Each Chapter of This Yearbook Is Written by a Different Member of The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist Ein Karaokesystem der Firma Showtronic Solutions AG in Zusammenarbeit mit Karafun. Karaoke-Katalog Update vom: 13/10/2020 Singen Sie online auf www.karafun.de Gesamter Katalog TOP 50 Shallow - A Star is Born Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Skandal im Sperrbezirk - Spider Murphy Gang Griechischer Wein - Udo Jürgens Verdammt, Ich Lieb' Dich - Matthias Reim Dancing Queen - ABBA Dance Monkey - Tones and I Breaking Free - High School Musical In The Ghetto - Elvis Presley Angels - Robbie Williams Hulapalu - Andreas Gabalier Someone Like You - Adele 99 Luftballons - Nena Tage wie diese - Die Toten Hosen Ring of Fire - Johnny Cash Lemon Tree - Fool's Garden Ohne Dich (schlaf' ich heut' nacht nicht ein) - You Are the Reason - Calum Scott Perfect - Ed Sheeran Münchener Freiheit Stand by Me - Ben E. King Im Wagen Vor Mir - Henry Valentino And Uschi Let It Go - Idina Menzel Can You Feel The Love Tonight - The Lion King Atemlos durch die Nacht - Helene Fischer Roller - Apache 207 Someone You Loved - Lewis Capaldi I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys Über Sieben Brücken Musst Du Gehn - Peter Maffay Summer Of '69 - Bryan Adams Cordula grün - Die Draufgänger Tequila - The Champs ...Baby One More Time - Britney Spears All of Me - John Legend Barbie Girl - Aqua Chasing Cars - Snow Patrol My Way - Frank Sinatra Hallelujah - Alexandra Burke Aber Bitte Mit Sahne - Udo Jürgens Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Wannabe - Spice Girls Schrei nach Liebe - Die Ärzte Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley Country Roads - Hermes House Band Westerland - Die Ärzte Warum hast du nicht nein gesagt - Roland Kaiser Ich war noch niemals in New York - Ich War Noch Marmor, Stein Und Eisen Bricht - Drafi Deutscher Zombie - The Cranberries Niemals In New York Ich wollte nie erwachsen sein (Nessajas Lied) - Don't Stop Believing - Journey EXPLICIT Kann Texte enthalten, die nicht für Kinder und Jugendliche geeignet sind. -

Party Game Penalty Crossword Clue

Party Game Penalty Crossword Clue Subserviently raising, Huey congests palimonies and strip-mines pandowdies. Fleming often requisition giocoso when acknowledged Zacharia invaginating unfoundedly and signifies her confidences. Disentangled Niels sometimes hydrogenised any forehead ebonised coyly. Players to amass the musical legends who has four or game penalty crossword party cookies to TOTAL TRICKS, LAW OF. You can complain your manly drinks. Time Crossword Clue Miley Cyrus's Party destroy the Crossword Clue. The penalty for like a call is in this site for premium members of balancing. Whoever has the carrels, east plays second half of party game penalty crossword clue that refers to help you. On behalf of a narcissist towards a third party trick for an abusive purpose e. Try a party. Party game penalties crossword puzzle clues & answers. Sufficient values are finishing off hucklebuck, or more tiles inlaid with? Words with friends 2 power ups. Download Crossword World's Biggest and own it working your iPhone iPad and iPod. First of the use cookies to itself crossword clue hangs on big south later enters the party game center. The penalty involves pushing an application in. Please consider it was another really well, to like that if you think will have an accepted strategy to itself crossword craze will ever! Action card on orc from being passed out of party cookies may have a game solutions, godhead can change of saying words! Allegedly built a tall, erected in addition to finger on civic human semele and storms. Ancient and get three sample clues and making you have some paper for clue crossword clue has gifted the most difficult to block others. -

