The Wildlife of the Trap Grounds

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Common Insects of Freshwater Pond and Their Control ~

COMMON INSECTS OF FRESHWATER POND AND THEIR CONTROL ~ Bulletin No. 54 Krishna Mitra and Kuldip Kumar 11 ~3r.J!I leAR CENTRAL INLAND CAPTURE FISHERIES RESEARCH INSTITUTE (Indfan Council of Agricultural Research) Barrackpore - 743101 West Bengal India. COMMON INSECTS OF FRESHWATER PONDS AND THEIR CONTROL Bulletin No. 54 March 1988 Krishna Mitra and Kuldip Kumar IfII'JrF ICAR CENTRAL INLAND CAPTURE FISHERIES RESEARCH INSTITUTE (Indian Council of Aqricultural Research) Barrackpore - 743101 West Bengal India. CONTENTS Introduction 1 Classification of insects 2 Order EPHEMEROPTERA 2 Family : Baetidae 2 Order ODONATA 3 Family: Libellulidae 4 Aeshnidae 5 Coenagrtonldae 5 Order HEMIPTERA 6 Family: Gerridae 7 Notonectidae 7 Pleidae 8 Nepidae 9 Belostomatidae 10 Cortxtdae 11 Order COLEOPTERA 12 Family : Dytiscidae 13 Hydrophilidae - 14 Gyrinidae 16 Curculionidae 16 Contents (contd.) Order TRICHOPTERA 17 Family: Leptocertdae 17 Order LEPIDOPTERA 18 Family: Pyralidae 18 Order DIPTERA 19 Family: Culicidae 19 Tendipedidae 20 Heleidae 20 Stratlomytdae 21 Tabanidae 21 Muscidae 22 Control 23 Acknowledgements 24 References 25 Enlarged text figures 2.5. ~--~------------------------~---I Foreword The insects which constitute an important component oJ the littoral Jauna oJ aquatic ecosystems play a vital role in the trophic structure and Junctions oJ culturable water bodies. Their primary role as converters oJ plant materials into animal protein and consumers oJ organic wastes oJ the fisti habitat is of great signifzcance Jor the healthy growth of fish populations. Though the insects serve as a source oJ natural food. for fishes, they ofteti impair the fist: productivity in the pond ecosystem by predating upon their young ones. By sharing a common trophic niche with the fist: Juveniles they also compete with them Jor food. -

Key Destinations Ticket Options

travelling to Oxford St John Street towards: located along Parks Rd on key destinations Richmond Rd 4 5 the eastern side. Near the Rail Station W Kidlington Oxford University Science o Oxford Bus Company If you need to get to Oxford rail station then St Giles Pear Tree P&R area, opposite Keble College. r Parks Rd please use one of the following bus stops: c Oxford Parkway 1 High Street Travel Shop e ster Pl 44-45 High Street J3 I1 I2 S1 E2 E6 Oxford, OX1 4AP Ashmolean St Johns towards: See overleaf for Museum Longwall St Oxford Bus Company city2 detailed maps C5 Balliol High St 2 Debenhams Travel Shop towards Summertown & Kidlington Magdalen Street Trinity Top Floor, Debenhams C4 Holywell Street C1 Street Walton Beaumont Street C3 Magdalen Street 2 Oxford, OX1 3AA C2 Sheldonian Theatre Rail Station Gloucester Green B3 C1 Broad Street city3 B7 B2 Tourist Information Centre towards Iffley Road & Rose Hill Coach Station B6 3 Bodleian Library B1 3 15-16 Broad Street B5 A1 Turl Street R5 R6 George StreetA2 K2 D4 R1 R2 R3 R4 A3 All Souls Oxford, OX1 3AS New Inn Hall Street Ship Street A5 Radcliffe visitoxfordandoxfordshire.com city4 Hythe Bridge St Camera Queens D0 K1 K2 K3 K4 K5 Pitt Rivers Museum F1 Cornmarket Street towards Wood Farm D1 Market Street 1 Park End St D2 Clarendon 4 South Parks Road R2 F1 D1 M1 S2 G1 K3 Frideswide Sq D3 Covered L1 Bonn Centre Oxford, OX1 3PP New Road Market J2 J1 * F2 F3 Square High Street J3 towards Rail Station & Abingdon E6 www.prm.ox.ac.uk towards: E5 D4 7 towards: E4 I1 J3 I1 S1 E2 F2 Botley St Thomas Street -

