The Purpose, Function, and Performance of Streetcar Transit in the Modern U.S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Multi‐Disciplinary Commentaries on a Blueprint for Prosperity

June 2015 Multi‐disciplinary Commentaries on a Blueprint for Prosperity Foreword The City of Memphis’ Blue Print for Prosperity is a city initiated effort to partner with other local initiatives, organizations and agencies to increase the wealth among low income citizens, increase their resiliency to meet daily financial exigencies and reduce poverty. A number of factors contribute to those challenges. Thus any successful effort to address them requires a multidisciplinary approach. In June 2014, a set of researchers at the University of Memphis across a range of academic colleges and departments was invited to discuss approaches to wealth creation and poverty reduction for the various perspectives of their various disciplines. Based on that conversation, they were asked to submit policy briefs from those perspectives with recommendations to contribute to a community process to produce a plan for action. The following report summarizes and provides those briefs. Participants in the report and their contributions include: David Cox, Ph.D., Department of Public and Nonprofit Administration, School of Urban Affairs and Public Policy, College of Arts and Sciences. Project Director Debra Bartelli, DrPH., Division of Epidemiology, Biostatistics, and Environmental Health, School of Public Health. Health Care/Mental Health and Wellness Strand Cyril Chang, Ph.D., Department of Economics, Fogelman School of Business and Economics. Health Care/Mental Health and Wellness Strand Beverly Cross, Ph.D., Department of Instruction and Curriculum Leadership, College of Education, Health and Human Sciences. Education and Early Development Strand Elena Delevega, Ph.D., Department of Social Work, School of Urban Affairs and Public Policy, College of Arts and Sciences. -

FY2020 Financial Forecast Executive Summary April 2019

PRR 2019-519 Budget and Grants Administration Department Tri-County Metropolitan Transportation District of Oregon FINANCIAL FORECAST FY2020 BUDGET FORECAST WITH FINANCIAL ANALYSIS PRR 2019-519 PRR 2019-519 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 Section 1 – ECONOMIC INDICATORS 5 Section 2 – LONG-TERM PROJECTIONS 11 Section 3 – FY2019 FINANCIAL FORECAST ASSUMPTIONS REPORT 15 A. Revenue Forecast Assumptions 1. Payroll Tax Revenues (Employer and Municipal) 19 2. Self-Employment Tax Revenues 21 3. State-In-Lieu of Tax Revenues 21 4. Employee Payroll Tax Revenues – Special Transportation Improvement Fund 22 5. Passenger Revenues 23 6. Ridership Forecasts 24 7. Fare Agreements and Programs 25 8. Fare Revenue Conclusions 27 9. Other Operating Revenues 27 10. Interest Earnings 28 11. Grant and Capital Project Reimbursements 29 12. Accessible Transportation Program (ATP) Funds 31 13. Funding Exchanges 31 14. Undistributed Budgetary Fund Balance 31 15. Total Revenues 32 B. System Operating Maintenance and Capital Cost Assumptions 16. Cost Inflation 33 17. Wages and Salaries 33 18. Health Plans 34 19. Workers Compensation 34 20. Pensions 35 21. Retiree Medical (Other Post-Employment Benefits [“OPEB”]) 36 22. Diesel Fuel 37 23. Electricity and Other Utilities 37 24. Other Materials and Services 38 25. Bus Operations: Existing Services 38 26. Accessible Transportation Program (ATP or “LIFT”) 38 27. Light Rail Operations: Existing Services 40 28. Commuter Rail Operations 41 29. Streetcar Operations: Existing Services 41 i PRR 2019-519 Table of Contents (continued) 30. Facilities 42 31. Security and Operations Support 42 32. Engineering & Construction Division 42 33. General & Administration 42 34. Capital Improvement Program 43 C. -

