Viewshafts and Height Sensitive Areas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Appendix 4 Mana Whenua

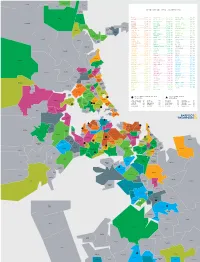

The Proposed Auckland Unitary Plan (notified 30 September 2013) Proposed track changes for council’s closing statement 22 July 2015 Sites highlighted green are recommended to be amendend to reflect accurate location on schedule and maps Sites highlighted orange are recommended to be deleted because location is not confirmed Sites highlighted grey are recommended to be deleted because Mana Whenua have not assigned values Sites highlighted red are recommended to be deleted because they are non-Māori or duplicates Sites highlighted blue are recommended to be deleted because unknown whether natural feature or archaeological PART 5 • APPENDICES» Appendix 4 Mana Whenua Appendix 4.2 Schedule of Ssites and places of value to Mana Whenua [all provisions in this appendix are: rcp/dp] NZAA Site Values ID CHI Number Location Te Haruhi Bay | Shakespear Regional Park | abcef ID 1 87 R10_699 Whangaparaoa Peninsula | Hauraki Gulf. Whangaparapara | Aotea Island | Great Barrier ID 2 502 S09_116 Island. | Hauraki Gulf | Auckland City Bluebell Point | Tawharanui Regional Park | bc ID 3 829 R09_235 Hauraki Gulf | Rodney | Auckland ID 4 1066 Q11_412 abcdef Parawai | Te Henga | Bethells Beach Rangiriri Creek | Capes Road | Pollok | Awhitu abcdef ID 5 1752 R12_799 Peninsula | Manukau Harbour ID 6 3832 R11_581 bc Papahinu | Pukaki Creek | Papatoetoe ID 7 3835 R11_591 bc Waokauri Creek | Pukaki Creek | Papatoetoe ID 8 3843 R11_599 abc Waokauri Creek | Papatoetoe ID 9 3845 R11_601 bc Waokauri Creek | Papatoetoe ID 10 3846 R11_603 bc Waokauri Creek | Papatoetoe -

Schedule 6 Outstanding Natural Features Overlay Schedule

Schedule 6 Outstanding Natural Features Overlay Schedule Schedule 6 Outstanding Natural Features Overlay Schedule [rcp/dp] Introduction The factors in B4.2.2(4) have been used to determine the features included in Schedule 6 Outstanding Natural Features Overlay Schedule, and will be used to assess proposed future additions to the schedule. ID Name Location Site type Description Unitary Plan criteria 2 Algies Beach Algies Bay E This site is one of the a, b, g melange best examples of an exposure of the contact between Northland Allocthon and Miocene Waitemata Group rocks. 3 Ambury Road Mangere F A complex 140m long a, b, c, lava cave Bridge lava cave with two d, g, i branches and many well- preserved flow features. Part of the cave contains unusual lava stalagmites with corresponding stalactites above. 4 Anawhata Waitākere A This locality includes a a, c, e, gorge and combination of g, i, l beach unmodified landforms, produced by the dynamic geomorphic processes of the Waitakere coast. Anawhata Beach is an exposed sandy beach, accumulated between dramatic rocky headlands. Inland from the beach, the Anawhata Stream has incised a deep gorge into the surrounding conglomerate rock. 5 Anawhata Waitākere E A well-exposed, and a, b, g, l intrusion unusual mushroom-shaped andesite intrusion in sea cliffs in a small embayment around rocks at the north side of Anawhata Beach. 6 Arataki Titirangi E The best and most easily a, c, l volcanic accessible exposure in breccia and the eastern Waitākere sandstone Ranges illustrating the interfingering nature of Auckland Unitary Plan Operative in part 1 Schedule 6 Outstanding Natural Features Overlay Schedule the coarse volcanic breccias from the Waitākere Volcano with the volcanic-poor Waitematā Basin sandstone and siltstones. -

