Complications

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CARDIOLOGY Section Editors: Dr

2 CARDIOLOGY Section Editors: Dr. Mustafa Toma and Dr. Jason Andrade Aortic Dissection DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS PATHOPHYSIOLOGY (CONT’D) CARDIAC DEBAKEY—I ¼ ascending and at least aortic arch, MYOCARDIAL—myocardial infarction, angina II ¼ ascending only, III ¼ originates in descending VALVULAR—aortic stenosis, aortic regurgitation and extends proximally or distally PERICARDIAL—pericarditis RISK FACTORS VASCULAR—aortic dissection COMMON—hypertension, age, male RESPIRATORY VASCULITIS—Takayasu arteritis, giant cell arteritis, PARENCHYMAL—pneumonia, cancer rheumatoid arthritis, syphilitic aortitis PLEURAL—pneumothorax, pneumomediasti- COLLAGEN DISORDERS—Marfan syndrome, Ehlers– num, pleural effusion, pleuritis Danlos syndrome, cystic medial necrosis VASCULAR—pulmonary embolism, pulmonary VALVULAR—bicuspid aortic valve, aortic coarcta- hypertension tion, Turner syndrome, aortic valve replacement GI—esophagitis, esophageal cancer, GERD, peptic OTHERS—cocaine, trauma ulcer disease, Boerhaave’s, cholecystitis, pancreatitis CLINICAL FEATURES OTHERS—musculoskeletal, shingles, anxiety RATIONAL CLINICAL EXAMINATION SERIES: DOES THIS PATIENT HAVE AN ACUTE THORACIC PATHOPHYSIOLOGY AORTIC DISSECTION? ANATOMY—layers of aorta include intima, media, LR+ LRÀ and adventitia. Majority of tears found in ascending History aorta right lateral wall where the greatest shear force Hypertension 1.6 0.5 upon the artery wall is produced Sudden chest pain 1.6 0.3 AORTIC TEAR AND EXTENSION—aortic tear may Tearing or ripping pain 1.2–10.8 0.4–0.99 produce -

Isolated Left Ventricular Pulsus Alternans

Case Report Olgu Sunumu 79 Isolated left ventricular pulsus alternans; an echocardiographic finding in a patient with discrete subaortic stenosis and infective endocarditis Diskret subaortik darl›k ve infektif endokardit bulunan bir hastada bir ekokardiyografi bulgusu: ‹zole sol ventriküler pulsus alternans Mehmet Uzun, Cem Köz, Oben Baysan, Kürflad Erinç, Mehmet Yokuflo¤lu, Hayrettin Karaeren Department of Cardiology, Gülhane Military Medical Academy, Etlik, Ankara, Turkey Introduction revealed 4/6 systolic murmur best heard over upper right sternal border, radiating to both sides of the neck, and fever of 38.8oC. Af- Pulsus alternans, alternating weak and strong beat in the ter physical examination, the patient was referred to the echo- presence of stable heart rate and QRS complex, is generally ac- cardiography laboratory. The echocardiographic examination cepted as a finding of physical examination. It is most often as- revealed a subaortic discrete membrane and a mobile mass over sociated with moderate or severe heart failure (1). After the int- the noncoronary cusp of the aortic valve (Fig.1). The internal di- roduction of echocardiography to clinical practice, there has be- ameter of left ventricle was 65 mm and constant (Fig. 2). The en some debate about whether all alternating contractions are ejection fraction measured by modified Simpson method was reflected in peripheral pulses (2). In this report, we present a ca- between 35% and 37% on consecutive 5 beats. Color flow Dopp- se of echocardiographically detected left ventricular alternans, ler examination showed moderate mitral and moderate aortic re- which has not been reflected in peripheral pulse. gurgitation. Doppler interrogation of the left ventricular outflow tract revealed two alternating peak gradients: 118 mmHg and Case report 88 mmHg (Fig. -

