New Yorker Crossword Puzzle Jill Lepore (“Sirens in the Night,” p. 48) Evan Osnos (“Only the Best People,” is a professor of history at Harvard. p. 56) writes about politics and foreign Her new book, “These Truths: A His- afairs for the magazine. -

House of Bribes

1 House of Bribes: How the United States led the way to a Nuclear Iran October 2015 2 House of Bribes: How the United States Led the Way to a Nuclear Iran is a product of the New Coalition of Concerned Citizens: Adina Kutnicki Andrea Shea King Dr. Ashraf Ramelah Benjamin Smith Brent Parrish Charles Ortel Denise Simon Dick Manasseri Gary Kubiak Hannah Szenes Right Side News Marcus Kohan General Paul E. Vallely Regina Thomson Scott Smith Terresa Monroe-Hamilton Colonel Thomas Snodgrass Trevor Loudon Wallace Bruschweiler William Palumbo 3 Contents Executive Summary ....................................................................................................................................................5 Preface ........................................................................................................................................................................5 Background .................................................................................................................................................................5 The Trailblazers: Namazi & Nemazee .........................................................................................................................6 National Iranian-American Council (NIAC) .................................................................................................................8 The Open (Iranian) Society of George Soros ........................................................................................................... 11 Valerie Jarrett – The -

Iranian American Organizations Call for Independent Investigation For

Seven Iranian American Organizations Call for an Independent Investigation into the Discriminatory Treatment of Iranian-American Civil Servant, Sahar Nowrouzzadeh Dear Members and Friends, Several prominent Iranian American organizations united to call for an independent investigation into the discriminatory targeting of an Iranian American civil servant, Sahar Nowrouzzadeh. After she was prematurely reassigned from the State Department's Policy Planning Staff, documentation reported by Politico revealed that her reassignment was at least in part due to questions about her political loyalty and where she was born. This information was so concerning that ranking members of the House Foreign Affairs and Oversight Committees have written the administration to demand answers. The letter of the Iranian American organizations follows: "The Honorable John Kelly Chief of Staff White House 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue Washington, DC 20500 The Honorable John Sullivan Acting Secretary Department of State 2201 C St NW Washington, DC 20520 Dear General Kelly and Acting Secretary Sullivan, We, the undersigned Iranian-American organizations write with the utmost concern regarding the administration's clear political and discriminatory targeting of civil servant Sahar Nowrouzzadeh. Career public servants are afforded protections against politically-motivated firings, and numerous protections have made it illegal for workers both inside and outside the government to be fired on behalf of their race, heritage, or religion. On March 15, 2018, the ranking members of the Committee on Oversight and Government Reform, Elijah Cummings, and House Foreign Affairs Committee, Eliot Engel, sent a letter on this subject to the White House Chief of Staff, General John F. Kelly, and the Deputy Secretary of State, John J. -

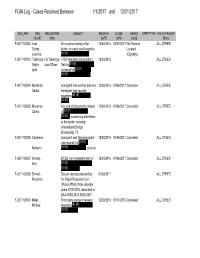

Department of State FOIA Log 2017

FOIA Log - Cases Received Between 1/1/2017 and 12/31/2017 REQ_REF REQ REQUESTER SUBJECT RECEIVE CLOSE GRANT EXEMPTIONS FEE CATEGORY NAME ORG DATE DATE CODE DESC F-2017-00002 Leal All records relating to the 12/30/2016 02/27/2017 No Records ALL OTHER Oteiza, border crossing card issued to Located Lourdes (b) (6) . (Oglesby) F-2017-00003 Tabangay-Fel Tabangay I-130 immigrant visa petition 12/30/2016 ALL OTHER Vigilla, Law Offices filed by (b) (6) April on behalf of (b) (6) (b) (6) F-2017-00004 Monarrez, Immigrant visa petition and non- 12/30/2016 01/06/2017 Cancelled ALL OTHER Carlos immigrant visa records regarding (b) (6) (b) (6) F-2017-00005 Monarrez, Any and all documents related 12/30/2016 01/06/2017 Cancelled ALL OTHER Carlos to (b) (6) (b) (6) concerning detentions at the border crossing International Bridge Brownsville, TX F-2017-00006 Cardenas Immigrant and Non-immigrant 12/30/2016 01/06/2017 Cancelled ALL OTHER , visa records for (b) (6) Norberto (b) (6) records F-2017-00007 Arocha, B1/B2 non-immigrant visa for 12/30/2016 01/06/2017 Cancelled ALL OTHER Ana (b) (6) (b) (6) F-2017-00008 Emmel, Special reports produced by 01/03/2017 ALL OTHER Benjamin the Rapid Response Unit (Public Affairs) from calendar years 2015-2016, described in DAA-0059-2013-0008-0001 F-2017-00010 Miller, Third party passport request 12/29/2016 01/17/2018 Cancelled ALL OTHER Michael regarding (b) (6) (b) (6) REQ_REF REQ REQUESTER SUBJECT RECEIVE CLOSE GRANT EXEMPTIONS FEE CATEGORY NAME ORG DATE DATE CODE DESC F-2017-00011 Cabrera, Cables, files, and documents -

