How to Fast Track Edinburgh's Trams

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Homewarts-Movie-Map-Guide2.Pdf

1 This guide will provide you with more detailed information such as addresses, route descriptions and other useful information for a convenient homewarts journey. As we did on homewarts.com, we will start in London. 2 Alohomora London .................................................................................................................................................. 6 London City ........................................................................................................................................ 7 Lambeth Bridge .................................................................................................................................... 9 Horse Guards Avenue ....................................................................................................................... 11 Great Scotland Yard....................................................................................................................... 13 Piccadilly Circus ............................................................................................................................. 15 Charing Cross Road ......................................................................................................................... 17 Australian High Commission ........................................................................................................ 18 St. Pancras and King’s Cross ........................................................................................................ 20 Claremont Square ........................................................................................................................... -

Local Transport Strategy Draft

Contents Executive Summary 1. Introduction 2. Vision and performance 3. Putting our customers first 4. Sustaining a thriving city 5. Protecting our environment 6. Road safety 7. Managing and maintaining our infrastructure 8. Travel planning, travel choices and marketing 9. Active travel 10. Public transport 11. Car and motorcycle travel 12. Car parking 13. Freight 14. Edinburgh’s connectivity 15. Making it happen Appendix 1 – Our indicators Appendix 2 – Plan and programme Appendix 3 – Policy documents Appendix 4 - References 1 Foreword "A developed country is not a place where the poor have cars. It's where the rich use public transport." Enrique Peñalosa, one time mayor of Bogota. The last ten years have seen achievements that Edinburgh can be proud of. We are the only city in Scotland that saw seen walking, cycling and public transport all strengthen their role between the 2001 and 2011 censuses. Edinburgh now boasts the highest share of travel to work in Scotland by each of foot, cycle and bus and the highest share in the UK for bus. We have also bucked Scottish and UK trends in car ownership; despite increasing affluence, a lower percentage of Edinburgh households owned a car in 2011 than 2001. The next five years promise to be an exciting time. We have delivered the first phase of the new Tram line, and can finally enjoy all its benefits. Transport for Edinburgh will be working to deliver increased integration and co-ordination of the wider public transport network. Edinburgh is joining the growing list of progressive UK cities putting people first through applying 20mph speed limits. -

Non-Executive Directors SRUC Board 2018

Non-Executive Directors SRUC Board 2018 1 CANDIDATE BRIEF Non-Executive Directors – SRUC Board Contents Page 3 Introduction and message from Chair of SRUC Board Page 3 SRUC – Overview, Background and Academic Strategy Page 4 SRUC’s Vision & Mission Page 5 SRUC Board and Governance Structure Page6 SRUC Governance Structure Page 7 The role of Non-Executive Director – SRUC Board Page 8 SRUC Divisions Page 10 Fees, term, location and message from Prof Christine Williams Page 11 Application Process Page 12 Links to Supplementary Information SRUC a Charitable company limited by guarantee, SC003712. Registered in Scotland No SC103046 2 Introduction SRUC is embarking on a mission to reposition itself for long-term sustainability and future growth by developing bold and ambitious strategies to reconnect agriculture, land-based activity, the environment and food supply to society. To place SRUC in the strongest possible position as we advance and develop our plans and to accelerate the pace of transformational change, the Board has agreed to the creation of two new Non-Executive Directors. The creation of these two roles presents opportunities to become involved and contribute to the future success of an organisation of strategic national importance at a period of exceptional change within the rural economy in Scotland and beyond. Sandy Cumming CBE Chair of the Board of Directors - SRUC SRUC – Overview and Background SRUC is a unique organisation founded on world class and sector-leading research, education and consultancy. As a Higher Education Institution, we have specialist expertise in Education and Research and offer unrivalled links with industry through our Agricultural Business Consultants. -

