For Peer Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IBNS Journal Volume 56 Issue 1

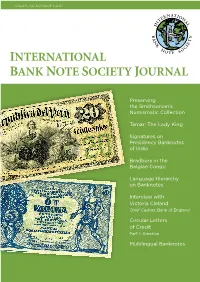

VOLUME 56, NUMBER 1, 2017 INTERNATIONAL BANK NOTE SOCIETY JOURNAL Preserving the Smithsonian’s Numismatic Collection Tamar: The Lady King Signatures on Presidency Banknotes of India Bradbury in the Belgian Congo Language Hierarchy on Banknotes Interview with Victoria Cleland Chief Cashier, Bank of England Circular Letters of Credit Part 1: America Multilingual Banknotes President’s Message Table of inter in North Dakota is such a great time of year to stay indoors and work Contents on banknotes. Outside we have months of freezing temperatures with Wmany subzero days and brutal windchills down to – 50°. Did you know that – 40° is the only identical temperature on both the Fahrenheit and Centigrade President’s Message.......................... 1 scales? Add several feet of snow piled even higher after plows open the roads and From the Editor ................................ 3 you’ll understand why the early January FUN Show in Florida is such a welcome way to begin the New Year and reaffirm the popularity of numismatics. IBNS Hall of Fame ........................... 3 This year’s FUN Show had nearly 1500 dealers. Although most are focused on U.S. Obituary ............................................ 5 paper money and coins, there were large crowds and ever more world paper money. It was fun (no pun intended) to see so many IBNS members, including several overseas Banknote News ................................ 7 guests, and to visit representatives from many auction companies. Besides the major Preserving the Smithsonian’s numismatic shows each year, there are a plethora of local shows almost everywhere Numismatic Collection’s with occasional good finds and great stories to be found. International Banknotes The increasing cost of collecting banknotes is among everyone’s top priority. -

Latin Derivatives Dictionary

Dedication: 3/15/05 I dedicate this collection to my friends Orville and Evelyn Brynelson and my parents George and Marion Greenwald. I especially thank James Steckel, Barbara Zbikowski, Gustavo Betancourt, and Joshua Ellis, colleagues and computer experts extraordinaire, for their invaluable assistance. Kathy Hart, MUHS librarian, was most helpful in suggesting sources. I further thank Gaylan DuBose, Ed Long, Hugh Himwich, Susan Schearer, Gardy Warren, and Kaye Warren for their encouragement and advice. My former students and now Classics professors Daniel Curley and Anthony Hollingsworth also deserve mention for their advice, assistance, and friendship. My student Michael Kocorowski encouraged and provoked me into beginning this dictionary. Certamen players Michael Fleisch, James Ruel, Jeff Tudor, and Ryan Thom were inspirations. Sue Smith provided advice. James Radtke, James Beaudoin, Richard Hallberg, Sylvester Kreilein, and James Wilkinson assisted with words from modern foreign languages. Without the advice of these and many others this dictionary could not have been compiled. Lastly I thank all my colleagues and students at Marquette University High School who have made my teaching career a joy. Basic sources: American College Dictionary (ACD) American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (AHD) Oxford Dictionary of English Etymology (ODEE) Oxford English Dictionary (OCD) Webster’s International Dictionary (eds. 2, 3) (W2, W3) Liddell and Scott (LS) Lewis and Short (LS) Oxford Latin Dictionary (OLD) Schaffer: Greek Derivative Dictionary, Latin Derivative Dictionary In addition many other sources were consulted; numerous etymology texts and readers were helpful. Zeno’s Word Frequency guide assisted in determining the relative importance of words. However, all judgments (and errors) are finally mine. -

