Northeast Michigan Integrated Assessment Final Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ICF Marathon Rules

INTERNATIONAL CANOE FEDERATION CANOE MARATHON COMPETITION RULES 2017 Taking effect from 1 January, 2017 ICF Canoe Marathon Competition Rules 2017 1 INTRODUCTION The purpose of this document is to provide the rules that govern the way of running Canoe Marathon ICF competitions. LANGUAGE The English written language is the only acceptable language for all official communications relating to these Competition Rules and the conduct of all Canoe Marathon ICF competitions. For the sake of consistency, British spelling, punctuation and grammatical conventions have been used throughout. Any word which may imply the masculine gender also includes the feminine. COPYRIGHT These rules may be photocopied. Great care has been taken in typing and checking the rules and the original text is available on the ICF website www.canoeicf.com. Please do not re-set in type without consultation. ICF Canoe Marathon Competition Rules 2017 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Article Page CHAPTER I - GENERAL REGULATIONS ........................................ 5 1 DEFINITION OF CANOE MARATHON ........................... 5 2 INTERNATIONAL COMPETITIONS ............................... 5 3 COMPETITORS .............................................................. 5 4 CLASSES ........................................................................ 7 5 INTERNATIONAL COMPETITION CALENDAR ............. 7 CHAPTER II – CLASSES AND ......................................................... 8 BUILDING RULES ............................................................................ 8 6 LIMITATIONS -

Software Design & Architecture

Software System/Design & Architecture Eng.Muhammad Fahad Khan Assistant Professor Department of Software Engineering Sessional Marks • Midterm 20% • Final 40% • Assignment + Quizez 20 % • Lab Work 10 % • Presentations 10 % Software System Design & Architecture (SE-304) Course Content Design Design is the creation of a plan or convention for the construction of an object or a system (as in architectural blueprints, engineering drawing , business process, circuit diagrams and sewing patterns). OR Another definition for design is a roadmap or a strategic approach for someone to achieve a unique expectation. It defines the specifications, plans, parameters, costs, activities, processes and how and what to do within legal, political, social, environmental, safety and economic constraints in achieving that objective. Approaches to Design • A design approach is a general philosophy that may or may not include a guide for specific methods. Some are to guide the overall goal of the design. Other approaches are to guide the tendencies of the designer. A combination of approaches may be used if they don't conflict. • Some popular approaches include: • KISS principle, (Keep it Simple Stupid), which strives to eliminate unnecessary complications. • There is more than one way to do it(TIMTOWTDI), a philosophy to allow multiple methods of doing the same thing. • Use-centered design, which focuses on the goals and tasks associated with the use of the artifact, rather than focusing on the end user. • User-centered design, which focuses on the needs, wants, and limitations of the end user of the designed artifact. • Critical design uses designed artifacts as an embodied critique or commentary on existing values, morals, and practices in a culture. -

The Influence of Three Instructional Strategies on The

THE INFLUENCE OF THREE INSTRUCTIONAL STRATEGIES ON THE PERFORMANCE OF THE OVERARM THROW DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the School of Physical Activity and Educational Services at The Ohio State University By Kevin Michael Lorson * * * * THE OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY 2003 Dissertation Committee: Approved by: Dr. Jackie Goodway, Advisor ______________________ Dr. Phillip Ward Adviser Dr. Tim Barrett College of Education ABSTRACT The purpose of this study was to examine the influence of three instructional strategies on the performance of the overarm throw. A secondary purpose of the study is to examine the influence of gender and instruction on throwing performance. The three instructional strategies were a critical cue (CUE), a biomechanical (BP), and typical physical education approach (TPE). The CUE strategy consisted of three cues: laser beams, long step, and turn your hips fast. The BP strategy was a translation of biomechanical information into a four-stage strategy. The TPE strategy was based on Graham and colleagues (2001) critical elements. The dependent measures of throwing performance were body component levels, component levels during gameplay, and ball velocity. Participants (n=124) from six first and second-grade classes were systematically assigned to an instructional approach. Mean body component levels for the step, trunk, humerus and forearm along with mean recorded ball velocity were calculated from the 10 throwing trials at the pretest, posttest, and retention test. Additionally, participants’ body component levels for the step, trunk, and forearm demonstrated in a throwing game were correlated with the body component levels demonstrated during practice. -

