Klez-Cd-Book-7.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

VOCAL 78 Rpm Discs Minimum Bid As Indicated Per Item

VOCAL 78 rpm Discs Minimum bid as indicated per item. Listings “Just about 1-2” should be considered as mint and “Cons. 2” with just the slightest marks. For collectors searching top copies, you’ve come to the right place! The further we get from the time of production (in many cases now 100 years or more), the more difficult it is to find such excellent extant pressings. Some are actually from mint dealer stocks and others the result of having improved copies via dozens of collections purchased over the past fifty years. * * * For those looking for the best sound via modern reproduction, those items marked “late” are usually of high quality shellac, pressed in the 1950-55 period. A number of items in this particular catalogue are excellent pressings from that era. * * * Please keep in mind that the minimum bids are in U.S. Dollars, a benefit to most collectors. * * * “Text label on verso.” For a brief period (1912-14), Victor pressed silver-on-black labels on the reverse sides of some of their single-faced recordings, usually with a translation of the text or similarly related comments. BESSIE ABOTT [s]. Riverdale, NY, 1878-New York, 1919. Following the death of her father which left her family penniless, Bessie and her sister Jessie (born Pickens) formed a vaudeville sister vocal act, accompanying themselves on banjo and guitar. Upon the recommendation of Jean de Reszke, who heard them by chance, Bessie began operatic training with Frida Ashforth. She subsequently studied with de Reszke him- self and appeared with him at the Paris Opéra, making her debut as Gounod’s Juliette. -

559188 Bk Harbison US

AMERICAN CLASSICS Ernst TOCH Violin Sonata No. 1 • Cello Sonata Divertimento • String Trio • Adagio elegiaco Spectrum Concerts Berlin Ernst Toch (1887-1964) Music from the 1920s: the passages of heightened motion and power, the ebbing Violin Sonata No. 1 • Cello Sonata • Divertimento • String Trio • Adagio elegiaco the Divertimento and the Cello Sonata away, the way in which the movement dissolves at the end. Classical forms are here no longer normative; they Survey of the Life of a Creative Artist From Toch’s Early Works: The duo Divertimentos, Op. 37, and the Cello Sonata, have become the subject of the composition. Violin Sonata No. 1, Op. 21 Op. 50 , were written in 1927 and 1929, during what was Toch headed the central movements of both works This is Spectrum Concerts Berlin’s third recording of probably Toch’s most productive period. In them, he “intermezzo”, but they are anything but short intermezzos chamber music by Ernst Toch. Its musicians give concerts The First Violin Sonata, which Toch’s friends used to refer engaged in a creative dialogue with his artistic milieu in or interludes. Toch employs the term in the late above all in Berlin and New York and are passionate to as “Brahms’s Fourth”, was a product of this two ways: in the music itself and in the dedications of the Brahmsian sense, as a deliberate understatement, about exploring and highlighting the cultural links between understanding of tradition. Two reasons lie behind its pieces. The Cello Sonata he dedicated to Emanuel indicating a particular limitation of the musical material. -

