Paths to Perception a Search for Meaning in M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dragon and the Phoenix Teacher's Notes.Indd

Usborne English The Dragon and the Phoenix • Teacher’s notes Author: traditi onal, retold by Lesley Sims Reader level: Elementary Word count: 235 Lexile level: 350L Text type: Folk tale from China About the story A dragon and a phoenix live on opposite sides of a magic river. One day they meet on an island and discover a shiny pebble. The dragon washes it and the phoenix polishes it unti l it becomes a pearl. Its brilliant light att racts the att enti on of the Queen of Heaven, and that night she sends a guard to steal it while the dragon and phoenix are sleeping. The next morning, the dragon and phoenix search everywhere and eventually see their pearl shining in the sky. They fl y up to retrieve it, but the pearl falls down and becomes a lake on the ground below. The dragon and the phoenix lie down beside the lake, and are sti ll there today in the guise of Dragon Mountain and Phoenix Mountain. The story is based on The Bright Pearl, a Chinese folk tale. Chinese dragons are typically depicted without wings (although they are able to fl y), and are associated with water and wisdom. Chinese phoenixes are immortal, and do not need to die and then be reborn. They are associated with loyalty and honesty. The dragon and phoenix are oft en linked to the male yin and female yang qualiti es, and in the past, a Chinese emperor’s robes would typically be embroidered with dragons and an empress’s with phoenixes. -

Curiosity Killed the Bird: Arbitrary Hunting of Harpy Eagles Harpia

Cotinga30-080617:Cotinga 6/17/2008 8:11 AM Page 12 Cotinga 30 Curiosity killed the bird: arbitrary hunting of Harpy Eagles Harpia harpyja on an agricultural frontier in southern Brazilian Amazonia Cristiano Trapé Trinca, Stephen F. Ferrari and Alexander C. Lees Received 11 December 2006; final revision accepted 4 October 2007 Cotinga 30 (2008): 12–15 Durante pesquisas ecológicas na fronteira agrícola do norte do Mato Grosso, foram registrados vários casos de abate de harpias Harpia harpyja por caçadores locais, motivados por simples curiosidade ou sua intolerância ao suposto perigo para suas criações domésticas. A caça arbitrária de harpias não parece ser muito freqüente, mas pode ter um impacto relativamente grande sobre as populações locais, considerando sua baixa densidade, e também para o ecossistema, por causa do papel ecológico da espécie, como um predador de topo. Entre as possíveis estratégias mitigadoras, sugere-se utilizar a harpia como espécie bandeira para o desenvolvimento de programas de conservação na região. With adult female body weights of up to 10 kg, The study was conducted in the municipalities Harpy Eagles Harpia harpyja (Fig. 1) are the New of Alta Floresta (09º53’S 56º28’W) and Nova World’s largest raptors, and occur in tropical forests Bandeirantes (09º11’S 61º57’W), in northern Mato from Middle America to northern Argentina4,14,17,22. Grosso, Brazil. Both are typical Amazonian They are relatively sensitive to anthropogenic frontier towns, characterised by immigration from disturbance and are among the first species to southern and eastern Brazil, and ongoing disappear from areas colonised by humans. fragmentation of the original forest cover. -

