Sample Pages

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Robert Burns Fellowship 2020

THE ROBERT BURNS FELLOWSHIP 2020 The Fellowship was established in 1958 by a group of citizens, who wished to remain anonymous, to commemorate the bicentenary of the birth of Robert Burns and to perpetuate appreciation of the valuable services rendered to the early settlement of Otago by the Burns family. The general purpose of the Fellowship is to encourage and promote imaginative New Zealand literature and to associate writers thereof with the University. It is attached to the Department of English and Linguistics of the University. CONDITIONS OF AWARD 1. The Fellowship shall be open to writers of imaginative literature, including poetry, drama, fiction, autobiography, biography, essays or literary criticism, who are normally resident in New Zealand or who, for the time being, are residing overseas and who in the opinion of the Selection Committee have established by published work or otherwise that they are a serious writer likely to continue writing and to benefit from the Fellowship. 2. Applicants for the Fellowship need not possess a university degree or diploma or any other educational or professional qualification nor belong to any association or organisation of writers. As between candidates of comparable merit, preference shall be given to applicants under forty years of age at the time of selection. The Fellowship shall not normally be awarded to a person who is a full time teacher at any University. 3. Normally one Fellowship shall be awarded annually and normally for a term of one year, but may be awarded for a shorter period. The Fellowship may be extended for a further term of up to one year, provided that no Fellow shall hold the Fellowship for more than two years continuously. -

Manifesto Aotearoa

Manifesto Aotearoa NEW TITLE 101 political poems INFORMATION OTAGO Eds Philip Temple & Emma Neale UNIVERSITY • Explosive new poems for election year from David Eggleton, Cilla McQueen, Vincent PRESS O’Sullivan, Tusiata Avia, Frankie McMillan, Brian Turner, Paula Green, Ian Wedde, Vaughan Rapatahana, Ria Masae, Peter Bland, Louise Wallace, PUBLICATION DETAILS Bernadette Hall, Airini Beautrais and 84 others… Manifesto Aotearoa • Original artwork by Nigel Brown 101 political poems Eds Philip Temple & Emma Neale A poem is a vote. It chooses freedom of imagination, freedom of critical thought, freedom of speech. Otago University Press A collection of political poems in its very essence argues for the power of the democratic voice. www.otago.ac.nz/press Here New Zealand poets from diverse cultures, young and old, new and seasoned, from Poetry the Bay of Islands to Bluff, rally for justice on everything from a degraded environment to hardback with ribbon systemically embedded poverty; from the long, painful legacy of colonialism to explosive issues 230 x 150 mm, 184 pp approx. of sexual consent. ISBN 978-0-947522-46-9, $35 Communally these writers show that political poems can be the most vivid and eloquent calls for empathy, for action and revolution, even for a simple calling to account. American poet Mark Leidner tweeted in mid-2016 that ‘A vote is a prayer with no poetry’. IN-STORE: APR 2017 Here, then, are 101 secular prayers to take to the ballot box in an election year. But we think this See below for ordering information book will continue to express the nation’s hopes every political cycle: the hope for equality and justice. -

Ka Mate Ka Ora: a New Zealand Journal of Poetry and Poetics

ka mate ka ora: a new zealand journal of poetry and poetics Issue 4 September 2007 Poetry at Auckland University Press Elizabeth Caffin Weathers on this shore want sorts of words. (Kendrick Smithyman, ‘Site’) Auckland University Press might never have been a publisher of poetry were it not for Kendrick Smithyman. It was his decision. As Dennis McEldowney recalls, a letter from Smithyman on 31 March 1967 offering the manuscript of Flying to Palmerston, pointed out that ‘it is to the university presses the responsibility is falling for publishing poetry. Pigheaded and inclined to the parish pump, I would rather have it appear in New Zealand if it appears anywhere’.1 Dennis, who became Editor of University Publications in 1966 and in the next two decades created a small but perfectly formed university press, claimed he lacked confidence in judging poetry. But Kendrick and C. K. Stead, poets and academics both, became his advisors and he very quickly established an impressive list. At its core were the great New Zealand modernist poets. Dennis published five books by Smithyman, three by Stead and three by Curnow starting with the marvellous An Incorrigible Music in 1979.2 Curnow and Smithyman were not young and had published extensively elsewhere but most would agree that their greatest work was written in their later years; and AUP published it. Soon a further group of established poets was added: three books by Elizabeth Smither, one by Albert Wendt, one by Kevin Ireland. And then a new generation, the exuberant poets of the 1960s and 1970s such as Ian Wedde (four books), Bill Manhire, Bob Orr, Keri Hulme, Graham Lindsay, Michael Harlow. -