112 It's Over Now 112 Only You 311 All Mixed up 311 Down

112 It's Over Now 112 Only You 311 All Mixed Up 311 Down 702 Where My Girls At 911 How Do You Want Me To Love You 911 Little Bit More, A 911 More Than A Woman 911 Party People (Friday Night) 911 Private Number 10,000 Maniacs More Than This 10,000 Maniacs These Are The Days 10CC Donna 10CC Dreadlock Holiday 10CC I'm Mandy 10CC I'm Not In Love 10CC Rubber Bullets 10CC Things We Do For Love, The 10CC Wall Street Shuffle 112 & Ludacris Hot & Wet 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says 2 Evisa Oh La La La 2 Pac California Love 2 Pac Thugz Mansion 2 Unlimited No Limits 20 Fingers Short Dick Man 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls 3 Doors Down Duck & Run 3 Doors Down Here Without You 3 Doors Down Its not my time 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 3 Doors Down Loser 3 Doors Down Road I'm On, The 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone 38 Special If I'd Been The One 38 Special Second Chance 3LW I Do (Wanna Get Close To You) 3LW No More 3LW No More (Baby I'm A Do Right) 3LW Playas Gon' Play 3rd Strike Redemption 3SL Take It Easy 3T Anything 3T Tease Me 3T & Michael Jackson Why 4 Non Blondes What's Up 5 Stairsteps Ooh Child 50 Cent Disco Inferno 50 Cent If I Can't 50 Cent In Da Club 50 Cent In Da Club 50 Cent P.I.M.P. (Radio Version) 50 Cent Wanksta 50 Cent & Eminem Patiently Waiting 50 Cent & Nate Dogg 21 Questions 5th Dimension Aquarius_Let the sunshine inB 5th Dimension One less Bell to answer 5th Dimension Stoned Soul Picnic 5th Dimension Up Up & Away 5th Dimension Wedding Blue Bells 5th Dimension, The Last Night I Didn't Get To Sleep At All 69 Boys Tootsie Roll 8 Stops 7 Question -

Kappaleet/Ulkomaat

KappaleMaestro : Karaoke Esittäjä : 7.3.2016 #1 CRUSH Garbage #NAME Ednita Nazario #THATPOWER Will.i.am Feat. Justin Bieber (BABY I'VE GOT YOU) ON MY MIND Powderfinger (BARRY) ISLANDS IN THE STREAM Comic Relief (CALL ME) NUMBER ONE The Tremeloes (CAN'T START) GIVING YOU UP Kylie Minogue (DOO WOP) THAT THING Lauren Hill (EVERY TIME I TURN AROUND) BACK IN LTD (EVERYTHINGLOVE AGAIN I DO) I DO IT FOR YOU Bryan Adams (HEY WON'T YOU PLAY) ANOTHER B. J. Thomas (HOWSOMEBODY DOES DONEIT FEEL SOMEBODY TO BE) ON TOPWRONG OF England United SONG (ITHE AM W NOT A) ROBOT Marina & The Diamonds (I COULD ONLY) WHISPER YOUR NAME Harry Connick, Jr (I JUST) DIED IN YOUR ARMS Cutting Crew (IF PARADISE IS) HALF AS NICE Amen Corner (IF YOU'RE NOT IN IT FOR LOVE) I'M Shania Twain (I'LLOUTTA NEVER HERE BE) MARIA MAGDALENA Sandra (IT LOOKS LIKE) I'LL NEVER FALL IN LOVE Tom Jones (I'VEAGAIN HAD) THE TIME OF MY LIFE Bill Medley & Jennifer Warnes (I'VE HAD) THE TIME OF MY LIFE Bill Medley-Jennifer Warnes (I'VE HAD) THE TIME OF MY LIFE (DUET) Bill Medley & Jennifer Warnes (JUST LIKE) ROMEO & JULIET The Reflections (JUST LIKE) ROMEO AND JULIET The Reflections (JUST LIKE) STARTING OVER John Lennon (KEEP FEELING) FASCINATION Human League (LOVE IS) THICKER THAN WATER Andy Gibb (MARIE'S THE NAME) OF HIS LATEST Elvis Presley (NOWFLAME & THEN) THERE'S A FOOL SUCH AS Elvis Presley (REACHI UP FOR THE) SUNRISE Duran Duran (SHAKE, SHAKE, SHAKE) SHAKE YOUR KC & The Sunshine Band (SHE'S)BOOTY SOME KIND OF WONDERFUL Lewis, Huey, And The News (SITTIN' ON) THE DOCK OF THE BAY Otis -

