The American Revolution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 4-5: Study Focus • Essay Format Essential Questions 9

Chapter 4-5: Study Focus • Essay Format Essential Questions 9. What were The Coercive Acts of 19. What were the central 1774 (the Intolerable Acts) and why ideas and grievances expressed Content Standard 1: The student were they implemented? will analyze the foundations of in the Declaration of Indepen- dence? the United States by examining 10. Why was the First Continental the causes, events, and ideolo- Congress formed? gies which led to the American 20. How did John Locke‛s the- Revolution. ory of natural rights infl uence 11. What happened at the Battles of the Declaration of Indepen- Lexington and Concord and what was dence? 1. What were the political and eco- the impact on colonial resistance? nomic consequences of the French and Indian War on the 13 colo- 21. What is the concept of the 12. What was the purpose of Patrick social contract? nies? Henry‛s Give Me Liberty or Give Me Death speech? 2. What were the British imperial 22. What are the main ideals policies of requiring the colonies to 13. What was the purpose of and established in the Declaration pay a share of the costs of defend- main arguments made by Thomas of Independence? ing the British Empire? Paine‛s pamphlet Common Sense? 23. What were the contribu- 3. What the Albany Plan of Union? 14. What were the points of views tions of Thomas Jefferson of the Patriots and the Loyalists and the Committee of Five in 4. What was the signifi cance of the about independence? drafting the Declaration of Proclamation of 1763? Independence. -

Section 7-1: the Revolution Begins

Name: Date: Chapter 7 Study Guide Section 7-1: The Revolution Begins Fill in the blanks: 1. The First Continental Congress was a meeting of delegates from various colonies in September of 1774 to discuss the ongoing crisis with Britain. 2. The Minutemen were members of the Massachusetts militia that were considered ready to fight at a moment’s notice. 3. General Thomas Gage was the British military governor of Massachusetts, and ordered the seizure of the militia’s weapons, ammunition, and supplies at Concord. 4. The towns of Lexington and Concord saw the first fighting of the American Revolution. 5. The “Shot heard ‘round the world” was the nickname given to the first shot of the American Revolution. 6. Americans (and others) referred to British soldiers as Redcoats because of their brightly colored uniforms. 7. At the Second Continental Congress, colonial delegates voted to send the Olive Branch Petition to King George III and created an army led by George Washington. 8. The Continental Congress created the Continental Army to defend the colonies against British aggression. 9. George Washington took command of this army at the request of the Continental Congress. 10. The Continental Congress chose to send the Olive Branch Petition to King George III and Parliament, reiterating their desire for a peaceful resolution to the crisis. 11. Siege is a military term that means to surround a city or fortress with the goal of forcing the inhabitants to surrender due to a lack of supplies. 12. Benedict Arnold and Ethan Allan captured Fort Ticonderoga in New York, allowing George Washington to obtain much needed supplies and weapons. -

The American Revolution

The American Revolution The American Revolution Theme One: When hostilities began in 1775, the colonists were still fighting for their rights as English citizens within the empire, but in 1776 they declared their independence, based on a proclamation of universal, “self-evident” truths. Review! Long-Term Causes • French & Indian War; British replacement of Salutary Neglect with Parliamentary Sovereignty • Taxation policies (Grenville & Townshend Acts); • Conflicts (Boston Massacre & Tea Party, Intolerable Acts, Lexington & Concord) • Spark: Common Sense & Declaration of Independence Second Continental Congress (May, 1775) All 13 colonies were present -- Sought the redress of their grievances, NOT independence Philadelphia State House (Independence Hall) Most significant acts: 1. Agreed to wage war against Britain 2. Appointed George Washington as leader of the Continental Army Declaration of the Causes & Necessity of Taking up Arms, 1775 1. Drafted a 2nd set of grievances to the King & British People 2. Made measures to raise money and create an army & navy Olive Branch Petition -- Moderates in Congress, (e.g. John Dickinson) sought to prevent a full- scale war by pledging loyalty to the King but directly appealing to him to repeal the “Intolerable Acts.” Early American Victories A. Ticonderoga and Crown Point (May 1775) (Ethan Allen-Vt, Benedict Arnold-Ct B. Bunker Hill (June 1775) -- Seen as American victory; bloodiest battle of the war -- Britain abandoned Boston and focused on New York In response, King George declared the colonies in rebellion (in effect, a declaration of war) 1.18,000 Hessians were hired to support British forces in the war against the colonies. 2. Colonials were horrified Americans failed in their invasion of Canada (a successful failure-postponed British offensive) The Declaration of Independence A. -