Edinburgh Tram Line One Environmental Statement Non

EDINBURGH TRAM LINE ONE ENVIRONMENTAL STATEMENT NON-TECHNICAL SUMMARY 1. Introduction This document is the Non-Technical Summary of the Environmental Statement (ES) for the Edinburgh Tram Line One. The full ES was published in December 2003, to accompany the deposit of a private Bill before the Scottish Parliament seeking authority to build and operate Line One. Edinburgh Tram Line One is a 15½ kilometre circular tram route serving central and north Edinburgh. It forms part of a network of three routes being promoted by the City of Edinburgh Council (CEC) through transport initiatives edinburgh (tie), a company set up to deliver several major public transport schemes over the next 10 to 15 years. The ES has been prepared for Line One in accordance with the standing orders of the Scottish Parliament and determinations by the Presiding Officer, which require that projects approved by private Act of Parliament must be subject to Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA). EIA in Scotland is governed by the Environmental Impact Assessment (Scotland) Regulations 1999 (S.I. 1999 No. 1). The information presented in the ES must be taken into account by Parliament in making its decision to authorise Line One. The ES must also be made available for comment by interested parties and any comments or representations they make must additionally be taken into account. The Non-Technical Summary has been prepared for the non-specialist reader to assist in understanding the project and the main environmental issues associated with it. It provides a summary of the information presented in the full ES, in particular describing: • the design of the project and the way it will be constructed and operated; • its impacts on the physical, natural and human environment; • the measures that will be undertaken to minimise these impacts. -

Item No 1.1 the City of Edinburgh Council

Item no 1.1 + + EDIN BVRG H THE CITY OF EDINBURGH COUNCIL Leader’s Report The City of Edinburgh Council 11 March 2010 1 Haiti Earthquake Disaster There has been an incredible response to the Edinburgh Disaster Response Committee (EDRC) emergency appeal to raise funds for the Haiti earthquake. Over f300,OOO has been raised. Through the international charity Mercy Corps, with its European HQ in Edinburgh, the funds will focus on the longer term, giving support to those affected by the earthquake to help rebuild their Iives . Several high profile fund raising events have taken place, including the sell out ‘Poets for Haiti’ event, led by the Poet Laureate Carol Ann Duffy and Don Paterson. This was an amazing event with a fantastic posse of poets giving their services for free to the delight of the audience at Scotland’s biggest ever poetry reading. Edinburgh Makar, Ron Butlin, was the first poet up, setting the scene with The Magicians of Edinburgh. What an excellent finale it was to the Edinburgh City of Literature “Carry a Poem” campaign. Other city organisations have also been involved in fund-raising including NHS Lothian, the University of Edinburgh, the Royal Bank of Scotland and staff within the Council. Over 20 schools across the city have used a variety of ways to help the campaign including ‘Hats for Haiti’ and ‘Pyjama Day for Haiti’ events and the donation of proceeds from school cafes. Much more is still required to support the longer-term rebuilding efforts in Haiti. Please support the appeal in any way that you can. -

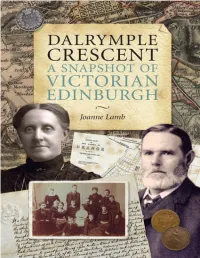

Dalrymple Crescent a Snapshot of Victorian Edinburgh

DALRYMPLE CRESCENT A SNAPSHOT OF VICTORIAN EDINBURGH Joanne Lamb ABOUT THE BOOK A cross-section of life in Edinburgh in the 19th century: This book focuses on a street - Dalrymple Crescent - during that fascinating time. Built in the middle of the 19th century, in this one street came to live eminent men in the field of medicine, science and academia, prosperous merchants and lawyers, The Church, which played such a dominant role in lives of the Victorians, was also well represented. Here were large families and single bachelors, marriages, births and deaths, and tragedies - including murder and bankruptcy. Some residents were drawn to the capital by its booming prosperity from all parts of Scotland, while others reflected the Scottish Diaspora. This book tells the story of the building of the Crescent, and of the people who lived there; and puts it in the context of Edinburgh in the latter half of the 19th century COPYRIGHT First published in 2011 by T & J LAMB, 9 Dalrymple Crescent, Edinburgh EH9 2NU www.dcedin.co.uk This digital edition published in 2020 Text copyright © Joanne Lamb 2011 Foreword copyright © Lord Cullen 2011 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form without the express written permission of the publisher. ISBN: 978-0-9566713-0-1 British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data. A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Designed and typeset by Mark Blackadder The publisher acknowledges a grant from THE GRANGE ASSOCIATION towards the publication of this book THIS DIGITAL EDITION Ten years ago I was completing the printed version of this book. -