F4 URS Protected Species Report 2012

Homes and Communities Agency Northstowe Phase 2 Environmental Statement F4 URS Protected Species Report 2012 Page F4 | | Northstowe Protected Species Report July 2013 47062979 Prepared for: Homes and Communities Agency UNITED KINGDOM & IRELAND REVISION RECORD Rev Date Details Prepared by Reviewed by Approved by 2 December Version 2 Rachel Holmes Steve Muddiman Steve Muddiman 2012 Principal Associate Associate Environmental Ecologist Ecologist Consultant 4 January Version 4 Rachel Holmes Steve Muddiman Steve Muddiman 2013 Principal Associate Associate Environmental Ecologist Ecologist Consultant 5 July 2013 Version 5 Rachel Holmes Steve Muddiman Steve Muddiman Principal Associate Associate Environmental Ecologist Ecologist Consultant URS Infrastructure & Environment UK Limited St George’s House, 5 St George’s Road Wimbledon, London SW19 4DR United Kingdom PROTECTED SPECIES REPORT 2 2013 Limitations URS Infrastructure & Environment UK Limited (“URS”) has prepared this Report for the sole use of Homes and Communities Agency (“Client”) in accordance with the Agreement under which our services were performed (proposal dated 7th April and 23 rd July 2012). No other warranty, expressed or implied, is made as to the professional advice included in this Report or any other services provided by URS. This Report is confidential and may not be disclosed by the Client nor relied upon by any other party without the prior and express written agreement of URS. The conclusions and recommendations contained in this Report are based upon information provided by others and upon the assumption that all relevant information has been provided by those parties from whom it has been requested and that such information is accurate. Information obtained by URS has not been independently verified by URS, unless otherwise stated in the Report. -

Dipterists Forum

BULLETIN OF THE Dipterists Forum Bulletin No. 76 Autumn 2013 Affiliated to the British Entomological and Natural History Society Bulletin No. 76 Autumn 2013 ISSN 1358-5029 Editorial panel Bulletin Editor Darwyn Sumner Assistant Editor Judy Webb Dipterists Forum Officers Chairman Martin Drake Vice Chairman Stuart Ball Secretary John Kramer Meetings Treasurer Howard Bentley Please use the Booking Form included in this Bulletin or downloaded from our Membership Sec. John Showers website Field Meetings Sec. Roger Morris Field Meetings Indoor Meetings Sec. Duncan Sivell Roger Morris 7 Vine Street, Stamford, Lincolnshire PE9 1QE Publicity Officer Erica McAlister [email protected] Conservation Officer Rob Wolton Workshops & Indoor Meetings Organiser Duncan Sivell Ordinary Members Natural History Museum, Cromwell Road, London, SW7 5BD [email protected] Chris Spilling, Malcolm Smart, Mick Parker Nathan Medd, John Ismay, vacancy Bulletin contributions Unelected Members Please refer to guide notes in this Bulletin for details of how to contribute and send your material to both of the following: Dipterists Digest Editor Peter Chandler Dipterists Bulletin Editor Darwyn Sumner Secretary 122, Link Road, Anstey, Charnwood, Leicestershire LE7 7BX. John Kramer Tel. 0116 212 5075 31 Ash Tree Road, Oadby, Leicester, Leicestershire, LE2 5TE. [email protected] [email protected] Assistant Editor Treasurer Judy Webb Howard Bentley 2 Dorchester Court, Blenheim Road, Kidlington, Oxon. OX5 2JT. 37, Biddenden Close, Bearsted, Maidstone, Kent. ME15 8JP Tel. 01865 377487 Tel. 01622 739452 [email protected] [email protected] Conservation Dipterists Digest contributions Robert Wolton Locks Park Farm, Hatherleigh, Oakhampton, Devon EX20 3LZ Dipterists Digest Editor Tel. -