Auckland / Matamata / Rotorua

PCM: SD15 SOUTHERN CROSS Pacific Destinations Ltd 1 Boundary Rd, Hobsonville Auckland, New Zealand Email: [email protected] Telephone: +64 9 915-8888 Facsimile: +64 9 915-8889 www.pacificdestinations.co.nz Quotation: SD15 SOUTHERN CROSS 21-22 Day 1: Arrive Auckland On arrival to Auckland Airport please make your way to the Budget Rental Car counter located within the arrivals hall to collect your Budget rental car and make your way to your accommodation. AUCKLAND - an exciting, sporting and cultural city, sprawled on a narrow isthmus, between two harbours. The Waitemata and Manukau Harbours, are a main feature of the city, along with numerous volcanic cones such as Mount Eden and Rangitoto Island. The city's many beaches, marinas and parks, make it ideal for outdoor pursuits such as yachting, rugby, cricket or a day at the beach. The Auckland metropolitan area is New Zealand's biggest city, and the population mix of European, Maori, and Pacific Islander, make Auckland the largest Polynesian city in the World. Day 2: Auckland Skytower – Sky Deck Admission Admission is included to both sky deck and the main observation deck of Sky Tower. Auckland War Memorial Museum Auckland War Memorial Museum where exciting stories of the Pacific, New Zealand’s people, and the flora and fauna and landforms of our unique islands, are told within a memorial dedicated to those who have sacrificed their lives for our country. In one of New Zealand's most outstanding historical buildings, boldly situated in the Domain - a central city pleasure garden - you encounter exhibitions that will excite you with the artistic legacy and cultures of the peoples of the Pacific; the monumental carvings, buildings, canoes and taonga (treasures) of the Maori; and the diversity of cultures which now combine to form the rich tapestry of race, nationality and creed which is modern New Zealand. -

TOP MEDIAN SALE PRICE (OCT19—SEP20) Hatfields Beach

Warkworth Makarau Waiwera Puhoi TOP MEDIAN SALE PRICE (OCT19—SEP20) Hatfields Beach Wainui EPSOM .............. $1,791,000 HILLSBOROUGH ....... $1,100,000 WATTLE DOWNS ......... $856,750 Orewa PONSONBY ........... $1,775,000 ONE TREE HILL ...... $1,100,000 WARKWORTH ............ $852,500 REMUERA ............ $1,730,000 BLOCKHOUSE BAY ..... $1,097,250 BAYVIEW .............. $850,000 Kaukapakapa GLENDOWIE .......... $1,700,000 GLEN INNES ......... $1,082,500 TE ATATŪ SOUTH ....... $850,000 WESTMERE ........... $1,700,000 EAST TĀMAKI ........ $1,080,000 UNSWORTH HEIGHTS ..... $850,000 Red Beach Army Bay PINEHILL ........... $1,694,000 LYNFIELD ........... $1,050,000 TITIRANGI ............ $843,000 KOHIMARAMA ......... $1,645,500 OREWA .............. $1,050,000 MOUNT WELLINGTON ..... $830,000 Tindalls Silverdale Beach SAINT HELIERS ...... $1,640,000 BIRKENHEAD ......... $1,045,500 HENDERSON ............ $828,000 Gulf Harbour DEVONPORT .......... $1,575,000 WAINUI ............. $1,030,000 BIRKDALE ............. $823,694 Matakatia GREY LYNN .......... $1,492,000 MOUNT ROSKILL ...... $1,015,000 STANMORE BAY ......... $817,500 Stanmore Bay MISSION BAY ........ $1,455,000 PAKURANGA .......... $1,010,000 PAPATOETOE ........... $815,000 Manly SCHNAPPER ROCK ..... $1,453,100 TORBAY ............. $1,001,000 MASSEY ............... $795,000 Waitoki Wade HAURAKI ............ $1,450,000 BOTANY DOWNS ....... $1,000,000 CONIFER GROVE ........ $783,500 Stillwater Heads Arkles MAIRANGI BAY ....... $1,450,000 KARAKA ............. $1,000,000 ALBANY ............... $782,000 Bay POINT CHEVALIER .... $1,450,000 OTEHA .............. $1,000,000 GLENDENE ............. $780,000 GREENLANE .......... $1,429,000 ONEHUNGA ............. $999,000 NEW LYNN ............. $780,000 Okura Bush GREENHITHE ......... $1,425,000 PAKURANGA HEIGHTS .... $985,350 TAKANINI ............. $780,000 SANDRINGHAM ........ $1,385,000 HELENSVILLE .......... $985,000 GULF HARBOUR ......... $778,000 TAKAPUNA ........... $1,356,000 SUNNYNOOK ............ $978,000 MĀNGERE ............. -