Newsletter – 21 November 2011 ISSN: 1178-9441

INTERNATIONAL INSTITUTE OF MODERN LETTERS Te P¯utahi Tuhi Auaha o te Ao Newsletter – 21 November 2011 ISSN: 1178-9441 This is the 175th in a series of occasional newsletters from the Victoria University centre of the International Institute of Modern Letters. For more information about any of the items, please email modernletters. 1. A real e-book ........................................................................................................... 1 2. Making Baby Float ................................................................................................. 2 3. Bernard Beckett ....................................................................................................... 2 4. A possible Janet Frame sighting? ........................................................................... 2 5. A poetry masterclass ................................................................................................ 3 6. Awards and prizes ................................................................................................... 3 7. Eric Olsen meets the muse ..................................................................................... 3 8. The expanding bookshelf......................................................................................... 4 9. Best New Zealand Poems ....................................................................................... 4 10. Peter Campbell RIP ............................................................................................. 4 11. Gossipy bits ........................................................................................................... -

July-October Funding Round 2005

Creative New Zealand Grants JULY - OCTOBER FUNDING ROUND 2005/2006 This is a complete list of project grants offered in the first funding round of the 2005/2006 financial year. Applications to this round closed on 29 July 2005 and grants were announced in late October. Grants are listed within artforms under Creative New Zealand funding programmes. In this round, 264 project grants totalling more than $3.8 million were offered to artists and arts organisations. Approximately $13.8 million was requested from 784 applications. Arts Board: Creative and FINE ARTS Peppercorn Press: towards publishing five issues of “New Zealand Books” Professional Aotearoa Digital Arts and Caroline McCaw: $27,000 towards the third annual symposium Development $10,000 Takahe Collective Trust: towards publishing CRAF T/OBJECT ART three issues of “Takahe” Dunedin Public Art Gallery: towards David Bennewith: towards study in the $12,000 international exhibition research Netherlands $11,420 $8000 The New Zealand Poetry Society Inc: towards its annual programme of activities The Imaginary Partnership: towards two issues of Audrey Boyle: to participate in the Craft $15,000 “Illusions” magazine Victoria “Common Goods” residency $10,000 programme The New Zealand Poetry Society Inc: towards $3360 two Poets in Workplaces residencies Hye Rim Lee: towards a residency in Korea $6500 $7500 Jason Hall: to participate in and attend the opening of “Pasifika Styles”, Cambridge University of Iowa: towards a New Zealand MIT School of Visual Arts: towards its 2006 University writer -

The Robert Burns Fellowship 2018

THE ROBERT BURNS FELLOWSHIP 2018 The Fellowship was established in 1958 by a group of citizens, who wished to remain anonymous, to commemorate the bicentenary of the birth of Robert Burns and to perpetuate appreciation of the valuable services rendered to the early settlement of Otago by the Burns family. The general purpose of the Fellowship is to encourage and promote imaginative New Zealand literature and to associate writers thereof with the University. It is attached to the Department of English and Linguistics of the University. CONDITIONS OF AWARD 1. The Fellowship shall be open to writers of imaginative literature, including poetry, drama, fiction, autobiography, biography, essays or literary criticism, who are normally resident in New Zealand or who, for the time being, are residing overseas and who in the opinion of the Selection Committee have established by published work or otherwise that they are a serious writer likely to continue writing and to benefit from the Fellowship. 2. Applicants for the Fellowship need not possess a university degree or diploma or any other educational or professional qualification nor belong to any association or organisation of writers. As between candidates of comparable merit, preference shall be given to applicants under forty years of age at the time of selection. The Fellowship shall not normally be awarded to a person who is a full time teacher at any University. 3. Normally one Fellowship shall be awarded annually and normally for a term of one year, but may be awarded for a shorter period. The Fellowship may be extended for a further term of up to one year, provided that no Fellow shall hold the Fellowship for more than two years continuously. -

New Zealand and Pacific Literatures in Spanish Translation

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Open Journal Systems at the Victoria University of Wellington Library Reading (in) the Antipodes: New Zealand and Pacific Literatures in Spanish Translation PALOMA FRESNO-CALLEJA Abstract This article considers the Spanish translations of New Zealand and Pacific authors and explores the circumstances that have determined their arrival into the Spanish market as well as the different editorial and marketing choices employed to present these works to a Spanish readership. It considers the scarcity of canonical authors, the branding of Maori and other “ethnic” voices, the influence of film adaptations and literary prizes in the translation market, and the construction of the “New Zealand exotic” in works written by non-New Zealand authors which, in the absence of more translations from Spain’s literary Antipodes, have dominated the Spanish market in recent years. Introduction In October 2012, New Zealand was chosen as guest of honour at the Frankfurt Book Fair, the world’s largest and most prominent event of this type. The motto of the New Zealand delegation was: “He moemoea he ohorere / While you were sleeping,” an ingenious allusion to the geographical distance between Europe and its Antipodes, but also a reminder of the country’s literary potential, which Europeans were invited to wake up to. The choice of New Zealand as a guest of honour reflected the enormous interest of German readers for its literature and culture, summarized in Norman Franke’s remark that “Germans are crazy about all things Kiwi.”1 As Franke points out, more New Zealand books have been translated into German than into any other European language, and the impact of the fair resulted in an immediate increase of sales and a thirst for new titles.2 Spanish newspapers reported the event with curiosity but on a slightly skeptical note. -