CANOE SPRINT COACHING MANUAL LEVEL 2 and 3

COACHES EDUCATION PROGRAMME CANOE SPRINT COACHING MANUAL LEVEL 2 and 3 Csaba Szanto 1 REFERENCES OF OTHER EXPERTS The presented Education Program has been reviewed with regards the content, methodic approach, description and general design. In accordance with above mentioned criteria the program completely corresponds to world wide standard and meet expectations of practice. Several suggestions concerned the illustrations and technical details were transmitted to the author. CONCLUSION: The reviewed program is recommended for sharing among canoe- kayak coaches of appropriate level of competence and is worthy for approval. Reviewer: Prof. Vladimir Issurin, Ph.D. Wingate Institute for Physical Education and Sport, Netanya, Israel Csaba Szanto's work is a great book that discusses every little detail, covering the basic knowledge of kayaking canoeing science. The book provides a wide range of information for understanding, implement and teaching of our sport. This book is mastery in compliance with national and international level education, a great help for teachers and coaches fill the gap which has long been waiting for. Zoltan Bako Master Coach, Canoe-kayak Teacher at ICF Coaching Course Level 3 at the Semmelweis University, Budapest Hungary FOREWORD Csaba Szanto has obtained unique experience in the field of canoeing. Probably there is no other specialist in the canoe sport, who has served and worked in so many places and so many different functions. Csaba coached Olympic champions, but he has been successful with beginners as well. He contributed to the development of the canoe sport in many countries throughout the world. Csaba Szanto wrote this book using the in depth knowledge he has of the sport. -

Cambridge Canoe Club Newsletter

Christmas Party CAMBRIDGE The CCC Christmas Party already promises to be the great social event of the new year! It is such a runaway success CANOE CLUB that it already is fully booked , but this information is enclosed for those lucky few who are on the guest list. NEWSLETTER This year’s Christmas party will be held at Peterhouse College, Trumpington Street, on the 20th of January at CHRISTMAS SPECIAL 7:00 pm. The dress code (strictly enforced by bouncers wielding paddles) is black tie. The menu is: http://www.cambridgecanoeclub.org.uk Carrot & Ginger Soup To get the club's diary of events and ad-hoc messages — about club activities by e-mail please send a blank Corn-fed Chicken Supreme Stuffed with Chestnuts & Stilton with port wine sauce message to: Creamed Carrots [email protected] Calabrese florets with basil chiffonade In case you already didn’t know, canoeing is an assumed risk, Parisienne Potatoes water contact sport. — Pear & Cardamon Tart with Saffron Creme Fraiche December 2005 — Cheese & Biscuits If you received this Newsletter by post and you would be — happy to view your Newsletter on the Cambridge Canoe Coffee & Mints Club website (with all the photos in glorious colour!) then please advise the Membership Secretary. Contact details Club Diary are shown at the end of this Newsletter. Chairman’s Chat Hare & Hound Races Three races down, four to go, so you can start now and be My first Chairman’s Chat and just in time to wish you all eligible for one of our much sought after prizes, although a very Happy Christmas! not certain what they will be yet. -

