Ithaca College Symphony Orchestra Octavio Más-Arocas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jazz Concert

Artist Series presents Sonatas for Violin and Piano featuring Maria Sampen, violin and Oksana Ezhokina, piano Saturday, November 14, 2015 at 3 pm Lagerquist Concert Hall, Mary Baker Russell Music Center Pacific Lutheran University School of Arts and Communication / Department of Music presents: Artist Series Sonatas for Violin and Piano Maria Sampen, violin Oksana Ezhokina, piano Saturday, November 14, 2015, at 3 pm Lagerquist Concert Hall, Mary Baker Russell Music Center Welcome to Lagerquist Concert Hall. Please disable the audible signal on all watches, pagers and cellular phones for the duration of the concert. Use of cameras, recording equipment and all digital devices is not permitted in the concert hall. PROGRAM Scherzo in C Minor for Violin and Piano, WoO 2 ............................................ Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) Sonata for Violin and Piano in A Major, Op. 100 ................................................................. Johannes Brahms Allegro amabile Andante tranquillo – Vivace Allegretto grazioso INTERMISSION Sonata No. 3 for Violin and Piano in A Minor, Op. 25 .......................................... George Enescu (1881-1955) Moderato malinconico Andante sostenuto e misterioso Allegro con brio, ma non troppo mosso About the Artists Russian-born pianist Oksana Ezhokina appears frequently as guest recitalist and chamber musician on concert series across the United States and abroad. She has soloed with the Seattle Symphony, St. Petersburg Chamber Philharmonic and Tacoma Symphony, and performed in venues such as the Phillips Collection in Washington DC, Benaroya Hall in Seattle, Governor’s Mansion in Olympia, Davies Orchestra Hall in San Francisco, and Klassik Keyifler Festival in Turkey. A dedicated performer of new music, she has premiered works by Marilyn Shrude, Wayne Horvitz, Bern Herbolsheimer, and Laura Kaminsky, among others. -

2015-10-23 Monteverdi Vespers

welcome pacific musicworks ensemble I will never forget the first Stephen Stubbs time I participated in a full music director & lute performance of the Monteverdi Joseph Adam Vespers. It was one of a handful organ of pivotal moments in my life Maxine Eilander so far when I felt that I was harp not really in control of my own Tekla Cunningham & Linda Melsted destiny. It might sound like violins hyperbole, but my experience Laurie Wells & Romeric Pokorny is that this is a work of such violas persuasive power, architectural Photo credit Jan Gates brilliance and raw beauty, that it literally changed the course William Skeen cello of my life. Christopher Jackson was the conductor of the Studio de Musique Ancienne de Montréal on that occasion Moriah Neils and I remember the joy, fascination and pure enthusiasm he bass managed to communicate to everyone involved. I was totally Bruce Dickey & Kiri Tollaksen hooked and felt so compelled and intrigued with how this cornettos work made me feel, that 25 years later, I am still spending Greg Ingles, Erik Schmalz and Mack Ramsey my time convincing anybody who will listen, that there is no sackbuts music that will make them feel luckier to be alive. Christopher Jackson died on September 25th, 2015, after a long and extremely influential career as a master of renaissance and baroque music. His inspirational work with the SMAM and as Dean of the Faculty of Arts at Concordia brought him into regular contact with hundreds of young and vancouver chamber choir aspiring musicians over the years. I will be forever grateful to him for first introducing me and many others to this wondrous music, as well as for instilling in me a desire to perform and promote art that still has the amazing power to transform lives over 400 years later. -

