Locus B of RIV-11775 Two Views Inside of Feature 3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Results of the Cultural Resources Survey for the Monte Vista Regional Soccer and Wellness Park Project Imperial County, California

Results of the Cultural Resources Survey for the Monte Vista Regional Soccer and Wellness Park Project Imperial County, California Prepared for City of El Centro Community Development Department 1275 Main Street El Centro, CA 92243 Contact: Norma Villicaña Prepared by RECON Environmental, Inc. 3111 Camino del Rio North, Suite 600 San Diego, CA 92108-5726 P 619.308.9333 RECON Number 9781 November 6, 2020 Nathanial Yerka, Project Archaeologist Results of Cultural Resources Survey NATIONAL ARCHAEOLOGICAL DATA BASE INFORMATION Author: Nathanial Yerka Consulting Firm: RECON Environmental, Inc. 3111 Camino del Rio North, Suite 600 San Diego, CA 92108-5726 Report Date: November 6, 2020 Report Title: Results of the Cultural Resources Survey for the Monte Vista Regional Soccer and Wellness Park Project Imperial County, California Prepared for: City of El Centro Community Development Department 1275 Main Street El Centro, CA 92243 Contract Number: RECON Number 9781 USGS Quadrangle Map: El Centro, California, quadrangle, 1979 edition Acreage: 63 acres Keywords: Cultural resources survey, negative prehistoric resources, Date Drain, Dahlia Canal Lateral 1, Imperial Irrigation District, internal canal system This report summarizes the results of the cultural resources field and archival investigation for the Monte Vista Regional Soccer and Wellness Park Project, in the county of Imperial, California. The approximately 80-acre project area is located within the city of El Centro, situated south of West McCabe Road, west of Sperber Road, east and adjacent to a portion of the Dahlia Canal, and approximately 2.5 miles north of the Imperial Valley Irrigation Network’s Main Canal. The assessor’s parcel number for the site is 054-510-001. -

1 Ph.D., Geophysics, California Institute of Technology

ANDREA DONNELLAN, PH.D. Education Ph.D., Geophysics, California Institute of Technology (1991) M.S., Computer Science, University of Southern California (2003) M.S., Geophysics, California Institute of Technology (1988) B.S., Geology, Ohio State University, with honors and distinction in geology and minor in math (1986) Bio Andrea Donnellan has been employed in science research and related management positions since 1982. She thrives on building programs and developing new areas of research. Her work experience covers research, line, and program management. As Deputy Manager of the NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory’s Science Division, she oversaw 400+ scientists, postdocs, students, and administrative staff. Throughout her career, Donnellan has remained active in research both because of her scientific curiosity and because she feels that effective leadership requires insights into research methods and the challenges faced by researchers. Her experience leading NASA’s Applied Sciences Program for Natural Disasters connected her to a wide range of institutions and lines of research. Mission experience includes pre-project scientist of DESDynI, which is now the NISAR mission, participation on review boards, and as a current member of the NISAR project team. For nearly 20 years Donnellan has managed GeoGateway (http://geo-gateway.org), previously called QuakeSim, a multi-institutional research team developing computational infrastructure for remote sensing data and studying earthquake processes. QuakeSim was awarded NASA’s Software of the Year Award in 2012. Donnellan was instrumental in establishing the Southern California Integrated GPS Network, a $20M initiative to use 250 continuous GPS stations to study earthquakes funded by NASA, the NSF, USGS, and WM Keck Foundation. -