Sept 2019 Final.Pdf

Volume 5, Issue 5 | September 2019 PADDLEACA | Canoe - Kayak - SUP - Raft - Rescue Nevin Harrison becomes first American woman to win World Sprint Canoe Title (See story on page 51) Coastal Kayaking in South China Sea ACA Releases Multi-use Waterway Videos Instructors of the Month TABLE of CONTENTS ACA News Education 3 Mission Statement & Governance 20 ACA Develops Multi-use Waterways Videos 5 Meet Your ACA Staff 21 Instructors of the Month 7 ACA Partners 25 Swift Water Training Vital, Fun 8 2019 ACA Instructor Trainer Conference 27 Providing Unique Training for Guides 29 Voyage of the Green Argosy 31 ACA Pro School Spotlight Stewardship 10 Paddle Green Spotlight: CFS Grant Recipients Universal 17 Willamette River Fest Grows 33 Universal Paddling Workshops 34 Updated Universal Program 37 Equipment Review Marcel Bieg photo News Near You Competition 37 State Updates 51 Rising Teen Makes History 44 New Mexico Club Provides Summer Clinic 53 Athletes Excite with Excellent Performances 65 Upcoming Races & Events Membership 46 ACA Member Benefit Paddling History 47 Member Photo of the Month 58 1898 ACA Meet 48 ACA Outfitter Spotlight www.americancanoe.org PADDLE | September 2019 | Page 2 NATIONAL STAFF BOARD OF DIRECTORS Beth Spilman - Interim Executive Director Executive Committee Marcel Bieg - Western States Outreach Director President - Robin Pope (NC) JD Martin - Financial Coordinator Vice President - Lili Colby (MA) Kelsey Bracewell - SEI Manager Treasurer - Trey Knight (TN) Dave Burden - International Paddlesports Ambassador Secretary -

Axiomatic Design of Space Life Support Systems

47th International Conference on Environmental Systems ICES-2017-82 16-20 July 2017, Charleston, South Carolina Axiomatic Design of Space Life Support Systems Harry W. Jones1 NASA Ames Research Center, Moffett Field, CA, 94035-0001 Systems engineering is an organized way to design and develop systems, but the initial system design concepts are usually seen as the products of unexplained but highly creative intuition. Axiomatic design is a mathematical approach to produce and compare system architectures. The two axioms are: - Maintain the independence of the functional requirements. - Minimize the information content (or complexity) of the design. The first axiom generates good system design structures and the second axiom ranks them. The closed system human life support architecture now implemented in the International Space Station has been essentially unchanged for fifty years. In contrast, brief missions such as Apollo and Shuttle have used open loop life support. As mission length increases, greater system closure and increased recycling become more cost-effective. Closure can be gradually increased, first recycling humidity condensate, then hygiene waste water, urine, carbon dioxide, and water recovery brine. A long term space station or planetary base could implement nearly full closure, including food production. Dynamic systems theory supports the axioms by showing that fewer requirements, fewer subsystems, and fewer interconnections all increase system stability. If systems are too complex and interconnected, reliability is reduced and operations and maintenance become more difficult. Using axiomatic design shows how the mission duration and other requirements determine the best life support system design including the degree of closure. Nomenclature DP = Design Parameter DSM = Design Structure Matrix EVA = ExtraVehicular Activity FR = Functional Requirement KISS = Keep it simple, stupid QFD = Quality Function Deployment I. -

Minutes 141002

Bike Friendly Kalamazoo October 2, 2014 Session Meeting Minutes KRESA West Campus Attendees Emily Betros, Head Start Family Advocate, KRESA Marsha Drouin, Treasurer, Richland Township Jim Hoekstra, Traffic Engineer, City of Kalamazoo & KCRC Pastor Dale Krueger, Member, Kalamazoo Bicycle Club Laura J. Lam, Director of Community Planning & Development, City of Kalamazoo Greg Milliken, Planning Director, Oshtemo Township; Zoning Administrator and Planning, Kalamazoo Township Carl Newton, Mayor, City of Galesburg Ron Reid, Supervisor, Kalamazoo Township Paul Selden, Director of Road Safety, KBC; Member, TriKats Ray Waurio, Deputy Director of Streets & Parks Maintenance, City of Portage John Zull, District 11 Kalamazoo County Commissioner Session Goals: - Organize suggested topic of a “typical” local non-motorized plan (NMP). - Find/assemble suitable content examples for as many of the main sections as possible, online Agenda Welcome and Introductions – Paul Selden Background on Bike Friendly Kalamazoo and BFK’s goals for 2014 BFK: a communications network of volunteer participants/delegates from community stakeholders (for more information, see www.bikefriendlykalamazoo.org) Main 2014 goals include awareness-building, education and route planning In-Session Project Work – Small Group – Paul Selden Participants worked on three mini-projects: a) identifying the table of contents headings under which to consider general ideas and broad considerations previously suggested in the documents entitled “Ideas for Typical Non-Motorized Plan” by Paul Selden and “Thoughts on Non-Motorized Plans” by Norm Cox; b) categorizing previously suggested NMP topics under their related table of contents headings; and, c) finding suitable content examples representing each of the sections in the table of contents. The work product from each small group follows on separate pages, beginning on the next page. -