American Self-Government: the First & Second Continental Congress

American Self-Government: The First and Second Continental Congress “…the eyes of the virtuous all over the earth are turned with anxiety on us, as the only depositories of the sacred fire of liberty, and…our falling into anarchy would decide forever the destinies of mankind, and seal the political heresy that man is incapable of self-government.” ~ Thomas Jefferson Overview Students will explore the movement of the colonies towards self-government by examining the choices made by the Second Continental Congress, noting how American delegates were influenced by philosophers such as John Locke. Students will participate in an activity in which they assume the role of a Congressional member in the year 1775 and devise a plan for America after the onset of war. This lesson can optionally end with a Socratic Seminar or translation activity on the Declaration of Independence. Grades Middle & High School Materials • “American Self Government – First & Second Continental Congress Power Point,” available in Carolina K- 12’s Database of K-12 Resources (in PDF format): https://k12database.unc.edu/wp- content/uploads/sites/31/2021/01/AmericanSelfGovtContCongressPPT.pdf o To view this PDF as a projectable presentation, save the file, click “View” in the top menu bar of the file, and select “Full Screen Mode” o To request an editable PPT version of this presentation, send a request to [email protected] • The Bostonians Paying the Excise Man, image attached or available in power point • The Battle of Lexington, image attached or available in power -

Was the American Revolution Avoidable? - Supporting Question 4

Was the American Revolution Avoidable? - Supporting Question 4 S.S. 4–I will explain what efforts were made to avoid war with the British before the American Revolution. - C3 STANDARD D2.HIS.16.6-8 4 3.5 3 2.5 2 1 0 The student will... Provide essential facts Provide important Provide basic and details from the facts and details vocabulary and source material and from the source simpler details to In addition to In addition to other sources to material to explain partially explain No level 3.0 level 2.0 With help, the comprehensively explain what efforts were what efforts were understanding performance, performance, student can what efforts were made made to avoid war made to avoid of very simple the student the student perform 2.0 to avoid war with the with the British war with the content or shows partial shows partial and 3.0 British before the before the British before the missing success at success at expectations. American Revolution American American evidence. level 4.0 level 3.0 and properly cited the Revolution and Revolution. sources. properly cited the sources. Supporting Question 4 What efforts were made to avoid war? Formative Performance Task Write a second claim supported by evidence for how efforts were made to avoid war. - cite your sources Featured Sources ❏ Background Information #1: What was the Olive Branch Petition? ❏ Background Information #2: Repeal of the Stamp Act ❏ Source A: Repeal of the Stamp Act ❏ Source B: Olive Branch Petition ❏ Source C: Excerpt from Plain Truth ❏ History Channel Source: Olive Branch Petition The fourth supporting question—“What efforts were made to avoid war?”—turns to the actions of people who worked to avoid war between Great Britain and the colonists. -

8Th US History Civil War and Reconstruction Units

8th US History Civil War and Reconstruction Units 1. Complete the first 4 weeks of work in order. The first week covers the Civil War. If you can answer the questions without completing all of the reading, you may do so, as you should have learned the majority of this content in class. Within the unit there are two video lessons, one about Harriet Tubman and another about the 54th Massachusetts. If you have access to your phone or the internet, watch the videos as they are assigned to complete the questions. 2. Weeks 2, 3, and 4 over lessons we have yet to cover in class, including about the period of time after the Civil War, called Reconstruction. You should use the textbook reading to complete the questions and assignments in this section. 3. Week 5 focuses on the STAAR practice unit. Please access the quizlet link on page 76, review the “US History at a glance” pages, and answer the practice problems using the “at a glance” information. 4. For online games, activities and extra practice check out: https://www.icivics.org/games 5. Khan Academy provides a free, online module for 8th Grade US History, including topic overviews and practice. Focus on The Civil War era (1844-1877) https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/us-history WEEK 1 The Civil War 21.1 Introduction he cannon shells bursting over Fort Sumter ended months of confu sion. The nation was at war. The time had come to choose sides. TFor most whites in the South, the choice was clear. -

The American Revolution: Political Upheaval Led to U.S. Independence by History.Com, Adapted by Newsela Staff on 05.12.17 Word Count 740 Level 800L