10 – Eurocruise - Porto Part 4 - Heritage Streetcar Operations

10 – Eurocruise - Porto Part 4 - Heritage Streetcar Operations On Wednesday morning Luis joined us at breakfast in our hotel, and we walked a couple of blocks in a light fog to a stop on the 22 line. The STCP heritage system consists of three routes, numbered 1, 18 and 22. The first two are similar to corresponding services from the days when standard- gauge streetcars were the most important element in Porto’s transit system. See http://www.urbanrail.net/eu/pt/porto/porto-tram.htm. The three connecting heritage lines run every half-hour, 7 days per week, starting a little after the morning rush hour. Routes 1 and 18 are single track with passing sidings, while the 22 is a one-way loop, with a short single-track stub at its outer end. At its Carmo end the 18 also traverses a one-way loop through various streets. Like Lisbon, the tramway operated a combination of single- and double- truck Brill-type cars in its heyday, but now regular service consists of only the deck-roofed 4-wheelers, which have been equipped with magnetic track brakes. Four such units are operated each day, as the 1 line is sufficiently long to need two cars. The cars on the road on Wednesday were 131, 205, 213 and 220. All were built by the CCFP (Porto’s Carris) from Brill blueprints. The 131 was completed in 1910, while the others came out of the shops in the late 1930s-early 1940s. Porto also has an excellent tram museum, which is adjacent to the Massarelos carhouse, where the rolling stock for the heritage operation is maintained. -

NS Streetcar Line Portland, Oregon

Portland State University PDXScholar Urban Studies and Planning Faculty Nohad A. Toulan School of Urban Studies and Publications and Presentations Planning 6-24-2014 Do TODs Make a Difference? NS Streetcar Line Portland, Oregon Jenny H. Liu Portland State University, [email protected] Zakari Mumuni Portland State University Matt Berggren Portland State University Matt Miller University of Utah Arthur C. Nelson University of Utah SeeFollow next this page and for additional additional works authors at: https:/ /pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/usp_fac Part of the Transportation Commons, Urban Studies Commons, and the Urban Studies and Planning Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Citation Details Liu, Jenny H.; Mumuni, Zakari; Berggren, Matt; Miller, Matt; Nelson, Arthur C.; and Ewing, Reid, "Do TODs Make a Difference? NS Streetcar Line Portland, Oregon" (2014). Urban Studies and Planning Faculty Publications and Presentations. 124. https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/usp_fac/124 This Report is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Urban Studies and Planning Faculty Publications and Presentations by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Authors Jenny H. Liu, Zakari Mumuni, Matt Berggren, Matt Miller, Arthur C. Nelson, and Reid Ewing This report is available at PDXScholar: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/usp_fac/124 NS Streetcar Line Portland, Oregon Do TODs Make a Difference? Jenny H. Liu, Zakari Mumuni, Matt Berggren, Matt Miller, Arthur C. Nelson & Reid Ewing Portland State University 6/24/2014 ______________________________________________________________________________ DO TODs MAKE A DIFFERENCE? 1 of 35 Section 1-INTRODUCTION 2 of 35 ______________________________________________________________________________ Table of Contents 1-INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................................................... -

SHELBY COUNTY COMMISSIONERS Van D

THIS PRELIMINARY OFFICIAL STATEMENT IS DATED JANUARY 23, 2019 NEW ISSUE - BOOK-ENTRY ONLY RATINGS: See “RATINGS” herein. In the opinion of Bond Counsel, under existing laws, regulations, rulings, and judicial decisions and assuming the accuracy of certain representations and continuous compliance with certain covenants described herein, interest on the Series 2019 Bonds (defined below) is excludable from gross income under federal income tax laws pursuant to Section 103 of the Internal Revenue Code of 1986, as amended to the date of delivery of the Series 2019 Bonds, and such interest is not a specific preference item for purposes of the federal alternative minimum tax. Bond Counsel is further of the opinion that, under existing law, the Series 2019 Bonds and the income therefrom shall be free from all state, county and municipal taxation in the State of Tennessee, except inheritance, transfer and estate taxes, and Tennessee franchise and excise taxes. For a more complete description, see “TAX MATTERS” herein. SHELBY COUNTY, TENNESSEE $170,865,000* $72,460,000* GENERAL OBLIGATION PUBLIC IMPROVEMENT GENERAL OBLIGATION REFUNDING BONDS, AND SCHOOL BONDS, 2019 SERIES A 2019 SERIES B Dated: Date of Delivery Due: As shown on the inside cover This Official Statement relates to the issuance by the County of Shelby, Tennessee (the “County”) of $170,865,000* in aggregate principal amount of General Obligation Public Improvement and School Bonds, 2019 Series A (the “Series 2019A Bonds”) and $72,460,000* in aggregate principal amount of General Obligation Refunding Bonds, 2019 Series B (the “Series 2019B Bonds”, and together with the Series 2019A Bonds the “Series 2019 Bonds”). -

