Gabapentin Misuse, Abuse, and Diversion: a Systematic Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Neurontin (Gabapentin)

Texas Prior Authorization Program Clinical Criteria Drug/Drug Class Gabapentin Clinical Criteria Information Included in this Document Neurontin (gabapentin) • Drugs requiring prior authorization: the list of drugs requiring prior authorization for this clinical criteria • Prior authorization criteria logic: a description of how the prior authorization request will be evaluated against the clinical criteria rules • Logic diagram: a visual depiction of the clinical criteria logic • Supporting tables: a collection of information associated with the steps within the criteria (diagnosis codes, procedure codes, and therapy codes); provided when applicable • References: clinical publications and sources relevant to this clinical criteria Note: Click the hyperlink to navigate directly to that section. Gralise (gabapentin Extended Release) • Drugs requiring prior authorization: the list of drugs requiring prior authorization for this clinical criteria • Prior authorization criteria logic: a description of how the prior authorization request will be evaluated against the clinical criteria rules • Logic diagram: a visual depiction of the clinical criteria logic • Supporting tables: a collection of information associated with the steps within the criteria (diagnosis codes, procedure codes, and therapy codes); provided when applicable • References: clinical publications and sources relevant to this clinical criteria Note: Click the hyperlink to navigate directly to that section. March 29, 2019 Copyright © 2019 Health Information Designs, LLC 1 Horizant -

Métrologie De La Douleur Animale Sur Modèles Expérimentaux : Développement Et Validation De Biomarqueurs Neuroprotéomiques

Université de Montréal Métrologie de la douleur animale sur modèles expérimentaux : développement et validation de biomarqueurs neuroprotéomiques. par Colombe Otis Département de biomédecine vétérinaire Faculté de médecine vétérinaire Thèse présentée à la Faculté de médecine vétérinaire en vue de l’obtention du grade de philosophiæ doctor (Ph. D.) en sciences vétérinaires option pharmacologie Août, 2017 © Colombe Otis, 2017 Résumé La douleur est un phénomène complexe et dynamique comprenant un processus primaire et sensoriel, la nociception, auquel se rajoutent des réactions de défense et d'alarme psychophysiologiques. Ceci conduit au développement d'une véritable mémoire de la douleur, individuelle et modulée (plasticité neuronale) par des expériences précédentes de douleur, incluant entre autres, des phénomènes de sensibilisation nociceptive. Pour bien comprendre les mécanismes de sensibilisation centrale, les modèles animaux mimant les pathologies humaines sont d’une importance primordi ale. Or, pour ce faire, nous avons proposé une série d'approches expérimentales translationnelles par le développement de modèles expérimentaux de douleur bovine, canine et murine afin de caractériser les atteintes du protéome spinal en fonction du niveau de douleur perçu par l'animal et d’identifier le (les) marqueur (s) potentiellement modulé (s) par la sensibilisation nociceptive. À l’aide de la neuroprotéomique, nous avons identifié sur un modèle bovin de douleur viscérale, la protéine transthyrétine (TTR) comme étant sous-exprimée dans le protéome spinal en présence de douleur et ce, vérifié également dans le modèle canin de douleur chronique liée à l’arthrose chirurgicale. Ces résultats suggèrent la possibilité d’entrevoir la TTR comme un biomarqueur potentiel de la douleur chronique. Notre découverte de la relation entre les niveaux spinaux de TTR par neuroprotéomique et l’ hypersensibilité à la douleur dans les modèles bovin et canin soutiennent l’implication de composantes inflammatoires nociceptives et immunitaires. -