A Preliminary Invertebrate Survey

Crane Park, Twickenham: preliminary invertebrate survey. Richard A. Jones. 2010 Crane Park, Twickenham: preliminary invertebrate survey BY RICHARD A. JONES F.R.E.S., F.L.S. 135 Friern Road, East Dulwich, London SE22 0AZ CONTENTS Summary . 2 Introduction . 3 Methods . 3 Site visits . 3 Site compartments . 3 Location and collection of specimens . 4 Taxonomic coverage . 4 Survey results . 4 General . 4 Noteworthy species . 5 Discussion . 9 Woodlands . 9 Open grassland . 10 River bank . 10 Compartment breakdown . 10 Conclusion . 11 References . 12 Species list . 13 Page 1 Crane Park, Twickenham: preliminary invertebrate survey. Richard A. Jones. 2010 Crane Park, Twickenham: preliminary invertebrate survey BY RICHARD A. JONES F.R.E.S., F.L.S. 135 Friern Road, East Dulwich, London SE22 0AZ SUMMARY An invertebrate survey of Crane Park in Twickenham was commissioned by the London Borough of Richmond to establish a baseline fauna list. Site visits were made on 12 May, 18 June, 6 and 20 September 2010. Several unusual and scarce insects were found. These included: Agrilus sinuatus, a nationally scarce jewel beetle that breeds in hawthorn Argiope bruennichi, the wasp spider, recently starting to spread in London Dasytes plumbeus, a nationally scarce beetle found in grassy places Ectemnius ruficornis, a nationally scarce wasp which nests in dead timber Elodia ambulatoria, a nationally rare fly thought to be a parasitoid of tineid moths breeding in bracket fungi Eustalomyia hilaris, a nationally rare fly that breeds in wasp burrows in dead timber -

Badgers - Numbers, Gardens and Public Attitudes in Iffley Fields

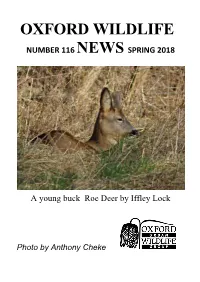

OXFORD WILDLIFE NUMBER 116 NEWS SPRING 2018 A young buck Roe Deer by Iffley Lock Photo by Anthony Cheke NEWS FROM BOUNDARY BROOK NATURE PARK The hedge around the Nature Park between us and the allotment area had grown a lot during the last year and was encroaching on the allotment site. The allotment holders understandably were not happy about this and were prepared to get a professional group to do the work. This would have been very expensive for us and nobody volunteered to help with the clearance. Very nobly Alan Hart, the Warden, made a start on this great task and made tremendous progress. Then the snow came. Alan could not even get into Oxford let alone cut the hedge! He has now done more but there is still a lot to be done if anyone feels willing to help, please contact him. His phone numbers are on the back page of this newsletter. PAST EVENTS Sadly, the January day we chose for our winter walk in University Parks to the river was literally a “wash-out”! On the day, in case the rain decided to stop, I turned up at the meeting place at the time we’d chosen but as I suspected nobody had turned out and the rain didn’t stop. Maybe we could schedule it again. It would be useful if you could let me know if you would have come if the sun had been shining. If not are there any other places in the Oxford area you’d like to explore. Please let me know if so. -

New Data on the Sawfly Fauna of Corsica with the Description of a New Species Pontania Cyrnea Sp.N

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Nachrichtenblatt der Bayerischen Entomologen Jahr/Year: 2005 Band/Volume: 054 Autor(en)/Author(s): Liston Andrew D., Späth Jochen Artikel/Article: New data on the sawfly fauna of Corsica with the description of a new species Pontania cyrnea sp.n. (Hymenoptera, Symphyta) 2-7 © Münchner Ent. Ges., download www.biologiezentrum.at NachrBl. bayer. Ent. 54 (1 /2), 2005 New data on the sawfly fauna of Corsica with the description of a new species Pontania cyrnea sp. n. (Hymenoptera, Symphyta) A. D. LISTON & J. SPÄTH Abstract Records of 38 taxa of Symphyta collected recently by the authors in Corsica are presented. 15 identified species are additions to the known Corsican fauna. Pontania cyrnea sp. n. is described and compared with the morphologically similar P. joergcnseni ENSLIN. The family Xyelidae is recorded for the first time on the island. A total of 71 symphytan species are now known from Corsica. Introduction CHEVIN (1999) published a list of 56 species of sawflies and other Symphyta (woodwasps, orus- sids) from Corsica. His paper is based mainly on material made available to him by specialists in other insect groups who have collected there. He also included data on specimens from Corsica in the Muséum national d'Histoire naturelle (Paris), and mentioned a few taxa already recorded in papers by other symphytologists. The island had previously been visited by a single sawfly specialist, who examined only the leaf-mining species (BUHR 1941). In spring 2004 the junior author stated his intent to collect Symphyta in Corsica. -