Pulsus Alternans Figure 1. Teleme

Medical Image of the Week: Pulsus Alternans Figure 1. Telemetry display including arterial pressure waveform, which demonstrates alternating beats of large (large arrows) and small (small arrows) pulse pressure. Concurrent pulse oximetry could not be performed at the time of the image due to poor peripheral perfusion. A 52 year old man with a known past medical history of morbid obesity (BMI, 54.6 kg/m2), heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, hypertension, untreated obstructive sleep apnea, and obesity hypoventilation syndrome presented with increasing dyspnea over several months accompanied by orthopnea and weight gain that the patient had treated at home with a borrowed oxygen concentrator. On arrival to the Emergency Department, the patient was in moderate respiratory distress and hypoxic to SpO2 70% on room air. Physical examination was pertinent for pitting edema to the level of the chest. Assessment of jugular venous pressure and heart and lung auscultation were limited by body habitus, but chest radiography suggested pulmonary edema. The patient refused aggressive medical care beyond supplemental oxygen and diuretic therapy. Initial transthoracic echocardiography was limited due to poor acoustic windows but suggested a newly depressed left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) of <25%. The cause, though uncertain, may have been reported recent amphetamine use. The patient deteriorated, developing shock and respiratory failure; after agreeing to maximal measures, ventilatory and inotropic/vasopressor support was initiated. Shortly after placement of the arterial catheter, the ICU team was called to the bedside for a change in the arterial pressure waveform (Figure 1), which then demonstrated alternating strong (arrow) and weak beats (arrow head) independent of the respiratory cycle. -

On a Case of Pulsus Bigeminus Or Cardiac Couple-Beat, Complicated by a Quadruple Aortic Murmur *

ON A CASE OF PULSUS BIGEMINUS OR CARDIAC COUPLE-BEAT, COMPLICATED BY A QUADRUPLE AORTIC MURMUR * By J. WALLACE ANDERSON, M.D., Physician to the Royal Infirmary, Glasgow. Mr. President and Gentlemen,?I am about to narrate shortly to you this evening a case which may be described as having just escaped being one simply of aortic obstruction and regurgitation, occurring as a consequence and a complication of repeated attacks of sub-acute rheumatism. This, I might say, is the proposition of my subject; and I ask your attention to it, as it is the key to what would otherwise be an obscure ?and difficult case. I say it narrowly escaped being one simply of ordinary obstruction and regurgitation. But there was in addition that peculiar rhythm of the heart?itself worthy of remark?known as "couple-rhythm," or the pulsus bigeminus; ?and these two associated conditions brought out a very rare, in my experience a unique, cardiac phenomenon, namely, <a distinct quadruple aortic murmur. T. P., aged 24, tinsmith, was admitted to Ward VII of the Royal Infirmary, on 28th October, 1890, complaining of pains in the chest and back of left shoulder, and also of indigestion. The family history has no special bearing on the case, except that his father had occasionally rheumatic pains in his knees. Personal History.?With the exception of his having had measles in early childhood, he enjoyed uninterrupted health till he had rheumatic fever when 12 years of age. This would be in 1878. The attack appears to have been followed by a transient chorea. -

The Cardiovascular History and Physical Examination Roger Hall and Iain Simpson

CHAPTER 1 The Cardiovascular History and Physical Examination Roger Hall and Iain Simpson Contents Summary 1 Summary Introduction 2 History 2 A cardiovascular history and examination are fundamental to accurate Introduction diagnosis and the subsequent delivery of appropriate care for an individual The basic cardiovascular history Chest pain patient. Time spent on a thorough history and examination is rarely wasted Shortness of breath (dyspnoea) and goes beyond the gathering of basic clinical information as it is also an Paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnoea Cheyne–Stokes respiration opportunity to put the patient at ease and build confi dence in the physi- Sleep apnoea cian’s ability to provide a holistic and confi dential approach to their care. Cough Palpitation(s) (cardiac arrhythmias) This chapter covers the basics of history taking and physical examination Presyncope and syncope of the cardiology patient but then takes it to a higher level by trying to ana- Oedema and ascites Fatigue lyse the strengths and weaknesses of individual signs in clinical examina- Less common cardiological symptoms tion and to put them into the context of common clinical scenarios. In an Using the cardiovascular history to identify danger areas ideal world there would always be time for a full clinical history and exami- Some cardiovascular histories which nation, but clinical urgency may dictate that this is impossible or indeed, require urgent attention The patient with valvular heart disease when time critical treatment needs to be delivered, it may be inappropri- Examination 12 ate. This chapter provides an insight into delivering a tailored approach in Introduction General examination certain, common clinical situations. -