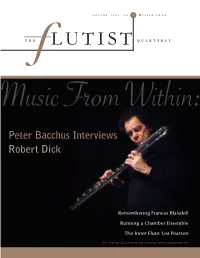

The Flutist Quarterly Volume Xxxv, N O

VOLUME XXXV , NO . 2 W INTER 2010 THE LUTI ST QUARTERLY Music From Within: Peter Bacchus Interviews Robert Dick Remembering Frances Blaisdell Running a Chamber Ensemble The Inner Flute: Lea Pearson THE OFFICIAL MAGAZINE OF THE NATIONAL FLUTE ASSOCIATION , INC :ME:G>:C8: I=: 7DA9 C:L =:69?D>CI ;GDB E:6GA 6 8ji 6WdkZ i]Z GZhi### I]Z cZl 8Vadg ^h EZVgaÉh bdhi gZhedch^kZ VcY ÓZm^WaZ ]ZVY_d^ci ZkZg XgZViZY# Djg XgV[ihbZc ^c ?VeVc ]VkZ YZh^\cZY V eZg[ZXi WaZcY d[ edlZg[ja idcZ! Z[[dgiaZhh Vgi^XjaVi^dc VcY ZmXZei^dcVa YncVb^X gVc\Z ^c dcZ ]ZVY_d^ci i]Vi ^h h^bean V _dn id eaVn# LZ ^ck^iZ ndj id ign EZVgaÉh cZl 8Vadg ]ZVY_d^ci VcY ZmeZg^ZcXZ V cZl aZkZa d[ jcbViX]ZY eZg[dgbVcXZ# EZVga 8dgedgVi^dc *). BZigdeaZm 9g^kZ CVh]k^aaZ! IC (,'&& -%%".),"(',* l l l # e Z V g a [ a j i Z h # X d b Table of CONTENTS THE FLUTIST QUARTERLY VOLUME XXXV, N O. 2 W INTER 2010 DEPARTMENTS 5 From the Chair 51 Notes from Around the World 7 From the Editor 53 From the Program Chair 10 High Notes 54 New Products 56 Reviews 14 Flute Shots 64 NFA Office, Coordinators, 39 The Inner Flute Committee Chairs 47 Across the Miles 66 Index of Advertisers 16 FEATURES 16 Music From Within: An Interview with Robert Dick by Peter Bacchus This year the composer/musician/teacher celebrates his 60th birthday. Here he discusses his training and the nature of pedagogy and improvisation with composer and flutist Peter Bacchus. -

Proceedings of the Istanbul Spectral Music Conference

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Research Commons@Waikato founding, this globally established Publications festival’s mission remains the same— we are steadfastly dedicated to the pursuit of the curiosity that is so Robert Reigle and Paul Whitehead deeply rooted in humankind’s nature, (Editors): Spectral World Musics: and we continue to peer intrepidly far Proceedings of the Istanbul into the future. Our immediate objec- Spectral Music Conference tive: to once again foment a fruitful, fascinating dialog at the interface of Softcover, two CD-Audio discs, 2008, art, technology and society.” This is a ISBN 978-9944-396-27-1, 457 pages; praiseworthy mission statement. But Pan Yayıncılık, Barbaros Bulvarı, Ars Electronica’s intrepid peering into 18/4 Bes¸iktas¸ 3435 Istanbul,˙ Turkey; the future with Armageddon exhibits telephone (+90) 212-2275675; fax may have thwarted for the moment (+90) 212-2275674; electronic mail its immediate objective of fomenting [email protected]; dialog. The current reviewers were Web pankitap.com/. sometimes left at a nonplus. And Mr. Fontana’s prize-winning work, Reviewed by Ian Whalley understood as the focal sound state- Hamilton, New Zealand ment of the 2009 festival, suggests that music, for the time being, has This collection is an outcome of not yet recovered from its speech- the Spectral Musics Conference held lessness and articulated a response. at Istanbul˙ Technical University, Or, perhaps its response is to recoil 18–23 November 2003, organized primarily extracts rather than full and to recollect the harmony of the by Michael Ellison, Robert Reigle, works. -