Center for Southeast Asian Studies, Kyoto University 206 Book Reviews

http://englishkyoto-seas.org/ <Book Review> Ken MacLean Allison J. Truitt. Dreaming of Money in Ho Chi Minh City. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2013, xii+193p. Southeast Asian Studies, Vol. 4, No. 1, April 2015, pp. 206-209. How to Cite: MacLean, Ken. Review of Dreaming of Money in Ho Chi Minh City by Allison J. Truitt. Southeast Asian Studies, Vol. 4, No. 1, April 2015, pp. 206-209. Link to this article: http://englishkyoto-seas.org/2015/04/vol-4-no-1-book-reviews-ken-maclean/ View the table of contents for this issue: http://englishkyoto-seas.org/2015/04/vol-4-1-of-southeast-asian-studies Subscriptions: http://englishkyoto-seas.org/mailing-list/ For permissions, please send an e-mail to: [email protected] Center for Southeast Asian Studies, Kyoto University 206 Book Reviews People. New Delhi: Hindustan Pub. Corp. Wang, Zhusheng. 1997. The Jingpo: Kachin of the Yunnan Plateau. Tempe, AZ: Program for Southeast Asian Studies. Wyatt, David K. 1997. Southeast Asia ‘Inside Out,’ 1300–1800: A Perspective from the Interior. Modern Asian Studies 31(3): 689–709. Dreaming of Money in Ho Chi Minh City ALLISON J. TRUITT Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2013, xii+193p. The scholarly study of banknotes (notaphily) is not a new phenomenon. But it did not take sys- tematic modern form until the 1920s. (Ironically, it emerged under the Weimar Republic just as Germany was entering a three-year period of hyperinflation.) Since then, the number of numis- matic associations has grown considerably, as have specialized publications. -

March Rahul.Cdr

Editor : Siddharth N.S Co - Editor : Tejas Shah Sr. 3rd Year 34th Issue March 2018 Pages 12 22 62231833 e-mail - [email protected] Special Cover in Delhi National Museum 9th National Numismatic Rare Stamps on Women memory of Upendra Pai in need of a Numismatist Exhibition Bangaluru Achievers in Mangaluru Government Pays Two Times for Duplicate Sikh Coins Though Originals Available at Half Price hen the collection of original Sikh coins is available at half the price in the open market, the Punjab WGovernment has paid lakhs of rupees to a private firm just for minting duplicate coins. These coins will be placed at the upcoming Sikh Coins Museum at Gobindgarh Fort.For building interiors of the museum, the then SAD-BJP government had given a contract for Rs 5.5 crore to a Delhi-based firm. The contract also included Rs. 20 lakh for supplying duplicates of around 400 coins related to the Sikh history. The decision has raised eyebrows. According to numismatics, most of the original Sikh coins in copper are available anywhere between Rs. 150 and Rs. 200 and silver coins between Rs. 1,500 and Rs. 2,500. Cont on Page 4th ..... Collecting 'Fake Coins' – The Unknown Facet of Coin Collecting n the world of coin collecting, we are believed to stay away from the 'Fake' & 'Counterfeit' coins. Begetting any of these unknowingly Ileaves us in a state of dismay. Novelty coins, replica coins, copy coins… No matter what term we may use, those are fake coins! Coins that aren't 100 percent mint made has grown up into a huge collection for Mr. -

Stamp News Canadian

www.canadianstampnews.ca An essential resource for the CANADIAN advanced and beginning collector Like us on Facebook at www.facebook.com/canadianstampnews Follow us on Twitter @trajanpublisher STAMP NEWS Follow us on Instagram @trajan_csn Volume 44 • Number 24 March 17 - 30, 2020 $5.50 ‘Thanks for the Smokes’ Long-time reveals soldiers’ popular solace Unitrade By Jesse Robitaille Freedom to Smoke: Tobacco Con- Now considered a deadly sumption and Identity, and the habit killing nearly 40,000 Cana- main channel of proliferation editor has dians a year, smoking was was the mail. widely popular in decades past, The troops” “special including during the world need” was the cigarette, wrote deep hobby wars, when Canada’s annual Iain Gately in his 2001 book, La cigarette consumption exceeded Diva Nicotina: The Story of How two billion for the first time. Tobacco Seduced the World. The First World War “legiti- “Their slightest wish should roots mized the cigarette,” according be gratified, and in 18 out of 20 By Jesse Robitaille to Jarrett Rudy’s 2005 book, The Continued on page 38 This is the first story in a multi- part series exploring the recent history of the Unitrade Special- ized Catalogue of Canadian Stamps. n avid collector of modern Canadian stamps and pur- veyorA of all things philatelic, Robin Harris was seemingly Unitrade catalogue editor Robin Harris, of Manitoba, has made for the role of editor of been an active collector since the late 1960s. Unitrade’s long-running stamp catalogue. Published annually for more Harris, who added the previous 2005. A month later, it received a than two decades, the Unitrade editor was an employee of To- gold medal at Canada’s Seventh Specialized Catalogue of Canadian ronto’s Unitrade Associates National Philatelic Literature Ex- Stamps owes much of its evolu- who “wasn’t involved with hibition, which was held in con- tion to long-time editor Robin stamps.” junction with that year’s Harris, of Manitoba, who started There were dozens of updates Stampex in Toronto. -