Easy Way to History Taking and Physical Examination

First Edition Easy Way To History Taking And Physical Examination Introduction The Name Of Allah The Most Gracious The Merciful We Are Swaed Team , Putting This Book In Your Hand Dear Student . We Hope This Book Will Help You In Your Medical Courses As A Fast And Simple Source Of Informations That You Will Need To Improve Your Clinical Skill . About The Team : The Team Aims To Lend A Helping Hand For Medical Students In Different Years Through The Work Of A Group Of Abstracts That Would Contribute To Facilitating Studying And Recalling The Informations . Names Of Participants - Raed Hamad Hassan Rayani . - Suzan Ali Mohammed Alhazmi . - Ebtehal Zaid Mahdi Alqahtani . - Tahani Ahmed Moasa Moafa . - Rafan Abdulrahman Mohammad Madkor . - Shatha Ibrahim Qassem Alqassemi . - Mona Ali Mansour Gahtani . - Rafaa Hassan Ali Fathi . - Muath Hassan Ibrahim Najmi . - Wedad Mohammad Mohammad Alhazmi . - Arwa Ahmed Ali Abutaleb . - Nadiah Taher Ali Somily . - Mathab Ali Abdulwahab Jarad . - Nehad Khalaf Mohammad Khawaji . - Mymona Abdullah Sulaiman Alfaifi . - Nourah Hamad Soliman Alkeaid . - Feras Essa Mohammed Al-Omar . - Alrumaisaa Ahmad Abdu Daafi . - Abdulrahman Ali Ahmed Khawaji . - Nouf Mohammed Ahmed Mari . - Ali Mansor Taher Sumayli . - Ali Mohammed Abdu Abutaleb . - Duaa Thyabi Yahya Hakami . - Azhar Ahmad Abdu Halawi . - Aisha Yahya Mohammad ALkhaldy . - Samira Mohammed Ali Nasib . - Nada Mohammad Hasser Hakami . - Saud Abdulaziz Musa Alqhtany . - Ahmed Hadi Ahmed Alkhormi . - Azhar Eisa Lahige Dallak . - Amnah Ali Azzam Shubayli . - Reem Mohammed Yahya Kariri . - Taysir Hassan Jadduh Hakami . Contact Informations # e-Mail : [email protected] # Twitter : @RaedRayani " https://twitter.com/RaedRayani " @Swaed_Team " https://twitter.com/Swaed_Team " # Facebook : Raed Rayani " https://www.facebook.com/raed.rayani " We Are Pleased To Receive Your Comments And Suggestions On This Email " [email protected] " Book Contents Internal Medicine ……………………….. -

The Venous and Liver Pulses, and the Arhythmic Contraction of the Cardiac Cavities

THE VENOUS AND LIVER PULSES, AND THE ARHYTHMIC CONTRACTION OF THE CARDIAC CAVITIES. By JAMES JfACKENZIE, M.D., Holboritmj DIcdical OBcer, Vieloi-iii Hospital, Buriklcy. (Continued from page 154.) THE following case presents iuaiiy features of interest, indicative of the manner in which the various factors influence the venous pulse :- CASE 17.-Female, st. 30; has had rlieuniatic fever at the ages of 11, 16, and 21, and has had heart disease since she TVRS 16 years of age. She had n child 5 years ago, and did not suffer in consequence. She becanie pregnant in July of 1891. She was very sick at first, and be- came very short of breath ; swelling of the legs came on in November. These syniptoms became worse “’ltil Ja’luary 1892, when Fro. 57.-Tracings of carotid and jugular pulse, taketi her in- together. The chief point in this tracing is the de- ‘lncecl premature labour* pression 2, in striking contrast to the wave that She very for a long appears later at this period ; see Fig. 58 (Case 17). time after, and when I first saw her on the 25th May 1892 she had fairly recovered, and was able to get up tind go about. There was only a slight venous pulse, evidently of the auricular form (Fig. 57). She came under my care again on 23rd July 1892, and her condition was then as follows :- She mas very short of breath, and lay propped up in bed. There was considerable swelling of the legs, also puffiness of the face. The pulse was small and quick, 80 per minute. -

Pulsus Alternans After Aortic Valve Replacement

Letters to Editor RT-3D-TEE has ability to demonstrate tumor REFERENCES characteristics in its en-face view, which may be more 1. Asch FM, Bieganski SP, Panza JA, Weissman NJ. Real-time 3-dimensional convincingly appreciated by the operating surgeon echocardiography evaluation of intracardiac masses. Echocardiography than the 2D imaging. It facilitates understanding of 2006;23:218-24. attachments of the myxoma to different parts of the 2. Mehmood F, Nanda NC, Vengala S, Winokur TS, Dod HS, Frans E, et al. Live three-dimensional transthoracic echocardiographic assessment of LA; structural damage to the mitral valve; and degree left atrial tumors. Echocardiography 2005;22:137-43. of free space available for blood flow inside the LA and 3. Culp WC Jr, Ball TR, Armstrong CS, Reiter CG, Johnston WE. Three- across the mitral valve. dimensional transesophageal echocardiographic imaging and volumetry of giant left atrial myxomas. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 2009;23:66-8. Isolated echolucent areas observed on live RT-3D-TEE are consistent with hemorrhage/necrosis in the tumor mass. These findings are typical of a myxoma and the Pulsus alternans after areas of echolucencies correspond to tumor hemorrhages and/or necrosis found on pathological examination of aortic valve replacement: the resected myxomas.[2] This echocardiographic feature Intraoperative recognition of a LA myxoma may be utilized to differentiate it from a hemangioma, which comprises much more extensive and role of TEE and closely packed echolucencies practically involving the whole extent of the tumor mass with relatively DOI:10.4103/0971-9784.62932 sparse solid tissue. Virtual cropping at different sequential levels in the three-dimensional data set Sir, enabled us to demonstrate echolucencies, which was Pulsus alternans (P ) is beat-to-beat variability in not possible on 2D examination. -

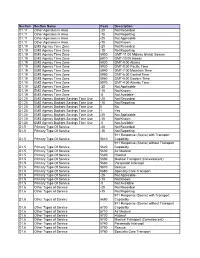

20 Not Recorded D1.11 Other Agencies in Area -15 Not Reporti

Section Section Name Code Description D1.11 Other Agencies in Area -20 Not Recorded D1.11 Other Agencies in Area -15 Not Reporting D1.11 Other Agencies in Area -25 Not Applicable D1.11 Other Agencies in Area -10 Not Known D1.19 EMS Agency Time Zone -20 Not Recorded D1.19 EMS Agency Time Zone -15 Not Reporting D1.19 EMS Agency Time Zone 5900 GMT-11:00 Midway Island, Somoa D1.19 EMS Agency Time Zone 5910 GMT-10:00 Hawaii D1.19 EMS Agency Time Zone 5920 GMT-9:00 Alaska D1.19 EMS Agency Time Zone 5930 GMT-8:00 Pacific Time D1.19 EMS Agency Time Zone 5940 GMT-7:00 Mountain Time D1.19 EMS Agency Time Zone 5950 GMT-6:00 Central Time D1.19 EMS Agency Time Zone 5960 GMT-5:00 Eastern Time D1.19 EMS Agency Time Zone 5970 GMT-4:00 Atlantic Time D1.19 EMS Agency Time Zone -25 Not Applicable D1.19 EMS Agency Time Zone -10 Not Known D1.19 EMS Agency Time Zone -5 Not Available D1.20 EMS Agency Daylight Savings Time Use -20 Not Recorded D1.20 EMS Agency Daylight Savings Time Use -15 Not Reporting D1.20 EMS Agency Daylight Savings Time Use 0 No D1.20 EMS Agency Daylight Savings Time Use 1 Yes D1.20 EMS Agency Daylight Savings Time Use -25 Not Applicable D1.20 EMS Agency Daylight Savings Time Use -10 Not Known D1.20 EMS Agency Daylight Savings Time Use -5 Not Available D1.5 Primary Type Of Service -20 Not Recorded D1.5 Primary Type Of Service -15 Not Reporting 911 Response (Scene) with Transport D1.5 Primary Type Of Service 5610 Capability 911 Response (Scene) without Transport D1.5 Primary Type Of Service 5620 Capability D1.5 Primary Type Of Service 5630 -