Appointment of Chief Executive Officer

Appointment of Chief Executive Officer LIVINGSTON JAMES 2 Contents Message from the Chair 3 Our Organisation 5 The Opportunity 8 The Role 11 Candidate Profile 15 Recruitment Process 18 3 Message from the Chair Thank you for your interest in this opportunity with Transport for Edinburgh. This is a hugely important time for public transport in Edinburgh and the surrounding areas, with the new Borders Rail link, Edinburgh Airport undergoing significant passenger growth and expansion, and the new Edinburgh Gateway station at Gogar that will link passengers from the Fife line and North East Scotland to the airport, scheduled for completion in 2016. Transport for Edinburgh is central to this, and as we look to its future we are considering a long-term plan, in partnership with businesses and other key partners, which will continue to satisfy and service residents and visitors, improve transport links to the city centre and boost the local economy. Of course, Edinburgh is already a successful and competitive capital, and the city’s transport services play a vital role in that. But we must never rest on our laurels, especially as Edinburgh continues to grow in popularity as a place in which to live, work, invest, study and visit. We need to be prepared for that growth. There is work still to be done and a long way to travel but fortunately, there is much in our favour. Both bus and tram services achieved overall passenger satisfaction ratings of around 95% and impressive scores for value for money. Lothian Buses is highly valued, publicly- owned, profitable and returns an annual dividend which is invested in public services. -

Delegate Pre-‐Congress Information

Delegate Pre-Congress Information Congress Dates: Monday 25th – Friday 29th May 2015 Congress Venue: Edinburgh International Conference Centre (EICC) The Exchange, EdinBurgh, EH3 8EE Website: www.eicc.co.uk The XVth World Water Congress, hosted by the Scottish Government, presents a unique opportunity to associate with the dynamic international research community promoting the sustainable use of water resources across the globe as well as policymakers and the business community. The Congress provides the opportunity to attend a gathering of influential members of the water community – leading academics and policy makers – and raise the profile of your work The Congress will showcase a range of key issues including: water technology, governance, management and regulation as well as promoting Scotland’s contribution to global development and as a key destination for innovation and commerce with the potential to share and export its water expertise. JOINING INSTRUCTIONS: GUIDE TO CONTENTS Useful contact numbers p1 Registration at the Congress p2 Payment of Congress Fees p2 Programme Outline p2 Catering at the Congress p5 Congress facilities and services p5 Technical Visits p6 Social Programme p6 Transport in Edinburgh p8 Other Useful Information p9 Useful ContaCts Pre-congress +44 (0) 1738 828524 or [email protected] EICC Main Number +44 (0) 131 300 3000 WWC Registration Desk +44 (0) 131 519 4101 (registration open hours only) WWC Emergency Mobile Phone +44 (0) 7720 441776 World Water Congress Delegate Joining Instructions page 1 Registration E-tiCkets The week prior to the Congress you will be sent, by email, an e-ticket with a barcode. You should print this and bring it to Congress to facilitate speedy registration. -

2016 Air Quality Annual Progress Report (APR) for City of Edinburgh Council

City of Edinburgh Council 2016 Air Quality Annual Progress Report (APR) for City of Edinburgh Council In fulfilment of Part IV of the Environment Act 1995 Local Air Quality Management August 2016 LAQM Annual Progress Report 2016 City of Edinburgh Council Local Authority Janet Brown & Shauna Clarke Officer Department Place Planning & Transport, The City of Edinburgh Council, Waverley Court, Level G3, 4 East Address Market Street, Edinburgh EH8 8BG 0131 469 5742 & Telephone 0131 469 5058 [email protected] & E-mail [email protected] Report Reference APR16 ED_1 number Date August 2016 LAQM Annual Progress Report 2016 City of Edinburgh Council Executive Summary: Air Quality in Our Area Air Quality in City of Edinburgh Edinburgh has declared five Air Quality Management Areas (AQMAs) for the pollutant nitrogen dioxide (NO2). The maps of the AQMAs are available online at http://www.edinburgh.gov.uk/airquality An AQMA is required when a pollutant fails to meet air quality standards which are set by the Scottish Government. Road traffic is by far the greatest contributor to the high concentrations of NO2 in the city. Earlier assessment work has shown that the NO2 contribution from each vehicle class is different within the AQMAs. For example, cars were shown to contribute the most at Glasgow Road AQMA, with buses having the largest impact along some routes in the Central AQMA (London Road, Gorgie Road/Chesser, Princes Street) and HGVs having a significant impact at Bernard Street. Therefore, in order to improve air quality, it will be necessary to keep all motor vehicle classes under review. -