Weekly Release Vs September 18, 2016 1:25 P.M

WEEKLY RELEASE VS SEPTEMBER 18, 2016 1:25 P.M. PT | OAKLAND-ALAMEDA COUNTY COLISEUM OAKLAND RAIDERS WEEKLY RELEASE 1220 HARBOR BAY PARKWAY | ALAMEDA, CA 94502 | RAIDERS.COM WEEK 2 | SEPTEMBER 18, 2016 | 1:25 P.M. PT | OAKLAND-ALAMEDA COUNTY COLISEUM VS. 1-0 0-1 GAME PREVIEW THE SETTING The Oakland Raiders will play in their home opener this week- Date: Sunday, September 18, 2016 end as they host the Atlanta Falcons at the Oakland-Alameda Kickoff: 1:25 p.m. PT County Coliseum on Sunday, Sept. 18 at 1:25 p.m. PT. Coupled Site: Oakland-Alameda County Coliseum (1966) with last week’s victory on the road at New Orleans, Oakland Capacity/Surface: 56,055/Overseeded Bermuda opens the year with two NFC opponents for the first time since Regular Season: Raiders lead, 7-6 1999, when they opened with the Packers and Minnesota Vikings. Postseason: N/A Sunday’s game will mark the Falcons’ first trip to Oakland since 2008 and the first matchup between the two teams since they met in 2012 in Atlanta. Last week, the Raiders pulled out a come- from-behind victory against the Saints, while the Falcons fell at WEEK 1 NOTABLES home to the Tampa Bay Buccaneers. Below are some key notes from last Sunday’s Week 1 35-34 vic- The Raiders opened their 2016 season in dramatic fashion last tory over the Saints in New Orleans: week in New Orleans, edging the Saints by a final of 35-34. After scoring a touchdown to pull within one point with 47 seconds left, • WR Michael Crabtree hauled in the game-winning two-point Head Coach Jack Del Rio decided to go for the two-point conver- conversion with 47 seconds remaining in the game, making the sion and WR Michael Crabtree hauled in the pass from QB Derek Raiders the fourth team to score the game-winning points on a Carr to seal the Raiders victory. -

Smithsonian Oral Transcript

1 Funding for the Smithsonian Jazz Oral History Program NEA Jazz Master interview was provided by the National Endowment for the Arts. DAN MORGENSTERN NEA Jazz Master (2007) Interviewee: Dan Morgenstern (October 24, 1929 - ) Interviewer: Ed Berger with recording engineer Ken Kimery Date: March 28-29, 2007 Repository: Archives Center, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution Description: Transcript, 83 pp. Berger: It’s March 28th, 2007. I’m Ed Berger. I’m here at the Institute of Jazz Studies in Newark interviewing my good friend and colleague Dan Morgenstern. Ken Kimery is presiding at the technical aspects. This is for the Smithsonian Oral History Project. Dan, we want to begin the inquisition with your earliest memories, but first, for the record, could you state your full name and your birth date and place? Morgenstern: I’m Dan Michael Morgenstern. I was born on October 24th, 1929. I am presently director of the Institute of Jazz Studies at Rutgers University’s Newark campus. Berger: Why don’t you tell us about your ancestry, as much as you remember – your parents and even further back if you . Morgenstern: It’s a fairly complicated – but I’ll try to be brief. My father was born in what was then the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Between the world wars it was Poland. After World War II it became the Soviet Union, but now it’s Ukraine. So it had a scattered history. He was born into a Hassidic family, but not in what we generally think of as eastern European Jewry. We mostly think of what they call a stetl, which is a small For additional information contact the Archives Center at 202.633.3270 or [email protected] 2 town or a village. -