Guest Ensemble Recital: the Mellits Consort

Ithaca College Digital Commons @ IC All Concert & Recital Programs Concert & Recital Programs 9-17-2016 Guest Ensemble Recital: The elM lits Consort The elM lits Consort Kevin Gallagher Danny Tunick Christina Buciu Elizabeth Simkin See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation The eM llits Consort; Gallagher, Kevin; Tunick, Danny; Buciu, Christina; Simkin, Elizabeth; and Mellits, Marc, "Guest Ensemble Recital: The eM llits Consort" (2016). All Concert & Recital Programs. 2104. http://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs/2104 This Program is brought to you for free and open access by the Concert & Recital Programs at Digital Commons @ IC. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Concert & Recital Programs by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ IC. Authors The eM llits Consort, Kevin Gallagher, Danny Tunick, Christina Buciu, Elizabeth Simkin, and Marc Mellits This program is available at Digital Commons @ IC: http://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs/2104 The Mellits Consort Kevin Gallagher, electric guitar Danny Tunick, amplified marimba Cristina Buciu, amplified violin Elizabeth Simkin, amplified cello Marc Mellits, keyboard Hockett Family Recital Hall Saturday, September 17th, 2016 8:15 pm Program Opening Marc Mellits (b. 1966) Broken Glass Mellits paranoid cheese Mellits The Misadventures of Soup Mellits Lefty's Elegy Mellits Machine IV Mellits Intermission Srećan Rođendan, Marija! Mellits Troica Mellits Mara's Lullaby Mellits Dreadlocked Mellits Machine III Mellits Machine V Mellits The Mellits Consort The Mellits Consort is an ensemble devoted to the music of Marc Mellits. It is an amplified group consisting of amplified Violin, amplified Cello, Electric Guitar, amplified Marimba, and Keyboard. -

THIRD COAST PERCUSSION with Notre Dame Vocale, Carmen-Helena Téllez, Director PRESENTING SERIES TEDDY EBERSOL PERFORMANCE SERIES SUN, JAN 26 at 2 P.M

THIRD COAST PERCUSSION with Notre Dame Vocale, Carmen-Helena Téllez, director PRESENTING SERIES TEDDY EBERSOL PERFORMANCE SERIES SUN, JAN 26 AT 2 P.M. LEIGHTON CONCERT HALL DeBartolo Performing Arts Center University of Notre Dame Notre Dame, Indiana AUSTERITY MEASURES Concert Program Mark Applebaum (b. 1967) Wristwatch: Geology (2005) (5’) Marc Mellits (b. 1966) Gravity (2012) (11’) Thierry De Mey (b. 1956) Musique de Tables (1987) (8’) Steve Reich (b. 1936) Proverb (1995) (14’) INTERMISSION Timo Andres (b. 1985) Austerity Measures (2014) (25’) Austerity Measures was commissioned by the University of Notre Dame’s DeBartolo Performing Arts Center and Sidney K. Robinson. This commission made possible by the Teddy Ebersol Endowment for Excellence in the Performing Arts. This engagement is supported by the Arts Midwest Touring Fund, a program of Arts Midwest, which is generously supported by the National Endowment for the Arts with additional contributions from the Indiana Arts Commission. PERFORMINGARTS.ND.EDU Find us on PROGRAM NOTES: Mark Applebaum is a composer, performer, improviser, electro-acoustic instrument builder, jazz pianist, and Associate Professor of Composition and Theory at Stanford University. In his TED Talk, “Mark Applebaum, the Mad Scientist of Music,” he describes how his boredom with every familiar aspect of music has driven him to evolve as an artist, re-imagining the act of performing one element at a time, and disregarding the question, “is it music?” in favor of “is it interesting?” Wristwatch: Geology is scored for any number of people striking rocks together. The “musical score” that tells the performs what to play is a watch face with triangles, squares, circles and squiggles. -

