Arxiv:1702.03516V4 [Math.NT] 17 Mar 2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Life Inspired by an Unexpected Genius

Quanta Magazine A Life Inspired by an Unexpected Genius The mathematician Ken Ono believes that the story of Srinivasa Ramanujan — mathematical savant and two-time college dropout — holds valuable lessons for how we find and reward hidden genius. By John Pavlus The mathematician Ken Ono in his office at Emory University in Atlanta. For the first 27 years of his life, the mathematician Ken Ono was a screw-up, a disappointment and a failure. At least, that’s how he saw himself. The youngest son of first-generation Japanese immigrants to the United States, Ono grew up under relentless pressure to achieve academically. His parents set an unusually high bar. Ono’s father, an eminent mathematician who accepted an invitation from J. Robert Oppenheimer to join the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, N.J., expected his son to follow in his footsteps. Ono’s mother, meanwhile, was a quintessential “tiger parent,” discouraging any interests unrelated to the steady accumulation of scholarly credentials. This intellectual crucible produced the desired results — Ono studied mathematics and launched a promising academic career — but at great emotional cost. As a teenager, Ono became so desperate https://www.quantamagazine.org/the-mathematician-ken-onos-life-inspired-by-ramanujan-20160519/ May 19, 2016 Quanta Magazine to escape his parents’ expectations that he dropped out of high school. He later earned admission to the University of Chicago but had an apathetic attitude toward his studies, preferring to party with his fraternity brothers. He eventually discovered a genuine enthusiasm for mathematics, became a professor, and started a family, but fear of failure still weighed so heavily on Ono that he attempted suicide while attending an academic conference. -

![Arxiv:1906.07410V4 [Math.NT] 29 Sep 2020 Ainlpwrof Power Rational Ftetidodrmc Ht Function Theta Mock Applications](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9806/arxiv-1906-07410v4-math-nt-29-sep-2020-ainlpwrof-power-rational-ftetidodrmc-ht-function-theta-mock-applications-459806.webp)

Arxiv:1906.07410V4 [Math.NT] 29 Sep 2020 Ainlpwrof Power Rational Ftetidodrmc Ht Function Theta Mock Applications

MOCK MODULAR EISENSTEIN SERIES WITH NEBENTYPUS MICHAEL H. MERTENS, KEN ONO, AND LARRY ROLEN In celebration of Bruce Berndt’s 80th birthday Abstract. By the theory of Eisenstein series, generating functions of various divisor functions arise as modular forms. It is natural to ask whether further divisor functions arise systematically in the theory of mock modular forms. We establish, using the method of Zagier and Zwegers on holomorphic projection, that this is indeed the case for certain (twisted) “small divisors” summatory functions sm σψ (n). More precisely, in terms of the weight 2 quasimodular Eisenstein series E2(τ) and a generic Shimura theta function θψ(τ), we show that there is a constant αψ for which ∞ E + · E2(τ) 1 sm n ψ (τ) := αψ + X σψ (n)q θψ(τ) θψ(τ) n=1 is a half integral weight (polar) mock modular form. These include generating functions for combinato- rial objects such as the Andrews spt-function and the “consecutive parts” partition function. Finally, in analogy with Serre’s result that the weight 2 Eisenstein series is a p-adic modular form, we show that these forms possess canonical congruences with modular forms. 1. Introduction and statement of results In the theory of mock theta functions and its applications to combinatorics as developed by Andrews, Hickerson, Watson, and many others, various formulas for q-series representations have played an important role. For instance, the generating function R(ζ; q) for partitions organized by their ranks is given by: n n n2 n (3 +1) m n q 1 ζ ( 1) q 2 R(ζ; q) := N(m,n)ζ q = −1 = − − n , (ζq; q)n(ζ q; q)n (q; q)∞ 1 ζq n≥0 n≥0 n∈Z − mX∈Z X X where N(m,n) is the number of partitions of n of rank m and (a; q) := n−1(1 aqj) is the usual n j=0 − q-Pochhammer symbol. -

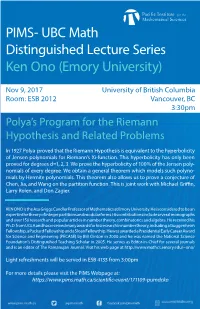

UBC Math Distinguished Lecture Series Ken Ono (Emory University)

