John Howard Yoder's Social Ethics As Lens for Re

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nigeria's Constitution of 1999

PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:42 constituteproject.org Nigeria's Constitution of 1999 This complete constitution has been generated from excerpts of texts from the repository of the Comparative Constitutions Project, and distributed on constituteproject.org. constituteproject.org PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:42 Table of contents Preamble . 5 Chapter I: General Provisions . 5 Part I: Federal Republic of Nigeria . 5 Part II: Powers of the Federal Republic of Nigeria . 6 Chapter II: Fundamental Objectives and Directive Principles of State Policy . 13 Chapter III: Citizenship . 17 Chapter IV: Fundamental Rights . 20 Chapter V: The Legislature . 28 Part I: National Assembly . 28 A. Composition and Staff of National Assembly . 28 B. Procedure for Summoning and Dissolution of National Assembly . 29 C. Qualifications for Membership of National Assembly and Right of Attendance . 32 D. Elections to National Assembly . 35 E. Powers and Control over Public Funds . 36 Part II: House of Assembly of a State . 40 A. Composition and Staff of House of Assembly . 40 B. Procedure for Summoning and Dissolution of House of Assembly . 41 C. Qualification for Membership of House of Assembly and Right of Attendance . 43 D. Elections to a House of Assembly . 45 E. Powers and Control over Public Funds . 47 Chapter VI: The Executive . 50 Part I: Federal Executive . 50 A. The President of the Federation . 50 B. Establishment of Certain Federal Executive Bodies . 58 C. Public Revenue . 61 D. The Public Service of the Federation . 63 Part II: State Executive . 65 A. Governor of a State . 65 B. Establishment of Certain State Executive Bodies . -

SEMBENE in SENEGAL Radical Art in Neo-Colonial Society

SEMBENE IN SENEGAL Radical Art in Neo-colonial Society by Fírinne Ní Chréacháin A thesis submitted to the Centre of West African Studies of the University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December 1997 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. AUTHOR’SSTATEMENTCONCERNINGELECTRONICVERSION Theoriginalofthisthesiswasproducedin1997onaveryoldAmstradwordͲprocessor whichwouldhaveproducedaverypoorͲqualityscannedversion. InsubmittingthiselectronicversionforinclusionintheUBIRArepositoryin2019,I,the author,havemadethefollowingchanges: FRONTPAGES:Ichangedtheorderofthepages,puttingthepersonalpages(dedicationand acknowledgements)first. TABLEOFCONTENTS:Iremovedtheclumsylookingsubsubtitlestoproduceacleanerlook. BODYOFTEXT:Nochangesapartfrominsertionofsomeextrasubtitlesandsubsubtitlesto enhanceaccessibility. BIBLIOGRAPHY:Iaddedthreeentries,ADOTEVI,ENAGNONandKANE,inadvertentlyomitted inoriginal. Signed DrFírinneNíChréacháin 7May2019 FOR YETUNDE AND ALL GOD’S BITS OF WOOD BANTY -

Newswatch April 24 1995.Pdf

Canada.. C$2.00 Ghana C500 Saudi Arabia RislCOO Germany DM 3 SO CFA Zone 500 USA $3 50 Italy L 2.000 Sierra Leone Le 300 Zimbabwe $130 France 13F Kenya Sh 20 UK fi 50 The Gambia D4 Liberia L$ 2 00 When you’re Close-Up that’s when Close-Up counts. Flashing white teeth and a fresh mouth... that’s what you get from the Fluoride and mouthwash in Close-Up. Get fresh breath confidence from Close-Up. Flashing white teeth and fresh sweet breath... that’s Close-up appeal! L124P90 aapn0026 Outline Newswtâdi APRIL 24,1995 NIGERIA’S WEEKLY NEWSMAGAZINE VOL. 21 NO. 17 Nigeria: Cover: 12 The Emir of Laf iagi, dethroned by his people, returns to the throne • Former president of Nigeria Labour Not Yet Freedom Congress, Pascal Bafyau, wants his job back • Six Newswatch journalists begin a legal struggle to make Oni- Moshood Abiola's accep Okpaku pay for wrongful detention tance of conditional release • Kayode Soyinka, former staff of Newswatch, launches his own raises hopes of his freedom magazine but government shuts the door on his face Africa: A cease-fire hammered out in Sudanby former US president, Jimmy Carter, is threatened Nigeria: 18 World: 27 French presidential candidates are Not the Right time set to test their strength in a first round ballot Tom Ddmi says the Abacha Business & Economy: 30 administration requires more time to put in place Efforts to stop gas flaring in Nigeria structures for an enduring depend on the availability of funds democracy Letters Cartoon Momah Business & N CO O) r CM v Editorial Suite Economy: 28 T- Essay CO A Winning Dialogue Formular Passages CBN's intervention at the Cover: forex market may be the Design by Tunde Soyinka magic to stabilise the value of the naira Newswatch (ISSN 0189-8892) is published weekly by Newswatch Communications Umited, No. -