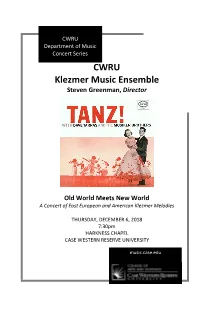

Klezmer Program 12.06.18

CWRU DepArtment oF MusIc Concert SerIes CWRU Klezmer Music Ensemble Steven Greenman, Director Old World Meets New World A Concert of East European and American Klezmer Melodies THURSDAY, DECEMBER 6, 2018 7:30pm HARKNESS CHAPEL CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY musIc.cAse.edu Welcome to Florence-Harkness Memorial Chapel RESTROOMS Women’s And men’s restrooms Are locAted on the mAIn level oF the buildIng. PAGERS, CELL PHONES, COMPUTERS, IPADS AND LISTENING DEVICES As A courtesy to the perFormers And AttendIng AudIence members, pleAse power oFF All electronic And mechanicAl devIces, Including pagers, cellulAr telephones, computers IPAds, wrIst wAtch AlArms, etc. prIor to the stArt oF the concert. PHOTOGRAPHY, VIDEO AND RECORDING DEVICES As A courtesy to the perFormers And AudIence members, photogrAphy And vIdeogrAphy Is strIctly prohibIted durIng the perFormAnce. FACILITY GUIDELINES In order to preserve the beAuty And cleAnlIness oF the hAll, no Food or beverAge, Including wAter, Is permItted. A DrInkIng FountAIn Is locAted neAr the restrooms beside the classroom. IN THE EVENT OF AN EMERGENCY ContAct An usher or A member oF the house stAFF IF you requIre medIcAl AssIstAnce. Emergency exIts Are cleArly marked throughout the buIldIng. Ushers And house staFF wIll provIde Instruction In the event oF An emergency. musIc.cAse.edu/FAcIlItIes/Florence-harkness-memorIAl-chApel/ Program “Rumania” Bulgar AlexAnder OlshAnetsky -from the recordIng Tanz! With Dave Tarras and the Musiker Brothers - 1955 Chused’l #10 from International HeBrew Wedding Music (“HAsIdIc DAnce #10) by W. KostAkowsky - 1916 Dem Trisker Rebn’s Khosid TrAdItIonAl/DAve TArrAs (“The TrIsker Rebbe’s DAnce”) Recorded - 1925 Yiddish Bulgar Max EpsteIn (“JewIsh BulgAr”) Recorded wIth the HymIe JAcobson OrchestrA - 1947 Romanian Fantasy Pt. -

Klezmer Syllabus Spring 2014

Syllabus MUEN 3640: UVA Klezmer Ensemble Class number 21122 Spring 2014 Prof.: Joel Rubin e-mail: [email protected] phone: (434) 882-3161 Time and location: Mondays and Wednesdays 7:30-9:30 pm, Old Cabell Hall Room 113 Office: 207 Old Cabell Hall, office hours M 12:30-1:30 pm or by appointment Prerequisite: Intermediate to advanced skill on an instrument or voice (admission by audition at first class, Mon., Jan. 13, 2014 or by appointment) Special events this semester: Klezmer Workshop with Alan Bern, Sunday, Mar. 23, 11 am - 2 pm, Old Cabell room 107 Extra rehearsals Sun. Mar. 23, 6-9 pm, Old Cabell room 113 and Tues. Mar. 25, 7-10 pm, Old Cabell 113. Concert Thurs. Mar. 27, 8 pm in Old Cabell (sound check: 6 pm) Recording sessions in conjunction with Mead Endowment: in April, tba Description: Under the direction of Director of Music Performance and acclaimed clarinetist and ethnomusicologist Joel Rubin, the UVA Klezmer Ensemble focuses on the music of the klezmorim, the Jewish professional instrumentalists of Eastern Europe, as well as related eastern European traditions. The ensemble is made up of both undergraduate and graduate students, faculty, alumni, and other members of the greater Central Virginia community. The UVA Klezmer Ensemble is committed to ethnic, racial, cultural and religious diversity. Current and recent members have backgrounds from the US, Russia, Israel, Lebanon, Armenia, Iran, and India, with religious backgrounds ranging from Jewish to Christian, Hindu and Muslim. It is dedicated to exploring klezmer and other Jewish musical traditions from the 18th century to the present. -

THE EXPEDITIONS of the VICTOR TALKING MACHINE COMPANY THROUGH LATIN AMERICA, 1903-1926 a Dissertation