PIMS- UBC Math Distinguished Lecture Series Ken Ono (Emory University) Nov 9, 2017 University of British Columbia Room: ESB 2012 Vancouver, BC 3:30pm Polya’s Program for the Riemann Hypothesis and Related Problems In 1927 Polya proved that the Riemann Hypothesis is equivalent to the hyperbolicity of Jensen polynomials for Riemann’s Xi-function. This hyperbolicity has only been proved for degrees d=1, 2, 3. We prove the hyperbolicity of 100% of the Jensen poly- nomials of every degree. We obtain a general theorem which models such polyno- mials by Hermite polynomials. This theorem also allows us to prove a conjecture of Chen, Jia, and Wang on the partition function. This is joint work with Michael Griffin, Larry Rolen, and Don Zagier. KEN ONO is the Asa Griggs Candler Professor of Mathematics at Emory University. He is considered to be an expert in the theory of integer partitions and modular forms. His contributions include several monographs and over 150 research and popular articles in number theory, combinatorics and algebra. He received his Ph.D. from UCLA and has received many awards for his research in number theory, including a Guggenheim Fellowship, a Packard Fellowship and a Sloan Fellowship. He was awarded a Presidential Early Career Award for Science and Engineering (PECASE) by Bill Clinton in 2000 and he was named the National Science Foundation’s Distinguished Teaching Scholar in 2005. He serves as Editor-in-Chief for several journals and is an editor of The Ramanujan Journal. Visit his web page at http://www.mathcs.emory.edu/~ono/ Light refreshments will be served in ESB 4133 from 3:00pm For more details please visit the PIMS Webpage at: https://www.pims.math.ca/scientific-event/171109-pumdcko www.pims.math.ca @pimsmath facebook.com/pimsmath . -

CM Values and Fourier Coefficients of Harmonic Maass Forms

CM values and Fourier coefficients of harmonic Maass forms Vom Fachbereich Mathematik der Technischen Universit¨at Darmstadt zur Erlangung des Grades eines Doktors der Naturwissenschaften (Dr. rer. nat.) genehmigte Dissertation von Dipl.-Math. Claudia Alfes aus Dorsten Referent: Prof. Dr. J. H. Bruinier 1. Korreferent: Prof. Ken Ono, PhD 2. Korreferent: Prof. Dr. Nils Scheithauer Tag der Einreichung: 11. Dezember 2014 Tag der mundlichen¨ Prufung:¨ 5. Februar 2015 Darmstadt 2015 D 17 ii Danksagung Hiermit m¨ochte ich allen danken, die mich w¨ahrend meines Studiums und meiner Promotion, in- und außerhalb der Universit¨at, unterstutzt¨ und begleitet haben. Ein besonders großer Dank geht an meinen Doktorvater Professor Dr. Jan Hendrik Bruinier, der mir die Anregung fur¨ das Thema der Arbeit gegeben und mich stets gefordert, gef¨ordert und motiviert hat. Außerdem danke ich Professor Ken Ono, der mich ebenfalls auf viele interessante Fragestellungen aufmerksam gemacht hat und mir stets mit Rat und Tat zur Seite stand. Vielen Dank auch an Professor Nils Scheithauer fur¨ interessante Hinweise und fur¨ die Bereitschaft, die Arbeit zu begutachten. Ein weiteres großes Dankesch¨on geht an Dr. Stephan Ehlen, von ihm habe ich viel gelernt und insbesondere große Hilfe bei den in Sage angefertigten Rechnungen erhalten. Vielen Dank auch an Anna von Pippich fur¨ viele hilfreiche Hinweise. Weiterer Dank geht an die fleißigen Korrekturleser Yingkun Li, Sebastian Opitz, Stefan Schmid und Markus Schwagenscheidt die viel Zeit investiert haben, viele nutzliche¨ Anmerkungen hatten und zahlreiche Tippfehler gefunden haben. Daruber¨ hinaus danke ich der Deutschen Forschungsgemeinschaft, aus deren Mitteln meine Stelle an der Technischen Universit¨at Darmstadt zu Teilen im Rahmen des Projektes Schwache Maaß-Formen" und der Forschergruppe Symmetrie, Geometrie und " " Arithmetik" finanziert wurde. -