Greater Palm Springs Brochure

ENGLISH Find your oasis. SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA’S LOCATION OASIS Located just two hours east of Los Angeles, Greater Palm Springs is among Southern California’s most prized destinations. It boasts an incomparable collection of seductive luxury hotels, resorts and spas; world-class music and film festivals; and nine different cities each with their own neighborhood feel. Greater Palm Springs serves as the gateway to Joshua Tree National Park. palm springs international airport (PSP) air service Edmonton Calgary Vancouver Bellingham Seattle/ Winnipeg Tacoma Portland Toronto Minneapolis/ Boston St. Paul New York - JFK Newark Salt Lake City Chicago San Francisco ORD Denver Los Angeles PSP Atlanta Phoenix Dallas/Ft. Worth Houston airlines servicing greater palm springs: Air Canada Frontier Alaska Airlines JetBlue Allegiant Air Sun Country American Airlines United Airlines Delta Air Lines WestJet Routes and carriers are subject to change Flair PALM SPRINGS INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT (PSP) Named as one the “Top Ten Stress-Free U.S. Airports” by SmarterTravel.com, Palm Springs International Airport (PSP) welcomes visitors with a friendly, VIP vibe. Airport scores high marks with travelers for quick check-ins and friendly, fast TSA checkpoints, plus the added bonus that PSP is only minutes from plane to baggage to area hotels. AIR SERVICE PARTNERS FROM SAN FRANCISCOC A L I F O R N I A N E V A D A FO U Las Vegas R- HO Grand Canyon U NONSTOP FLIGHTS R FROM CANADA TO PSP D R IV E TH RE E- HO U R D R Flagstaff 5 IV E 15 TW O- HO U R D 40 R IV Santa Barbara -

Anza-Borrego Desert State Park Bibliography Compiled and Edited by Jim Dice

Steele/Burnand Anza-Borrego Desert Research Center University of California, Irvine UCI – NATURE and UC Natural Reserve System California State Parks – Colorado Desert District Anza-Borrego Desert State Park & Anza-Borrego Foundation Anza-Borrego Desert State Park Bibliography Compiled and Edited by Jim Dice (revised 1/31/2019) A gaggle of geneticists in Borrego Palm Canyon – 1975. (L-R, Dr. Theodosius Dobzhansky, Dr. Steve Bryant, Dr. Richard Lewontin, Dr. Steve Jones, Dr. TimEDITOR’S Prout. Photo NOTE by Dr. John Moore, courtesy of Steve Jones) Editor’s Note The publications cited in this volume specifically mention and/or discuss Anza-Borrego Desert State Park, locations and/or features known to occur within the present-day boundaries of Anza-Borrego Desert State Park, biological, geological, paleontological or anthropological specimens collected from localities within the present-day boundaries of Anza-Borrego Desert State Park, or events that have occurred within those same boundaries. This compendium is not now, nor will it ever be complete (barring, of course, the end of the Earth or the Park). Many, many people have helped to corral the references contained herein (see below). Any errors of omission and comission are the fault of the editor – who would be grateful to have such errors and omissions pointed out! [[email protected]] ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS As mentioned above, many many people have contributed to building this database of knowledge about Anza-Borrego Desert State Park. A quantum leap was taken somewhere in 2016-17 when Kevin Browne introduced me to Google Scholar – and we were off to the races. Elaine Tulving deserves a special mention for her assistance in dealing with formatting issues, keeping printers working, filing hard copies, ignoring occasional foul language – occasionally falling prey to it herself, and occasionally livening things up with an exclamation of “oh come on now, you just made that word up!” Bob Theriault assisted in many ways and now has a lifetime job, if he wants it, entering these references into Zotero. -

North American Deserts Chihuahuan - Great Basin Desert - Sonoran – Mojave

North American Deserts Chihuahuan - Great Basin Desert - Sonoran – Mojave http://www.desertusa.com/desert.html In most modern classifications, the deserts of the United States and northern Mexico are grouped into four distinct categories. These distinctions are made on the basis of floristic composition and distribution -- the species of plants growing in a particular desert region. Plant communities, in turn, are determined by the geologic history of a region, the soil and mineral conditions, the elevation and the patterns of precipitation. Three of these deserts -- the Chihuahuan, the Sonoran and the Mojave -- are called "hot deserts," because of their high temperatures during the long summer and because the evolutionary affinities of their plant life are largely with the subtropical plant communities to the south. The Great Basin Desert is called a "cold desert" because it is generally cooler and its dominant plant life is not subtropical in origin. Chihuahuan Desert: A small area of southeastern New Mexico and extreme western Texas, extending south into a vast area of Mexico. Great Basin Desert: The northern three-quarters of Nevada, western and southern Utah, to the southern third of Idaho and the southeastern corner of Oregon. According to some, it also includes small portions of western Colorado and southwestern Wyoming. Bordered on the south by the Mojave and Sonoran Deserts. Mojave Desert: A portion of southern Nevada, extreme southwestern Utah and of eastern California, north of the Sonoran Desert. Sonoran Desert: A relatively small region of extreme south-central California and most of the southern half of Arizona, east to almost the New Mexico line. -