PRINCE-DOCUMENT-2018.Pdf

A Theoretical Analysis of the Capability of the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps and Its Surrogates to Conduct Covert or Terrorist Operations in the Western Hemisphere. The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Prince, William F. 2018. A Theoretical Analysis of the Capability of the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps and Its Surrogates to Conduct Covert or Terrorist Operations in the Western Hemisphere.. Master's thesis, Harvard Extension School. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:42004011 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA A Theoretical Analysis of the Capability of the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps and Its Surrogates to Conduct Covert or Terrorist Operations in the Western Hemisphere. William F. Prince A Thesis in the Field of International Relations For the Master of Liberal Arts in Extension Studies Harvard University May 2018 Copyright 2018 William F. Prince Abstract The Islamic Republic of Iran is one of only three state sponsors of terrorism as designated by the U.S. Department of State. The basic goal of this project has been to determine what capability the Islamic Republic has to conduct covert or terrorist operations in the Western Hemisphere. Relevant background to this research puzzle essentially begins with the 1979 Iranian Revolution and the subsequent taking of U.S. -

U.S. Foreign Policy Towards Saudi Arabia How the Islamic Revolution Has Changed U.S.- Saudi Arabian Relations

U.S. Foreign Policy towards Saudi Arabia How the Islamic Revolution has changed U.S.- Saudi Arabian relations. Adaja Klijnstra s1041168 BA Thesis, pre-master North American Studies, 2019-2020 Faculty of Arts, Radboud University Nijmegen Supervisor: Dr Peter van der Heiden Second reader: Dr Albertine Bloemendal Klijnstra (s1041168) /1 Pre-Master North American Studies – Faculty of Arts Teachers who will receive this document: Dr Peter van der Heiden, Dr Albertine Bloemendal Title of document: U.S. Foreign Policy towards Saudi Arabia: How the Islamic Revolution has changed U.S.-Saudi Arabian relations. Name of course: BA Thesis Date of submission: 2 July 2020 The work submitted here is the sole responsibility of the undersigned, who has neither committed plagiarism nor colluded in its production. Signed Name of student: Adaja Klijnstra Student number: 1041168 Klijnstra (s1041168) /2 Abstract This thesis examines the political relationship between the United States and the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, whose ‘special friendship’ has arguably been crucial in the shaping of the cultural and political landscape of the Middle East. We will look into how the increasingly strained relationship between the United States and Saudi Arabia has continued to develop until the present day by arguing that this may be due to notions of global and regional exceptionality on the parts of Washington and Riyadh respectively. This thesis serves as a guide that examines how U.S.-Saudi political relations changed after the Islamic revolution in Iran by comparing the state of U.S.-Saudi relations before and after 1979. Ultimately, this comparison will lead to a conclusion that explains to what extent the relationship between the two states has been altered. -