Pukekawa — the Domain Volcano

Pukekawa — the Domain Volcano New Zealand is a land of volcanoes The springs provided Auckland’s first leading the Ngapuhi from the North and earthquakes. Volcanic activity has piped water supply in 1866. The and Potatau Te Wherowhero leading played a major role in shaping New Domain Wintergarden’s fernery occu- the local Ngati Whatua. A sacred Zealand since its earliest origins, pies a disused scoria quarry on the Totara tree planted by Princess Te around 500 million years ago. north side of the small central scoria Puea Herangi to commemorate the Auckland City is built on an active field cone. battles and the eventual settlement of of small basalt volcanoes. Forty-eight the dispute stands on Pukekaroa sur- have erupted within 29km of the city Maori Use of Pukekawa rounded by a palisade. centre over the last 150 000 years. The The Domain has been altered signifi- Later Use of Auckland’s most recent eruption, 600 years ago, cantly by contact with humans. When Volcanoes formed Rangitoto Island at the en- Maori people arrived in Auckland they trance to Auckland Harbour. Because cleared the land for gardens, particu- Pukekawa was part of the land which of the intensity of past volcanic and larly choosing the fertile north-facing Ngati Whatua sold to the Europeans geologic activity within the Auckland who by 1860 had drained and filled region another eruption possible. slopes of the volcanic cones. Later their descendants looked to more per- the swamp and turned it into cricket Auckland Domain Volcano manent settlements, so that parts of fields. -

Hidden Eruptions

HIDDEN ERUPTIONS The Search for AUCKLAND’S VOLCANIC PAST FACT SHEET 02 Fun volcanic facts from the DEtermining VOlcanic Risk in Auckland (DEVORA) Project The Auckland region has a long history of being affected by volcanic eruptions. The region has experienced at least 53 eruptions from the Auckland Volcanic Field (AVF) in the past 200,000 years, and it has been covered by ash from central North Island volcanoes at least 300 times during that period. To determine exactly how often the Auckland region has been affected by eruptions, scientists study ash layers that have been preserved in lake beds. They now think that ash has How can we tell where fallen on Auckland at least once every 600 years! ash layers come from? Scientists have drilled 7 lakes and dried-up lakes looking for ash: Colour /Te Kopua Kai a Hiku, Panmure Basin A white layer = Ash from a larger, more , Pukaki Lagoon, What is volcanic ash? Lake Pupuke /Whakamuhu, distant volcano (e.g. Taupo). Ōrākei Basin, Glover Park When volcanoes erupt, they eject small fragments /Te Hopua a Rangi, and Gloucester Park A black layer = Ash from a smaller, local of broken rock and lava into the air. This material /Te Kopua o Matakerepō. Auckland volcano (e.g. Mt. Wellington). is called tephra. Tephra less than 2mm in size is Onepoto Basin called ash. Ash is so small and light that it is easily picked up and carried by the wind. Ash can travel Location in the core hundreds of kilometres before settling out of the Some large-scale volcanic eruptions are ash cloud and falling to the ground. -