MANAGEMENT in the FUNCTION of ENLARGEMENT of the ISSUING PROFIT Prof

Munich Personal RePEc Archive Management in the Function of Enlargement of the Issuing Profit Matić, Branko J. J. Strossmayer University of Osijek, Faculty of Economics 2005 Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/10857/ MPRA Paper No. 10857, posted 01 Oct 2008 08:47 UTC MANAGEMENT IN THE FUNCTION OF ENLARGEMENT OF ... 115 MANAGEMENT IN THE FUNCTION OF ENLARGEMENT OF THE ISSUING PROFIT Prof. Dr. Branko Mati} Faculty of Economics in Osijek Summary The author starts from the thesis that it is especially necessary to manage the production of cash money, taking into consideration and applying the conceptions of modern management. Cash money (metallic and paper) is a specific “product” that is produced according to the needs of monetary traffic, as well as meeting the standards related to modern notaphily, i.e. numismatics. For several reasons, the author elaborates his thesis on the example of the issuing of Croatian contemporary metallic money. The most important of these reasons are that Croatia has its own mint, that issuing metallic money makes it possible to attain significant non-fiscal effects through its management, and that the issuing of national money has wider cultural, social, legal and other dimensions. In the elaboration of his thesis, the author takes into account the influence of the globalization and integration proces- ses in which Croatia is a participant. Key words: management, innovation, issuing profit, money, exchange rate, Euroland 1. Introduction The notion of contemporary Croatian monetary system is connected with the establishment of the sovereignty of the Republic of Croatia. After declaring its inde- pendence (on 30th May 1990) on 23rd December 1991 Croatia introduced its tran- sitional, temporary monetary unit - the Croatian Dinar. -

Page 13 « IBSS AGM NEWS Tennessee Copper « BOOK REVIEWS « on the ROAD? Dutch Plantations in the East Indies – Page 17

SCRIPOPHILYTHE JOURNAL OF THE INTERNATIONAL BOND & SHARE SOCIETY ENCOURAGING COLLECTING SINCE 1978 No.94 - APRIL 2014 Just Deserts Rare Comstock – page 10 Belgian Investments The high price of in Romania – page 20 – page 13 « IBSS AGM NEWS Tennessee Copper « BOOK REVIEWS « ON THE ROAD? Dutch plantations in the East Indies – page 17 Scripophily Top 100 Worldwide Auction News The newest centurion at $35,700 – page 23 – page 6 Interesting Reaching specimens at out to a National Show billion users THE JOURNAL OF THE INTERNATIONAL BOND & SHARE SOCIETY SCRIPOPHILY ENCOURAGING COLLECTING SINCE 1978 INTERNATIONAL BOND & SHARE SOCIETY APRIL 2014 • ISSUE 94 CHAIRMAN - Andreas Reineke Alemannenweg 10, D-63128 Dietzenbach, Germany. Tel: (+49) 6074 33747. Email: [email protected] SOCIETY MATTERS 2 DEPUTY CHAIRMAN - Mario Boone NEWS AND REVIEWS 5 Kouter 126, B-9800 Deinze, Belgium. Tel: (+32) 9 386 90 91 Fax: (+32) 9 386 97 66. Email: [email protected] • World Top 100 • Wells Fargo Mining Co SECRETARY & MEMBERSHIP SECRETARY - Philip Atkinson 167 Barnett Wood Lane, Ashtead, Surrey, KT21 2LP, UK. • IBSS AGM • Book Reviews Tel: (+44) 1372 276787. Email: [email protected] • National Show .... and more besides TREASURER - Martyn Probyn Flat 2, 19 Nevern Square, London, SW5 9PD, UK COX’S CORNER 11 T/F: (+44) 20 7373 3556. Email: [email protected] AUCTIONEER - Bruce Castlo FEATURES 1 Little Pipers Close, Goffs Oak, Herts EN7 5LH, UK. Tel: (+44) 1707 875659. Email: [email protected] On the Road? Visit a Fellow Scripophilist! 12 MARKETING - Martin Zanke by Max Hensley Glasgower Str. 27, 13349 Berlin, Germany. 13 Tel: (+49) 30 6170 9995. -