The American Revolution: Political Upheaval Led to U.S. Independence By History.com, adapted by Newsela staff on 05.12.17 Word Count 740 Level 800L Continental Army Commander-in-Chief George Washington leads his soldiers in the Battle of Princeton on January 3, 1777. Photo from Wikimedia The American Revolution was fought from 1775 to 1783. It is also known as the American Revolutionary War. In 1775, America was made up of 13 colonies, governed by the king in England. The people who lived there, known as colonists, thought the British government was unfair. Soon, fighting began between British troops and colonial rebels. By the following summer, the rebels had formed the Continental Army and were fighting a war for their independence. Trouble had been building France assisted the Continental Army. Together, they forced the British to surrender in 1781. Americans had won their independence by 1783. Well before that, by 1775, trouble had been building between colonists and the British authorities for more than 10 years. The British government tried to make more money off the colonies. They collected taxes on sugar, stamps, tea and other goods. This article is available at 5 reading levels at https://newsela.com. 1 This angered many colonists. They hated paying taxes to the British government while not being able to vote or govern themselves. They wanted the same rights as other British citizens. Declaration of rights In 1770, British soldiers shot and killed five colonists in Boston, Massachusetts. It was called the Boston Massacre. In December 1773, a band of Bostonians dressed up as Native Americans. -

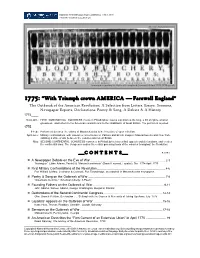

Colonists Respond to the Outbreak of War, 1774-1775, Compilation

MAKING THE REVOLUTION: AMERICA, 1763-1791 PRIMARY SOURCE COLLECTION American Antiquarian Society broadside reporting the Battle of Lexington & Concord,19 April 1775; 1775 (detail) 1775: “With Triumph crown AMERICA Farewell England” The Outbreak of the American Revolution: A Selection from Letters, Essays, Sermons, Newspaper Reports, Declarations, Poetry & Song, A Debate & A History 1774____* Sept.-Oct.: FIRST CONTINENTAL CONGRESS meets in Philadelphia; issues a petition to the king, a bill of rights, a list of grievances, and letters to the American colonists and to the inhabitants of Great Britain. The petition is rejected. 1775____ 9 Feb.: Parliament declares the colony of Massachusetts to be in a state of open rebellion. April-June: Military confrontations with casualties occur between Patriots and British troops in Massachusetts and New York, initiating a state of war between the colonies and Great Britain. May: SECOND CONTINENTAL CONGRESS convenes in Philadelphia, issues final appeals and declarations, and creates the continental army. The Congress remains the central governing body of the colonies throughout the Revolution. PAGES ___CONTENT S___ A Newspaper Debate on the Eve of War ............................................................................. 2-3 “Novanglus” (John Adams, Patriot) & “Massachusettensis” (Daniel Leonard, Loyalist), Dec. 1774-April 1775 First Military Confrontations of the Revolution...................................................................... 4-6 Fort William & Mary, Lexington & Concord, -

American Government: Chronology

At a Glance American Government: Chronology July 5, 1775- The Continental Congress September 14, 1786- The Annapolis sends the Olive Branch Petition to King Convention adjourns after calling for a George in the hopes of making peace. King convention to convene the following spring George rejects the petition. to amend the Articles of Confederation. July 4, 1776- The Continental Congress February 4, 1787- Shays’ Rebellion ends approves the Declaration of Independence. when the Massachusetts militia defeats Thomas Jefferson is the document’s primary Shays’ forces known as “Shaysites.” Shays author. and his men flee to Vermont. June 14, 1777- The Continental Congress February 21, 1787- Congress approves a adopts the stars and stripes as the national convention in Philadelphia to amend the flag. The flag will fly for the first time in Articles of Confederation. Maryland on September 3. May 3, 1787- James Madison arrives in November 15, 1777- The Continental Philadelphia early for Convention. Congress approves the Articles of Confederation. This establishes the United May 13, 1787- George Washington arrives States' first constitution. The Articles are for Convention. officially ratified in 1781. May 25, 1787- The Constitutional September 27, 1779- John Adams is Convention officially begins. selected to negotiate a peace treaty with Great Britain. May 29, 1787- Edmund Randolph presents the Virginia Plan for consideration (although March 1, 1781- The states officially ratify James Madison is the author). Charles the Articles of Confederation. Pinckney presents his plan for the new constitution. September 3, 1783- The Treaty of Paris officially ends the American Revolution and May 31, 1787- The delegates debate establishes the United States as a free and representation of the states in the new independent country. -