Tina Makereti, the Novel Sleeps Standing About the Battle of Orakau and Native Son, the Second Volume of His Memoir

2017 AUTHOR Showcase AcademyAcademy ofof NewNew Zealand Zealand Literature Literature ANZLANZLTe WhareTe Whare Mātātuhi Mātātuhi o Aotearoa o Aotearoa Please visit the Academy of New Zealand Literature web site for in-depth features, interviews and conversations. www.anzliterature.com Academy of New Zealand Literature ANZL Te Whare Mātātuhi o Aotearoa Academy of New Zealand Literature ANZL Te Whare Mātātuhi o Aotearoa Kia ora festival directors, This is the first Author Showcase produced by the Academy of New Zealand Literature (ANZL). We are writers from Aotearoa New Zealand, mid-career and senior practitioners who write fiction, poetry and creative nonfiction. Our list of Fellows and Members includes New Zealand’s most acclaimed contemporary writers, including Maurice Gee, Keri Hulme, Lloyd Jones, Eleanor Catton, Witi Ihimaera, C.K. Stead and Albert Wendt. This showcase presents 15 writers who are available to appear at literary festivals around the world in 2017. In this e-book you’ll find pages for each writer with a bio, a short blurb about their latest books, information on their interests and availability, and links to online interviews and performances. Each writer’s page lists an email address so you can contact them directly, but please feel free to contact me directly if you have questions. These writers are well-known to New Zealand’s festival directors, including Anne O’Brien of the Auckland Writers Festival and Rachael King of Word Christchurch. Please note that New Zealand writers can apply for local funding for travel to festivals and other related events. We plan to publish an updated Author Showcase later this year. -

Hone Tuwhare's Aroha

ka mate ka ora: a new zealand journal of poetry and poetics Issue 6 September 2008 Hone Tuwhare’s Aroha Robert Sullivan This issue of Ka Mate Ka Ora is an appreciation of Hone Tuwhare’s poetry containing tributes by some of his friends, fans and fellow writers, as well as scholars outlining different aspects of his widely appreciated oeuvre. It was a privilege to be asked by Murray Edmond to guest-edit this celebration of Tuwhare’s work. I use the term work for Tuwhare’s oeuvre because he was brilliantly and humbly aware of his role as a worker, part of a greater class and cultural struggle. His humility is also deeply Māori, and firmly places him as a rangatira of people and poets. It goes without saying that this tribute acknowledges the passing of a very (which adverb to use here – greatly? hugely? extraordinarily?) significant New Zealand poet, and the first Māori author of a literary collection to be published in English. No Ordinary Sun was published by Blackwood and Janet Paul in September 1964. In September 2008, it is an understatement to say that New Zealand Māori literature in English has spread beyond its national boundaries, and that many writers, Māori and non-Māori, stand on Tuwhare’s shoulders. Having the words ‘ka mate’ and ‘ka ora’ together in this journal’s title, terms borrowed from New Zealand’s most famous poem, the ngeri by the esteemed leader and composer Te Rauparaha, feels appropriate for New Zealand’s most esteemed Māori poet in English. Tuwhare’s poetic – regenerative, sexually active, appetitive, pantheistic myth-referencing, choral-solo, light and shade, regional-personal, historical-immediate, high aesthetic registers mixed with popular vocals, class- conscious, ideologically aware, traditional Māori intersecting with contemporary Māori in English – captures the mauri or life-force and the dark duende of Te Rauparaha’s haka composition as it springs from the earth stamped in live performance. -