California Folklore Miscellany Index

Topics: A - Mass Vol Page Topics: Mast - Z Vol Page Abbreviations 19 264 Mast, Blanche & Family 36 127-29 Abernathy 16 13 Mathematics 24 62 Abominable Snowman in the Trinity 26 262-3 Mattole 4 295 Alps Abortion 1 261 Mauk, Frank 34 89 Abortion 22 143 Mauldin, Henry 23 378-89 Abscess 1 226 Maxwell, Mrs. Vest Peak 9 343 Absent-Minded Professor 35 109 May Day 21 56 Absher Family History 38 152-59 May Day (Kentfield) 7 56 AC Spark Plug 16 44 Mayor of White's Hill 10 67 Accidents 20 38 Maze, The Mystic 17 210-16 Accidents 24 61, 74 McCool,Finn 23 256 Ace of Spades 5 347-348 McCoy, Bob (Wyoming character) 27 93 Acorn Acres Ranch 5 347-348 McCoy, Capt. Bill 23 123 Acorn dance 36 286 McDonal House Ghost 37 108-11 Acorn mush 4 189 McGettigan, Louis 9 346 Acorn, Black 24 32 McGuire, J. I. 9 349 Acorns 17 39 McKiernan,Charles 23 276-8 Actress 20 198-9 McKinley 22 32 Adair, Bethena Owens 34 143 McKinleyville 2 82 Adobe 22 230 McLean, Dan 9 190 Adobe 23 236 McLean, Dan 9 190 Adobe 24 147 McNear's Point 8 8 Adobe house 17 265, 314 McNeil, Dan 3 336 Adobe Hut, Old 19 116, 120 Meade, Ed (Actor) 34 154 Adobe, Petaluma 11 176-178 Meals 17 266 Adventure of Tom Wood 9 323 Measles 1 238 Afghan 1 288 Measles 20 28 Agriculture 20 20 Meat smoking, storing 28 96 Agriculture (Loleta) 10 135 Meat, Salting and Smoking 15 76 Agwiworld---WWII, Richfield Tank 38 4 Meats 1 161 Aimee McPherson Poe 29 217 Medcalf, Donald 28 203-07 Ainu 16 139 Medical Myths 15 68 Airline folklore 29 219-50 Medical Students 21 302 Airline Lore 34 190-203 Medicinal plants 24 182 Airplane -

Research Article WILDMEN in MYANMAR

The RELICT HOMINOID INQUIRY 4:53-66 (2015) Research Article WILDMEN IN MYANMAR: A COMPENDIUM OF PUBLISHED ACCOUNTS AND REVIEW OF THE EVIDENCE Steven G. Platt1, Thomas R. Rainwater2* 1 Wildlife Conservation Society-Myanmar Program, Office Block C-1, Aye Yeik Mon 1st Street, Hlaing Township, Yangon, Myanmar 2 Baruch Institute of Coastal Ecology and Forest Science, Clemson University, P.O. Box 596, Georgetown, SC 29442, USA ABSTRACT. In contrast to other countries in Asia, little is known concerning the possible occurrence of undescribed Hominoidea (i.e., wildmen) in Myanmar (Burma). We here present six accounts from Myanmar describing wildmen or their sign published between 1910 and 1972; three of these reports antedate popularization of wildmen (e.g., yeti and sasquatch) in the global media. Most reports emanate from mountainous regions of northern Myanmar (primarily Kachin State) where wildmen appear to inhabit montane forests. Wildman tracks are described as superficially similar to human (Homo sapiens) footprints, and about the same size to almost twice the size of human tracks. Presumptive pressure ridges were described in one set of wildman tracks. Accounts suggest wildmen are bipedal, 120-245 cm in height, and covered in longish pale to orange-red hair with a head-neck ruff. Wildmen are said to utter distinctive vocalizations, emit strong odors, and sometimes behave aggressively towards humans. Published accounts of wildmen in Myanmar are largely based on narratives provided by indigenous informants. We found nothing to indicate informants were attempting to beguile investigators, and consider it unlikely that wildmen might be confused with other large mammals native to the region. -

Dragons and Serpents in JK Rowling's <I>Harry Potter</I> Series

Volume 27 Number 1 Article 6 10-15-2008 Dragons and Serpents in J.K. Rowling's Harry Potter Series: Are They Evil? Lauren Berman University of Haifa, Israel Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons Recommended Citation Berman, Lauren (2008) "Dragons and Serpents in J.K. Rowling's Harry Potter Series: Are They Evil?," Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature: Vol. 27 : No. 1 , Article 6. Available at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/vol27/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Mythopoeic Society at SWOSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature by an authorized editor of SWOSU Digital Commons. An ADA compliant document is available upon request. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To join the Mythopoeic Society go to: http://www.mythsoc.org/join.htm Mythcon 51: A VIRTUAL “HALFLING” MYTHCON July 31 - August 1, 2021 (Saturday and Sunday) http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-51.htm Mythcon 52: The Mythic, the Fantastic, and the Alien Albuquerque, New Mexico; July 29 - August 1, 2022 http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-52.htm Abstract Investigates the role and symbolism of dragons and serpents in J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter series, with side excursions into Lewis and Tolkien for their takes on the topic. Concludes that dragons are morally neutral in her world, while serpents generally represent or are allied with evil. -