Exhibition Records, 1974-1976

Exhibition Records, 1974-1976 Finding aid prepared by Smithsonian Institution Archives Smithsonian Institution Archives Washington, D.C. Contact us at [email protected] Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Descriptive Entry.............................................................................................................. 1 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 1 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 2 Exhibition Records https://siarchives.si.edu/collections/siris_arc_251838 Collection Overview Repository: Smithsonian Institution Archives, Washington, D.C., [email protected] Title: Exhibition Records Identifier: Accession 99-106 Date: 1974-1976 Extent: 3.5 cu. ft. (3 record storage boxes) (1 document box) Creator:: National Portrait Gallery. Office of Exhibitions Language: English Administrative Information Prefered Citation Smithsonian Institution Archives, Accession 99-106, National Portrait Gallery. Office of Exhibitions, Exhibition Records Descriptive Entry This accession consists of exhibition records pertaining to The Dye is Now Cast: The Road to American Independence, an exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery (NPG) from -

Ms. Wiley's APUSH Period 3 Packet, 1754-1801 Name: Page #(S

Ms. Wiley’s APUSH Period 3 Packet, 1754-1801 Name: Page #(s) Document Name 2-5 1) Period 3 Summary: ?s, Concepts, Themes, & Assessment Info 6 2) Textbook Assignment (Outline Guidelines) 7-10 3) Timeline 11-13 4) French & Indian War Overview (1754-1763) 14-15 5) ‘Reluctant Revolutionaries’ Documentary 16-23 6) Primary Sources from the Revolutionary Period 24-25 7) HBO Episode on Independence 26-28 8) Secondary Sources from the Revolutionary Period 29-32 9) Examining the Electoral College 33-38 10) The Washington Administration (1789-1797) 39-42 11) The Adams Administration (1797-1801) 43-44 12) HBO Episode on Adams’ Presidency 1 Period 3 Summary (1754-1800) Key Questions for Period 3: - For what reasons did the colonists shift from being loyal British subjects in 1770 to revolutionaries by 1776? How reluctant or enthusiastic was the average colonist towards the war effort? - To what extent should Britain’s behavior in the 1760s/’70s towards its American colonies be characterized as “tyrannical”? - How “revolutionary” was the Revolution? To what extent did politics, economics, and society change in its aftermath? (short and long-term) - What political philosophies undergird the founding documents of the U.S.? To what extent was the government, created by the Constitution in 1787, “democratic” in nature? - How were masculinity and femininity defined in the new republic? - To what extent did the Founders and first leaders of the republic agree on how the federal government should operate? To what extent did they agree on how the Constitution should be interpreted? - For what reasons did political parties emerge in the U.S.? Do the parties of today resemble the original two parties in any ways? - How did slavery play a role in politics, economics, and society in the early republic? - How did the new republic engage Native Americans and other nations? Key Concept 1: British imperial attempts to assert tighter control over its North American colonies and the colonial resolve to pursue self- government led to a colonial independence movement and the Revolutionary War. -

The American Revolution: Political Upheaval Led to U.S. Independence by History.Com, Adapted by Newsela Staff on 05.12.17 Word Count 964 Level 1090L

The American Revolution: Political Upheaval Led to U.S. Independence By History.com, adapted by Newsela staff on 05.12.17 Word Count 964 Level 1090L Continental Army Commander-in-Chief George Washington leads his soldiers in the Battle of Princeton on January 3, 1777. Photo from Wikimedia The American Revolution (1775 to 1783) is also known as the American Revolutionary War. The conflict arose from growing tensions between residents of Britain's 13 American colonies and the British colonial government. The British king ruled over the colonies from across the Atlantic, in England. In April 1775, fighting began between British troops and colonial rebels, also known as colonists. By the following summer, the rebels were fighting a war for their independence. Assistance from France helped the Continental Army force the British to surrender in 1781. Americans had won their independence, though fighting would not end until 1783. Tensions, resentment and violence By 1775, tensions had been building between colonists and the British authorities for more than a decade. The British government had been trying to make more money off the colonies. They collected taxes on sugar, stamps, tea and other goods. This was met with anger by many colonists, This article is available at 5 reading levels at https://newsela.com. who resented being taxed, but had no representatives in British government. They demanded the same rights as other British citizens. Violence erupted in 1770, when British soldiers shot and killed five colonists in Boston, Massachusetts. It became known as the Boston Massacre. In December 1773, a band of Bostonians dressed as Native Americans boarded British ships and dumped 342 chests of tea into Boston Harbor.