Orchestra Personnel

FROM SUFFRAGE TO STONEWALL 2019 DAVID ALAN MILLER HEINRICH MEDICUS MUSIC DIRECTOR DAVID ALAN MILLER, HEINRICH MEDICUS MUSIC DIRECTOR Grammy®Award-winning conductor David Alan Miller has established a reputation as one of the leading American conductors of his generation. Music Director of the Albany Symphony since 1992, Mr. Miller has proven himself a creative and compelling orchestra builder. Through exploration of unusual repertoire, educational programming, community outreach and recording initiatives, he has reaffirmed the Albany Symphony’s reputation as the nation’s leading champion of American symphonic music and one of its most innovative orchestras. He and the orchestra have twice appeared at “Spring For Music,” an annual festival of America’s most creative orchestras at New York City’s Carnegie Hall. Other accolades include Columbia University’s 2003 Ditson Conductor’s Award, the oldest award honoring conductors for their commitment to American music, the 2001 ASCAP Morton Gould Award for Innovative Programming and, in 1999, ASCAP’s first-ever Leonard Bernstein Award for Outstanding Educational Programming. Frequently in demand as a guest conductor, Mr. Miller has worked with most of America’s major orchestras, including the orchestras of Baltimore, Chicago, Cleveland, Detroit, Houston, Indianapolis, Los Angeles, New York, Philadelphia, Pittsburgh and San Francisco, as well as the New World Symphony, the Boston Pops and the New York City Ballet. In addition, he has appeared frequently throughout Europe, Australia and the Far East as guest conductor. He made his first guest appearance with the BBC Scottish Symphony in March, 2014. Mr. Miller received his Grammy Award in January, 2014 for his Naxos recording of John Corigliano’s “Conjurer,” with the Albany Symphony and Dame Evelyn Glennie. -

Molina 2-25.Indd

Dr. Moore’s sponsors include Pearl Drums/Adams Musical Instruments, REMO Drumheads, The Percussion Music of Marc Mellits SABIAN Cymbals, Black Swamp Percussion, and Vic Firth sticks and mallets. Featuring the Ninkasi Percussion Group Gregory Lyons is Associate Professor of Music and the James Alvey Smith Endowed Professor at Louisiana Tech University where he teaches applied percussion, directs the percussion ensemble, Smith Recital Hall coaches the drum line, and coordinates the area of instrumental music education. Formerly, he was an assistant band director in the Missouri public schools where he taught percussion and Tuesday, February 25, 2020 conducted beginning and intermediate bands. He earned the Doctor of Musical Arts degree 4:30 p.m. in percussion performance from The Ohio State University, the Master of Music degree in percussion performance from Central Michigan University, and the Bachelor of Music Education degree from the Wheaton College Conservatory. MARC MELLITS This Side of Twilight (2010) As a solo and ensemble performer, Dr. Lyons has made appearances in Missouri, Arkansas, (b. 1966) Illinois, Ohio, Texas, Louisiana, Oklahoma, Michigan, and California. He has performed at the Red (2008) Percussive Arts Society International Convention’s Technology Day (2014) and the National I. Moderately funky Conference on Percussion Pedagogy (2013, 2016, 2017). He was a semi-fi nalist in the Southern II. Fast, aggressive, vicious California International Marimba Competition (2009). He has performed with the West Shore III. Moderate, with motion Symphony Orchestra (Muskegon, MI), the Lansing Symphony Orchestra (Lansing, MI), the IV. Slow, with motion Monroe Symphony Orchestra (Monroe, LA), the Shreveport Symphony Orchestra (Shreveport, V. -