Landfall 238

LANDFALL 238 Edited by Emma Neale NEW TITLE INFORMATION SELLING POINTS OTAGO • Announcing winners of the Kathleen UNIVERSITY Grattan Award for Poetry, Landfall Essay Competition 2019, and the PRESS Caselberg Trust International Poetry Prize 2019 • Exciting contemporary art and writing PUBLICATION DETAILS FEATURED ARTISTS Landfall 238 Nigel Brown, Holly Craig, Emil McAvoy Edited by Emma Neale Otago University Press AWARDS & COMPETITIONS www.otago.ac.nz/press Results from the Kathleen Grattan Award for Poetry 2019, with judge’s report by Jenny Bornholdt; results and winning essays from the Landfall Essay Competition 2019, with judge’s Literature report by Emma Neale; results from the Caselberg Trust International Poetry Prize 2019, with Paperback, 215 x 165 mm judge’s report by Dinah Hawken. 208 pp, 16 in colour ISBN 978-1-98-853180-9, $30 WRITERS IN-STORE: NOV 2019 John Allison, Ruth Arnison, Emma Barnes, Pera Barrett, Nikki-Lee Birdsey, Anna Kate Blair, See below for ordering information Corrina Bland, Cindy Botha, Liz Breslin, Mark Broatch, Tobias Buck, Paolo Caccioppoli, Marisa Cappetta, Janet Charman, Whitney Cox, Mary Cresswell, Jeni Curtis, Jodie Dalgleish, Breton Dukes, David Eggleton, Johanna Emeney, Cerys Fletcher, David Geary, Miriama Gemmell, Susanna Gendall, Gail Ingram, Sam Keenan, Kerry Lane, Peter Le Baige, Helen Lehndorf, Kay McKenzie Cooke, Kirstie McKinnon, Zoë Meager, Lissa Moore, Margaret Moores, Janet Newman, Rachel O’Neill, Claire Orchard, Bob Orr, Jenny Powell, Nina Mingya Powles, Lindsay Rabbitt, Nicholas Reid, Jade Riordan, Gillian Roach, Paul Schimmel, Derek Schulz, Michael Steven, Chris Stewart, Robert Sullivan, Stacey Teague, Annie Villiers, Janet Wainscott, Louise Wallace, Albert Wendt, Iona Winter REVIEWS Landfall Review Online: books recently reviewed Shef Rogers on The Travels of Hildebrand Bowman, ed. -

3 October 2001

INTERNATIONAL INSTITUTE OF M ODERN LETTERS Te P¯utahi Tuhi Auaha o te Ao Newsletter – 3 October 2001 This is the 8th in a series of occasional newsletters from the Victoria University centre of the International Institute of Modern Letters. For more information about any of the items, please email [email protected]. 1. Double De Montalk ........................................................................................... 1 2. Allen Curnow ..................................................................................................... 1 3. Ian Wedde Reading ............................................................................................ 2 4. Oklahoma! .......................................................................................................... 2 5. The Stepmother Tree .......................................................................................... 2 6. Gladiator ............................................................................................................ 2 7. Fresh Talent in the City ...................................................................................... 2 8. Manawatu Festival of Women’s Words ............................................................ 3 9. London! .............................................................................................................. 3 10. Two Poetry Readings .......................................................................................... 3 11. Burns Fellow ..................................................................................................... -

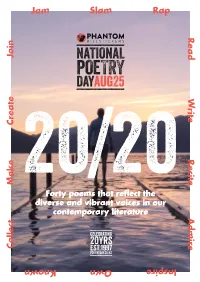

Jam Inspire Create Join Make Collect Slam Own Rap Known Read W Rite

Jam Slam Rap Read Join Write Create Recite Make 20/20 Forty poems that reflect the diverse and vibrant voices in our contemporary literature Admire Collect Inspire Known Own 20 ACCLAIMED KIWI POETS - 1 OF THEIR OWN POEMS + 1 WORK OF ANOTHER POET To mark the 20th anniversary of Phantom Billstickers National Poetry Day, we asked 20 acclaimed Kiwi poets to choose one of their own poems – a work that spoke to New Zealand now. They were also asked to select a poem by another poet they saw as essential reading in 2017. The result is the 20/20 Collection, a selection of forty poems that reflect the diverse and vibrant range of voices in New Zealand’s contemporary literature. Published in 2017 by The New Zealand Book Awards Trust www.nzbookawards.nz Copyright in the poems remains with the poets and publishers as detailed, and they may not be reproduced without their prior permission. Concept design: Unsworth Shepherd Typesetting: Sarah Elworthy Project co-ordinator: Harley Hern Cover image: Tyler Lastovich on Unsplash (Flooded Jetty) National Poetry Day has been running continuously since 1997 and is celebrated on the last Friday in August. It is administered by the New Zealand Book Awards Trust, and for the past two years has benefited from the wonderful support of street poster company Phantom Billstickers. PAULA GREEN PAGE 20 APIRANA TAYLOR PAGE 17 JENNY BORNHOLDT PAGE 16 Paula Green is a poet, reviewer, anthologist, VINCENT O’SULLIVAN PAGE 22 Apirana Taylor is from the Ngati Porou, Te Whanau a Apanui, and Ngati Ruanui tribes, and also Pakeha Jenny Bornholdt was born in Lower Hutt in 1960 children’s author, book-award judge and blogger.