City of Wilsonville Transit Master Plan

City of Wilsonville Transit Master Plan CONVENIENCE SAFETY RELIABILITY EFFICIENCY FISCAL RESPONSIBILITY FRIENDLY SERVICE EQUITY & ACCESS ENVIRONMENTAL RESPONSIBILITY JUNE 2017 Acknowledgements The City of Wilsonville would like to acknowledge the following for their dedication to the development of this Transit Master Plan. Their insight and outlook toward the future of this City helped create a comprehensive plan that represents the needs of employers, residents and visitors of Wilsonville. Transit Master Plan Task Force Planning Commission Julie Fitzgerald, Chair* Jerry Greenfield, Chair Kristin Akervall Eric Postma, Vice Chair Caroline Berry Al Levit Paul Diller Phyllis Millan Lynnda Hale Peter Hurley Barb Leisy Simon Springall Peter Rapley Kamran Mesbah Pat Rehberg Jean Tsokos City Staff Stephanie Yager Dwight Brashear, Transit Director Eric Loomis, Operations Manager City Council Scott Simonton, Fleet Manager Tim Knapp, Mayor Gregg Johansen, Transit Field Supervisor Scott Star, President Patrick Edwards, Transit Field Supervisor Kristin Akervall Nicole Hendrix, Transit Management Analyst Charlotte Lehan Michelle Marston, Transit Program Coordinator Susie Stevens Brad Dillingham, Transit Planning Intern Julie Fitzgerald* Chris Neamtzu, Planning Director Charlie Tso, Assistant Planner Consultants Susan Cole, Finance Director Jarrett Walker Keith Katko, Finance Operations Manager Michelle Poyourow Tami Bergeron, Planning Administration Assistant Christian L Watchie Amanda Guile-Hinman, Assistant City Attorney Ellen Teninty Stephan Lashbrook, -

Paris: Trams Key to Multi-Modal Success

THE INTERNATIONAL LIGHT RAIL MAGAZINE www.lrta.org www.tautonline.com JANUARY 2016 NO. 937 PARIS: TRAMS KEY TO MULTI-MODAL SUCCESS Innsbruck tramway enjoys upgrades and expansion Bombardier sells rail division stake Brussels: EUR5.2bn investment plan First UK Citylink tram-train arrives ISSN 1460-8324 £4.25 Sound Transit Swift Rail 01 Seattle ‘goes large’ A new approach for with light rail plans UK suburban lines 9 771460 832043 For booking and sponsorship opportunities please call +44 (0) 1733 367600 or visit www.mainspring.co.uk 27-28 July 2016 Conference Aston, Birmingham, UK The 11th Annual UK Light Rail Conference and exhibition brings together over 250 decision-makers for two days of open debate covering all aspects of light rail operations and development. Delegates can explore the latest industry innovation within the event’s exhibition area and examine LRT’s role in alleviating congestion in our towns and cities and its potential for driving economic growth. VVoices from the industry… “On behalf of UKTram specifically “We are really pleased to have and the industry as a whole I send “Thank you for a brilliant welcomed the conference to the my sincere thanks for such a great conference. The dinner was really city and to help to grow it over the event. Everything about it oozed enjoyable and I just wanted to thank last two years. It’s been a pleasure quality. I think that such an event you and your team for all your hard to partner with you and the team, shows any doubters that light rail work in making the event a success. -

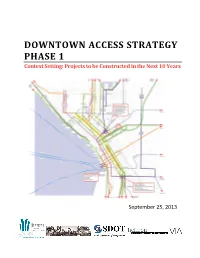

Downtown Access Strategy Phase 1 Context Setting: Projects to Be Constructed in the Next 10 Years Table of Contents