Native American Settlement to 1969

29 Context: Native American Settlement to 1969 Francisco Patencio outside the roundhouse, c. 1940. Source: Palm Springs Historical Society. FINAL DRAFT – FOR CITY COUNCIL APPROVAL City of Palm Springs Citywide Historic Context Statement & Survey Findings HISTORIC RESOURCES GROUP 30 CONTEXT: NATIVE AMERICAN SETTLEMENT TO 196923 The earliest inhabitants of the Coachella Valley are the Native people known ethnohistorically as the Cahuilla Indians. The Cahuilla territory includes the areas from the San Jacinto Mountains, the San Gorgonia Pass, and the desert regions reaching east to the Colorado River. The Cahuilla language is part of the Takic branch of the Uto-Aztecan language family and all the Cahuilla groups speak a mutually intelligible despite different dialects. The Cahuilla group that inhabited the Palm Springs area are known as the Agua Caliente Band of Cahuilla Indians. The Cahuilla name for the area that is now Palm Springs is Sec-he, “boiling water,” named for the hot springs located in what is currently the center of the Palm Springs business district. The springs have always provided clean water, bathing, and a connection to the spiritual world, and were used for ceremonial and healing purposes.24 The Cahuilla people refer to themselves as ‘ivi’lyu’atum and are ethnographically divided into two patrilineal moieties: the Wildcats and the Coyotes. Each moiety was further divided into clans which are made up of lineages. Lineages had their own territory and hunting rights within a larger clan territory. There are a number of lineages in the Palm Springs area, which each have religious and political autonomy. Prior to European contact, Cahuilla communities established summer settlements in the palm-lined mountain canyons around the Coachella valley; oral histories and archaeological evidence indicates that they settled in the Tahquitz Canyon at least 5,000 years ago.25 The Cahuilla moved each winter to thatched shelters clustered around the natural mineral hot springs on the valley floor. -

Sonny Bono Salton Sea National Wildlife Refuge Complex

Appendix J Cultural Setting - Sonny Bono Salton Sea National Wildlife Refuge Complex Appendix J: Cultural Setting - Sonny Bono Salton Sea National Wildlife Refuge Complex The following sections describe the cultural setting in and around the two refuges that constitute the Sonny Bono Salton Sea National Wildlife Refuge Complex (NWRC) - Sonny Bono Salton Sea NWR and Coachella Valley NWR. The cultural resources associated with these Refuges may include archaeological and historic sites, buildings, structures, and/or objects. Both the Imperial Valley and the Coachella Valley contain rich archaeological records. Some portions of the Sonny Bono Salton Sea NWRC have previously been inventoried for cultural resources, while substantial additional areas have not yet been examined. Seventy-seven prehistoric and historic sites, features, or isolated finds have been documented on or within a 0.5- mile buffer of the Sonny Bono Salton Sea NWR and Coachella Valley NWR. Cultural History The outline of Colorado Desert culture history largely follows a summary by Jerry Schaefer (2006). It is founded on the pioneering work of Malcolm J. Rogers in many parts of the Colorado and Sonoran deserts (Rogers 1939, Rogers 1945, Rogers 1966). Since then, several overviews and syntheses have been prepared, with each succeeding effort drawing on the previous studies and adding new data and interpretations (Crabtree 1981, Schaefer 1994a, Schaefer and Laylander 2007, Wallace 1962, Warren 1984, Wilke 1976). The information presented here was compiled by ASM Affiliates in 2009 for the Service as part of Cultural Resources Review for the Sonny Bono Salton Sea NWRC. Four successive periods, each with distinctive cultural patterns, may be defined for the prehistoric Colorado Desert, extending back in time over a period of at least 12,000 years. -

TAHQUITZ CREEK TRAIL MASTER PLAN Background, Goals and Design Standards Tahquitz Creek Trail Master Plan