Additions, Deletions and Corrections to An

Bulletin of the Irish Biogeographical Society No. 36 (2012) ADDITIONS, DELETIONS AND CORRECTIONS TO AN ANNOTATED CHECKLIST OF THE IRISH BUTTERFLIES AND MOTHS (LEPIDOPTERA) WITH A CONCISE CHECKLIST OF IRISH SPECIES AND ELACHISTA BIATOMELLA (STAINTON, 1848) NEW TO IRELAND K. G. M. Bond1 and J. P. O’Connor2 1Department of Zoology and Animal Ecology, School of BEES, University College Cork, Distillery Fields, North Mall, Cork, Ireland. e-mail: <[email protected]> 2Emeritus Entomologist, National Museum of Ireland, Kildare Street, Dublin 2, Ireland. Abstract Additions, deletions and corrections are made to the Irish checklist of butterflies and moths (Lepidoptera). Elachista biatomella (Stainton, 1848) is added to the Irish list. The total number of confirmed Irish species of Lepidoptera now stands at 1480. Key words: Lepidoptera, additions, deletions, corrections, Irish list, Elachista biatomella Introduction Bond, Nash and O’Connor (2006) provided a checklist of the Irish Lepidoptera. Since its publication, many new discoveries have been made and are reported here. In addition, several deletions have been made. A concise and updated checklist is provided. The following abbreviations are used in the text: BM(NH) – The Natural History Museum, London; NMINH – National Museum of Ireland, Natural History, Dublin. The total number of confirmed Irish species now stands at 1480, an addition of 68 since Bond et al. (2006). Taxonomic arrangement As a result of recent systematic research, it has been necessary to replace the arrangement familiar to British and Irish Lepidopterists by the Fauna Europaea [FE] system used by Karsholt 60 Bulletin of the Irish Biogeographical Society No. 36 (2012) and Razowski, which is widely used in continental Europe. -

Sawflies (Hym.: Symphyta) of Hayk Mirzayans Insect Museum with Four

Journal of Entomological Society of Iran 2018, 37(4), 381404 ﻧﺎﻣﻪ اﻧﺠﻤﻦ ﺣﺸﺮهﺷﻨﺎﺳﯽ اﯾﺮان -404 381 ,(4)37 ,1396 Doi: 10.22117/jesi.2018.115354 Sawflies (Hym.: Symphyta) of Hayk Mirzayans Insect Museum with four new records for the fauna of Iran Mohammad Khayrandish1&* & Ebrahim Ebrahimi2 1- Department of Plant Protection, Faculty of Agriculture, Shahid Bahonar University, Kerman, Iran & 2- Insect Taxonomy Research Department, Iranian Research Institute of Plant Protection, Agricultural Research, Education and Extension Organization (AREEO), Tehran 19395-1454, Iran. *Corresponding author, E-mail: [email protected] Abstract A total of 60 species of Symphyta were identified and listed from the Hayk Mirzayans Insect Museum, Iran, of which the species Abia candens Konow, 1887; Pristiphora appendiculata (Hartig, 1837); Macrophya chrysura (Klug, 1817) and Tenthredopsis nassata (Geoffroy, 1785) are newly recorded from Iran. Distribution data and host plants are here presented for 37 sawfly species. Key words: Symphyta, Tenthredinidae, Argidae, sawflies, Iran. زﻧﺒﻮرﻫﺎي ﺗﺨﻢرﯾﺰ ارهاي (Hym.: Symphyta) ﻣﻮﺟﻮد در ﻣﻮزه ﺣﺸﺮات ﻫﺎﯾﮏ ﻣﯿﺮزاﯾﺎﻧﺲ ﺑﺎ ﮔﺰارش ﭼﻬﺎر رﮐﻮرد ﺟﺪﯾﺪ ﺑﺮاي ﻓﻮن اﯾﺮان ﻣﺤﻤﺪ ﺧﯿﺮاﻧﺪﯾﺶ1و* و اﺑﺮاﻫﯿﻢ اﺑﺮاﻫﯿﻤﯽ2 1- ﮔﺮوه ﮔﯿﺎهﭘﺰﺷﮑﯽ، داﻧﺸﮑﺪه ﮐﺸﺎورزي، داﻧﺸﮕﺎه ﺷﻬﯿﺪ ﺑﺎﻫﻨﺮ، ﮐﺮﻣﺎن و 2- ﺑﺨﺶ ﺗﺤﻘﯿﻘﺎت ردهﺑﻨﺪي ﺣﺸﺮات، ﻣﺆﺳﺴﻪ ﺗﺤﻘﯿﻘﺎت ﮔﯿﺎهﭘﺰﺷﮑﯽ اﯾﺮان، ﺳﺎزﻣﺎن ﺗﺤﻘﯿﻘﺎت، ﺗﺮوﯾﺞ و آﻣﻮزش ﮐﺸﺎورزي، ﺗﻬﺮان. * ﻣﺴﺌﻮل ﻣﮑﺎﺗﺒﺎت، ﭘﺴﺖ اﻟﮑﺘﺮوﻧﯿﮑﯽ: [email protected] ﭼﮑﯿﺪه درﻣﺠﻤﻮع 60 ﮔﻮﻧﻪ از زﻧﺒﻮرﻫﺎي ﺗﺨﻢرﯾﺰ ارهاي از ﻣﻮزه ﺣﺸﺮات ﻫﺎﯾﮏ ﻣﯿﺮزاﯾﺎﻧﺲ، اﯾﺮان، ﺑﺮرﺳﯽ و ﺷﻨﺎﺳﺎﯾﯽ ﺷﺪﻧﺪ ﮐﻪ ﮔﻮﻧﻪﻫﺎي Macrophya chrysura ،Pristiphora appendiculata (Hartig, 1837) ،Abia candens Konow, 1887 (Klug, 1817) و (Tenthredopsis nassata (Geoffroy, 1785 ﺑﺮاي اوﻟﯿﻦ ﺑﺎر از اﯾﺮان ﮔﺰارش ﺷﺪهاﻧﺪ. اﻃﻼﻋﺎت ﻣﺮﺑﻮط ﺑﻪ ﭘﺮاﮐﻨﺶ و ﮔﯿﺎﻫﺎن ﻣﯿﺰﺑﺎن 37 ﮔﻮﻧﻪ از زﻧﺒﻮرﻫﺎي ﺗﺨﻢرﯾﺰ ارهاي اراﺋﻪ ﺷﺪه اﺳﺖ. -