DOWNTOWN ACCESS STRATEGY PHASE 1 Context Setting: Projects to be Constructed in the Next 10 Years September 25, 2013 Downtown Access Strategy Phase 1 Context Setting: Projects to be Constructed in the Next 10 Years Table of Contents I. Introduction ................................................................................................. 1 II. Review of Existing Plans, Projects, and Programs ......................................... 2 III. Potential Construction Concerns and Opportunities .................................. 3 A. Existing Construction Planning Tools 3 B. SDOT’s Construction Hub Coordination Program 4 C. Construction Mitigation Strategies Used by Other Cities 7 D. Potential Construction Conflicts and Opportunities 10 IV. Future Transportation Network Opportunities ......................................... 12 A. North Downtown 12 B. Denny Triangle / Westlake Hub 14 C. Pioneer Square / Chinatown-ID 15 D. Downtown Core and Waterfront 16 V. Future Phases of Downtown Access Strategy ............................................. 18 A. Framework for Phase 2 (2014 through 2016) 18 B. Framework for Phase 3 (Beyond 2016) 19 - i - September 25, 2013 Downtown Access Strategy Phase 1 Context Setting: Projects to be Constructed in the Next 10 Years I. INTRODUCTION Many important and long planned transportation and development projects are scheduled for con- struction in Downtown Seattle in the coming years. While these investments are essential to support economic development and job growth and to enhance Downtown’s stature as the region’s premier location to live, work, shop and play, in the short-term they present complicated challenges for con- venient and reliable access to and through Downtown. The Downtown Seattle Association (DSA) and its partners, Historic South Downtown (HSD) and the Seat- tle Department of Transportation (SDOT), seek to ensure that Downtown Seattle survives and prospers during the extraordinarily high level of construction activity that will occur in the coming years. -

Eastwick Intermodal Center

Eastwick Intermodal Center January 2020 New vo,k City • p-~ d DELAWARE VALLEY DVRPC's vision for the Greater Ph iladelphia Region ~ is a prosperous, innovative, equitable, resilient, and fJ REGl!rpc sustainable region that increases mobility choices PLANNING COMMISSION by investing in a safe and modern transportation system; Ni that protects and preserves our nat ural resources w hile creating healthy communities; and that fosters greater opportunities for all. DVRPC's mission is to achieve this vision by convening the widest array of partners to inform and facilitate data-driven decision-making. We are engaged across the region, and strive to be lea ders and innovators, exploring new ideas and creating best practices. TITLE VI COMPLIANCE / DVRPC fully complies with Title VJ of the Civil Rights Act of 7964, the Civil Rights Restoration Act of 7987, Executive Order 72898 on Environmental Justice, and related nondiscrimination mandates in all programs and activities. DVRPC's website, www.dvrpc.org, may be translated into multiple languages. Publications and other public documents can usually be made available in alternative languages and formats, if requested. DVRPC's public meetings are always held in ADA-accessible facilities, and held in transit-accessible locations whenever possible. Translation, interpretation, or other auxiliary services can be provided to individuals who submit a request at least seven days prior to a public meeting. Translation and interpretation services for DVRPC's projects, products, and planning processes are available, generally free of charge, by calling (275) 592-7800. All requests will be accommodated to the greatest extent possible. Any person who believes they have been aggrieved by an unlawful discriminatory practice by DVRPC under Title VI has a right to file a formal complaint. -