HISTORY: Abia State Nigeria Was Carved out of Old Imo State on August 27, 1991 with Umuahia As Its Capital

iI HISTORY: Abia State Nigeria was carved out of old Imo State on August 27, 1991 with Umuahia as its capital. The State is made up of seventeen (17) Local Government Areas. It is one of the five states in the Southeast geopolitical zone of Nigeria. The name ABIA was coined from the first letters of the names of the geo-political groups that originally made up the State, namely: Aba, Bende, Isuikwuato and Afikpo. Today, Afikpo is in Ebonyi State that was created in October, 1996. GEOGRAPHICAL LOCATION AND CLIMATE: Abia State is situated between latitudes 04°45' and 06° 07f north and longitudes 07° 00' and 08° IO1 east. Imo, Anambra and Rivers border it in the west, northwest and southwest respectively. AN INVESTMENT HAVEN GUIDE TO INVESTMENT IN ABIA STATE To the north, northeast, east and southeast, it is bordered by Enugu, Ebonyi, Cross-River an Akwa Ibom States respectively. It belongs to the Southeast geopolitical zone of Nigeria and covers a landmass of 5,833.77 sq. km. The State is located within the forest belt of Nigeria with a temperature range of between 20°C -36°C lying within the tropics. It has the dry and rainy seasons - (October - March and April September respectively). POPULATION: By the projection of the National Bureau of Statistics, based on the 1991 census figure of I. million, Abia State was expected to have a population of 3.51 million. In 2006 the National Population Commission allocated 2,833,999 as the population of Abia State. This figure is being contested at the population tribunal. -

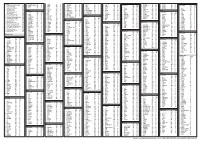

Directory of Polling Units Abia State

FEDERAL REPUBLIC OF NIGERIA Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC) ABIA STATE DIRECTORY OF POLLING UNITS Revised January 2015 DISCLAIMER The contents of this Directory should not be referred to as a legal or administrative document for the purpose of administrative boundary or political claims. Any error of omission or inclusion found should be brought to the attention of the Independent National Electoral Commission. INEC Nigeria Directory of Polling Units Revised January 2015 Page i Table of Contents Pages Disclaimer................................................................................. i Table of Contents ………………………………………………… ii Foreword.................................................................................. iv Acknowledgement.................................................................... v Summary of Polling Units......................................................... 1 LOCAL GOVERNMENT AREAS Aba North ………………………………………………….. 2-15 Aba South …………………………………………………. 16-28 Arochukwu ………………………………………………… 29-36 Bende ……………………………………………………… 37-45 Ikwuano ……………………………………………………. 46-50 Isiala Ngwa North ………………………………………… 51-56 Isiala Ngwa South ………………………………………… 57-63 Isuikwuato …………………………………………………. 64-69 Obingwa …………………………………………………… 70-79 Ohafia ……………………………………………………… 80-91 Osisioma Ngwa …………………………………………… 92-95 Ugwunagbo ……………………………………………….. 96-101 Ukwa East …………………………………………………. 102-105 Ukwa West ………………………………………..………. 106-110 Umuahia North …………………………………..……….. 111-118 Umuahia South …………………………………..……….. 119-124 Umu-Nneochi -