Big Pain Assays Aren't a Big Pain with the Raptor Biphenyl LC Column

Featured Application: 231 Pain Management and Drugs of Abuse Compounds in under 10 Minutes by LC-MS/MS Big Pain Assays Aren’t a Big Pain with the Raptor Biphenyl LC Column • 231 compounds, 40+ isobars, 10 drug classes, 22 ESI- compounds in 10 minutes with 1 column. • A Raptor SPP LC column with time-tested Restek Biphenyl selectivity is the most versatile, multiclass-capable LC column available. • Achieve excellent separation of critical isobars with no tailing peaks. • Run fast and reliable high-throughput LC-MS/MS analyses with increased sensitivity using simple mobile phases. The use of pain management drugs is steadily increasing. As a result, hospital and reference labs are seeing an increase in patient samples that must be screened for a wide variety of pain management drugs to prevent drug abuse and to ensure patient safety and adherence to their medication regimen. Thera- peutic drug monitoring can be challenging due to the low cutoff levels, potential matrix interferences, and isobaric drug compounds. To address these chal- lenges, many drug testing facilities are turning to liquid chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) for its increased speed, sensitivity, and specificity. As shown in the analysis below, Restek’s Raptor Biphenyl column is ideal for developing successful LC-MS/MS pain medication screening methodologies. With its exceptionally high retention and unique selectivity, 231 multiclass drug compounds and metabolites—including over 40 isobars—can be analyzed in just 10 minutes. In addition, separate panels have been optimized on the Raptor Biphenyl column specifically for opioids, antianxiety drugs, barbiturates, NSAIDs and analgesics, antidepressants, antiepileptics, antipsychotics, hallucinogens, and stimulants for use during confirmation and quantitative analyses. -

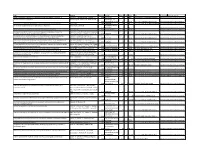

Preventive Report Appendix

Title Authors Published Journal Volume Issue Pages DOI Final Status Exclusion Reason Nasal sumatriptan is effective in treatment of migraine attacks in children: A Ahonen K.; Hamalainen ML.; Rantala H.; 2004 Neurology 62 6 883-7 10.1212/01.wnl.0000115105.05966.a7 Deemed irrelevant in initial screening Seasonal variation in migraine. Alstadhaug KB.; Salvesen R.; Bekkelund SI. Cephalalgia : an 2005 international journal 25 10 811-6 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2005.01018.x Deemed irrelevant in initial screening Flunarizine, a calcium channel blocker: a new prophylactic drug in migraine. Amery WK. 1983 Headache 23 2 70-4 10.1111/j.1526-4610.1983.hed2302070 Deemed irrelevant in initial screening Monoamine oxidase inhibitors in the control of migraine. Anthony M.; Lance JW. Proceedings of the 1970 Australian 7 45-7 Deemed irrelevant in initial screening Prostaglandins and prostaglandin receptor antagonism in migraine. Antonova M. 2013 Danish medical 60 5 B4635 Deemed irrelevant in initial screening Divalproex extended-release in adolescent migraine prophylaxis: results of a Apostol G.; Cady RK.; Laforet GA.; Robieson randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. WZ.; Olson E.; Abi-Saab WM.; Saltarelli M. 2008 Headache 48 7 1012-25 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2008.01081.x Deemed irrelevant in initial screening Divalproex sodium extended-release for the prophylaxis of migraine headache in Apostol G.; Lewis DW.; Laforet GA.; adolescents: results of a stand-alone, long-term open-label safety study. Robieson WZ.; Fugate JM.; Abi-Saab WM.; 2009 Headache 49 1 45-53 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2008.01279.x Deemed irrelevant in initial screening Safety and tolerability of divalproex sodium extended-release in the prophylaxis of Apostol G.; Pakalnis A.; Laforet GA.; migraine headaches: results of an open-label extension trial in adolescents. -

Chapter 25 Mechanisms of Action of Antiepileptic Drugs

Chapter 25 Mechanisms of action of antiepileptic drugs GRAEME J. SILLS Department of Molecular and Clinical Pharmacology, University of Liverpool _________________________________________________________________________ Introduction The serendipitous discovery of the anticonvulsant properties of phenobarbital in 1912 marked the foundation of the modern pharmacotherapy of epilepsy. The subsequent 70 years saw the introduction of phenytoin, ethosuximide, carbamazepine, sodium valproate and a range of benzodiazepines. Collectively, these compounds have come to be regarded as the ‘established’ antiepileptic drugs (AEDs). A concerted period of development of drugs for epilepsy throughout the 1980s and 1990s has resulted (to date) in 16 new agents being licensed as add-on treatment for difficult-to-control adult and/or paediatric epilepsy, with some becoming available as monotherapy for newly diagnosed patients. Together, these have become known as the ‘modern’ AEDs. Throughout this period of unprecedented drug development, there have also been considerable advances in our understanding of how antiepileptic agents exert their effects at the cellular level. AEDs are neither preventive nor curative and are employed solely as a means of controlling symptoms (i.e. suppression of seizures). Recurrent seizure activity is the manifestation of an intermittent and excessive hyperexcitability of the nervous system and, while the pharmacological minutiae of currently marketed AEDs remain to be completely unravelled, these agents essentially redress the balance between neuronal excitation and inhibition. Three major classes of mechanism are recognised: modulation of voltage-gated ion channels; enhancement of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA)-mediated inhibitory neurotransmission; and attenuation of glutamate-mediated excitatory neurotransmission. The principal pharmacological targets of currently available AEDs are highlighted in Table 1 and discussed further below. -

Lyrica Gabapentin: an Easy Switch!