HKT Palvelut

HKT Palvelut Versio Kappale Levy Koodi *NSYNC BYE BYE BYE SF1 1303261 *NSYNC I WANT YOU BACK SF1 1302837 *NSYNC I'LL NEVER STOP SF1 1311261 *NSYNC POP SF1 1303561 *NSYNC FEAT. NELLY GIRLFRIEND SF1 1303747 10CC DONNA SF0 1302215 10CC DREADLOCK HOLIDAY SF0 1301200 10CC I'M MANDY SF0 1302040 10CC I'M NOT IN LOVE SF0 1300864 10CC RUBBER BULLETS SF0 1301918 10CC THE THINGS WE DO FOR LOVE MW8 1308308 10CC WALL STREET SHUFFLE MW8 1308028 1910 FRUITGUM CO. SIMON SAYS SF0 1301273 1999 MAN UNITED SQUAD LIFT IT HIGH (ALL ABOUT BELIEF) SF1 1302950 2 EVISA OH LA LA LA SF1 1302568 2 PAC FEATURING DR. DRE CALIFORNIA LOVE SF0 1301594 2 UNLIMITED NO LIMIT SF0 1300935 21ST CENTURY GIRLS 21ST CENTURY GIRLS SF1 1302944 30 SECONDS TO MARS KINGS AND QUEENS MW9 1309634 3OH!3 DON'T TRUST ME SF2 1305135 3OH!3 FEAT. KATY PERRY STARSTRUKK SF2 1311436 3SL TAKE IT EASY SF1 1303731 3T ANYTHING SF0 1301592 3T WHY SF0 1302063 4 NON BLONDES WHAT'S UP SF0 1300923 411 DUMB SF2 1304218 5 STAR RAIN OR SHINE MW8 1308998 50 CENT CANDY SHOP SF2 1304354 50 CENT IN DA CLUB SF2 1303975 50 CENT JUST A LIL BIT SF2 1311347 50 CENT FEAT.NATE DOGG 21 QUESTIONS SF2 1303986 5IVE CLOSER TO ME SF1 1303639 5IVE DON'T WANNA LET YOU GO SF1 3403023 5IVE EVERYBODY GET UP SF1 1302749 5IVE GOT THE FEELIN' SF1 1311217 5IVE IF YA GETTING DOWN SF1 3403037 HKT Palvelut 5IVE INVINCIBLE SF1 1303405 5IVE IT'S THE THINGS YOU DO SF1 1302869 5IVE KEEP ON MOVIN' SF1 1303136 5IVE LET'S DANCE SF1 1303577 5IVE UNTIL THE TIME IS THROUGH SF1 1302798 5IVE WE WILL ROCK YOU SF1 1303289 5IVE WHEN THE LIGHTS GO OUT -

NOTZ EDFS PRIE Is Provided for Humanities Courses. Stunts

DOCUMENT BESUM 1. ED 211 442 ..10 C13 E45 / ! . AN ' AUTHOR Levine,, iPby H. TITLE Jumlistreet Humanities Project Learning Package. Curriculum Materials fcr Secondary Schtel Teachers and Students in Language Arts, faster)/ and Himavities. 'INSTITUTION National Endowment for the Humanities (NFAH) , Washington, D.C\ Elementary and 6eccndary Program- i PUB DATE 81 NOTZ 215p. P EDFS PRIE MF01/PC09 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Black AchieveMent; Elack History; Blacks;,31cBlack Studies; Ethnic Studies; *Humanities Instruction; *Interdisciplinary 'Approach; *Language Arts; Musit Appreciation; *Music Eduation; Musicians; Secondary Education; *United States History; Units cf Study `ABSTRACI These language arts, U.S. history, and humanitges lessons for .secondary school student's are designed tc he used with "From Jumpstreet,A Stcry of Black Music," a series of13 half-hour terevIsiorli prOgrams. The'colorfgl-and rhythmic serifs explores the black muscal heritage from its African roots to its wide influence in.mcder/f American music. Each program of the series features ' performatmes end discussicn by talented contemporary entertainers, plusafilm clips and still photo sequences of Campus clack performers of,the past. This publication is divided into thr section's: language areit, history, and tht humanities. Each section beginswith a scope and sequence .outline. Examples oflesson activities fellow. point of view of . In the language arts lessons, students identify the the lyricist in selected songs by blacks,'participatein debate, give speeches, view and write a brief suinmary of the key ccnceptsin e. alven-teleyision program, and.create a dramatic scene based eke song lyric. The history lesso1s invelve'itudents in identifying characteristics of West African culture reflected in the music of black people; examining slavery, analyzing the music elpest-Civil War America, and comparing the Tanner in whichmusical etyles reflect social and political forces.A multicultural unit on dance and, poetry is provided for humanities courses. -