Two Chamber Music Concerts

School of Music TWO STUDENT CHAMBER MUSIC CONCERTS David Requiro, director MONDAY, APRIL 21, 2014 SCHNEEBECK CONCERT HALL 6 P.M. AND 7:30 P.M. CONCERT I | 6 p.m. Notturno in E-flat Major, Opus 148, D. 897 ...................... Franz Schubert (1797–1828) Trio Consonare Jonathan Mei ‘16, violin Faithlina Chan ‘16, cello Jinshil Yi ‘14, piano Coached by David Requiro Variations on a Theme by Haydn for Two Pianos, Opus 58b .......Johannes Brahms Variations I–VI (1833–1897) Flügel x 2 Taylor Gonzales ’17, and Glenna Toomey ‘15, two pianos, four hands Coached by Duane Hulbert Summer Music for Wind Quintet, Opus 31 ...................... Samuel Barber (1910–1981) Whitney Reveyrand ‘15, flute David Brookshier ‘15, oboe Delaney Pearson ‘15, clarinet Emily Neville ‘14, bassoon Matthew Wasson ‘14, horn Coached by Paul Rafanelli Clarinet Quintet in A Major, K. 581 ..............................W.A. Mozart I. Allegro (1756–1791) IV. Allegretto con variazioni Larissa Freier ‘17, and Sarah Tucker ‘17, violins Sarah Mueller ‘17, viola Alana Roth ‘14, cello Jenna Tatiyatrairong ‘16, clarinet Coached by David Requiro Piano Trio in D Minor, Opus 32 ............................... Anton Arensky I. Allegro moderato (1861–1906) The Morpheus Trio Spencer Dechenne ‘15, violin Bronwyn Hagerty ‘15, cello Brenda Miller ‘15, piano Coached by David Requiro CONCERT II | 7:30 p.m. Piano Quartet in C Minor, Opus 60 ..........................Johannes Brahms I. Allegro non troppo III. Andante Emily Brothers ‘14, violin Henry DeMarais, viola, guest Anna Schierbeek ‘16, cello Imanuel Chen ‘15, piano Coached by David Requiro String Quartet in B Minor, Opus 11 ............................ Samuel Barber I. Molto Allegro e appassionato (1910–1981) Barbershoppe Quartet Clara Fuhrman ‘16, and Brandi Main ‘16, violins Kimberly Thuman ‘16, viola William Spengler ‘17, cello Coached by David Requiro String Trio No. -

KAMRAN INCE Symphony No

572554bk Ince Sym2:New 6-page template A 6/5/11 11:37 AM Page 1 KAMRAN INCE Symphony No. 2 ‘Fall of Constantinople’ Concerto for Orchestra • Piano Concerto Bilkent Symphony Orchestra • Ince • Metin LEFT: Kamran Ince plays his Piano Concerto with the Bilkent Symphony Orchestra, Is¸ın Metin conducting (Emre Unlenen) ABOVE: Is¸ın Metin (Mehmet Caglarer) • RIGHT: Kamran Ince conducts the Bilkent Symphony Orchestra in his Concerto for Orchestra, Turkish Instruments and Voices (Deniz Hughes) BELOW RIGHT: The Bilkent Youth Choir (Mehmet Caglarer) BELOW: Kamran Ince (Merih Akogul) C M Y K 5 8.572554 6 8.572554 572554bk Ince Sym2:New 6-page template A 6/5/11 11:37 AM Page 2 Kamran Ince (b. 1960) wind instruments in microtonal dissonance. A frighten- for the calm nights on the ramparts, when the bombard- Bilkent Symphony Orchestra Concerto for Orchestra, Turkish Instruments and Voices ing, massive swarm of strings follows. Those ideas recur ments cease, in the two day-night cycles in the opening The Bilkent Symphony Orchestra was founded in 1993 as an original artistic project of Bilkent University. Developed Symphony No. 2 ‘Fall of Constantinople • Piano Concerto • Infrared Only throughout the work; they go off like alarms and typically movement, The City and the Walls. by the Faculty of Music and Performing Arts, the orchestra is composed of over ninety proficient artists and alert us to the start of a new episode – but they often Those two ideas permeate the symphony and help us academicians of the Faculty from Turkey and twelve countries. With these characteristics the Bilkent Symphony In 1980, when Kamran Ince landed in America after Concerto for Orchestra, Turkish Instruments and Voices contrast sharply with what they announce, which to locate ourselves within its sprawling story. -