US Foreign Policy in the Middle East: Changes in the Neoliberal Age

US Foreign Policy in the Middle East: Changes in the Neoliberal Age U.S. Foreign Policy in the Middle East: Changes in the Neoliberal Age UCLA Luskin Center for History and Policy Featuring articles by Mariam Aref, Leila Achtoun, Jessica Brouard, and Karina Ourfalian With an introduction edited by Firyal Bawab Edited and compiled by Philip Hoffman, Lily Hindy, and Monica Widmann June 2021 Preface The Middle East Research Initiative (MERI) that produced this collection originated in a series of meetings in late 2019 and early 2020. We started as a group of undergraduates and two graduate student coordinators, joined together by the broad goal of examining the long-term drivers and effects (both domestically and internationally) of American foreign policy in the Middle East. In our first planning documents, we hoped to produce several case studies and a collaborative theoretical piece over the course of a year--ambitions that seemed relatively modest at the time. We put out a call for interested students and attracted a range of undergraduates from different disciplines. Shortly after our first group meeting, however, the COVID-19 pandemic threatened to upend our plans. Travel for archival research became impossible and collaborative work over Zoom posed challenges. Nevertheless, the undergraduate members of MERI showed an impressive work ethic and persisted, producing insightful and rigorous essays on a range of topics. Rather than shy away from issues raised by the pandemic, they addressed them directly. At its heart, our volume, which is devoted to “U.S. Middle East Policy in the Neoliberal Age,” describes international and domestic manifestations of the forces of austerity and privatization. -

List Amir Handjani Amir Handjani Is an Energy Lawyer and Senior Advisor at KARV Communications, a Strategic Communications and Public Affairs Firm

Alison Friedman Alison Kiehl Friedman is Executive Director of the International Corporate Accountability Roundtable, and a longtime activist on human trafficking. She served as Deputy Director in the State Department’s Office to Monitor and Combat Trafficking in Persons in the Obama administration, where she managed over $50 million in federal grants and US interagency processes to combat human trafficking. She previously co-founded ASSET, an organization that addressed human trafficking in global supply chains, where she helped author the California Transparency in Supply Chains law. She also previously worked for California Representative Jane Harman, where she managed security and transportation challenges around major ports and LAX. Friedman holds a B.A. from Stanford University. Education: B.A., Political Science and Government, Stanford University, 2002; M.B.A., Oxford University, Saïd Business School, 2017 Affiliations: US House of Representatives, Office of Jane Harman (District Director) US Department of State, Office to Monitor and Combat Trafficking in Persons (Deputy Director) International Corporate Accountability Roundtable (Executive Director) Free the Slaves (Interim Executive Director) The Global Fund to End Slavery (Vice President) Alliance to Stop Slavery and End Trafficking (Executive Director) People for the American Way (San Francisco Office Director, California Policy Director, Legislative Coordinator) Gore/Lieberman 2000 (National Student Director) Key Publications: Thompson Reuters Foundation News, "Trump does -

Belfer Center Fellows and Visiting Scholars 2020–2021 TABLE of CONTENTS

BELFER CENTER ORIENTATION | SEPTEMBER 11, 2020 Belfer Center Fellows and Visiting Scholars 2020–2021 TABLE OF CONTENTS Core Fellows Cyber Project Economic Diplomacy Initiative Sasha Baker .................................2 Justin Key Canfil ...................... 46 Vincent Brooks ...........................2 Naniette Coleman ................... 46 Christopher Li ...........................78 Morgan Brown ............................4 Amanda Current ......................47 Joshua Lipsky ...........................78 Tom Donilon ................................4 Amy Ertan ..................................47 Joseph F. Dunford, Jr. ...............6 Gregory Falco .......................... 48 Environment and Natural Michèle Flournoy........................7 Jeffrey Fields ............................ 49 Resources Program Benjamin Heineman ..................9 Robert Knake ........................... 49 Bo Bai .......................................... 81 Karen Elliott House .................. 10 Priscilla Moriuchi ..................... 50 Jing Chen ................................... 81 Syra Madad ..................................11 Nand Mulchandani .................. 50 Marinella Davide....................... 81 Susan Rice...................................12 Bruce Schneier ..........................51 Nicola de Blasio ........................82 Lori Robinson ............................ 14 Anina Schwarzenbach ............52 Alejandro Nunez-Jimenez .... 84 Sarah Sewall ...............................15 Camille Stewart ........................52