Feral Swine Disease Control in China

2014 International Workshop on Feral Swine Disease and Risk Management By Hongxuan He Feral swine diseases prevention and control in China HONGXUAN HE, PH D PROFESSOR OF INSTITUTE OF ZOOLOGY, CHINESE ACADEMY OF SCIENCES EXECUTIVE DEPUTY DIRECTOR OF NATIONAL RESEARCH CENTER FOR WILDLIFE DISEASES COORDINATOR OF ASIA PACIFIC NETWORK OF WILDLIFE BORNE DISEASES CONTENTS · Feral swine in China · Diseases of feral swine · Prevention and control strategies · Influenza in China Feral swine in China 4 Scientific Classification Scientific name: Sus scrofa Linnaeus Common name: Wild boar, wild hog, feral swine, feral pig, feral hog, Old World swine, razorback, Eurasian wild boar, Russian wild boar Feral swine is one of the most widespread group of mammals, which can be found on every continent expect Antarctica. World distribution of feral swine Reconstructed range of feral swine (green) and introduced populations (blue). Not shown are smaller introduced populations in the Caribbean, New Zealand, sub-Saharan Africa and elsewhere. Species of feral swine Now ,there are 4 genera and 16 species recorded in the world today. Western Indian Eastern Indonesian genus genus genus genus Sus scrofa scrofa Sus scrofa Sus scrofa Sus scrofa Sus scrofa davidi sibiricus vittatus meridionalis Sus scrofa Sus scrofa Sus scrofa algira cristatus ussuricus Sus scrofa Attila Sus scrofa Sus scrofa leucomystax nigripes Sus scrofa Sus scrofa riukiuanus libycus Sus scrofa Sus scrofa majori taivanus Sus scrofa moupinensis Feral swine in China Feral swine has a long history in China. About 10,000 years ago, Chinese began to domesticate feral swine. Feral swine in China Domesticated history in China oracle bone inscriptions of “猪” in Different font of “猪” Shang Dynasty Feral swine in China Domesticated history in China The carving of pig in Han Dynasty Feral swine in China Domesticated history in China In ancient time, people domesticated pig in “Zhu juan”. -

Siren Motifs on Glazed Dishes

Art This is how the harpies and sirens were seen in Europe in the Middle Ages 34 www.irs-az.com 2(30), SPRING 2017 Aida ISMAYILOVA Siren motifs on glazed dishes (Based on materials of the National Azerbaijan History Museum) www.irs-az.com 35 Art This is how the harpies and sirens were seen in ancient Greece. Image on a ceramic vase he National Azerbaijan History Museum (NAHM) is mation about the semantics of the image with a human rich in archaeological materials belonging to vari- head and a bird’s body. Tous periods of our history, including the 12th-13th First of all, let’s get acquainted with the description centuries. Based on this material evidence, we can study of the material cultural artifacts we mentioned above: the artistic and aesthetic image and world outlook of A fragment of a dish was found in the urban area of the period, as well as its principle of cultural succession. Beylagan in 1963 (1, No 25058). The clay of the glazed From this point of view, we will be talking about archaeo- fragment was bright orange and well fired. The inter- logical materials, which belong to the aforesaid period, nal surface is covered with engobing and is glazed with found in the urban areas of Beylagan and Bandovan and images of birds and plants engraved on it. The outlines handed over to the NAHM from the Nizami museum. of the image are bright brown. The profile of a bird is The particularity of these material cultural artifacts is that depicted from the right side. -