Earshot Jazz Festival in November, P 4

A Mirror and Focus for the Jazz Community Nov 2005 Vol. 21, No. 11 EARSHOT JAZZSeattle, Washington Earshot Jazz Festival in November, P 4 Conversation with Randy Halberstadt, P 21 Ballard Jazz Festival Preview, P 23 Gary McFarland Revived on Film, P 25 PHOTO BY DANIEL SHEEHAN EARSHOT JAZZ A Mirror and Focus for the Jazz Community ROCKRGRL Music Conference Executive Director: John Gilbreath Earshot Jazz Editor: Todd Matthews Th e ROCKRGRL Music Conference Highlights of the 2005 conference Editor-at-Large: Peter Monaghan 2005, a weekend symposium of women include keynote addresses by Patti Smith Contributing Writers: Todd Matthews, working in all aspects of the music indus- and Johnette Napolitano; and a Shop Peter Monaghan, Lloyd Peterson try, will take place November 10-12 at Talk Q&A between Bonnie Raitt and Photography: Robin Laanenen, Daniel the Madison Renaissance Hotel in Seat- Ann Wilson. Th e conference will also Sheehan, Valerie Trucchia tle. Th ree thousand people from around showcase almost 250 female-led perfor- Layout: Karen Caropepe Distribution Coordinator: Jack Gold the world attended the fi rst ROCKRGRL mances in various venues throughout Mailing: Lola Pedrini Music Conference including the legend- downtown Seattle at night, and a variety Program Manager: Karen Caropepe ary Ronnie Spector and Courtney Love. of workshops and sessions. Registra- Icons Ann and Nancy Wilson of Heart tion and information at: www.rockrgrl. Calendar Information: mail to 3429 were honored with the fi rst Woman of com/conference, or email info@rockrgrl. Fremont Place #309, Seattle WA Valor lifetime achievement Award. com. 98103; fax to (206) 547-6286; or email [email protected] Board of Directors: Fred Gilbert EARSHOT JAZZ presents.. -

Concert: Ithaca College Contemporary Ensemble Ithaca College Contemporary Ensemble

Ithaca College Digital Commons @ IC All Concert & Recital Programs Concert & Recital Programs 4-15-2013 Concert: Ithaca College Contemporary Ensemble Ithaca College Contemporary Ensemble Jorge Grossmann Jeffery Meyer Ivy Walz Wendy Mehne See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Ithaca College Contemporary Ensemble; Grossmann, Jorge; Meyer, Jeffery; Walz, Ivy; Mehne, Wendy; Faria, Richard; Birr, Diane; and Hayghe, Jennifer, "Concert: Ithaca College Contemporary Ensemble" (2013). All Concert & Recital Programs. 2504. https://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs/2504 This Program is brought to you for free and open access by the Concert & Recital Programs at Digital Commons @ IC. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Concert & Recital Programs by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ IC. Authors Ithaca College Contemporary Ensemble, Jorge Grossmann, Jeffery Meyer, Ivy Walz, Wendy Mehne, Richard Faria, Diane Birr, and Jennifer Hayghe This program is available at Digital Commons @ IC: https://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs/2504 Ithaca College Contemporary Ensemble Jorge Grossmann and Jeffery Meyer, co-directors Featuring: Ivy Walz, mezzo-soprano Wendy Mehne, flute Richard Faria, clarinet Diane Birr, piano Jennifer Hayghe, piano Jeffery Meyer, conductor and piano Hockett Family Recital Hall Monday April 15th, 2013 8:15 pm Program Spam (1995) Marc Mellits (b. 1966) Maya Holmes, flute James Conte, clarinet Laura Sciavolino, violin Jacqueline Georgis, cello Jeffery Meyer, piano* Richard Faria, conductor* From Piano Etudes David Rakowski No. 40 Strident - Stride piano étude (2002) (b. 1958) No. 15 The Third, Man - Étude on thirds (1997) No. 68 Absofunkinlutely - Funk étude (2005) Diane Birr, piano* Mento (1995) David Rakowski I.