ABIA ORGANIZED CRIME FACTS.Cdr

ORGANIZED CRIME FACTS ABIA STATE Abia State with an estimated population of 2.4 million and records straight. predominantly of Igbo origin, has recently come under the limelight due to heightened insecurity trailing South-Eastern Through its bi-annual publications of organized crime facts states. With the spike in attacks of police officers and police of each of the states in Nigeria, Eons Intelligence attempts stations, correctional facilities and other notable public and to augment the dearth of updated and timely release of private properties and persons in some selected Eastern national crime statistics by objectively providing an States of the Nation, speculations have given rise to an assessment of the situation to provide answers that will underlying tone that denotes all Eastern States as assist all stakeholders to make an informed decision. presenting an uncongenial image of a hazardous zone, Abia State, which shares a boundary with Imo State to the which fast deteriorates into a notorious terrorist region. West, has started gaining the reputation for being one of the The myth of more violent South-Eastern States than their violent Eastern states in the light of recent insecurity Northern counterparts cuts across all social media and happenings in Imo State. Some detractors have gone to the social status amongst the elites, expatriates, the rich, the extent of relying on personal perceptions, presumptions, poor, and the ugly, sending culpable fears amidst all. one-off incidents, conspiracy deductions, the power of invisible forces, or the scramble for resources to form an Hence, it is necessary to use verified statistics that use a opinion. -

From Guardian Online 6 June 2014 Kaye Whiteman Obituary (Died 17 May 2014)

From Guardian Online 6 June 2014 Kaye Whiteman obituary (Died 17 May 2014) (At Friends’ School 1947 to 1952 – YG 53) Journalist who witnessed and documented key moments in modern African history For many years, Kaye Whiteman edited West Africa magazine. Photograph: Gerald Mclean The journalist and editor Kaye Whiteman, who has died aged 78, possessed a remarkable knowledge of Africa, its peoples and those who governed them. He met most of the key African leaders from the period of decolonisation and independence, both English- and French-speaking, and was in touch with many of those involved in public service throughout the continent. His area of particular expertise was west Africa, and above all Nigeria. He first went there and to nearby Ghana in 1964 as the deputy editor of the weekly West Africa magazine. He returned to Ghana the following year to cover the summit of the Organisation of African Unity (OAU), which he described in his article Ghana at 50 in Africa Today (March 2007) as "an African event of unrivalled spectacle, when all Africa came to pay tribute to the great pioneer of independence", a reference to Kwame Nkrumah, Ghana's first president. Kaye also reported on the Nigerian civil war of 1967-70 for the Times, witnessing the surrender of the Biafran general Philip Effiong to General Yakubu Gowon. In 1973 he went to Brussels, as a senior information officer for the European commission, dealing with development issues, especially in Africa. In the meantime, the ownership of West Africa magazine moved from Britain to Nigeria, and in 1982 Kaye succeeded David Williams as editor, later becoming editor-in-chief and general manager. -

Abia State NEW.Cdr

VISION “To be the leading pro-poor service delivery institution in Nigeria” MISSION “Mobilizing resources, improving skills and knowledge to promote Community Driven Development (CDD) for positive impact on the poor and vulnerable in Nigeria” 29 558 States & FCT LGAs 4,300 14,856 37,904,289 Communities Micro Projects Beneficiaries CSDP...Promoting Community Driven Development 20 9 SEETHROUGH 1 COMMUNITY AND SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT PROJECT (World Bank Assisted) WHO WE ARE Community and Social Development Project (CSDP) is a scales up of the pilot Community-based Poverty Reduction Project (CPRP) and Local Empowerment and Environment Management Project (LEEMP). CSDP is therefore and intervention that has built on the CPRP and LEEMP structures to effectively target socio-economic and environment /natural resources management infrastructural projects, at the community level as well as to improve Local Government Area (LGA) responsibility to service delivery. To support the implementation of the CSDP, the Federal Government of Nigeria sought and obtained financial assistance from the International Development Association (IDA) of the World Bank Group. The Original closing date of the original credit for the Project, was December 31, 2013. However, to allow full disbursement, the closing date for the original credit was extended to December 31, 2014. As a result of the impressive performance of the CSDP, Additional Financing of US $215 million was obtained for the project and the closing date of the new credit is expected to be June 30, 2020. OUR CORE VALUES: Quality Service Networking & Cooperation Creativity Integrity & Transparency OBJECTIVES: To Increase access by the poor people, and particularly by internally displaced and vulnerable people in the North East of Nigeria to improved social and natural resources infrastructure services in a sustainable manner throughout Nigeria. -