Phoenix Helps Fintech Unicorn Pine Labs Again on $285M Fundraise with NDA, AZB, Khaitan, Gledhill, Simmons, Goodwin in Brief

Subscribe for perks & to support LI LI TOPICAL CORPORATE LEAGUE TABLES STUDENTS BAR CONTACT 2019 INLEGAL 50 Sundarbans, West Bengal The IDIA Charitable Trust: Setting up isolation centres and arranging medical support. IDIA is organising a pilot project in rural areas of West Bengal (Sundarbans), and are setting up isolation centres, boat ambulances, conducting medical tests, oximeter checks, establishing verified information portals, blood donation camps etc for that area. Support rural India and NGOs such as this one with emergency help via NGOs vetted by the COVID Rural Response Tracker project. Phoenix helps fintech unicorn Pine Labs again on $285m fundraise with NDA, AZB, Khaitan, Gledhill, Simmons, Goodwin In Brief Pine Labs, the digital payments and commerce solutions provider to merchants, said it has raised $285 million in new funding from public market crossover investors, including Marshall Wace, Baron Capital Group, Duro Capital, Moore Strategic Ventures and Ward Ferry Management. Its existing investors—Temasek, Lone Pine Capital and Sunley House Capital have also participated in this funding round. Economic Times With the fundraise, Pine Labs’ valuation rose up to USD 3 billion. The POS device and merchant commerce platform plans to use the fresh funds to scale its merchant network both in the online space as well as continue to power the credit and commerce needs of their offline merchant partners. Phoenix Legal advised Pine Labs (again, probably making it one of the firm’s marquee start-up clients) led by a team of partners Saket Shukla and Sriram Ramachandran along with associates Maryam Naaz Quadri and Ishani Chopra. Pine Labs in-house GC Shalini Saxena also assisted in the deal. -

Phoenix Trail Guide

WELCOME SAFETY TIPS SEASONS Mother Nature smiles on some cities more than others. Phoenix, Most of the mountain parks and preserves in Greater Phoenix are undeveloped Welcome to Greater Phoenix, America’s sunniest obviously, is blessed in the sunshine department. Sonoran Desert areas. Hikers may encounter rocky terrain, rattlesnakes, bees destination. and other hazards native to this ecosystem. These safety tips are crucial to Phoenix basks in sunshine more than any other major metropolitan area read before embarking on a hike in the desert. in the U.S. — during 85 percent of its daylight hours. And the cliché What sets Phoenix apart from every other big city in the that “it’s a dry heat” rings true: Humidity levels are pleasantly low, even United States is its Sonoran Desert scenery. Phoenix • Drink plenty of water. Bring at least 1 quart for short hikes, and in summer. is surrounded on all sides by mountains, and the sun 3-5 quarts for daylong hikes. When you’ve consumed half of your shines during 85 percent of daylight hours. water, turn around. The bottom line: Any time is a good time to visit the Sonoran Desert. • Make sure someone knows where you’ll be hiking and when you Phoenix has more acreage of parks and preserves than expect to return. WINTER • Hike with a friend. It’s safer … and more fun. any other major destination in the nation, and visitors @jacquelinehurst at Phoenix Mountain Preserve Trail #300 (Summit/Piestewa Peak) During the winter months Greater Phoenix enjoys blue skies and highs in • During hot-weather months, hike in the early morning or near dusk. -

The Harpy of 1784 and Meanings of Monstrosity in Eighteenth-Century France

W&M ScholarWorks Undergraduate Honors Theses Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 7-2011 "Heretofore Considered Legendary": The Harpy of 1784 and Meanings of Monstrosity in Eighteenth-Century France Philippe Langellier Bellevue Halbert College of William and Mary Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses Part of the French and Francophone Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Halbert, Philippe Langellier Bellevue, ""Heretofore Considered Legendary": The Harpy of 1784 and Meanings of Monstrosity in Eighteenth-Century France" (2011). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 439. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses/439 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “Heretofore Considered Legendary” The Harpy of 1784 and Meanings of Monstrosity in Eighteenth-Century France A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Bachelors of Arts in French from The College of William and Mary by Philippe Langellier Bellevue Halbert Accepted for ___________________________________ (Honors, High Honors, Highest Honors) ____________________________________ Giulia Pacini, Director ____________________________________ Gail Bossenga ____________________________________ Nicolas Médevielle Williamsburg, Virginia 28 April, -