TAHQUITZ CREEK T RAIL MASTER PLAN PREPARED FOR: THE CITY OF PALM SPRINGS PARKS & RECREATION DEPARTMENT PREPARED BY: ALTA PLANNING + DESIGN WITH RBF CONSULTING MARCH 2010 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Deep appreciati on to the neighborhood groups and community members who conti nue to work ti relessly to bring the vision of the Tahquitz Creek Trail to fruiti on. Steering Committ ee Members Council Member Ginny Foat April Hildner Jim Lundin Bill Post Max Davila Lauri Aylaian Steve Sims Mike Hutchison Renee Cain Nanna D. A. Nanna Sharon Heider, Director City of Palm Springs Department of Parks and Recreati on 401 South Pavilion Way P.O. Box 2743 Palm Springs, CA 922-2743 George Hudson, Principal Karen Vitkay, Project Manager Alta Planning + Design, Inc. 711 SE Grand Avenue Portland, Oregon 97214 www.altaplanning.com RBF Consulti ng Brad Mielke, S.E., P.E. 74-130 Country Club Drive, Suite 201 Palm Desert, CA 92260-1655 www.RBF.com TABLE OF CONTENTS Background, Goals and Design and Standards .............................................1 Background ...................................................................................................... 2 Vision Statement .............................................................................................. 2 Goals and Objecti ves ........................................................................................ 3 Trail Design Standards .......................................................................................4 Multi -Use Trail Design ...................................................................................... -

An Early Human Fossil from the Yuha Desert of Southern California

REVIEWS 137 aroused." Echoes of these old hatreds indeed (Childers 1974; Bischoff et al. 1976). In the exist today in academic and legislative debate. present monograph the skeleton itself is analyzed. Rogers' report, as might be expected from his previous work, is detailed and fully pro fessional. Though hampered by the highly fragmented and eroded condition of the find A n Early Human Fossil from the Yuha Desert (the skull vault alone was crushed into some 90 of Southern California: Physical Char pieces), he establishes the sex as probably acteristics. Spencer L. Rogers. San Diego: male, age as late adolescence (17-20), stature as San Diego Museum of Man Papers "No. 12. less than 160 cm., and provides a series of 1977. 27 pp., map, figures, bibhography. osteometric and morphological observations. $3.00 (paper). Although the main contribution of the Reviewed by PETER D. SCHULZ work is a straightforward osteological study, the greatest interest wiU undoubtedly center on University of California. Davis the two short secfions enfitled "Racial Charac Debate over the antiquity of man in the teristics" and "Comparisons." Unfortunately, New World has been a recurrent theme in these are the weakest sections of the report. modern archaeology for much of this century, Although the Yuha find is assessed (on non- but only in recent years has the controversy metric features) as "a cranium with more tended to concentrate in southern California. Caucasoid than Mongoloid elements," the two Numerous finds of purported great antiquity terms are never defined—a serious omission in have now been recovered there. These are view of the variability in their use, even among distributed from the Channel Islands and the physical anthropologists, and particularly in San Diego Coast to the Colorado and Mojave view of the discussions of "proto-Caucasoid" deserts, with estimated ages ranging from affiliations which have been popular of late 16,000 to more than 100,000 years. -

The California Desert CONSERVATION AREA PLAN 1980 As Amended

the California Desert CONSERVATION AREA PLAN 1980 as amended U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR BUREAU OF LAND MANAGEMENT U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Land Management Desert District Riverside, California the California Desert CONSERVATION AREA PLAN 1980 as Amended IN REPLY REFER TO United States Department of the Interior BUREAU OF LAND MANAGEMENT STATE OFFICE Federal Office Building 2800 Cottage Way Sacramento, California 95825 Dear Reader: Thank you.You and many other interested citizens like you have made this California Desert Conservation Area Plan. It was conceived of your interests and concerns, born into law through your elected representatives, molded by your direct personal involvement, matured and refined through public conflict, interaction, and compromise, and completed as a result of your review, comment and advice. It is a good plan. You have reason to be proud. Perhaps, as individuals, we may say, “This is not exactly the plan I would like,” but together we can say, “This is a plan we can agree on, it is fair, and it is possible.” This is the most important part of all, because this Plan is only a beginning. A plan is a piece of paper-what counts is what happens on the ground. The California Desert Plan encompasses a tremendous area and many different resources and uses. The decisions in the Plan are major and important, but they are only general guides to site—specific actions. The job ahead of us now involves three tasks: —Site-specific plans, such as grazing allotment management plans or vehicle route designation; —On-the-ground actions, such as granting mineral leases, developing water sources for wildlife, building fences for livestock pastures or for protecting petroglyphs; and —Keeping people informed of and involved in putting the Plan to work on the ground, and in changing the Plan to meet future needs. -