Pharmacist Contacts: [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected] Lyrica Gabapentin: An Easy Switch! Conversion between Lyrica and gabapentin is generally Daily Dose of Daily Dose of Shingrix well tolerated and direct switching minimizes potential for Gabapentin Lyrica Reactogenicity gaps in pain relief. In the absence of seizure history, the (mg/day) (mg/day) drugs can be directly interchanged; patients can be advised 0 – 300 50 to discontinue Lyrica and begin gabapentin the following When giving Shingrix, day. Patients with a seizure history should be cross-tapered 301 – 450 75 counsel patients about over 1 – 4 weeks. 451 – 600 100 expected reactions. 601 – 900 150 While cross-tolerance is expected, patients should be 901 – 1200 200 advised adverse effects such as drowsiness or edema may There is a 10% chance of 1201 – 1500 250 still emerge when therapy is changed but tend to decrease developing a grade 3 1501 – 1800 300 injection site reaction with time. A conservative approach may be useful to 1801 – 2100 350 and/or systemic mitigate adverse effects. reactions (see table 2101 – 2400 400 Titration of gabapentin to the maximum tolerated 2401 – 2700 450 below) – these symptoms therapeutic dose is important. The therapeutic dosing 2701 – 3000 500 were significant enough range in neuropathic pain trials is 1800-3600 mg/day to prevent regular (normal renal function). The pharmacokinetics of 3001 – 3600 600 activities in about 17% of gabapentin require regular dosing, it will not work if clinical trial patients, but dosed “as needed.” Studies show minimal benefit & tend to pass within 2-3 more adverse effects when high days. -

Conjugation of Tryptamine to Biologically Active Carboxylic Acids in Order to Create Prodrugs

ISSN 2380-5064 | The Arsenal is published by the Augusta University Libraries | http://guides.augusta.edu/arsenal Volume 4, Issue 1 (2021) Special Edition Issue CONJUGATION OF TRYPTAMINE TO BIOLOGICALLY ACTIVE CARBOXYLIC ACIDS IN ORDER TO CREATE PRODRUGS Colin Miller, Jr. and Iryna O. Lebedyeva Citation Miller, C., Jr., & Lebedyeva, I. O. (2021). Conjugation of tryptamine to biologically active carboxylic acids in order to create prodrugs. The Arsenal: The Undergraduate Research Journal of Augusta University, 4(1), 26. http://doi.org/10.21633/issn.2380.5064/s.2021.04.01.26 © Miller, Jr. and Lebedyeva 2021. This open access article is distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.0/). Conjugation of Tryptamine to Biologically Active Carboxylic Acids in Order to Create Prodrugs Presenter(s): Colin Miller, Jr. Author(s): Colin Miller Jr. and Iryna O. Lebedyeva Faculty Sponsor(s): Iryna O. Lebedyeva, PhD Affiliation(s): Department of Chemistry and Physics (Augusta Univ.) ABSTRACT A number of blood and brain barrier penetrating neurotransmitters contain polar functional groups. Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) is an amino acid, which is one of the primary inhibitory neurotransmitter in the brain and a major inhibitory neurotransmitter in the spinal cord. Antiepileptic medications such as Gabapentin, Phenibut, and Pregabalin have been developed to structurally represent GABA. These drugs are usually prescribed for the treatment of neuropathic pain. Since these drugs contain a polar carboxylic acid group, it affects their ability to penetrate the blood and brain barrier. To address the low bioavailability and tendency for intramolecular cyclization of Gabapentin, its less polar prodrug Gabapentin Enacarbil has been approved in 2011. -

(12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 8,283,487 B2 Ben Moha-Lerman Et Al