Sixth Ramanujan Colloquium

University of Florida, Mathematics Department SIXTH RAMANUJAN* COLLOQUIUM by Professor Ken Ono ** Emory University on Adding and Counting Date and Time: 4:05 - 4:55pm, Monday, March 12, 2012 Room: LIT 109 Refreshments: After Colloquium in the Atrium (LIT 339) Abstract: One easily sees that 4 = 3+1 = 2+2 = 2+1+1 = 1+1+1+1, and so we say there are five partitions of 4. What may come as a surprise is that this simple task leads to very subtle and difficult problems in mathematics. The nature of adding and counting has fascinated many of the world's leading mathematicians: Euler, Ramanujan, Hardy, Rademacher, Dyson, to name a few. And as is typical in number theory, some of the most fundamental (and simple to state) questions have remained open. In 2010, with the support of the American Institute for Mathematics and the National Science Foundation, the speaker assembled an international team of researchers to attack some of these problems. Come hear about their findings: new theories which solve some of the famous old questions. * ABOUT RAMANUJAN: Srinivasa Ramanujan (1887-1920), a self-taught genius from South India, dazzled mathematicians at Cambridge University by communicating bewildering formulae in a series of letters. G. H. Hardy invited Ramanujan to work with him at Cambridge, convinced that Ramanujan was a "Newton of the East"! Ramanujan's work has had a profound and wide impact within and outside mathematics. He is considered one of the greatest mathematicians in history. ** ABOUT THE SPEAKER: Ken Ono is one of the top number theorists in the world and a leading authority in the theory of partitions, modular forms, and the work of the Indian genius Srinivasa Ramanujan. -

Mentoring Graduate Students: Some Personal Thoughts3

Early Career the listeners. Like a toddler. He said he tested this when I am not quite sure how I successfully navigated the he was a PhD student. He wanted to know what “ho- stormy seas that defined my early career in mathematics. lomorphic vector bundle” means. So, he went to the What I do know is that I am now fifty-one years old, and math lounge and repeated those three words over and I have enjoyed a privileged career as a research mathe- over again. Now he is an expert in complex geometry. matician. I have had the pleasure of advising thirty PhD • Waking up to Email. Every mentor has a different style. students, with most assuming postdoctoral positions at So does every mentee. A while back, PhD students at top Group 1 institutions. Furthermore, I am proud of the Berkeley complained that they do not get enough at- fact that mathematics continues to play a central role in tention from their advisors. My students think that they their daily lives. receive too much attention from their advisor. A friend How did I make it? Good question. I do know that I once referred to my style as “the samurai method.” It needed the strong support of mentors who kept me afloat involves a barrage of emails, usually sent between 4am along the way. You might know their names: Paul Sally, and 5am. While this is fine for some, it does not work Basil Gordon, and Andrew Granville. I learned a lot from for others. these teachers, and I hope that I have been able to pass their wisdom on to my students of all ages. -

Harmonic Maass Forms, Mock Modular Forms, and Quantum Modular Forms

HARMONIC MAASS FORMS, MOCK MODULAR FORMS, AND QUANTUM MODULAR FORMS KEN ONO Abstract. This short course is an introduction to the theory of harmonic Maass forms, mock modular forms, and quantum modular forms. These objects have many applications: black holes, Donaldson invariants, partitions and q-series, modular forms, probability theory, singular moduli, Borcherds products, central values and derivatives of modular L-functions, generalized Gross-Zagier formulae, to name a few. Here we discuss the essential facts in the theory, and consider some applications in number theory. This mathematics has an unlikely beginning: the mystery of Ramanujan’s enigmatic “last letter” to Hardy written three months before his untimely death. Section 15 gives examples of projects which arise naturally from the mathematics described here. Modular forms are key objects in modern mathematics. Indeed, modular forms play cru- cial roles in algebraic number theory, algebraic topology, arithmetic geometry, combinatorics, number theory, representation theory, and mathematical physics. The recent history of the subject includes (to name a few) great successes on the Birch and Swinnerton-Dyer Con- jecture, Mirror Symmetry, Monstrous Moonshine, and the proof of Fermat’s Last Theorem. These celebrated works are dramatic examples of the evolution of mathematics. Here we tell a different story, the mathematics of harmonic Maass forms, mock modular forms, and quantum modular forms. This story has an unlikely beginning, the mysterious last letter of the Ramanujan. 1. Ramanujan The story begins with the legend of Ramanujan, the amateur Indian genius who discovered formulas and identities without any rigorous training1 in mathematics. He recorded his findings in mysterious notebooks without providing any indication of proofs. -