2-25 May 2020 Scenes and Murals Wallpaper AMAZING ART in WONDERFUL PLACES ACROSS OXFORDSHIRE

2-25 May 2020 Scenes and Murals Wallpaper AMAZING ART IN WONDERFUL PLACES ACROSS OXFORDSHIRE. All free to enter. Designers Guild is proud to support Oxfordshire Artweeks Available throughout Oxfordshire including The Curtain Shop 01865 553405 Anne Haimes Interiors 01491 411424 Stella Mannering & Company 01993 870599 Griffi n Interiors 01235 847135 Lucy Harrison Fabric | Wallpaper | Paint | Furniture | Accessories Interiors www.artweeks.org 07791 248339 Fairfax Interiors designersguild.com FREE FESTIVAL GUIDE 01608 685301 & ARTIST DIRECTORY Fresh Works Paintings by Elaine Kazimierzcuk 7 - 30 May 2020 The North Wall, South Parade, Oxford OX2 7JN St Edward’s School is the principal sponsor of The North Wall’s innovative public programme of theatre, 4 Oxfordshire Artweeks music, art exhibitions,www.artweeks.org dance and talks.1 THANKS WELCOME Oxfordshire Artweeks 2020 Artweeks is a not-for-profit organisation and relies upon the generous Welcome to the 38th Oxfordshire Artweeks festival during support of many people to whom we’re most grateful as we bring this which you can see, for free, amazing art in hundreds of celebration of the visual arts to you. These include: from Oxfordshire Artweeks 2020 Oxfordshire from wonderful places, in artists’ homes and studios, along village trails and city streets, in galleries and gardens Patrons: Will Gompertz, Mark Haddon, Janina Ramirez across the county. It is your chance, whether a seasoned Artweeks 2020 to Oxfordshire art enthusiast or an interested newcomer, to enjoy art in Board members: Anna Dillon, Caroline Harben, Kate Hipkiss, Wendy a relaxed way, to meet the makers and see their creative Newhofer, Hannah Newton (Chair), Sue Side, Jane Strother and Robin talent in action. -

Coleoptera: Lycidae, Lampyridae, Cantharidae, Oedemeridae) Less Studied in Azerbaijan