The Kiss Principle in Survey Design: Question Length and Data Quality

Survey Measurement Sociological Methodology 2016, Vol. 46(1) 121–152 Ó American Sociological Association 2016 DOI: 10.1177/0081175016641714 4 http://sm.sagepub.com THE KISS PRINCIPLE IN SURVEY DESIGN: QUESTION LENGTH AND DATA QUALITY Duane F. Alwin* Brett A. Beattie* Abstract Writings on the optimal length for survey questions are characterized by a variety of perspectives and very little empirical evidence. Where evidence exists, support seems to favor lengthy questions in some cases and shorter ones in others. However, on the basis of theories of the survey response process, the use of an excessive number of words may get in the way of the respondent’s comprehension of the information requested, and because of the cognitive burden of longer questions, there may be increased measure- ment errors. Results are reported from a study of reliability estimates for 426 (exactly replicated) survey questions in face-to-face interviews in six large-scale panel surveys conducted by the University of Michigan’s Survey Research Center. The findings suggest that, at least with respect to some types of survey questions, there are declining levels of reliability for questions with greater numbers of words and provide further support for the advice given to survey researchers that questions should be as short as possible, within constraints defined by survey objectives. Findings rein- force conclusions of previous studies that verbiage in survey questions— either in the question text or in the introduction to the question—has *Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA, USA Corresponding Author: Duane F. Alwin, Pennsylvania State University, 309 Pond Laboratory, University Park, PA 16802, USA Email: [email protected] Downloaded from smx.sagepub.com at ASA - American Sociological Association on September 20, 2016 122 Alwin and Beattie negative consequences for the quality of measurement, thus supporting the KISS principle (“keep it simple, stupid”) concerning simplicity and parsimony. -

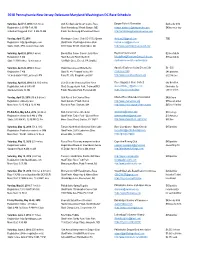

Combined Race Schedule

2018 Pennsylvania-New Jersey-Delaware-Maryland-Washington DC Race Schedule Saturday, April 14, 2018 (16.5 miles) 48th Kenduskeag Stream Canoe Race Bangor Parks & Recreation $20/ea by 4/15 Registration: 6:30 AM-7:30 AM Start: Kendskeag / Finish: Bangor, ME [email protected] $40/ea race day Individual Staggered Start: 8 AM-10 AM Finish: Kenduskeag & Penobscot Rivers http://kenduskeagstreamcanoerace.com Sunday, April 15, 2018 Washington Canoe Club OC1/OC2 Sprints [email protected] TBD Registration: http://paddleguru.com Start/Finish: Washington Canoe Club [email protected] Starts: 9AM - 3PM (no parking at club) 3700 Water St NW, Washington, DC http://www.washingtoncanoeclub.org/ Saturday, April 28, 2018 (5 miles) Bloody Run Canoe Classic Junta River Raystown Canoe Club $20/ea Adults Registration: 8 AM Start: Everett, Finish: Bedford [email protected] $15/ea Adults Start: 11 AM in three 15 min waves 128 Main Street, Everett, PA (shuttle) raystowncanoeclub.com/bloodyrun Saturday, April 28, 2018 (8 miles) Wappingers Creek White Derby Aquatics Explorers Scuba Divers Club $5 - $20 Registration: 7 AM Start: Rt. 44, Pleasant Valley, NY (914) 563-2109 248 paddlers 1st boat starts 8 AM, Last boat 3 PM Fiish: Rt. 376, Poughskeepsi, NY http://www.acquaticexplorers.org at 2016 race Saturday, April 28, 2018 (6 & 19.5 miles) Little D on the Monocacy River Race Race Organizer: Steve Corbett any donation, Registration: nds at 9:45 AM Start: Creagerstown Park, Thurmont MD [email protected] fundraiser for Staggered -