Seattle Center City Connector Transit Study LPA Report

The Seattle Department of Transportation Seattle Center City Connector Transit Study Locally Preferred Alternative (LPA) R e port Executive Summary August 2014 in association with: URS Shiels Obletz Johnsen CH2MHill Natalie Quick Consulting John Parker Consulting BERK Consulting VIA Architecture Alta Planning + Design DKS Associates I | LOCALLY PREFERRED ALTERNATIVE REPORT ― EXECUTIVE SUMMARY LTK Cover image from SDOT Seattle Center City Connector Transit Study Executive Summary Volume I: LPA Report 1. Project Overview 2. Purpose and Need 3. Evaluation Framework 4. Evaluation of Alternatives 5. Summary of Tier 1 Screening and Tier 2 Evaluation Results and Public Input 6. Recommended Locally Preferred Alternative 7. Next Steps Volume I Appendix A: Project Purpose and Need Volume II: Detailed Evaluation Report 1. Project Overview 2. Evaluation Framework and Public Outreach 3. Initial Screening of Alternatives (Purpose and Need) 4. Summary of Tier 1 Alternatives and Evaluation Results 5. East-West Connection Assessment 6. Description of Tier 2 Alternatives 7. Tier 2 Evaluation Results 8. Tier 2 Public Outreach Summary 9. Tier 2 Recommendation Volume II Technical Appendices (Methodology and Detailed Results) Appendix A: Ridership Projections Appendix B: Additional Ridership Markets: Visitors and Special Events Appendix C: Operating and Maintenance Cost Methodology and Estimates Appendix D: Loading Analysis Appendix E: Capital Cost Methodology and Estimates Appendix F: Utility Impacts Assessment Appendix G: Traffic Analysis Appendix H Evaluation -

Media Clips Template

The Oregonian With re-election bid gone, what can Charlie Hales accomplish? By Andrew Theen October 28, 2015 Charlie Hales is a free agent. Instead of running for re-election, Hales said Monday that he's ready to tackle affordable housing, homelessness, gang violence and the city's blueprint for the next 20 years of growth. He didn't provide many details Monday, and he and his spokesman declined to provide more information Tuesday. But current and former City Hall staffers agreed that Hales now has more room to get things done, and can look to his last two predecessors, Sam Adams and Tom Potter, for models of successes and failures. "You can really break through some of the walls that people put up because people say, 'It's just politics as usual,'" said Austin Raglione, Potter's former chief of staff. Susan Anderson, director of the Bureau of Planning & Sustainability who's been in city government for two decades, said Hales still has credibility and can now be bolder. "You can take some chances," she said. Commissioner Nick Fish said Hales could look to Adams, who followed his July 2011 decision to not run with a "burst of productive energy." In his last year in office, Adams proposed a budget that included a more than $7 million bailout for Portland public schools. He also conceived of the Arts Tax, expelled Occupy Portland demonstrators from downtown parks, and created a new urban renewal district, though Hales disbanded it. On the other hand, Adams wasn't able to push through a renovation of Veterans Memorial Coliseum, though, or a plan to build a $62 million Sustainability Center. -

The Transfer Newsletter Spring 2013.Cdr

Oregon Electric Railway Historical Society Volume 18 503 Issue 2 Spring 2013 Reminder to members: Please be sure your dues In this issue: are up to date. 2013 dues were due Jan 1, 2013. Willamette Shore Trolley - Back on Track.................................1 If it has been longer than one year since you renewed, Interpretive Center Update - Greg Bonn...............................2 go to our website: oerhs.org and download an Vintage Trolley History - Richard Thompson.............................3 application by clicking: Become a Member Pacific NW Transit Update - Roy Bonn...............................8 Spotlight on Members: Charlie Philpot ................................11 Setting New Poles - Greg Bonn..............................................12 Willamette Shore Trolley ....back on track! See this issue in color on line at oerhs.org/transfer miles from Lake Oswego to Riverwood Crossing with an ultimate plan to extend to Portland. Also see the article on page 3 on the history of the cars of Vintage Trolley. Dave Rowe installing wires from Generator to Trolley. Hal Rosene at the controls of 514 on a training run emerging Gage Giest painting from the Elk Rock Tunnel on the Willamette Shore line. the front of Trolley. Wayne Jones photo The Flume car in background will be After a several-year hiatus, the Willamette Shore our emergency tow Trolley is just about ready to roll. Last minute electrical and vehicle if the Trolley mechanical details and regulatory compliance testing are breaks down on the nearing completion. With many stakeholders involved and mainline. many technical issues that had to be overcome, it has been a challenge to get the system to the 100% state. Dave Rowe and his team have been working long hours to overcome the obstacles of getting Gomaco built Vintage Trolley #514, its Doug Allen removing old stickers from side tag-along generator, track work, electrical systems, crew of Trolley training, safety compliance issues, propulsion, braking, and so many other details to a satisfactory state to begin revenue service.