Contemporary Mathematics 291

CONTEMPORARY MATHEMATICS 291 q-Series with Applications to Combinatorics, Number Theory, and Physics A Conference on q-Series with Applications to Combinatorics, Number Theory, and Physics October 26-28, 2000 University of Illinois Bruce C. Berndt Ken Ono Editors http://dx.doi.org/10.1090/conm/291 Selected Titles in This Series 291 Bruce C. Berndt and Ken Ono, Editors, q-Series with applications to combinatorics, number theory, and physics, 2001 290 Michel L. Lapidus and Machiel van Frankenhuysen, Editors, Dynamical, spectral, and arithmetic zeta functions, 2001 289 Salvador Perez-Esteva and Carlos Villegas-Blas, Editors, Second summer school in analysis and mathematical physics: Topics in analysis: Harmonic, complex, nonlinear and quantization, 2001 288 Marisa Fernandez and Joseph A. Wolf, Editors, Global differential geometry: The mathematical legacy of Alfred Gray, 2001 287 Marlos A. G. Viana and Donald St. P. Richards, Editors, Algebraic methods in statistics and probability, 2001 286 Edward L. Green, Serkan Ho§ten, Reinhard C. Laubenbacher, and Victoria Ann Powers, Editors, Symbolic computation: Solving equations in algebra, geometry, and engineering, 2001 285 Joshua A. Leslie and Thierry P. Robart, Editors, The geometrical study of differential equations, 2001 284 Gaston M. N'Guerekata and Asamoah Nkwanta, Editors, Council for African American researchers in the mathematical sciences: Volume IV, 2001 283 Paul A. Milewski, Leslie M. Smith, Fabian Waleffe, and Esteban G. Tabak, Editors, Advances in wave interaction and turbulence, -

Mathematisches Forschungsinstitut Oberwolfach Modular Forms

Mathematisches Forschungsinstitut Oberwolfach Report No. 22/2014 DOI: 10.4171/OWR/2014/22 Modular Forms Organised by Jan Hendrik Bruinier, Darmstadt Atsushi Ichino, Kyoto Tamotsu Ikeda, Kyoto Ozlem¨ Imamoglu, Z¨urich 27 April – 3 May 2014 Abstract. The theory of Modular Forms has been central in mathematics with a rich history and connections to many other areas of mathematics. The workshop explored recent developments and future directions with a particular focus on connections to the theory of periods. Mathematics Subject Classification (2010): 11xx. Introduction by the Organisers The workshop Modular Forms, organized by Jan Hendrik Bruinier (Darmstadt), Atsushi Ichino (Kyoto), Tamotsu Ikeda (Kyoto) and Ozlem¨ Imamoglu (Z¨urich) consisted of 19 one-hour long lectures and covered various recent developments in the theory of modular and automorphic forms and related fields. A particular focus was on the connection of modular forms to periods, since there have been important developments in that direction in recent years. In this context, the topics that the workshop addressed include the global Gross- Prasad conjecture and its analogs, which predict a relationship between periods of automorphic forms and central values of L-functions, the theory of liftings and their applications to period relations, as well as explicit aspects of these formulas and relations with a view towards the arithmetic properties of periods. There are two fundamental ways in which automorphic forms are related to periods. First, according to the conjectures of Deligne, Beilinson and Scholl, spe- cial values of motivic automorphic L-functions at integral arguments should be given by periods and encode important arithmetic information, such as ranks of 1222 Oberwolfach Report 22/2014 Chow groups and Selmer groups. -