A Framework for a Formal Sovereign Debt Restructuring Mechanism: the KISS Principle (Keep It Simple, Stupid) and Other Guiding Principles

University of Pennsylvania Carey Law School Penn Law: Legal Scholarship Repository Faculty Scholarship at Penn Law Fall 2015 A Framework for a Formal Sovereign Debt Restructuring Mechanism: The KISS Principle (Keep It Simple, Stupid) and Other Guiding Principles Charles W. Mooney Jr. University of Pennsylvania Carey Law School Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.upenn.edu/faculty_scholarship Part of the Banking and Finance Law Commons, Bankruptcy Law Commons, Conflict of Laws Commons, International Economics Commons, International Law Commons, International Relations Commons, Law and Economics Commons, Public Administration Commons, and the Transnational Law Commons Repository Citation Mooney, Charles W. Jr., "A Framework for a Formal Sovereign Debt Restructuring Mechanism: The KISS Principle (Keep It Simple, Stupid) and Other Guiding Principles" (2015). Faculty Scholarship at Penn Law. 1547. https://scholarship.law.upenn.edu/faculty_scholarship/1547 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Penn Law: Legal Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship at Penn Law by an authorized administrator of Penn Law: Legal Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A FRAMEWORK FOR A FORMAL SOVEREIGN DEBT RESTRUCTURING MECHANISM: THE KISS PRINCIPLE (KEEP IT SIMPLE, STUPID) AND OTHER GUIDING PRINCIPLES Charles W. Mooney, Jr.* TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ................................................. 58 I. APPROACHES TO SOVEREIGN DEBT RESTRUCTURING .... 69 A. “Contractual” (or “Private-Law”) and “Statutory” (or “Public-Law”) Approaches to Restructuring Mechanisms ........................................ 70 B. Implementation and Effectiveness of Statutory Approach .......................................... 72 1. Stand-alone SDRL ............................. 72 2. Multilateral or Reciprocal Approaches .......... 73 II. SOVEREIGN DEBT RESTRUCTURING AS A VIRTUAL AGGREGATED COLLECTIVE ACTION CLAUSE ........... -

Győr, Hungary 11-13 September, 2015 Icf Canoe

ICF CANOE MARATHON WORLD CHAMPIONSHIPS BULLETIN No. 1. GYŐR, HUNGARY 11-13 SEPTEMBER, 2015 GREETINGS FROM THE MAYOR Győr has always been home to the training of sport icons: lots of champions have started their sports career or arrived to the top of it here. In the „City of Rivers” kayak and canoe competitors of Győr representing the most successful sport branch of Hungary have several times achieved smashing victories and classified very well in prestigious competitions. Upbringing of youth teams has always been a priority to Győr, so development in sportslife is unbroken here. Probably it is not just a pure coincidence that Győr can be home to such an important event in the kayak and canoeing sport for the third time, and also host to the first paracanoe competitions. I hope that our Guests will have time to discover the beauties of our City and have some days full of sports events and wonderful experiences. Zsolt Borkai Mayor BEFORE BREAKTHROUGH In 2015 the marathon canoe racing returns to Győr, the town of waters, where after 1999 and 2007 we can host the world championships in this discipline exceptionally already for the third time. The Hungarian canoe sport at the peak of its success is getting ready for the big shot, as we wish to organise the best ever marathon race in September, which marvels the whole world. The county seat of West Hungary really has excellent water features, the races run almost through the downtown area. And Győr is moreover a real sport town, where great many fans know and follow the events of the canoe sport and where full support is given to such big-scale events.