Auckland Trail Notes Contents

22 October 2020 Auckland trail notes Contents • Mangawhai to Pakiri • Mt Tamahunga (Te Hikoi O Te Kiri) Track • Govan Wilson to Puhoi Valley • Puhoi Track • Puhoi to Wenderholm by kayak • Puhoi to Wenderholm by walk • Wenderholm to Stillwater • Okura to Long Bay • North Shore Coastal Walk • Coast to Coast Walkway • Onehunga to Puhinui • Puhinui Stream Track • Totara Park to Mangatawhiri River • Hunua Ranges • Mangatawhiri to Mercer Mangawhai to Pakiri Route From Mangawhai Heads carpark, follow the road to the walkway by 44 Wintle Street which leads down to the estuary. Follow the estuary past a camping ground, a boat ramp & holiday baches until wooden steps lead up to the Findlay Street walkway. From Findlay Street, head left into Molesworth Drive until reaching Mangawhai Village. Then a right into Moir Street, left into Insley Street and across the estuary then left into Black Swamp Road. Follow this road until reaching Pacific Road which leads you through a forestry block to the beach and the next stage of Te Araroa. Bypass Note: You could obtain a boat ride across the estuary to the Mangawhai Spit to avoid the road walking section. Care of sand-nesting birds is required on this Scientific Wildlife Reserve - please stick to the shoreline. Just 1km south, a stream cuts across the beach and it can go over thigh height, as can other water crossings on this track. Follow the coast southwards for another 2km, then take the 1 track over Te Ārai Point. Once back on the beach, continue south for 12km (fording Poutawa Stream on the way) until you cross the Pākiri River then head inland to reach the end of Pākiri River Road. -

Auckland Plan Targets: Monitoring Report 2015 with DATA for the SOUTHERN INITIATIVE AREA

Auckland plan targets: monitoring report 2015 WITH DATA FOR THE SOUTHERN INITIATIVE AREA Auckland Plan Targets: Monitoring Report 2015 With Data for the Southern Initiative Area March 2016 Technical Report 2016/007 Auckland Council Technical Report 2016/007 ISSN 2230-4525 (Print) ISSN 2230-4533 (Online) ISBN 978-0-9941350-0-1 (Print) ISBN 978-0-9941350-1-8 (PDF) This report has been peer reviewed by the Peer Review Panel. Submitted for review on 26 February 2016 Review completed on 18 March 2016 Reviewed by one reviewer. Approved for Auckland Council publication by: Name: Dr Lucy Baragwanath Position: Manager, Research and Evaluation Unit Date: 18 March 2016 Recommended citation Wilson, R., Reid, A and Bishop, C (2016). Auckland Plan targets: monitoring report 2015 with data for the Southern Initiative area. Auckland Council technical report, TR2016/007 Note This technical report updates and replaces Auckland Council technical report TR2015/030 Auckland Plan Targets: monitoring report 2015 which does not contain data for the Southern Initiative area. © 2016 Auckland Council This publication is provided strictly subject to Auckland Council's copyright and other intellectual property rights (if any) in the publication. Users of the publication may only access, reproduce and use the publication, in a secure digital medium or hard copy, for responsible genuine non-commercial purposes relating to personal, public service or educational purposes, provided that the publication is only ever accurately reproduced and proper attribution of its source, publication date and authorship is attached to any use or reproduction. This publication must not be used in any way for any commercial purpose without the prior written consent of Auckland Council. -