Notice of Meeting and Agenda

Transport and Environment Committee 10.00am, Tuesday 25 August 2015 Transport for Edinburgh – Annual Performance Review Item number Report number Executive/routine Wards All Executive summary Transport for Edinburgh (TfE) was established in 2013, as the parent company for both Lothian Buses and Edinburgh Tram. Edinburgh Tram is wholly owned by the City of Edinburgh Council and TfE holds the Council’s 91% share in Lothian Buses. This report reviews the performance of Transport for Edinburgh and it’s companies over the last 12 to 18 months and outlines their objectives for the next year. Links Coalition pledges P19, P50 Council outcomes CO8, CO22, CO26 Single Outcome Agreement SO1 Report Transport for Edinburgh – Annual Performance Review Recommendations 1.1 It is recommended that Transport and Environment Committee: 1.1.1 notes the contents of the report; 1.1.2 acknowledges the achievements of Transport for Edinburgh and it’s companies in particular the successful first year of operation of Tram, the many initiatives to support integration and the consequent increase in public transport patronage and high levels of customer satisfaction; 1.1.3 approves the objectives for Transport for Edinburgh and it’s companies; and; 1.1.4 agrees that officers work with Transport for Edinburgh to develop and agree specific targets, based on the objectives, for 2016 and report back to this Committee within two cycles. Background 2.1 At its meeting on 22 August 2013, the City of Edinburgh Council approved a new governance and corporate structures to provide governance, financial and shareholder controls over the Council’s transport companies – Lothian Buses and Edinburgh Tram (see Appendix 1). -

Edinburgh 2015 Action Plan

Air Quality Action Plan Progress with Actions 2015 For City of Edinburgh Council In fulfillment of Part IV of the Envionment Act 1995 – Local Air Quality Management August 2015 1 Local Authority Janet Brown Officer Local Authority Robbie Beattie Approval Department Services for Communities East Neighbourhood Centre, Address 101 Niddrie Mains Road, Edinburgh EH16 4DS Telephone 0131 469 5475 e-mail [email protected] Report Reference AQAPU2015 number Date August 2015 2 Executive Summary City of Edinburgh Council’s Air Quality Action Plan (AQAP) 2003 was revised in 2008 to remove congestion charging as an Action and to include the new Air Quality Management Area (AQMA) at St John’s Road. The council recognise that the current AQAP requires to be revised and this will include new AQMA declarations and extensions of the existing AQMAs This report provides an update on progress achieved for measures contained in the AQAP and City of Edinburgh Council’s Local Transport Strategy 2014 to 2019. The document requires to be read in conjunction with the Updating and Screening Assessment Report for City of Edinburgh Council 2015. This report concludes that steady progress has been achieved with respect to management of emissions from buses and freight via a voluntary approach. However, it is evident that the VERP proposed target of buses to be 100% Euro 5 by the end of October 2015 will not be achieved. Lothian Buses is the main local service provider in Edinburgh. It is anticipated that 66% of the fleet will be Euro 5 or better by December 2015. The company continues to deploy their cleanest vehicles on high- frequency routes that transit AQMAs. -

One City... Many Journeys January 2017 Foreword from City of Edinburgh Council Leader and Chief Executive

Strategy for Delivery 2017-2021 one city... many journeys January 2017 Foreword from City of Edinburgh Council Leader and Chief Executive Edinburgh is the fastest growing city in the UK, with population growth of 1% per The vision for the city will require a well developed, integrated transport annum. By 2042, with some 750,000 residents, this increasing population will help network. There is, therefore, a compelling case for the development of this generate prosperity but is also living longer. With this in mind we need to take a strategy to support our priorities; Improve Quality of Life, Ensure Economic long-term view of the city. Our City Vision will be just that - a City Vision not a Vitality and to Build Excellent Places. The City Vision and City Deal will inform Council vision. The vision will be the output of a conversation with the whole city future iterations of this strategy. that will describe what the City of Edinburgh will look and feel like, for us all, in 2050. This strategy recognises the challenging landscape for transport in the Edinburgh City Region and beyond, with many stakeholders and actors. The developing City Vision and the Edinburgh and South East Scotland City Region We believe that there is a need to coordinate, collaborate and lead the Deal (City Deal) will inform the work of City of Edinburgh Council (CEC) and development of transport in Edinburgh. There is evidence from across the Transport for Edinburgh (TfE). Wherever the City Vision leads us, opportunities world that a well defined transport strategy, with stable governance, is like the City Deal will also offer us the chance to make decisions which will conducive to better transport.