USOO8283487B2 (12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 8,283,487 B2 Ben Moha-Lerman et al. (45) Date of Patent: Oct. 9, 2012 (54) PROCESSES FOR THE PREPARATION AND 2003/0176398 A1 9/2003 Gallop et al. PURIFICATION OF GABAPENTIN 2004/0077553 A1* 4/2004 Gallop et al. ................... 514, 19 2005/O154057 A1 7/2005 Estrada et al. ENACARBL 2007/0049627 A1 3, 2007 Tran (75) Inventors: Elena Ben Moha-Lerman, Kiryat Ono FOREIGN PATENT DOCUMENTS (IL); Tamar Nidam, Yehud (IL); Meital WO WO O2/10O347 12/2002 Cohen, Petach-Tikva (IL); Sharon WO WO 2005/0377.84 4/2005 Avhar-Maydan, Givataym (IL); Anna Balanov, Rehovot (IL) OTHER PUBLICATIONS X. Yuan et al. “In Situ Preparation of Zinc Salts of Unsaturated (73) Assignee: Teva Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd., Carboxylic Acids to Reinforce NBR' J. Applied Polymer Science, Petach-Tikva (IL) vol. 77, p. 2740-2748 (2000). - r J. Alexander et al. “(Acyloxy)alkyl Carbamates as Novel Biorevers (*) Notice: Subject to any disclaimer, the term of this ible Prodrugs for Amines: Increased Permeation through Biological patent is extended or adjusted under 35 Membranes”.J. Med. Chem. 1988, 31, pp. 318-322. U.S.C. 154(b) by 249 days. S.M. Rahmathullah et al. “Prodrugs for Amidines: Synthesis and Anti-Pneumocystis carinii Activity of Carbamates of 2.5-Bis(4- (21) Appl. No.: 12/626,682 amidinophenyl)furan” J. Med. Chem. 1999, 42, pp. 3994-4000. (22) Filed: Nov. 26, 2009 * cited by examiner (65) Prior Publication Data Primary Examiner — Joseph K. McKane US 2010/O160665 A1 Jun. 24, 2010 Assistant Examiner — Alicia L Otton (74) Attorney, Agent, or Firm — Arent Fox LLP Related U.S. -

Comparing Adverse Effects of Analgesic Strategies For

Comparing Adverse Effects daily and weekly time during which higher than that of the only ATC opi- their pain interfered with their mood oids group and 17 times higher than of Analgesic Strategies for or activities, and they indicated the that of the only PRN opioids group. Chronic Cancer Pain amount of relief they received from Source: J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;33(1):67–77. their pain medicine in the previ- Nausea, vomiting, drowsiness, lack ous week. They also completed the of energy, urinary retention—some- Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS), Clopidogrel: Best Results times the adverse effects of the anal- which measures patients’ ability to per- Pre- or Post-PCI? gesic medication are enough to derail form activities of daily living and their pain management for patients with need for caregiver assistance. When is the best time to give the anti- cancer. It would help to understand There were no significant differ- platelet clopidogrel to patients sched- the relationships between the type of ences between any of the four groups uled for diagnostic coronary angiogra- analgesic prescription and the preva- in terms of pain intensity or amount of phy—before ad hoc coronary stenting lence and severity of adverse effects. time spent in pain. Total pain interfer- or immediately after? Researchers from But not much information is available, ence scores, however, were significantly University of Debrecen, Debrecen, say researchers from the University higher in the ATC plus PRN opioids Hungary and Medical University of of California, San Francisco; the Uni- group than in the no opioids group. Vienna and Wilhelminenhospital, both versity of Nebraska, Omaha; and the The ATC plus PRN opioids group in Vienna, Austria say starting treat- University of Texas Southwestern Med- also had significantly lower functional ment before percutaneous coronary ical Center, Dallas. -

More Treatments on Deck for Alcohol Use Disorder

News & Analysis Medical News & Perspectives More Treatments on Deck for Alcohol Use Disorder Jeff Lyon hirteen years have passed since the Raye Z. Litten, PhD, acting director of the ment for AUD were actually prescribed an US Food and Drug Administration NIAAA’s Division of Medications Develop- AUD medication. T (FDA) last approved a new medica- ment and principal investigator of the trial, It is a complicated problem, says John tion to help the nation’s millions of people says the agency is “excited.” Rotrosen, MD, a psychiatrist and addiction withalcoholusedisorder(AUD)stopormod- Nevertheless, the science of alcohol ad- specialist at New York University School of erate their drinking. diction has seen its share of medicines that Medicine. “To a large extent primary care Only 3 such formulations exist, and 1, failed to live up to their early promise dur- physicians don’t screen for alcoholism,” he disulfiram, dates to the Prohibition era. ing full-scale testing. So Litten said the said. “When they do, they may note it, but Known commercially as Antabuse and agency isn’t putting all its eggs in one bas- don’t really do anything about it.” introduced in 1923, it makes people memo- ket. “You need as many weapons as pos- As far as the failure to prescribe exist- rably ill if they ingest alcohol, but it doesn’t sible to treat a complex disease like alcohol ing medications for AUD, Rotrosen blames stop the cravings. The other 2, naltrexone use disorder,” he said. a lack of knowledge. “A lot of doctors in and acamprosate, approved in 1994 and But therein lies a second difficulty. -