Blood Pressure, Heart Tones, and Diagnoses

14 Blood Pressure, Heart Tones, and Diagnoses GEORGE BOJANOVf MD CONTENTS BLOOD PRESSURE HEART TONES SUMMARY SOURCES 1. BLOOD PRESSURE In 1916, French physician Rene Laennec invented the first Fundamental to providing comprehensive care to patients is stethoscope, which was constructed from stacked paper rolled the ability to obtain an accurate medical history and carefully into a solid cylinder. Prior to his invention, physicians around perform and interpret a physical examination. The optimal the world would place one of their ears directly on the patient's selection of further tests, treatments, and use of subspecialists chest to hear heart or lung sounds. After Dr. Laennec's initial depends on well-developed skills for taking patient history and success, several new models were produced, primarily of wood. a physical diagnosis. An important part of a normal physical His stethoscope was called a"monaural stethoscope." The "bin- examination is obtaining a blood pressure reading and auscul- aural stethoscope" was invented in 1829 by a physician named tation of the heart tones, which both represent critical corner- Camman in Dublin and later gained wide acceptance; in the stones in evaluating a patient's hemodynamic status and 1960s, the Camman stethoscope was considered the standard diagnosing and understanding physiological and anatomical for superior auscultation. pathology. It is essential that health care professionals and bioengi- Naive ideas about circulation and blood pressure date as far neers understand how these important diagnostic parameters back as ancient Greece. It took until the 18th century for the are obtained, their sensitivities, and how best to interpret them. first official report to describe an attempt to measure blood pressure, when Stephen Hales published a monograph on 1.1. -

The Physiologic Mechanisms of Cardiac and Vascular Physical Signs

184 J AM cou. CARDIOl 1983:1:184-98 The Physiologic Mechanisms of Cardiac and Vascular Physical Signs JOSEPH K. PERLOFF, MD, FACC Los Angeles. California Examination of the heart and circulation includes five relate cardiac and vascular physicalsigns to their mech• items: 1) the patient's physical appearance, 2) the ar• anisms, focusing on each of the five sources. It draws terial pulse, 3) the jugular venous pulse and peripheral liberally on early accounts, emphasizing that modern veins, 4) the movements of the heart-observation, pal• investigative techniques often serve chiefly to verify hy• pation and percussion of the precordium, and 5) aus• potheses posed in the past. cultation. This report deals with specific examples that I shall begin by acknowledging three debts. The first is to chain of events, has provided answers to many of the re• the late Paul Wood and his staff at the Institute of Car• maining questions (2,3). diology , London, where my under standing of the physio• Let us now tum to specific examples that relate cardiac logic meaning of cardiac and vascular physical signs began. and vascular physical signs to their mechanisms, focusin g The second debt is to the Fulbright Foundation and the on each of the five sources mentioned. In so doing, certain Institute for International Education for making my year in illustrative examples will be selected. No attempt will be England possible. The third debt is to the National Institutes made to be comprehensive. of Health for providing my first research grant , which sup• ported the continuation of these studies in the United States. -

The Cardiovascular System

THE CARDIOVASCULAR SYSTEM. Create PDF files without this message by purchasing novaPDF printer (http://www.novapdf.com) HISTORY Create PDF files without this message by purchasing novaPDF printer (http://www.novapdf.com) PRESENTING COMPLAINTS. • Chest pain. • Fatigue. • Dyspnea. • Palpitations. • Presyncope/syncope. • Lower limb swelling. • Abdominal distension. Create PDF files without this message by purchasing novaPDF printer (http://www.novapdf.com) History of chronic diseases. • Thyroid disease, connective tissue diseases, neoplastic diseases, TB. • RHD and HTN – valvular disease. • DM, dyslipidaemias and smoking – ACS. • Alcohol, drugs – arrhythmias, cardiomyopathies. Create PDF files without this message by purchasing novaPDF printer (http://www.novapdf.com) Family history. • ACS. • HTN. • Cardiomyopathies. Create PDF files without this message by purchasing novaPDF printer (http://www.novapdf.com) Chest pain. • ACS • Pericarditis. • Aortic dissection. Create PDF files without this message by purchasing novaPDF printer (http://www.novapdf.com) Myocardial ischaemia(angina) Typical patient • Middle-aged or elderly man or woman often with a family history of coronary heart disease and one or more of the major reversible risk factors (smoking, hypertension, hypercholesterolaemia) Major symptoms • Exertional chest pain and shortness of breath. Pain often described as 'heaviness' or 'tightness', and may radiate into arms, neck or jaw Major signs • None, although hypertension and signs of hyperlipidaemia (xanthelasmata, xanthomas) may