RECORDING STUDIOS ON TOUR: THE EXPEDITIONS OF THE VICTOR TALKING MACHINE COMPANY THROUGH LATIN AMERICA, 1903-1926 A Dissertation presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Sergio Daniel Ospina Romero May 2019 © 2019 Sergio Daniel Ospina Romero ii RECORDING STUDIOS ON TOUR: THE EXPEDITIONS OF THE VICTOR TALKING MACHINE THROUGH LATIN AMERICA, 1903-1926 Sergio Daniel Ospina Romero, PhD Cornell University, 2019 During the early twentieth century, recording technicians travelled around the world on behalf of the multinational recording companies. Producing recordings with vernacular repertoires not only became an effective way to open local markets for the talking machines that these same companies were manufacturing. It also allowed for an unprecedented global circulation of local musics. This dissertation focuses on the recording expeditions lead by the Victor Talking Machine Company through several cities in Latin America during the acoustic era. Drawing from untapped archival material, including the daily ledgers of the expeditions, the following pages offer the first comprehensive history of these expeditions while focusing on five areas of analysis: the globalization of recorded sound, the imperial and transcultural dynamics in the itinerant recording ventures of the industry, the interventions of “recording scouts” for the production of acoustic records, the sounding events recorded during the expeditions, and the transnational circulation of these recordings. I argue that rather than a marginal side of the music industry or a rudimentary operation, as it has been usually presented hitherto in many histories of the phonograph, sound recording during the acoustic era was a central and intricate area in the business; and that the international ventures of recording companies before 1925 set the conditions of possibility for the consolidation of iii media entertainment as a defining aspect of consumer culture worldwide through the twentieth century. -

Klezmer Dances

Klezmer Dances Alexandrovsky Valts (all around the circle of fifths, Mazel Tov Mekhutonim (congratulations for the in-law trad., Arr. WU), tutti, 1st performance 9.2.10 people, rather slow, Abe Schwartz, transcr. Jacobs) (2:39) [Maxwell Street Klezmer Band, Chicago. Publ. Araber tants (Naftule Brandwein 1889-1963, arr. WU, Tara Music] extremely polyphonic), soloist Daniëlle de Jong, sopra- no sax; five clarinets, 1st performance 11.5.12 Moritzpolka (trad. Polish-Jewish, arr. WU), soloist Mo- ritz Brößler, bass clarinet / clarinet, Anke Saeger, Bulgar-Trilogy (trad., Arr. WU, unfinished), tutti Tenor sax, tutti, 3:30, 1st performance 9.11.14 Varshaver freylekhs (trad., arr. WU), soloist Claudia Oy tate / Ot azoy (Lt. Joseph Frankel‘s Orchestra 1919 Schumann, clarinet / Der heyser bulgar (the hot B., / Shloimke Beckerman and Abe Schwartz Orchestra Naftule Brandwein, Arr. WU), soloist Carsten Fette, 1923, arr. WU – two pieces during which the band sang clarinet, 1st performances 11.3.12 / 9.11.14 unexpectedly…), soloists Katharina Müller and Sabine Freylakhs-Trilogy (three dances with temperament, Pelzer, soprano recorders; tutti, 1st perf. 28.4.13 (3:51) trad., Arr. WU), tutti (4:00) Patsh Tantz (trad., arr. KlezPO), tutti, 1st perf. 10.11.09 Freylekhs fun der khupe (dance under the wedding Serba din New York (Romaneasca Orch. = Abe canopee, Kandel‘s Orchestra ca. 1920, transcr. Koff- Schwartz‘s Orchestra, transcr. Jacobs, arr. Juri Bo- man) / Kolomeike (dance from the West Ukraine, kov) / Ruski Sher (trad., arr. Yoelin) / Lebedik un trad., arr. Margolis), solo Howard Schultens, banjo freylekh (Abe Schwartz, arr. Juri Bokov / Koffman) (4:36) [Maxwell Street Klezmer Band, Chicago. -

To Play Jewish Again: Roots, Counterculture, and the Klezmer Revival Claire Marissa Gogan Thesis Submitted to the Faculty Of

To Play Jewish Again: Roots, Counterculture, and the Klezmer Revival Claire Marissa Gogan Thesis submitted to the faculty of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts In History David P. Cline, Co-Chair Brett L. Shadle, Co-Chair Rachel B. Gross 4 May 2016 Blacksburg, Virginia Keywords: Identity, Klezmer, Jewish, 20th Century, Folk Revival Copyright 2016 by Claire M. Gogan To Play Jewish Again: Roots, Counterculture, and the Klezmer Revival Claire Gogan ABSTRACT Klezmer, a type of Eastern European Jewish secular music brought to the United States in the late 19th and early 20th century, originally functioned as accompaniment to Jewish wedding ritual celebrations. In the late 1970s, a group of primarily Jewish musicians sought inspiration for a renewal of this early 20th century American klezmer by mining 78 rpm records for influence, and also by seeking out living klezmer musicians as mentors. Why did a group of Jewish musicians in the 1970s through 1990s want to connect with artists and recordings from the early 20th century in order to “revive” this music? What did the music “do” for them and how did it contribute to their senses of both individual and collective identity? How did these musicians perceive the relationship between klezmer, Jewish culture, and Jewish religion? Finally, how was the genesis for the klezmer revival related to the social and cultural climate of its time? I argue that Jewish folk musicians revived klezmer music in the 1970s as a manifestation of both an existential search for authenticity, carrying over from the 1960s counterculture, and a manifestation of a 1970s trend toward ethnic cultural revival. -