Coastal Map Series 3

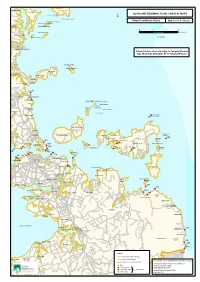

HEPBURN CREEK KAWAU ISLAND ALGIES BAY BEEHIVE ISLAND CHALLENGER ISLAND MOTUKETEKETE ISLAND MOTUREKAREKA ISLAND PUKAPUKA MOTUTARA ISLAND MOTUORA ISLAND MAHURANGI WEST 1 TE HAUPA ISLAND WENDERHOLM WAIWERA MAHURANGI IS OREWA WOODED ISLAND TIRITIRI MATANGI ISLAND REGIONAL PARK SILVERDALE MATAKATIA BAY BIG MANLY ARKLES BAY STILLWATER WADE HEADS 21 LONG BAY OKURA MARINE RESERVE LONG BAY REGIONAL PARK MOTUHOROPAPA ISLAND THE NOISES TORBAY DAVID ROCKS OTATA ISLAND RAKINO IS. ZENO ROCK BROWNS BAY MARIA ISLAND ALBANY THE NOISES HORUHORU ROCK MURRAYS BAY 173(Gannet Rock) MAIRANGI BAY MOTUTAPU ISLAND MILFORD TARAHIKI IS TAKAPUNA RANGITOTO ISLAND ONEROA PALM BEACH (Shag Is) BEACH HAVEN BLACKPOOL 115 SURFDALE ONETANGI PAKATOA ISLAND 167 OSTENDWAIHEKE ISLAND 94 WAIHEKE ISLAND NORTHCOTE 168 FRENCHMANS CAP DOMAIN BAYSWATER MOTUIHE IS. 169 42 PAPAKOHATU IS 89OMIHA ROTOROA (Crusoe Is) 106 ISLAND 41 DEVONPORTHEAD 170 46 64 BROWNS IS. 172 (Motukorea) 44 HERNE BAY 66 KOHIMARAMA 172 ST HELIERS AUCKLAND ORAKEI PT. CHEVALIER DOMAIN GLENDOWIE TAHUNA BEACH WATERVIEW GLEN INNES PONUI ISLAND REMUERA 74 MOTUKARAKA IS (Chamberlins Is) PARKMARAETAI BEACHLANDS FARM COVE PANMURE HOWICK PANMURE BASIN BEACHLANDS PAKIHI ISLAND MT WELLINGTON DUDER PARK 126 PAKURANGA ONEHUNGA BLOCKHOUSE BAY 130 176 NIMT AMBURY REGIONAL PARK 174 OTAHUHU EAST TAMAKI WHITFORD 175 REGIONAL MANGERE SEWAGE PARK KAWAKAWA BAY PUKETUTU ISLAND MANGERE ORERE POINT ORERE TAPAPAKANGA REGIONAL PARK CLEVEDON PUHINUI MATINGARAHI WIROA IS. MANUREWA MANUKAU HARBOUR WEYMOUTH TAKANINI WAHARAU 177 WATTLE DOWNSCONIFER GROVE REGIONAL PARK PAPAKURA WHAREKAWA HUNUA RANGES REGIONAL PARK 178 ELLETS BEACH SEAGROVE 179 KARAKA 180 DRURY KAIAUA KINGSEAT CLARKS BEACH WAIAU PA GLENBROOK BEACH. -

The New Zealand Gazette 1239

4 AUGUST THE NEW ZEALAND GAZETTE 1239 In Bankruptcy-In the Supreme Court Holden at Auckland Reed, Phyllis Ethel, Kingsland, Auckland, Machine Press Operator. Re~an, Lionel William, Grafton, Auckland, Contractor. Reid, Robert Bruce, Epsom, Auckland, Builder. 'NOTICE is hereby given that statements of accounts and Reilly, Richard Charles Arthur, Northcote, Bus Driver. balance sheets in respect of the undermentioned estates, Rhind, Earl Raymond, Epsom, Auckland, Baker. together with the reports of the Audit Office thereon. have been Rix, Edward vYalker, Auckland, Labourer. duly filed in the above Court; and I hereby further 'give notice Roberts, vV. A., Mount Eden, Auckland, Builder. that at the sittings of the said Court to be holden on Friday Ross, S. vV., New Lynn, Panelbeater. the 26th day of August 1955, at 10 o )clock in the forenooi{ Rowan, Albert Allen, Epsom, Auckland, Horse Trainer. or as soon thereafter as application may be heard, I intend Rowe, Arthur Charles, Avondale, Auckland, Builder. to apply for orders releasing me from. the administration of Sandison, W., Papakura, Drainlayer. the said estates. Sayes, Edwin, Auckland, Printer. Scaife, Jack Garnet, Remuera, Carpenter. Adams, Dennis, Thames, Driver. Schiavi, Alan Vvilliam, Auckland, Electrician. Albury, Gordon, Titirangi, Builder and Contractor. Scott, R. A., Auckland, Plumber. Arnold, Albert Colin, formerly of Taupo, but now of Auck Shenton, A. J., Auckland, Jewellery Dealer. land, Building Contractor. Short, George Francis, Mount Eden, Motor Mechanic. Askew,. Ian James vVemyss, Kingsland, Auckland, Motor Stevens, Bryan Howard, Auckland, Tram.wayman. Engmeer. Stewart, Raymond vVarren, Auckland, Truck Driver. Atkins, Peter Paul Joseph, Devonport, Reporter. Stoddart, James Mervyn, Mount Eden, Auckland, Salesman. -