Dreaming of Money in Ho Chi Minh City Seattle

Kyoto University 206 Book Reviews People. New Delhi: Hindustan Pub. Corp. Wang, Zhusheng. 1997. The Jingpo: Kachin of the Yunnan Plateau. Tempe, AZ: Program for Southeast Asian Studies. Wyatt, David K. 1997. Southeast Asia ‘Inside Out,’ 1300–1800: A Perspective from the Interior. Modern Asian Studies 31(3): 689–709. Dreaming of Money in Ho Chi Minh City ALLISON J. TRUITT Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2013, xii+193p. The scholarly study of banknotes (notaphily) is not a new phenomenon. But it did not take sys- tematic modern form until the 1920s. (Ironically, it emerged under the Weimar Republic just as Germany was entering a three-year period of hyperinflation.) Since then, the number of numis- matic associations has grown considerably, as have specialized publications. Banknote News is one relevant example. Banknote News issues breaking stories about international paper and polymer money. Collectors are the primary audience, and the website contains hundreds of links to vendors for people who wish to purchase the bank notes they covet. One of the links directs collectors to the 2014 edition of The Banknote Book. It includes 205 stand-alone chapters, each of which can be purchased separately as a country-specific catalog. (The Vietnam chapter provides detailed infor- mation on notes the State Bank of Vietnam issued, but only from 1964 to present, color copies of them, as well as their current market valuations.) The four-volume set currently runs 2,554 pages and details more than 21,000 types and varieties of currency, some dating back centuries. The global community of currency collectors and the desires that shape their relationships to different forms of money provides a useful entry point into Allison Truitt’s fascinating book, Dream- ing of Money in Ho Chi Minh City. -

A Study on Currency and Coinage Circulation in India

International Journal of Trade, Economics and Finance, Vol. 4, No. 1, February 2013 A Study on Currency and Coinage Circulation in India Srinivasan Chinnammai coins would be up to 20 years. Abstract—In India, currency forms a significant part of The same author (2009) [4] has spoken of the new 5- money supply. Money supply is generally viewed in two senses. rupee coin launched in Chennai city, made of nickel and Money supply in the conventional sense includes notes and brass. The introduction of this new coin was in light of coins in circulation (nominally claims against the central bank complaints about difficulties in differentiating between the and / or the government of the country) plus those deposits coins in the denomination of five rupees and 50 paise. with banks which are repayable on demand. This is also The Hindu, (2011) [5] has come out with the article of referred to as the narrow definition of money supply and is RBI’s meeting with press persons and the former’s widely known as M1. When time deposits with banks are added to M1, the definition of money supply becomes broader announcement of legally invalidating the circulation of coins and is in India known as M3. However, this research study in the denomination of 25 paise and below from June 30, focuses only on the aspect of banknotes and coins, which is a 2011. There was no direct answer from the RBI personnel part of M1, but plays a vital role in currency management. when asked whether 50 paise coins will also be dealt the same way in due course of time. -