Association for Jewish Studies

42ND ANNUAL CONFERENCE OF THE ASSOCIATION FOR JEWISH STUDIES DECEMBER 19– 21, 2010 WESTIN COPLEY PLACE BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS ASSOCIATION FOR JEWISH STUDIES C/O CENTER FOR JEWISH HISTORY 15 WEST 16TH STREET NEW YORK, NY 10011-6301 PHONE: (917) 606-8249 FAX: (917) 606-8222 E-MAIL: [email protected] www.ajsnet.org President AJS Staff Marsha Rozenblit, University of Maryland Rona Sheramy, Executive Director Vice President/Membership Karen Terry, Program and Membership and Outreach Coordinator Anita Norich, University of Michigan Natasha Perlis, Project Manager Vice President/Program Emma Barker, Conference and Program Derek Penslar, University of Toronto Associate Vice President/Publications Karin Kugel, Program Book Designer and Jeffrey Shandler, Rutgers University Webmaster Secretary/Treasurer Graphic Designer, Cover Jonathan Sarna, Brandeis University Ellen Nygaard The Association for Jewish Studies is a Constituent Society of The American Council of Learned Societies. The Association for Jewish Studies wishes to thank the Center for Jewish History and its constituent organizations—the American Jewish Historical Society, the American Sephardi Federation, the Leo Baeck Institute, the Yeshiva University Museum, and the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research— for providing the AJS with offi ce space at the Center for Jewish History. Cover credit: “Israelitish Synagogue, Warren Street,” in the Boston Almanac, 1854. American Jewish Historical Society, Boston, MA and New York, NY. Copyright © 2010 No portion of this publication may be reproduced by any means without the express written permission of the Association for Jewish Studies. The views expressed in advertisements herein are those of the advertisers and do not necessarily refl ect those of the Association for Jewish Studies. -

An Exploration of Extra-Musical Issues in the Music of Don Byron Steven Craig Becraft

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2005 An Exploration of Extra-Musical Issues in the Music of Don Byron Steven Craig Becraft Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC AN EXPLORATION OF EXTRA-MUSICAL ISSUES IN THE MUSIC OF DON BYRON By STEVEN CRAIG BECRAFT A Treatise submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Music Degree Awarded: Fall Semester, 2005 Copyright 2005 Steven Craig Becraft All Rights Reserved The members of the committee approve the treatise of Steven Craig Becraft defended on September 26, 2005. ____________________________ Frank Kowalsky Professor Directing Treatise ____________________________ Denise Von Glahn Outside Committee Member ____________________________ Jeffrey Keesecker Committee Member ____________________________ Patrick Meighan Committee Member The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS To Don Byron: Thank you for making such fascinating music. I thoroughly appreciate your artistic vision, your intellect, and your phenomenal technique as a clarinetist. The knowledge I have gained and the new perspective I have on music and society as a result of completing the research for this treatise has greatly impacted my life. I am grateful for the support of the Arkansas Federation of Music Clubs, especially Janine Tiner, Ruth Jordan, and Martha Rosenbaum for awarding me the 2005 Marie Smallwood Thomas Scholarship Award that helped with final tuition and travel expenses. My doctoral committee has been a great asset throughout the entire degree program. -