Gabapentin Abuse Gabapentin (Neurontin®) Is Indicated for the Treatment of Epilepsy and Neuro- Pathic Pain, Including Post-Herpetic Neuralgia

November 2018 Poison Center Hotline: 1-800-222-1222 The Maryland Poison Center’s Monthly Update: News, Advances, Information Gabapentin Abuse Gabapentin (Neurontin®) is indicated for the treatment of epilepsy and neuro- pathic pain, including post-herpetic neuralgia. Gabapentin is often prescribed off -label for a variety of conditions including insomnia, anxiety, bipolar disorder, migraines, drug and alcohol addiction, and others. Off-label use exceeds use for FDA approved indications. Termed a gabapentinoid, it is an analog of γ- aminobutyric acid (GABA) that increases GABA but does not bind to GABA re- ceptors. It has a selective inhibitory effect on voltage-gated calcium channels containing the α2δ1 subunit. Its exact mechanism for epilepsy and pain is un- clear. Gabapentin is not a controlled substance as it was believed that gabapentin had no abuse potential when approved by the FDA in 1993. Overall, if used at thera- Did you know? peutic doses by patients without a substance abuse/misuse history, the risk of misuse is probably lower than that of other drugs such as benzodiazepines. There are reports of abuse of However, reports are increasing of gabapentin misuse and abuse. Motivations pregabalin (Lyrica ®), another for misuse include recreational use, mood and/or anxiety control, potentiating gabapentinoid used for the effects of drug abuse treatment, pain management, reducing cravings for neuropathic pain, post-herpetic other drugs, managing withdrawal from other drugs, substituting for other pain and fibromyalgia. drugs, and gabapentin addiction (Addiction 2016;11:1160-74). The risk of misuse Approved by the FDA in 2004, increases in people with a history of recreational drug abuse who take gabapen- pregabalin is Schedule V. -

Membrane Stabilizer Medications in the Treatment of Chronic Neuropathic Pain: a Comprehensive Review

Current Pain and Headache Reports (2019) 23: 37 https://doi.org/10.1007/s11916-019-0774-0 OTHER PAIN (A KAYE AND N VADIVELU, SECTION EDITORS) Membrane Stabilizer Medications in the Treatment of Chronic Neuropathic Pain: a Comprehensive Review Omar Viswanath1,2,3 & Ivan Urits4 & Mark R. Jones4 & Jacqueline M. Peck5 & Justin Kochanski6 & Morgan Hasegawa6 & Best Anyama7 & Alan D. Kaye7 Published online: 1 May 2019 # Springer Science+Business Media, LLC, part of Springer Nature 2019 Abstract Purpose of Review Neuropathic pain is often debilitating, severely limiting the daily lives of patients who are affected. Typically, neuropathic pain is difficult to manage and, as a result, leads to progression into a chronic condition that is, in many instances, refractory to medical management. Recent Findings Gabapentinoids, belonging to the calcium channel blocking class of drugs, have shown good efficacy in the management of chronic pain and are thus commonly utilized as first-line therapy. Various sodium channel blocking drugs, belonging to the categories of anticonvulsants and local anesthetics, have demonstrated varying degrees of efficacy in the in the treatment of neurogenic pain. Summary Though there is limited medical literature as to efficacy of any one drug, individualized multimodal therapy can provide significant analgesia to patients with chronic neuropathic pain. Keywords Neuropathic pain . Chronic pain . Ion Channel blockers . Anticonvulsants . Membrane stabilizers Introduction Neuropathic pain, which is a result of nervous system injury or lives of patients who are affected. Frequently, it is difficult to dysfunction, is often debilitating, severely limiting the daily manage and as a result leads to the progression of a chronic condition that is, in many instances, refractory to medical This article is part of the Topical Collection on Other Pain management.