Vitae Ken Ono Citizenship

Vitae Ken Ono Citizenship: USA Date of Birth: March 20,1968 Place of Birth: Philadelphia, Pennsylvania Education: • Ph.D., Pure Mathematics, University of California at Los Angeles, March 1993 Thesis Title: Congruences on the Fourier coefficients of modular forms on Γ0(N) with number theoretic applications • M.A., Pure Mathematics, University of California at Los Angeles, March 1990 • B.A., Pure Mathematics, University of Chicago, June 1989 Research Interests: • Automorphic and Modular Forms • Algebraic Number Theory • Theory of Partitions with applications to Representation Theory • Elliptic curves • Combinatorics Publications: 1. Shimura sums related to quadratic imaginary fields Proceedings of the Japan Academy of Sciences, 70 (A), No. 5, 1994, pages 146-151. 2. Congruences on the Fourier coefficeints of modular forms on Γ0(N), Contemporary Mathematics 166, 1994, pages 93-105., The Rademacher Legacy to Mathe- matics. 3. On the positivity of the number of partitions that are t-cores, Acta Arithmetica 66, No. 3, 1994, pages 221-228. 4. Superlacunary cusp forms, (Co-author: Sinai Robins), Proceedings of the American Mathematical Society 123, No. 4, 1995, pages 1021-1029. 5. Parity of the partition function, 1 2 Electronic Research Annoucements of the American Mathematical Society, 1, No. 1, 1995, pages 35-42 6. On the representation of integers as sums of triangular numbers Aequationes Mathematica (Co-authors: Sinai Robins and Patrick Wahl) 50, 1995, pages 73-94. 7. A note on the number of t-core partitions The Rocky Mountain Journal of Mathematics 25, 3, 1995, pages 1165-1169. 8. A note on the Shimura correspondence and the Ramanujan τ(n)-function, Utilitas Mathematica 47, 1995, pages 153-160. -

![Arxiv:1911.05264V3 [Math.NT]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9272/arxiv-1911-05264v3-math-nt-3459272.webp)

Arxiv:1911.05264V3 [Math.NT]

A NOTE ON THE HIGHER ORDER TURAN´ INEQUALITIES FOR k-REGULAR PARTITIONS WILLIAM CRIAG AND ANNA PUN Abstract. Nicolas [8] and DeSalvo and Pak [3] proved that the partition function p(n) is log concave for n 25. Chen, Jia and Wang [2] proved that p(n) satisfies the third order ≥ Tur´an inequality, and that the associated degree 3 Jensen polynomials are hyperbolic for n 94. Recently, Griffin, Ono, Rolen and Zagier [5] proved more generally that for all d, ≥ the degree d Jensen polynomials associated to p(n) are hyperbolic for sufficiently large n. In this paper, we prove that the same result holds for the k-regular partition function pk(n) for k 2. In particular, for any positive integers d and k, the order d Tur´an ≥ inequalities hold for pk(n) for sufficiently large n. The case when d = k = 2 proves a conjecture by Neil Sloane that p2(n) is log concave. 1. Introduction and Statement of results The Tur´an inequality (or sometimes called Newton inequality) arises in the study of real entire functions in Laguerre-P´olya class, which is closely related to the study of the Riemann hypothesis [4, 12]. It is well known that the Riemann hypothesis is true if and only if the Riemann Xi function is in the Laguerre-P´olya class, where the Riemann Xi function is the entire order 1 function defined by 1 2 1 iz 1 iz 1 1 Ξ(z) := z π 2 − 4 Γ + ζ iz + . 2 − − 4 − 2 4 − 2 A necessary condition for the Riemann Xi function to be in the Laguerre-P´olya class is that the Maclaurin coefficients of the Xi function satisfy both the Tur´an and higher order Tur´an inequalities [4, 11]. -

Notes on Harmonic Maass Forms

HARMONIC MAASS FORMS AND MOCK MODULAR FORMS: OVERVIEW AND APPLICATIONS LARRY ROLEN Summer Research Institute on q-Series, Nankai University, July 2018. We have seen in Michael Mertens’ lectures that the “web of modularity” reverberates across many areas of mathematics and physics. In these lectures, we will discuss an extension of this web and its consequences and uses in different areas, and, in particular, in combinatorics and q-series. In fact, a lot of the best applications in the theory of harmonic Maass forms and motivating examples which historically motivated important results in our field have come from its interactions with these other subjects, in particular combinatorics and physics. For example, combinatorialists have a different set of tools and intuitions, and a knack for discovering interesting new examples of modular-type objects. Thus, collaboration and communication between the two areas, such as that established at this conference, is very fruitful in both directions. Before we begin, I have two brief comments. Firstly, a survey of many of the things in these notes and more generally the theory and applications of harmonic Maass forms can be found in the book on harmonic Maass forms by Bringmann, Folsom, Ono, and myself. Secondly, if you have any comments (or questions) about any of these notes, such as typos or general questions about the material, proofs, how to apply the techniques discussed here, etc., please feel free to email them to me. 1. History and motivation There are numerous beautiful examples of combinatorial generating functions which are both q- hypergeometric series and modular forms.