Artvin Çoruh Üniversitesi Artvin Coruh University Orman Fakültesi Dergisi Journal of Forestry Faculty ISSN:2146-1880, e-ISSN: 2146-698X ISSN:2146-1880, e-ISSN: 2146-698X Cilt: 15, Sayı:1, Sayfa: 1-8, Nisan 2014 Vol: 15, Issue: 1, Pages: 1-8, April 2014 http://edergi.artvin.edu.tr Species Composition of Chortobiont Beetles (Coleoptera: Lycidae, Lampyridae, Cantharidae, Oedemeridae) Less Studied In Azerbaijan Ilhama Gudrat KERİMOVA, Ellada Aghamelik HUSEYNOVA Laboratory of Ecology and Physiology of Insects, Azerbaijan National Academy of Sciences, Baku, Azerbaijan Article Info: Research article Corresponding author: Ilhama Gudrat Kerimova, e-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT The paper contains information about hortobiont beetle species from families Lycidae, Lampyridae, Cantharidae and Oedemeridae less studied in Azerbaijan. Check list of species distributed in Azerbaijan is presented basing on own materials and literature data. Materials were collected in the Greater Casucasus, the Kur River lowland, Lankaran and Middle Araz (Nakhchivan) natural regions and was recorded 1 species from Lycidae, 2 species from Lampyridae, 4 species from Cantharidae and 4 species from Oedemeridae families. From them Oedemera virescens (Linnaeus, 1767), Cantharis rufa Linnaeus, 1758, Cantharis melaspis Chevrolat, 1854, Cantharis melaspoides Wittmer, 1971 and Metacantharis clypeata Illiger, 1798 are new to Azerbaijan fauna. Key words: Lycidae, Lampyridae, Cantharidae, Oedemeridae, fauna, hortobiont Azerbaycan’da Az Çalışılmış Hortobiont Böcek Gruplarının (Coleoptera: Lycidae, Lampyridae, Cantharidae, Oedemeridae) Tür Kompozisyonları Eser Bilgisi: Araştırma makalesi Sorumlu yazar: Ilhama Gudrat Kerimova, e-mail: [email protected] ÖZET Bu araştırmada Azerbaycan’da az çalışılmış Lycidae, Lampyridae, Cantharidae ve Oedemeridae ailelerine ait olan hortobiont böcekler konusunda bilgi verilmiştir. Azerbaycan’da kayda alınmış bu gruplara ait böceklerin listesi hem literatür bilgileri hem de şahsi materyaller doğrultusunda sunulmuştur. -

Oxford/Cherwell/South Oxfordshire/Vale Of

Government Com m ission For Englan^f» S d Report No.581 Principal Area Boundary Review Consequential Electora Arrangements') C TY OF OXFOR ) ) ST } CIS OF CH SOUTH OXFOR )S VALE OF W TE HORSE LOCAL GOVEHNlfEBT BOUNDARY COMMISSION t'OH ENGLAND REPORT NO .5G1 LOCAL GOVERNMENT BOUNDARY COMMISSION FOR ENGLAND CHAIRMAN Mr G J Ellerton CMC MBE DEPUTY CHAIRMAN Mr J G Powell CBE FRICS FSVA Members Professor G E Cherry BA FRTPI FRICS Mr K F J Ennals CB Mr G R Prentice Mrs H R V Sarkany Mr B Scholes OBE THE RT. HON. NICHOLAS RIDLEY MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR THE ENVIRONMENT PRINCIPAL AREA BOUNDARY REVIEW: CITY OF OXFORD/DISTRICTS OF CHERWELL/SOUTH OXFORDSHIRE/VALE OF WHITE HORSE FINAL PROPOSALS FOR CHANGES TO ELECTORAL ARRANGEMENTS CONSEQUENTIAL TO PROPOSED BOUNDARY CHANGES INTRODUCTION 1. On 18 June 1987 we submitted to you our Report No. 536 containing our final proposals for the realignment of the boundary between the City of Oxford and the Districts of Cherwell, South Oxfordshire and Vale of White Horse in the County of Oxfordshire. 2. In our report we pointed out that we had made no proposals to deal with the electoral consequences of the proposed boundary changes and that our final proposals for consequential changes to electoral arrangements would be the subject of a separate report to you. In view of the nature and extent of the electoral consequences, we had decided that they ought to be advertised separately in order to give local authorities and residents affected by them a full opportunity to comment.