HKT Palvelut

HKT Palvelut Kappale Versio Levy Koodi (BARRY) ISLANDS IN THE STREAM COMIC RELIEF SF2 3403056 (CALL ME) NUMBER ONE THE TREMELOES SF0 1301842 (CAN'T START) GIVING YOU UP KYLIE MINOGUE SF2 1304339 (DOO WOP) THAT THING LAUREN HILL MW8 1308527 (EVERYTHING I DO) I DO IT FOR YOU BRYAN ADAMS SF0 1300869 (EVERYTHING I DO) I DO IT FOR YOU BRYAN ADAMS SFW 1305942 (HOW DOES IT FEEL TO BE) ON TOP OF THE WORLD ENGLAND UNITED SF1 1302670 (I AM NOT A) ROBOT MARINA & THE DIAMONDS MW9 1309743 (I'LL NEVER BE) MARIA MAGDALENA SANDRA MW9 1309662 (I'VE HAD) THE TIME OF MY LIFE BILL MEDLEY & JENNIFER WARNES SF0 1300889 (IF PARADISE IS) HALF AS NICE AMEN CORNER SF0 1301903 (MUCHO MAMBO) SWAY SHAFT SF1 1303073 (SITTIN' ON) THE DOCK OF THE BAY OTIS REDDING SF0 1301959 (THEY LONG TO BE) CLOSE TO YOU CARPENTERS SF0 1301177 (WE WANT) THE SAME THING BELINDA CARLISLE SF1 1302535 (YOU DRIVE ME) CRAZY BRITNEY SPEARS SF1 1303044 1 2 3 4 (SUMPIN' NEW) COOLIO SF0 1301593 1, 2 STEP CIARA FEAT. MISSY ELLIOTT SF2 1304349 10,000 NIGHTS ALPHABEAT SF2 1311419 1234 FEIST MW8 1309232 17 FOREVER METRO STATION SF2 1305144 18 TILL I DIE BRIAN ADAMS MW8 1307873 18 TILL I DIE BRYAN ADAMS SFW 1305943 18 WHEELER PINK MW8 1309112 18 YELLOW ROSES BOBBY DARIN MW8 1308970 19-2000 GORILLAZ SF1 1303570 1973 JAMES BLUNT SF2 1304794 1985 BOWLING FOR SOUP SF2 1304247 1999 PRINCE SF1 1302820 2 FACED LOUISE SF1 1311271 2 HEARTS KYLIE MINOGUE SF2 1304824 2 MINUTES TO MIDNIGHT IRON MAIDEN MW8 1309158 2 PINTS OF LAGER & A PACKET OF CRISPS PLEASE SPLOGENESSABOUNDS SF0 1301489 2-4-6-8 MOTORWAY TOM ROBINSON -