Abia STATE-WIDE RAPID HEALTH FACILITY ASSESSMENT

Report of the Abia STATE-WIDE RAPID HEALTH FACILITY ASSESSMENT In Preparation for Elimination of Mother-to-Child Transmission of HIV AUGUST 2013 Report of the Abia STATE-WIDE RAPID HEALTH FACILITY ASSESSMENT In Preparation for Elimination of Mother-to-Child Transmission of HIV AUGUST 2013 This publication may be freely reviewed, quoted, reproduced, or translated, in full or in part, provided the source is acknowledged. The mention of specific organizations does not imply endorsement and does not suggest that they are recommended by the Abia State Ministry of Health over others of a similar nature not mentioned. First edition copyright © 2013 Abia State Ministry of Health, Nigeria Citation: Abia State Ministry of Health and FHI 360. 2013. Abia State-wide Rapid Health Facility Assessment, Nigeria: Abia State Ministry of Health and FHI 360 The Abia State-wide Rapid Health Facility Assessment was supported in part by the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID). FHI 360 provided assistance to the Abia State Government to conduct this assessment. Financial assistance was provided by USAID under the terms of the Cooperative Agreement AID-620-A-00002, of the Strengthening Integrated Delivery of HIV/ AIDS Services Project. This report does not necessarily reflect the views of FHI 360, USAID or the United States Government. Table of Contents Foreword ........................................................................................................................................................................... iii Acknowledgements -

States and Lcdas Codes.Cdr

PFA CODES 28 UKANEFUN KPK AK 6 CHIBOK CBK BO 8 ETSAKO-EAST AGD ED 20 ONUIMO KWE IM 32 RIMIN-GADO RMG KN KWARA 9 IJEBU-NORTH JGB OG 30 OYO-EAST YYY OY YOBE 1 Stanbic IBTC Pension Managers Limited 0021 29 URU OFFONG ORUKO UFG AK 7 DAMBOA DAM BO 9 ETSAKO-WEST AUC ED 21 ORLU RLU IM 33 ROGO RGG KN S/N LGA NAME LGA STATE 10 IJEBU-NORTH-EAST JNE OG 31 SAKI-EAST GMD OY S/N LGA NAME LGA STATE 2 Premium Pension Limited 0022 30 URUAN DUU AK 8 DIKWA DKW BO 10 IGUEBEN GUE ED 22 ORSU AWT IM 34 SHANONO SNN KN CODE CODE 11 IJEBU-ODE JBD OG 32 SAKI-WEST SHK OY CODE CODE 3 Leadway Pensure PFA Limited 0023 31 UYO UYY AK 9 GUBIO GUB BO 11 IKPOBA-OKHA DGE ED 23 ORU-EAST MMA IM 35 SUMAILA SML KN 1 ASA AFN KW 12 IKENNE KNN OG 33 SURULERE RSD OY 1 BADE GSH YB 4 Sigma Pensions Limited 0024 10 GUZAMALA GZM BO 12 OREDO BEN ED 24 ORU-WEST NGB IM 36 TAKAI TAK KN 2 BARUTEN KSB KW 13 IMEKO-AFON MEK OG 2 BOSARI DPH YB 5 Pensions Alliance Limited 0025 ANAMBRA 11 GWOZA GZA BO 13 ORHIONMWON ABD ED 25 OWERRI-MUNICIPAL WER IM 37 TARAUNI TRN KN 3 EDU LAF KW 14 IPOKIA PKA OG PLATEAU 3 DAMATURU DTR YB 6 ARM Pension Managers Limited 0026 S/N LGA NAME LGA STATE 12 HAWUL HWL BO 14 OVIA-NORTH-EAST AKA ED 26 26 OWERRI-NORTH RRT IM 38 TOFA TEA KN 4 EKITI ARP KW 15 OBAFEMI OWODE WDE OG S/N LGA NAME LGA STATE 4 FIKA FKA YB 7 Trustfund Pensions Plc 0028 CODE CODE 13 JERE JRE BO 15 OVIA-SOUTH-WEST GBZ ED 27 27 OWERRI-WEST UMG IM 39 TSANYAWA TYW KN 5 IFELODUN SHA KW 16 ODEDAH DED OG CODE CODE 5 FUNE FUN YB 8 First Guarantee Pension Limited 0029 1 AGUATA AGU AN 14 KAGA KGG BO 16 OWAN-EAST -