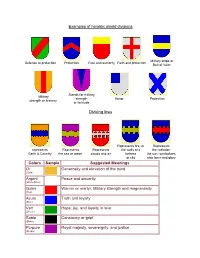

Examples of Heraldic Shield Divisions Dividing Lines Colors Sample

Examples of heraldic shield divisions Military strips or Defense or protection Protection Rule and authority Faith and protection Belt of Valor Stands for military Military strength Honor Protection strength or bravery. or fortitude. Dividing lines Represents fire, or Represents represents Represents Represents the walls of a the radiation Earth & Country the sea or water clouds and air fortress the sun. symbolizes or city also fame and glory Colors Sample Suggested Meanings Or Generosity and elevation of the mind (Gold) Argent Peace and sincerity (White/Silver) Gules Warrior or martyr; Military strength and magnanimity (Red) Azure Truth and loyalty (Blue) Vert Hope, joy, and loyalty in love (Green) Sable Constancy or grief (Black) Purpure Royal majesty, sovereignty, and justice (Purple) Tenne Worthy ambition (Orange) Sanguine Patient in battle, and yet victorious (Maroon) v Charges: Suggested Meanings: Acacia Branch Eternal and affectionate remembrance both for the living and the dead. Acorn Life, immortality and perseverence Anchor Christian emblem of hope and refuge; awarded to sea warriors for special feats performed Also signifies steadfastness and stability. In seafaring nations, the anchor is a symbol of good luck, of safety, and of security Annulet Emblem of fidelity; Also a mark of Cadency of the fifth son Antelope Represents action, agility and sacrifice and a very worthy guardian that is not easily provoked, but can be fierce when challenged Antlers Strength and fortitude Anvil Honour and strength; chief emblem of the smith's trade Arrow Readiness; if with a cross it denotes affliction; a bow and arrow signifies a man resolved to abide the uttermost hazard of battle. -

Christiansted National Historic Site AND/OR HISTORIC: Wharf Area, Christiansted

3- Form 10-306 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR (Oct. 1972) NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES St. Croix INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM FOR NPS USE ONLY FOR FEDERAL PROPERTIES ENTRY DATE (Type all entries - complete applicable sections) COMMON: Christiansted National Historic Site AND/OR HISTORIC: Wharf Area, Christiansted STREET AND NUMBER: Christiansted National Historic Site CITY OR TOWN: ___Christiansted. St. Croix STATE: CODE Virgin Islands 078 CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS ACCESSIBLE (Check One) TO THE PUBLIC District Q Building (31 Public Public Acquisition: Occupied Yes: Sit* Q Structure Q Private Q In Process f~1 Unoccupied O Restricted 0 Object Cl Both ( I Being Considered (~1 Preservation work 2] Unrestricted In progress QNo PRESENT USE (Check One or Man a* Appropriate; O Agricultural Government I I Transportation Q Comments [ | Commercial Industrial [~1 Private Residence Q Other (Spicily) C] Educational ilitary [~) Religious |~1 Entertainment X I Museum I I Scientific National Park Service REGIONAL HEADQUARTERS: (II applicable) STRBET AND NUMBER: Southeast Region 1895 Phoenix Boulevard CITY ON TOWN: STATE: COD* M Atlanta Georgia 30349 13 COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC: Registry of Deeds, Government House STREET AND NUMBER! King Street CITY OR TOWN: Christiansted, St. Croix Virgin Islands 078 TITLE OF SURVEY:: Fort Christiansvaern, Scale House, Steeple Building, Old Customs House, Histnrir American *--- - -- - *» DATE OF SURVEY, 1957-1Q61 QJ Federal County O Local DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS: