Gabapentin Enacarbil Extended&

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Neurontin (Gabapentin)

Texas Prior Authorization Program Clinical Criteria Drug/Drug Class Gabapentin Clinical Criteria Information Included in this Document Neurontin (gabapentin) • Drugs requiring prior authorization: the list of drugs requiring prior authorization for this clinical criteria • Prior authorization criteria logic: a description of how the prior authorization request will be evaluated against the clinical criteria rules • Logic diagram: a visual depiction of the clinical criteria logic • Supporting tables: a collection of information associated with the steps within the criteria (diagnosis codes, procedure codes, and therapy codes); provided when applicable • References: clinical publications and sources relevant to this clinical criteria Note: Click the hyperlink to navigate directly to that section. Gralise (gabapentin Extended Release) • Drugs requiring prior authorization: the list of drugs requiring prior authorization for this clinical criteria • Prior authorization criteria logic: a description of how the prior authorization request will be evaluated against the clinical criteria rules • Logic diagram: a visual depiction of the clinical criteria logic • Supporting tables: a collection of information associated with the steps within the criteria (diagnosis codes, procedure codes, and therapy codes); provided when applicable • References: clinical publications and sources relevant to this clinical criteria Note: Click the hyperlink to navigate directly to that section. March 29, 2019 Copyright © 2019 Health Information Designs, LLC 1 Horizant -

Preventive Report Appendix

Title Authors Published Journal Volume Issue Pages DOI Final Status Exclusion Reason Nasal sumatriptan is effective in treatment of migraine attacks in children: A Ahonen K.; Hamalainen ML.; Rantala H.; 2004 Neurology 62 6 883-7 10.1212/01.wnl.0000115105.05966.a7 Deemed irrelevant in initial screening Seasonal variation in migraine. Alstadhaug KB.; Salvesen R.; Bekkelund SI. Cephalalgia : an 2005 international journal 25 10 811-6 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2005.01018.x Deemed irrelevant in initial screening Flunarizine, a calcium channel blocker: a new prophylactic drug in migraine. Amery WK. 1983 Headache 23 2 70-4 10.1111/j.1526-4610.1983.hed2302070 Deemed irrelevant in initial screening Monoamine oxidase inhibitors in the control of migraine. Anthony M.; Lance JW. Proceedings of the 1970 Australian 7 45-7 Deemed irrelevant in initial screening Prostaglandins and prostaglandin receptor antagonism in migraine. Antonova M. 2013 Danish medical 60 5 B4635 Deemed irrelevant in initial screening Divalproex extended-release in adolescent migraine prophylaxis: results of a Apostol G.; Cady RK.; Laforet GA.; Robieson randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. WZ.; Olson E.; Abi-Saab WM.; Saltarelli M. 2008 Headache 48 7 1012-25 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2008.01081.x Deemed irrelevant in initial screening Divalproex sodium extended-release for the prophylaxis of migraine headache in Apostol G.; Lewis DW.; Laforet GA.; adolescents: results of a stand-alone, long-term open-label safety study. Robieson WZ.; Fugate JM.; Abi-Saab WM.; 2009 Headache 49 1 45-53 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2008.01279.x Deemed irrelevant in initial screening Safety and tolerability of divalproex sodium extended-release in the prophylaxis of Apostol G.; Pakalnis A.; Laforet GA.; migraine headaches: results of an open-label extension trial in adolescents. -

Conjugation of Tryptamine to Biologically Active Carboxylic Acids in Order to Create Prodrugs

ISSN 2380-5064 | The Arsenal is published by the Augusta University Libraries | http://guides.augusta.edu/arsenal Volume 4, Issue 1 (2021) Special Edition Issue CONJUGATION OF TRYPTAMINE TO BIOLOGICALLY ACTIVE CARBOXYLIC ACIDS IN ORDER TO CREATE PRODRUGS Colin Miller, Jr. and Iryna O. Lebedyeva Citation Miller, C., Jr., & Lebedyeva, I. O. (2021). Conjugation of tryptamine to biologically active carboxylic acids in order to create prodrugs. The Arsenal: The Undergraduate Research Journal of Augusta University, 4(1), 26. http://doi.org/10.21633/issn.2380.5064/s.2021.04.01.26 © Miller, Jr. and Lebedyeva 2021. This open access article is distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.0/). Conjugation of Tryptamine to Biologically Active Carboxylic Acids in Order to Create Prodrugs Presenter(s): Colin Miller, Jr. Author(s): Colin Miller Jr. and Iryna O. Lebedyeva Faculty Sponsor(s): Iryna O. Lebedyeva, PhD Affiliation(s): Department of Chemistry and Physics (Augusta Univ.) ABSTRACT A number of blood and brain barrier penetrating neurotransmitters contain polar functional groups. Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) is an amino acid, which is one of the primary inhibitory neurotransmitter in the brain and a major inhibitory neurotransmitter in the spinal cord. Antiepileptic medications such as Gabapentin, Phenibut, and Pregabalin have been developed to structurally represent GABA. These drugs are usually prescribed for the treatment of neuropathic pain. Since these drugs contain a polar carboxylic acid group, it affects their ability to penetrate the blood and brain barrier. To address the low bioavailability and tendency for intramolecular cyclization of Gabapentin, its less polar prodrug Gabapentin Enacarbil has been approved in 2011. -

(12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 8,283,487 B2 Ben Moha-Lerman Et Al

USOO8283487B2 (12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 8,283,487 B2 Ben Moha-Lerman et al. (45) Date of Patent: Oct. 9, 2012 (54) PROCESSES FOR THE PREPARATION AND 2003/0176398 A1 9/2003 Gallop et al. PURIFICATION OF GABAPENTIN 2004/0077553 A1* 4/2004 Gallop et al. ................... 514, 19 2005/O154057 A1 7/2005 Estrada et al. ENACARBL 2007/0049627 A1 3, 2007 Tran (75) Inventors: Elena Ben Moha-Lerman, Kiryat Ono FOREIGN PATENT DOCUMENTS (IL); Tamar Nidam, Yehud (IL); Meital WO WO O2/10O347 12/2002 Cohen, Petach-Tikva (IL); Sharon WO WO 2005/0377.84 4/2005 Avhar-Maydan, Givataym (IL); Anna Balanov, Rehovot (IL) OTHER PUBLICATIONS X. Yuan et al. “In Situ Preparation of Zinc Salts of Unsaturated (73) Assignee: Teva Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd., Carboxylic Acids to Reinforce NBR' J. Applied Polymer Science, Petach-Tikva (IL) vol. 77, p. 2740-2748 (2000). - r J. Alexander et al. “(Acyloxy)alkyl Carbamates as Novel Biorevers (*) Notice: Subject to any disclaimer, the term of this ible Prodrugs for Amines: Increased Permeation through Biological patent is extended or adjusted under 35 Membranes”.J. Med. Chem. 1988, 31, pp. 318-322. U.S.C. 154(b) by 249 days. S.M. Rahmathullah et al. “Prodrugs for Amidines: Synthesis and Anti-Pneumocystis carinii Activity of Carbamates of 2.5-Bis(4- (21) Appl. No.: 12/626,682 amidinophenyl)furan” J. Med. Chem. 1999, 42, pp. 3994-4000. (22) Filed: Nov. 26, 2009 * cited by examiner (65) Prior Publication Data Primary Examiner — Joseph K. McKane US 2010/O160665 A1 Jun. 24, 2010 Assistant Examiner — Alicia L Otton (74) Attorney, Agent, or Firm — Arent Fox LLP Related U.S. -

More Treatments on Deck for Alcohol Use Disorder

News & Analysis Medical News & Perspectives More Treatments on Deck for Alcohol Use Disorder Jeff Lyon hirteen years have passed since the Raye Z. Litten, PhD, acting director of the ment for AUD were actually prescribed an US Food and Drug Administration NIAAA’s Division of Medications Develop- AUD medication. T (FDA) last approved a new medica- ment and principal investigator of the trial, It is a complicated problem, says John tion to help the nation’s millions of people says the agency is “excited.” Rotrosen, MD, a psychiatrist and addiction withalcoholusedisorder(AUD)stopormod- Nevertheless, the science of alcohol ad- specialist at New York University School of erate their drinking. diction has seen its share of medicines that Medicine. “To a large extent primary care Only 3 such formulations exist, and 1, failed to live up to their early promise dur- physicians don’t screen for alcoholism,” he disulfiram, dates to the Prohibition era. ing full-scale testing. So Litten said the said. “When they do, they may note it, but Known commercially as Antabuse and agency isn’t putting all its eggs in one bas- don’t really do anything about it.” introduced in 1923, it makes people memo- ket. “You need as many weapons as pos- As far as the failure to prescribe exist- rably ill if they ingest alcohol, but it doesn’t sible to treat a complex disease like alcohol ing medications for AUD, Rotrosen blames stop the cravings. The other 2, naltrexone use disorder,” he said. a lack of knowledge. “A lot of doctors in and acamprosate, approved in 1994 and But therein lies a second difficulty. -

A Comparative Effectiveness Meta-Analysis of Drugs for the Prophylaxis of Migraine Headache

University of South Florida Masthead Logo Scholar Commons School of Information Faculty Publications School of Information 7-2015 A Comparative Effectiveness Meta-Analysis of Drugs for the Prophylaxis of Migraine Headache Authors: Jeffrey L. Jackson, Elizabeth Cogbill, Rafael Santana-Davila, Christina Eldredge, William Collier, Andrew Gradall, Neha Sehgal, and Jessica Kuester OBJECTIVE: To compare the effectiveness and side effects of migraine prophylactic medications. DESIGN: We performed a network meta-analysis. Data were extracted independently in duplicate and quality was assessed using both the JADAD and Cochrane Risk of Bias instruments. Data were pooled and network meta-analysis performed using random effects models. DATA SOURCES: PUBMED, EMBASE, Cochrane Trial Registry, bibliography of retrieved articles through 18 May 2014. ELIGIBILITY CRITERIA FOR SELECTING STUDIES: We included randomized controlled trials of adults with migraine headaches of at least 4 weeks in duration. RESULTS: Placebo controlled trials included alpha blockers (n = 9), angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (n = 3), angiotensin receptor blockers (n = 3), anticonvulsants (n = 32), beta-blockers (n = 39), calcium channel blockers (n = 12), flunarizine (n = 7), serotonin reuptake inhibitors (n = 6), serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (n = 1) serotonin agonists (n = 9) and tricyclic antidepressants (n = 11). In addition there were 53 trials comparing different drugs. Drugs with at least 3 trials that were more effective than placebo for episodic migraines -

Gabapentinoids: Pharmacokinetics, Pharmacodynamics and Considerations for Clinical Practice

912496BJP British Journal of PainChincholkar Special Issue Article British Journal of Pain 1 –11 Gabapentinoids: pharmacokinetics, © The British Pain Society 2020 Article reuse guidelines: sagepub.com/journals-permissions pharmacodynamics and considerations DOI:https://doi.org/10.1177/2049463720912496 10.1177/2049463720912496 for clinical practice journals.sagepub.com/home/bjp Mahindra Chincholkar Abstract The gabapentinoids are often recommended as first-line treatments for the management of neuropathic pain. The differing pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic profiles can have implications for clinical practice. This article has summarised these key differences. In addition to their use in managing neuropathic pain, gabapentinoids are increasingly being used for off-label conditions despite the lack of evidence. Prescription rates for off-label conditions have overtaken that for on-label use. Similarly, the use of gabapentinoids in the perioperative period is now embedded in clinical practice despite conflicting evidence. This article summarises the risks associated with this increasing use. There is increasing evidence of the potential to cause harm in vulnerable populations such as the elderly and increasing prevalence of abuse. The risk of respiratory depression in combination with opioids is of particular concern in the context of the current opioid crisis. This article describes the practical considerations involved that might help guide appropriate prescribing practices. Keywords Gabapentin, pregabalin, pain management, adverse effects, pharmacology Introduction movement, sleep disorders, headaches, alcohol with- drawal syndrome, chronic back pain, fibromyalgia, vis- The gabapentinoid drugs gabapentin and pregabalin ceral pain and acute postoperative pain.4,5 The rate of are antiepileptic drugs that are considered as first-line new prescriptions is increasing and tripled in England 1 treatments for the management of neuropathic pain. -

Gabapentin Enacarbil (Horizant) Monograph

Gabapentin enacarbil (Horizant) Monograph ® Gabapentin Enacarbil (Horizant ) National Drug Monograph March 2012 VA Pharmacy Benefits Management Services, Medical Advisory Panel, and VISN Pharmacist Executives The purpose of VA PBM Services drug monographs is to provide a comprehensive drug review for making formulary decisions. These documents will be updated when new clinical data warrant additional formulary discussion. Documents will be placed in the Archive section when the information is deemed to be no longer current. Executive Summary: Gabapentin enacarbil (Horizant®) is a prodrug of gabapentin which binds with high affinity to the α2δ subunit of voltage-activated calcium channels in vitro studies. It is unknown how the binding of gabapentin enacarbil (GEn) to the α2δ subunit corresponds to the treatment of restless leg syndrome (RLS) symptoms. Indication: GEn is FDA approved for treatment of RLS. Pharmacokinetics: GEn is primarily excreted by the kidneys and neither gabapentin nor GEn is substrate, inhibitor, or inducer of the major CYP450 system. In addition, GEn is not an inhibitor or substrate of p-glycoprotein in vitro. Dose: The recommended dosage is 600 mg once daily taken with food at about 5 PM. Efficacy: Several studies examining GEn have shown efficacy over placebo in patients with RLS; improvement in RLS symptoms was observed within 7 days of starting treatment.6-8, 12-14 Three studies demonstrated 1200 mg/day GEn significantly reduced International Restless Legs Syndrome (IRLS) scale total score and improved Clinical Global Impression– Improvement (CGI-I) scale compared with placebo.6-8 Two studies demonstrated efficacy at lower dose of 600 mg/day GEn; however, another study did not.7,12,13 These results are comparable to those seen with dopamine agonists.8,12 Adverse Drug Events: Commonly reported adverse effects for the approved dose of 600 mg/day GEn are somnolence, sedation and dizziness. -

Ambetter 90-Day-Maintenance Drug List- 2020

Ambetter 90-Day-Maintenance Drug List Guide to this list: What is Ambetter 90‐Day‐Maintenance Drug List? Ambetter 90‐Day‐Supply Maintenance Drug List is a list of maintenance medications that are available for 90 day supply through mail order or through our Extended Day Supply Network. How do I find a pharmacy that is participating in Extended Day Supply Network? To find a retail pharmacy that is participating in our Extended Day Supply Network please consult information available under Pharmacy Resources tab on our webpage. Alternatively, you can utilize our mail order pharmacy. Information on mail order pharmacy is available in Pharmacy Resources tab on our webpage. Are all formulary drugs covered for 90 day supply? No, certain specialty and non‐specialty drugs are excluded from 90 day supply. Please consult 90‐Day‐ Supply Maintenance Drug List for information if your drug is included. A Amitriptyline HCl Acamprosate Calcium Amlodipine Besylate Acarbose Amlodipine Besylate-Atorvastatin Calcium Acebutolol HCl Amlodipine Besylate-Benazepril HCl Acetazolamide Amlodipine Besylate-Olmesartan Medoxomil Albuterol Sulfate Amlodipine Besylate-Valsartan Alendronate Sodium Amlodipine-Valsartan-Hydrochlorothiazide Alendronate Sodium-Cholecalciferol Amoxapine Alfuzosin HCl Amphetamine-Dextroamphetamine Aliskiren Fumarate Anagrelide HCl Allopurinol Anastrozole Alogliptin Benzoate Apixaban Alosetron HCl Arformoterol Tartrate Amantadine HCl Aripiprazole Amiloride & Hydrochlorothiazide Armodafinil Amiloride HCl Asenapine Maleate Amiodarone HCl Aspirin-Dipyridamole -

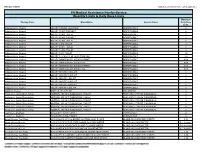

Quantity Limits/Daily Dose Limits

Effective 07/20/21 Alphabetical by Brand Name (when applicable) PA Medical Assistance Fee-for-Service Quantity Limits & Daily Dose Limits Maximum Therapy Class Brand Name Generic Name Daily Dose Limit Antipsychotics, Atypical ABILIFY 1 MG/ML SOLUTION ARIPIPRAZOLE 25 Antipsychotics, Atypical ABILIFY 10 MG DISCMELT ARIPIPRAZOLE 2 Antipsychotics, Atypical ABILIFY 10 MG TABLET ARIPIPRAZOLE 1 Antipsychotics, Atypical ABILIFY 15 MG DISCMELT ARIPIPRAZOLE 2 Antipsychotics, Atypical ABILIFY 15 MG TABLET ARIPIPRAZOLE 1 Antipsychotics, Atypical ABILIFY 2 MG TABLET ARIPIPRAZOLE 2 Antipsychotics, Atypical ABILIFY 20 MG TABLET ARIPIPRAZOLE 1 Antipsychotics, Atypical ABILIFY 30 MG TABLET ARIPIPRAZOLE 1 Antipsychotics, Atypical ABILIFY 5 MG TABLET ARIPIPRAZOLE 1.5 Antipsychotics, Atypical ABILIFY 9.75 MG/1.3 ML INJECTION VIAL ARIPIPRAZOLE 3.9 Antipsychotics, Atypical ABILIFY MAINTENA ER 300 MG SYRINGE ARIPIPRAZOLE 0.04 Antipsychotics, Atypical ABILIFY MAINTENA ER 300 MG VIAL ARIPIPRAZOLE 0.04 Antipsychotics, Atypical ABILIFY MAINTENA ER 400 MG SYRINGE ARIPIPRAZOLE 0.04 Antipsychotics, Atypical ABILIFY MAINTENA ER 400 MG VIAL ARIPIPRAZOLE 0.04 Antipsychotics, Atypical ABILIFY MYCITE 10 MG KIT ARIPIPRAZOLE 1 Antipsychotics, Atypical ABILIFY MYCITE 15 MG KIT ARIPIPRAZOLE 1 Antipsychotics, Atypical ABILIFY MYCITE 2 MG KIT ARIPIPRAZOLE 1 Antipsychotics, Atypical ABILIFY MYCITE 20 MG KIT ARIPIPRAZOLE 1 Antipsychotics, Atypical ABILIFY MYCITE 30 MG KIT ARIPIPRAZOLE 1 Antipsychotics, Atypical ABILIFY MYCITE 5 MG KIT ARIPIPRAZOLE 1 Antivirals, Herpes ABREVA 10% -

Gabapentin Misuse, Abuse, and Diversion: a Systematic Review

HHS Public Access Author manuscript Author ManuscriptAuthor Manuscript Author Addiction Manuscript Author . Author manuscript; Manuscript Author available in PMC 2017 August 29. Published in final edited form as: Addiction. 2016 July ; 111(7): 1160–1174. doi:10.1111/add.13324. Gabapentin misuse, abuse, and diversion: A systematic review Rachel V. Smith, MPH1,2,3, Jennifer R. Havens, PhD, MPH1,2, and Sharon L. Walsh, PhD1,4,5,* 1Center on Drug and Alcohol Research, Department of Behavioral Science, University of Kentucky College of Medicine, Lexington, KY 2Department of Epidemiology, University of Kentucky College of Public Health, Lexington, KY 3Department of Biostatistics, University of Kentucky College of Public Health, Lexington, KY 4Department of Pharmacology, University of Kentucky College of Medicine, Lexington, KY 5Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences, University of Kentucky College of Pharmacy, Lexington, KY Abstract Background and Aims—Since its market release, gabapentin has been presumed to have no abuse potential and subsequently has been prescribed widely off-label, despite increasing reports of gabapentin misuse. This review estimates and describes the prevalence and effects of, motivations behind, and risk factors for gabapentin misuse, abuse, and diversion. Methods—Databases were searched for peer-reviewed articles demonstrating gabapentin misuse, characterized by taking a larger dosage than prescribed or taking gabapentin without a prescription, and diversion. All types of studies were considered; grey literature was excluded. Thirty-three articles met inclusion criteria, consisting of 23 case studies and 11 epidemiological reports. Published reports came from the USA, the UK, Germany, Finland, India, South Africa, and France, and two analyzed websites not specific to a particular country. -

Augmentation Suffering and What Can Be Done About It

AUGMENTATION SUFFERING AND WHAT CAN BE DONE ABOUT IT John W. Winkelman MD PhD Massachusetts General Hospital Harvard Medical School Boston, MA Disclosure Information Type of Affiliation Commercial Entity Consultant/Honoraria UCB Research Grant Purdue Pharma UCB WHITE PAPER SUMMARY OF RECOMMENDATIONS FOR THE PREVENTION AND TREATMENT OF RLS/WED AUGMENTATION A COMBINED TASK FORCE OF THE IRLSSG, EURLSSG AND THE RLS-FOUNDATION AUGMENTATION Augmentation is a long-term (6 months-years) complication of RLS treatment with dopaminergic medications Dopaminergic (DA) medications: Levodopa (Sinemet) Pramipexole (Mirapex) Ropinirole (Requip) Rotigotine (Neupro) AUGMENTATION DEFINITION Compared to before medication was initiated there is: Advance in the time of symptom onset More intense symptoms Symptoms start faster after lying down/sitting Extension of symptoms to arms In short, RLS gets worse with medication treatment! AUGMENTATION SEVERITY EXISTS ALONG A CONTINUUM Pre-augmentation/tolerance: DA medication dose needs to be increased to maintain effectiveness but there is no change in timing of symptoms Mild: 2-4 hour advance in time of RLS symptom onset, most days Severe: 4-8 hour advance in the time of RLS symptom onset, most days Very severe: RLS symptoms present much of the day and night WHAT WORSENS RLS BUT ISN’T AUGMENTATION Iron deficiency Medication effects Antidepressants Antihistamines Dopamine blockers (anti-nausea or antipsychotics) Sleep disruption/deprivation (eg sleep apnea, insomnia) More time spent immobile (in