Klezmer Music, History, and Memory 1St Edition Ebook Free Download

KLEZMER MUSIC, HISTORY, AND MEMORY 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Zev Feldman | 9780190244514 | | | | | Klezmer Music, History, and Memory 1st edition PDF Book Its primary venue was the multi-day Jewish wedding, with its many ritual and processional melodies, its table music for listening, and its varied forms of Jewish dance. The second part of the collection examines the klezmer "revival" that began in the s. Krakow is not far from Auschwitz and each year, a March of the Living, which takes visitors on a walk from Auschwitz to the nearby Birkenau death camp, draws tens of thousands of participants. Its organizers did not shy from the topic. But, I continued, we don't celebrate the military victory. Some aspects of these Klezmer- feeling Cohen compositions, as rendered, were surely modern in some of the instruments used, but the distinctive Jewish Klezmer feel shines through, and arguably, these numbers by Cohen are the most widely-heard examples of Klezmer music in the modern era due to Cohen's prolific multi-generational appeal and status as a popular poet-songwriter-singer who was very popular on several continents in the Western World from the s until his death in Ornstein, the director of the Jewish Community Center, said that while the festival celebrates the past, he wants to help restore Jewish life to the city today. All About Jazz needs your support Donate. Until this can be accessed, Feldman's detailed study will remain the go-to work for anyone wishing to understand or explore this endlessly suggestive subject. With Chanukah now past, and the solstice just slipped, I am running out of time to post some thoughts about the holiday. -

Politics and Popular Culture: the Renaissance in Liberian Music, 1970-89

POLITICS AND POPULAR CULTURE: THE RENAISSANCE IN LIBERIAN MUSIC, 1970-89 By TIMOTHY D. NEVIN A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FUFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2010 1 © 2010 Timothy Nevin 2 To all the Liberian musicians who died during the war-- (Tecumsey Roberts, Robert Toe, Morris Dorley and many others) Rest in Peace 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank my parents and my uncle Frank for encouraging me to pursue graduate studies. My father’s dedication to intellectual pursuits and his life-long love of teaching have been constant inspirations to me. I would like to thank my Liberian wife, Debra Doeway for her patience in attempting to answer my thousand and one questions about Liberian social life and the time period “before the war.” I would like to thank Dr. Luise White, my dissertation advisor, for her guidance and intellectual rigor as well as Dr. Sue O’Brien for reading my manuscript and offering helpful suggestions. I would like to thank others who also read portions of my rough draft including Marissa Moorman. I would like to thank University of Florida’s Africana librarians Dan Reboussin and Peter Malanchuk for their kind assistance and instruction during my first semester of graduate school. I would like to acknowledge the many university libraries and public archives that welcomed me during my cross-country research adventure during the summer of 2007. These include, but are not limited to; Verlon Stone and the Liberian Collections Project at Indiana University, John Collins and the University of Ghana at East Legon, Northwestern University, Emory University, Brown University, New York University, the National Archives of Liberia, Dr. -

Klezmer: Music and Community in Twentieth-Century Jewish

Klezmer Hankus Netsky Klezmer Music and Community in Twentieth-Century Jewish Philadelphia TEMPLE UNIVERSITY PRESS Philadelphia • Rome • Tokyo TEMPLE UNIVERSITY PRESS Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19122 www . temple . edu / tempress Copyright © 2015 by Temple University— Of Th e Commonwealth System of Higher Education All rights reserved Published 2015 All reasonable attempts were made to locate the copyright holder for the cover illustration. If you believe you are the copyright holder, please contact Temple University Press, and the publisher will include appropriate ac know ledg ment in subsequent editions of the book. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Netsky, Hankus, author. Klezmer : music and community in twentieth- century Jewish Philadelphia / Hankus Netsky. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-4399-0903-4 (cloth : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-1-4399-0905-8 (e- book) 1. Klezmer music— Pennsylvania— Philadelphia—20th century— History and criticism. 2. Jewish musicians— Pennsylvania— Philadelphia—20th century— History and criticism. 3. Jews— Pennsylvania— Philadelphia— Music— History and criticism. 4. Klezmer music— Social aspects— Pennsylvania— Philadelphia— History—20th century. I. Title. ML3528.8.N48 2015 781.62'924074811— dc23 2014048496 Th e paper used in this publication meets the requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences— Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992 Printed in the United States of Ame rica 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Table