Towards Characterising Rhyolitic Tephra Layers from New

Aberystwyth University Towards characterising rhyolitic tephra layers from New Zealand with rapid, non-destructive -XRF core scanning Peti, Leonie; Augustinus, Paul C.; Gadd, Patricia S.; Davies, Sarah Published in: Quaternary International DOI: 10.1016/j.quaint.2018.06.039 Publication date: 2019 Citation for published version (APA): Peti, L., Augustinus, P. C., Gadd, P. S., & Davies, S. (2019). Towards characterising rhyolitic tephra layers from New Zealand with rapid, non-destructive -XRF core scanning. Quaternary International, 514, 161-172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2018.06.039 General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the Aberystwyth Research Portal (the Institutional Repository) are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the Aberystwyth Research Portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the Aberystwyth Research Portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. tel: +44 1970 62 2400 email: [email protected] Download date: 11. Oct. 2021 Accepted Manuscript Towards characterising rhyolitic tephra layers from New Zealand with rapid, non- destructive μ-XRF core scanning Leonie Peti, Paul C. Augustinus, Patricia S. -

Dilemma of Geoconservation of Monogenetic Volcanic Sites Under Fast Urbanization and Infrastructure Developments with Special Re

sustainability Article Dilemma of Geoconservation of Monogenetic Volcanic Sites under Fast Urbanization and Infrastructure Developments with Special Relevance to the Auckland Volcanic Field, New Zealand Károly Németh 1,2,3,* , Ilmars Gravis 3 and Boglárka Németh 1 1 School of Agriculture and Environment, Massey University, Palmerston North 4442, New Zealand; [email protected] 2 Institute of Earth Physics and Space Science, 9400 Sopron, Hungary 3 The Geoconservation Trust Aotearoa, 52 Hukutaia Road, Op¯ otiki¯ 3122, New Zealand; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +64-27-4791484 Abstract: Geoheritage is an important aspect in developing workable strategies for natural hazard resilience. This is reflected in the UNESCO IGCP Project (# 692. Geoheritage for Geohazard Resilience) that continues to successfully develop global awareness of the multifaced aspects of geoheritage research. Geohazards form a great variety of natural phenomena that should be properly identified, and their importance communicated to all levels of society. This is especially the case in urban areas such as Auckland. The largest socio-economic urban center in New Zealand, Auckland faces potential volcanic hazards as it sits on an active Quaternary monogenetic volcanic field. Individual volcanic geosites of young eruptive products are considered to form the foundation of community Citation: Németh, K.; Gravis, I.; outreach demonstrating causes and consequences of volcanism associated volcanism. However, in Németh, B. Dilemma of recent decades, rapid urban development has increased demand for raw materials and encroached Geoconservation of Monogenetic on natural sites which would be ideal for such outreach. The dramatic loss of volcanic geoheritage Volcanic Sites under Fast of Auckland is alarming.