South East Capital Budget Pull

2014 FEDERAL CAPITAL BUDGET Of the States in the South East Geo-Political Zone By Citizens Wealth Platform (CWP) (Public Resources Are Made To Work And Be Of Benefit To All) 2014 FEDERAL CAPITAL BUDGET Of the States in the South East Geo-Political Zone Citizens Wealth Platform (CWP) (Public Resources Are Made To Work And Be Of Benefit To All) ii 2014 FEDERAL CAPITAL BUDGET Of the States in the South East Geo-Political Zone Compiled by Centre for Social Justice For Citizens Wealth Platform (CWP) (Public Resources Are Made To Work And Be Of Benefit To All) iii First Published in October 2014 By Citizens Wealth Platform (CWP) C/o Centre for Social Justice 17 Yaounde Street, Wuse Zone 6, Abuja. Website: www.csj-ng.org ; E-mail: [email protected] ; Facebook: CSJNigeria; Twitter:@censoj; YouTube: www.youtube.com/user/CSJNigeria. iv Table of Contents Acknowledgement v Foreword vi Abia 1 Imo 17 Anambra 30 Enugu 45 Ebonyi 30 v Acknowledgement Citizens Wealth Platform acknowledges the financial and secretariat support of Centre for Social Justice towards the publication of this Capital Budget Pull-Out vi PREFACE This is the third year of compiling Capital Budget Pull-Outs for the six geo-political zones by Citizens Wealth Platform (CWP). The idea is to provide information to all classes of Nigerians about capital projects in the federal budget which have been appropriated for their zone, state, local government and community. There have been several complaints by citizens about the large bulk of government budgets which makes them unattractive and not reader friendly. -

Physicochemical Studies of Water from Selected Boreholes in Umuahia North Local Government Area, in Abia State, Nigeria Internat

Available online at www.ijpab.com ISSN: 2320 – 7051 Int. J. Pure App. Biosci. 1 (3): 34-44 (2013) Research Article International Journal of Pure & Applied Bioscience Physicochemical Studies of Water from Selected Boreholes in Umuahia North Local Government Area, in Abia State, Nigeria N. I. Onwughara* 1, 2 , V. I. E. Ajiwe 2 and H. O. Nnabuenyi 2 1Quality Assurance Department, GlaxoSmithKline Consumer Nigeria Plc Igbesa Road Agbara Ogun State, Nigeria 2Department of Pure and Industrial Chemistry, Faculty of Physical Sciences, Nnamdi Azikiwe University Awka, P.M.B. 5052 Awka, Anambra State, Nigeria. *Corresponding Author Email: [email protected] ______________________________________________________________________________ ABSTRACT The physicochemical parameters of water from 12 boreholes from 12 different communities in Umuahia North Local Government Area, Abia State, Nigeria were determined within the period of six months (February to July) 2011 to investigate their quality. Analyses were done on water samples for Temperature, pH, Electrical conductivity (EC), Total dissolved solids (TDS), Total suspended solids (TSS), Dissolved Oxygen,(DO), Biochemical Oxygen Demand (BOD), Chemical Oxygen Demand (COD), Alkalinity, Acidity, Total hardness, Turbidity, Salinity, Nitrate, Phosphate, Calcium ion, and Magnesium ion using standard methods and evaluated with the World Health Organization standards. All physicochemical parameters analysed in borehole water samples were within recommended standards except the following: total suspended solids (TSS) ranged from 31.3 to 55.0mg/l with a mean value of 37.9±7.67 mg/l, salinity151-227 mg/l (171±37.6 mg/l mean), nitrate 12.4-35.4mg/l (19.6±14.5 mg/l mean), phosphate 6.22-7.97mg/l (6.99±1.74 mean), biochemical oxygen demand (BOD) values 5.35-15.9 mg/l (9.92±5.15mg/l mean) and Dissolved Oxygen (DO) 29.4-33.5 mg/l (31.6±3.33mg/l mean) all generally above WHO permissible limit respectively.