MASTER HIKE Filecomp

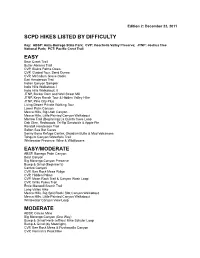

Edition 2: December 22, 2011 SCPD HIKES LISTED BY DIFFICULTY Key: ABSP: Anza-Borrego State Park; CVP: Coachella Valley Preserve; JTNP: Joshua Tree National Park; PCT: Pacific Crest Trail EASY Bear Creek Trail Butler-Abrams Trail CVP, Biskra Palms Oasis CVP, Guided Tour, Sand Dunes CVP, McCallum Grove Oasis Earl Henderson Trail Indian Canyon Sampler Indio Hills Walkabout, I Indio Hills Walkabout, II JTNP, Barker Dam and Wall Street Mill JTNP, Keys Ranch Tour & Hidden Valley Hike JTNP, Pine City Plus Living Desert Private Walking Tour Lower Palm Canyon Mecca Hills, Big Utah Canyon Mecca Hills, Little Painted Canyon Walkabout Morrow Trail (Beginning) La Quinta Cove Loop Oak Glen, Redwoods, Tri-Tip Sandwich & Apple Pie Randall Henderson Trail Salton Sea Bat Caves Sonny Bono Refuge Center, Obsidian Butte & Mud Volcanoes Tahquitz Canyon Waterfalls Trail Whitewater Preserve: Wine & Wildflowers EASY/MODERATE ABSP, Borrego Palm Canyon Bear Canyon Big Morongo Canyon Preserve Bump & Grind (Beginner’s) Carrizo Canyon CVP, Bee Rock Mesa Ridge CVP, Hidden Palms CVP, Moon Rock Trail & Canyon Wash Loop CVP, Willis Palms Trail Ernie Maxwell Scenic Trail Long Valley Hike Mecca Hills, Big Split Rock/ Slot Canyon Walkabout Mecca Hills, Little Painted Canyon Walkabout Whitewater Canyon View Loop MODERATE ABSP, Calcite Mine Big Morongo Canyon (One Way) Bump & Grind/ Herb Jeffries/ Mike Schuler Loop Bump & Grind (by Moonlight) CVP, Bee Rock Mesa & Pushawalla Canyon CVP, Herman’s Peak Hike CVP, Horseshoe Palms Hike CVP, Pushawalla Canyon Eisenhower Peak Loop, -

City of Palm Springs Greenhouse Gas Inventory

City of Palm Springs Greenhouse Gas Inventory City of Palm Springs October 26, 2010 340 S. Farrell Drive, Suite A210 Palm Springs, California 92262 ADMINISTRATIVE DRAFT Greenhouse Gas Inventory City of Palm Springs, California Prepared for: City of Palm Springs 3200 East Tahquitz Canyon Way Palm Springs, CA 92262 760-323-8299 Contact: Michele Catherine Mician, MS Manager, Office of Sustainability Prepared by: Michael Brandman Associates 340 S. Farrell Drive, Suite A210 Palm Springs, CA 92262 Contact: Frank Coyle, REA Author: Cori Wilson Project Number: 02270004 October 26, 2010 City of Palm Springs Greenhouse Gas Inventory Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS Section 1: Executive Summary............................................................................................ 1 Section 2: Introduction.........................................................................................................3 2.1 - Purpose of the Inventory..................................................................................... 3 2.2 - About the Inventory............................................................................................. 4 2.3 - City of Palm Springs............................................................................................ 5 2.4 - Climate Change Background .............................................................................. 9 Climate Change............................................................................................... 9 Greenhouse Gases ......................................................................................