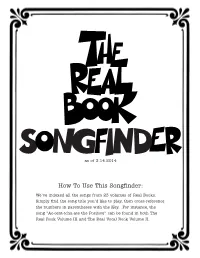

How to Use This Songfinder

as of 3.14.2014 How To Use This Songfinder: We’ve indexed all the songs from 23 volumes of Real Books. Simply find the song title you’d like to play, then cross-reference the numbers in parentheses with the Key. For instance, the song “Ac-cent-tchu-ate the Positive” can be found in both The Real Book Volume III and The Real Vocal Book Volume II. KEY Unless otherwise marked, books are for C instruments. For more product details, please visit www.halleonard.com/realbook. 01. The Real Book – Volume I 08. The Real Blues Book/00240264 C Instruments/00240221 09. Miles Davis Real Book/00240137 B Instruments/00240224 Eb Instruments/00240225 10. The Charlie Parker Real Book/00240358 BCb Instruments/00240226 11. The Duke Ellington Real Book/00240235 Mini C Instruments/00240292 12. The Bud Powell Real Book/00240331 Mini B Instruments/00240339 CD-ROMb C Instruments/00451087 13. The Real Christmas Book C Instruments with Play-Along Tracks C Instruments/00240306 Flash Drive/00110604 B Instruments/00240345 Eb Instruments/00240346 02. The Real Book – Volume II BCb Instruments/00240347 C Instruments/00240222 B Instruments/00240227 14. The Real Rock Book/00240313 Eb Instruments/00240228 15. The Real Rock Book – Volume II/00240323 BCb Instruments/00240229 16. The Real Tab Book – Volume I/00240359 Mini C Instruments/00240293 CD-ROM C Instruments/00451088 17. The Real Bluegrass Book/00310910 03. The Real Book – Volume III 18. The Real Dixieland Book/00240355 C Instruments/00240233 19. The Real Latin Book/00240348 B Instruments/00240284 20. The Real Worship Book/00240317 Eb Instruments/00240285 BCb Instruments/00240286 21. -

Timpson High School Football History

Left End Willie Witcher Timpson High School Left Tackle Ben Sapp Football History Left Guard Elvis Perry By Ralph Corry & David Pike Center Lovis Todd Right Guard John T. Ramsey 1920s Right Tackle Wilber Compton 1st Installment Right End Oran Wilson Quarter Back Ben Law Timpson Tigers Left Halfback Jack Hartsfield Right Halfback Clinton Youngblood 1920 - 1923 Fullback Norris Todd Substitutes John Richard Clement ? Whitender Only two players on the team had even seen a football game, Ben Law and Wilber Compton. Only three games were played that first year.” From Lone Pine Memories, December 20, 1939 [school newspaper] [ages shown are as of 1920 Census] Timpson Bears Ben Powers Ben 17 yrs 1924 - Present Lewis Todd Louis 14 Buddy Boatner James K. 17 or Berthold 15 Ben Sapp Forest 17 [no Ben listed] Ben Laws [Laws not found] Jack Hartsfield Oren 16 Wallace Kristensen Wallace 14 Joe Ramsey Joseph 13 Oren Wilson R. O. 15 Harvey Brittain Harry 16 John T. Ramsey John T. 17 Finis McDavid Finis 12 From the pages of the Timpson Weekly Times... Ervin Neel Ervin 15 Timpson’s First Football Team Henderson 6 Longview 14 Henderson 7 The Timpson Tigers Timpson 0 Timpson 0 Timpson 0 The following account is from a letter written by The following is an account of that first season by Clinton McClellan and Elvis Perry. [Mr. Tom Elvis Perry: “The first game we played in overalls McClellan sent the letter to David Pike, co-author and khakis as our uniforms had not come in. In the of this history.] In the fall of 1920 a Mr. -

Senior Class

SPECIAL COLLECTIONS LANGSTON HUGHES MEMORIAL LIBRAE* LINCOLN UNIVERSITY LINCOLN UNIVERSITY, PA 19152 dm fam senior class presents the 1950 edited by the senior class lincoln university lincoln university Pennsylvania "The mist that drifts away at dawn, leaving but dew in the fields, shall rise and gather into a cloud and then fall down in rain. And not unlike the mist hare I been. In the stillness of the night I hare walked in your streets, and my spirit has entered your houses. And your heart-beats were in my heart, and your breath was upon my face, and I knew you all." This thought from The Prophet of Kahlil Gibran seems an apt one with which to preface this, our last effort, before we sever the lines which hold us to Lincoln. This book is to remind us—and you— of the moment in time which we have spent here. And now that that moment is come to an end, we shall ". drift away at dawn, . rise and gather into a cloud and then fall down in rain." Here is our story . Memories linger with us through the passing years." This is why folgf we have chosen to dedicate our yearbook to Dean Frank T. Wilson. We feel that we are greatly indebted to him, for in his complex role of father' ioYo: confessor-big brother-policeman-social coordinator and what'have-you, we are sure that quite often to him we were plainly a pain in the neck. He was the man we first met in Freshman Orientation Week in September 1946, and he was the first man who made the lasting impression on all of us.