Lietuvos Muziejų Rinkiniai 2009 / 08

LIETUVOS MUZIEJŲ ASOCIACIJA RINKINIŲ MOKSLINIO TYRIMO SEKCIJA LIETUVOS MUZIEJŲ RINKINIAI XII konferencija LITUANISTIKA MUZIEJUOSE, skirta Lietuvos vardO pAMINėJIMO TūkstantmečIUI * * * COLLECTIONS OF LITHUANIAN MUSEUMS The 12th Scientific Conference LITUANISTIC MATERIALS AT MUSEUMS, dEdicated to THE MILLENNIUM OF THE FIRST REFERENCE to THE name OF Lithuania LIETUVOS NACIONALINIS MUZIEJUS, 2009 m. balandžio 28 d. NATIONAL MUSEUM OF LITHUANIA, April 28, 2009 ISSN 1822-0657 Konferencijos organizacinis komitetas, leidinio redakcinė kolegija Vingaudas Baltrušaitis, Lietuvos liaudies buities muziejus Žygintas Būčys, Lietuvos nacionalinis muziejus Birutė Salatkienė, Šiaulių ,,Aušros“ muziejus Janina Samulionytė, Lietuvos liaudies buities muziejus Virginija Šiukščienė, Šiaulių ,,Aušros“ muziejus Sudarytoja Virginija Šiukščienė Konferencijos ir leidinio rėmėjai Lietuvos Respublikos kultūros ministerija Lietuvos muziejų asociacija Lietuvos nacionalinis muziejus Šiaulių ,,Aušros“ muziejus Viršeliuose: pirmajame – Lietuvos nacionalinis muziejus, ketvirtajame – apeiginė briedės galvos formos lazda. Ragas, III tūkst. pr. Kr. Šventoji 3. LNM Fot. Kęstutis Stoškus © Lietuvos muziejų asociacija, 2009 © Lietuvos nacionalinis muziejus, 2009 © Šiaulių ,,Aušros“ muziejus, 2009 TURINyS Mokslinės konferencijos ,,Lituanistika muziejuose“, skirtos Lietuvos vardo paminėjimo tūkstantmečiui, straipsniai . 5 Eugenija Rudnickaitė, Justinas Kišūnas, Gediminas Motuza. Vilniaus universiteto Geologijos ir mineralogijos katedra / Vilnius University, Department of Geology -

Commemorative Metal Money and Monetary Economy

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Munich RePEc Personal Archive MPRA Munich Personal RePEc Archive Commemorative Metal Money and Monetary Economy Branko Mati´c J. J. Strossmayer University of Osijek, Faculty of Economics 2001 Online at http://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/7424/ MPRA Paper No. 7424, posted 4. March 2008 08:58 UTC Commemorative Metal Money and Monetary Economy D. Sc. Branko Mati ć, Assistant Professor, Faculty of Economics in Osijek, Gajev trg 7, Osijek, Croatia Summary: The subject of study of monetary economy is money, its forms and functions and its economic and reproductive role. Since modern money is a very heterogeneous category, an adequate money issue policy makes it possible with particular forms of money to achieve some additional effects. This primarily refers to commemorative coins, the issue of which may bring significant economic effects based on numismatic designs. In this way, this kind of money may get another role in monetary economy. Such approach does not lessen the basic functions of commemorative money, such as the function of preserving value, the function of a means of transaction, the function of a means of payment or its commercial function. Planned activities in relation to the introduction of cash money, including commemorative coinage, iil most European Union countries in the year 2002, among other things, will also have important influence on Croatian money issue policy regarding commemorative coinage. The reasons for this are the development of money issue activities in the sphere of coinage, especially in the segment of commemorative coins in the European Union countries, and the readiness of Croatia to participate in that association. -

Of Words 221

www.ZTCprep.com ffirs.qxd 7/21/05 12:07 PM Page i Another Word A Day www.ZTCprep.com ffirs.qxd 7/21/05 12:07 PM Page ii Also by Anu Garg A Word A Day: A Romp through Some of the Most Unusual and Intriguing Words in English www.ZTCprep.com ffirs.qxd 7/21/05 12:07 PM Page iii Another Word A Day An All-New Romp through Some of the Most Unusual and Intriguing Words in English Anu Garg John Wiley & Sons, Inc. www.ZTCprep.com ffirs.qxd 7/21/05 12:07 PM Page iv Copyright © 2005 by Anu Garg. All rights reserved Published by John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey Published simultaneously in Canada Composition by Navta Associates, Inc. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750-8400, fax (978) 646-8600, or on the web at www.copyright.com. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, (201) 748-6011, fax (201) 748-6008, or online at http://www.wiley.com/go/permissions. Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty:While the publisher and the author have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this book and specifically disclaim any implied war- ranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose.